Key Takeaways

The U.S. Congress has until the end of 2025 to approve a new federal tax reform package before taxes for individuals and businesses go up on New Years Day 2026.

Many states follow the federal tax code in some way, which will create a cascade of changes to state tax codes if the 2017 tax law expires.

State lawmakers should consider proactively preserving expanded state level standard deductions to simplify tax filing and full expensing to expand business investment, which will provide certainty to individual and business taxpayers alike.

Should the Tax Cuts and Job Act expire at the end of the year, 80% of U.S. taxpayers will face a tax increase.

TCJA expiration would reduce wages by 0.5%, and reduce economic growth by 1.1% over ten years. The reduction in wages and economic activity would also reduce state income, business, and sales tax collections in future years.

Executive Summary: What Happens If the 2017 Tax Cuts Expire?

Unless Congress acts before January 1, 2026, the expiration of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will trigger widespread tax increases for 80% of Americans, significantly impact state economies, and disrupt state tax structures.

For federal taxes, the expiration of the 2017 TCJA would:

- Halve the federal standard deduction

- Reduce the federal child tax credit

- Reintroduce higher federal tax brackets

- Lower the federal estate tax threshold

- Eliminate key business tax benefits like federal Section 199A and full expensing

Altogether, individual and business taxes would rise by $500 billion annually, reducing U.S. GDP by 1.1% and wages by 0.5%.

TCJA Expiration Consequences for Taxpayers, Businesses, and State Governments

Since states benefited from TCJA-driven economic growth and tax base expansions, expiration means facing the opposite trends.

Reduced federal tax bases will shrink state tax bases, directly reducing state revenues, especially in states that automatically conform to federal definitions of income and deductions.

- Individual Income Tax Increases: Average taxpayer increases will vary by state. The highest amounts will fall to taxpayers in states like Massachusetts, Washington, and California.

- Shrinking Revenue: States with rolling conformity to federal law will see immediate changes, while “fixed conformity” states risk added complexity if Congress acts retroactively.

- Heavier Compliance Burdens: State tax codes tied to the federal standard deduction will be subject to automatic tax hikes unless they act to preserve the current higher deductions. Large standard deductions are one way to make filing taxes easier, because it reduces the need for many taxpayers to itemize their deductions.

- Increased Taxes on Small Business: The elimination of non-corporate business tax relief for pass-through entities in Section 199A and reduction of equipment expensing will hit small businesses, leading to reduced investment and growth.

- Increased International Business Taxes: The 2017 TCJA provided certainty for businesses with profits from international operations. If the law expires, changes to international tax rates will complicate state tax structures, particularly in states imposing the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) tax.

- Death Taxes Will Increase: A lower federal estate tax threshold would affect states like Connecticut that still align with federal estate tax law.

The 10 states that would be most affected by TCJA expiration

Though the effects of expiration would impact every state, the amount of average tax increase per filer, automatic state conformity to the federal tax code, loss of pro-growth business provisions like equipment expensing and pass through allowances, plus international business tax hikes, and increased state death tax mean some states have more to lose than others.

Recommendations for State Lawmakers:

- Proactively review their state’s tax conformity laws

- Preserve tax simplification measures like expanded standard deductions

- Make pro-growth policies like business expensing permanent

- Make contingency plans for revenue volatility if the 2017 tax cuts expire

- Advocate for federal tax stability with their federal congressional delegation

Introduction

Unless Congress acts, 80% of Americans will see a tax increase on January 1, 2026, with the expiration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017.

The standard deduction used by over 90% of taxpayers will be cut in half. The $2,000 child tax credit will fall to $1,000 and will be phased out for more taxpayers. Higher tax brackets will kick back in, as will a lower estate tax threshold.

On the business side, investment in new equipment will be literally taxed through reduced expensing, internationally-sourced income will face higher rates, and the Section 199A deduction used by 25 million small businesses will go away.

All told, taxes will increase by $500 billion a year, with an economic impact enough to reduce wages by 0.5% and Gross Domestic Product by 1.1%.

State governments will see major effects too, and contrary to the opinions of many TCJA opponents, those impacts will be highly detrimental. States benefited greatly from TCJA’s passage and resulting national economic growth and record state tax revenue growth. TCJA reduced federal tax revenue by $1.5 trillion over ten years, but this net figure included tax base expansions of $5.5 trillion (that most states conform to) and tax rate cuts of $4.0 trillion (that most states set independently of the federal government).

In other words, states structurally and mostly automatically adopted the federal provisions that expanded revenue and largely avoided those that did not. These trends will unfortunately work in reverse if TCJA expires, reducing state tax revenue. Some states, based on the design of their tax code or because of a higher dependence on high-income taxpayers, will be uniquely affected.

State policymakers have options, even if it remains uncertain exactly what Congress will do. Many states piggy-back on parallel provisions in the federal tax code to reduce complexity for taxpayers. But if the federal tax code is too uncertain, the benefits of this “conformity” are reduced. States should keep a key simplification feature (the doubled standard deduction) and a key pro-growth feature (business full expensing) whether Congress acts by the end of the year or not.

There is precedent: most states had conditional laws in their tax codes to revive the now-defunct state estate “pick-up” tax only if Congress failed to extend the Bush tax cuts in 2010. States could now evaluate their conformity laws and ranges of revenue effects resulting from congressional action or inaction, and communicate the importance of federal tax code certainty to their counterparts in Washington, DC.

Upon TCJA Expiration, 80% Of U.S. Taxpayers Will Face A Tax Increase

Average tax increase per filer from TCJA expiration by state

Source: Calculations by the Tax Foundation

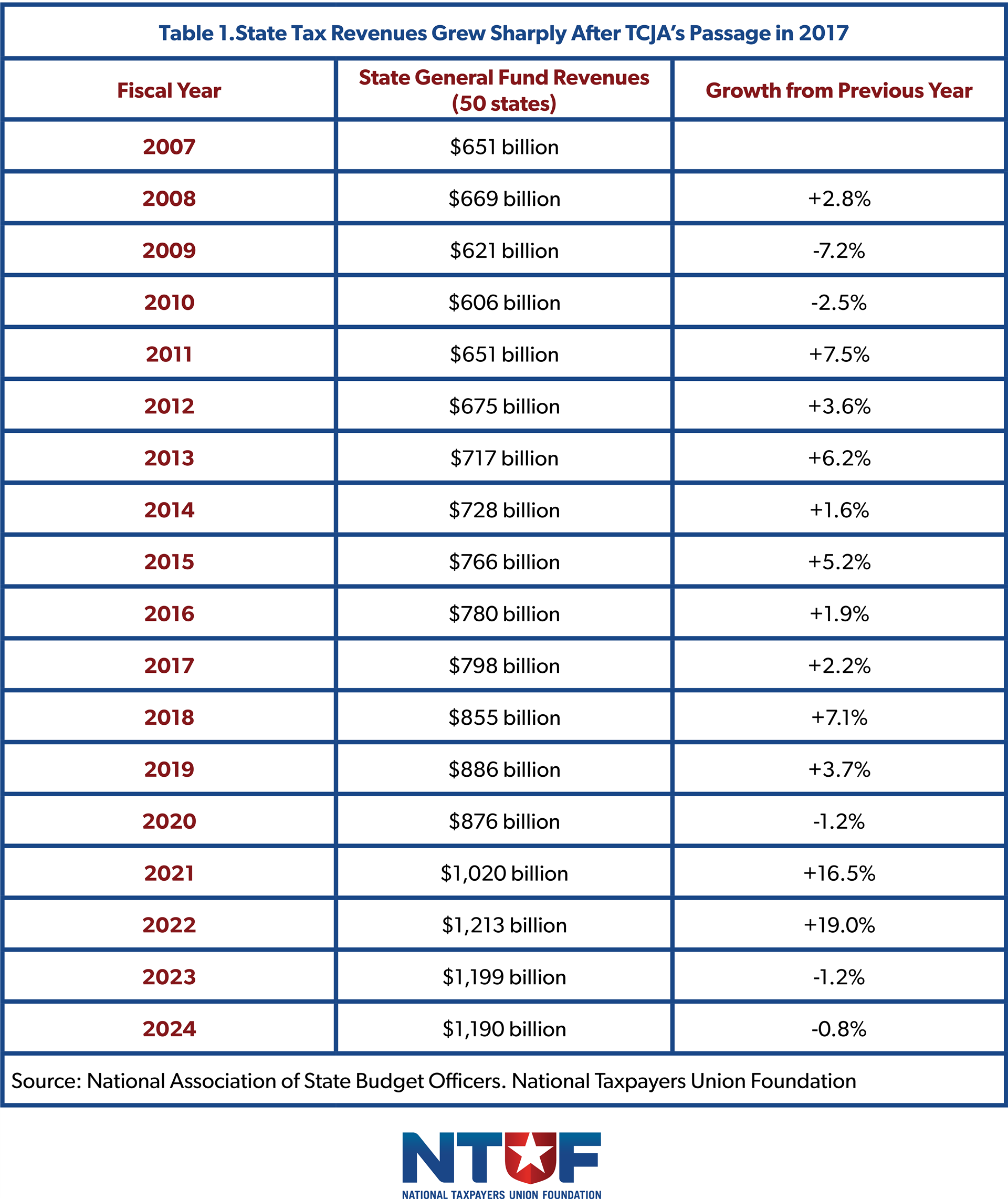

TCJA and State Revenues, 2017 to Present

State tax revenues grew sharply after TCJA’s passage, even before pandemic-related fiscal impacts. State general fund revenues (primarily collections from state income, sales, and business taxes) grew 7.1% between fiscal year 2017 (the last before TCJA took effect) and fiscal year 2018, and then another 3.7% in fiscal year 2019. This was much higher than the average 2.1% annual revenue growth in the preceding decade. Revenue growth in 2018 also exceeded economic growth that year of 4.4%.

The sharp state tax revenue growth in 2018 exceeded economic growth and remained strong in 2019. This was likely a result of structural changes and economic effects of TCJA’s passage. Pandemic-related impacts to state tax revenues occurred later. State general fund revenues then fell in fiscal year 2020, soared in 2021 and 2022, and stabilized in 2023 and after. These oscillations were likely driven by the pandemic and subsequent federal fiscal response. None of these figures have been adjusted for inflation, which was considerable in 2021 (7.0%) and 2022 (6.5%).

States have used this revenue windfall to save (rainy day funds balances grew from $52 billion in 2016 to $155 billion in 2024), increase spending, and cut their own taxes. In recent years, 27 states significantly cut taxes and 6 states moved to flat income taxes. Today, almost half of the states have either no income tax (9 states) or a flat income tax (14 states) and it may soon be a majority.

Federal Tax Cut Expiration Will Reduce Wages, State Economic Growth

TCJA expiration would raise taxes by an average of $2,955 per tax filer. There is wide geographic variation of the scope of the increase, driven primarily by individual rate cuts and interaction of the state and local tax (SALT) deduction cap. States that will see the largest average per taxpayer tax increases if TCJA expires, according to Tax Foundation calculations by state and by congressional district, are Massachusetts ($4,848), Washington ($4,567), Wyoming ($4,493), the District of Columbia ($4,160), Colorado ($3,795), and California ($3,769). The states that will see the smallest average tax increases from TCJA expiration are West Virginia ($1,423), Mississippi ($1,570), Kentucky ($1,715), New Mexico ($1,895), and Indiana ($1,937). No state would see an average tax cut if TCJA expires.

TCJA expiration would also reduce wages by 0.5%, and reduce economic growth by 1.1% over ten years. The reduction in wages and economic activity would also reduce state income, business, and sales tax collections in future years.

Conformity Rules Mean Federal Tax Expiration Will Shrink State Revenue

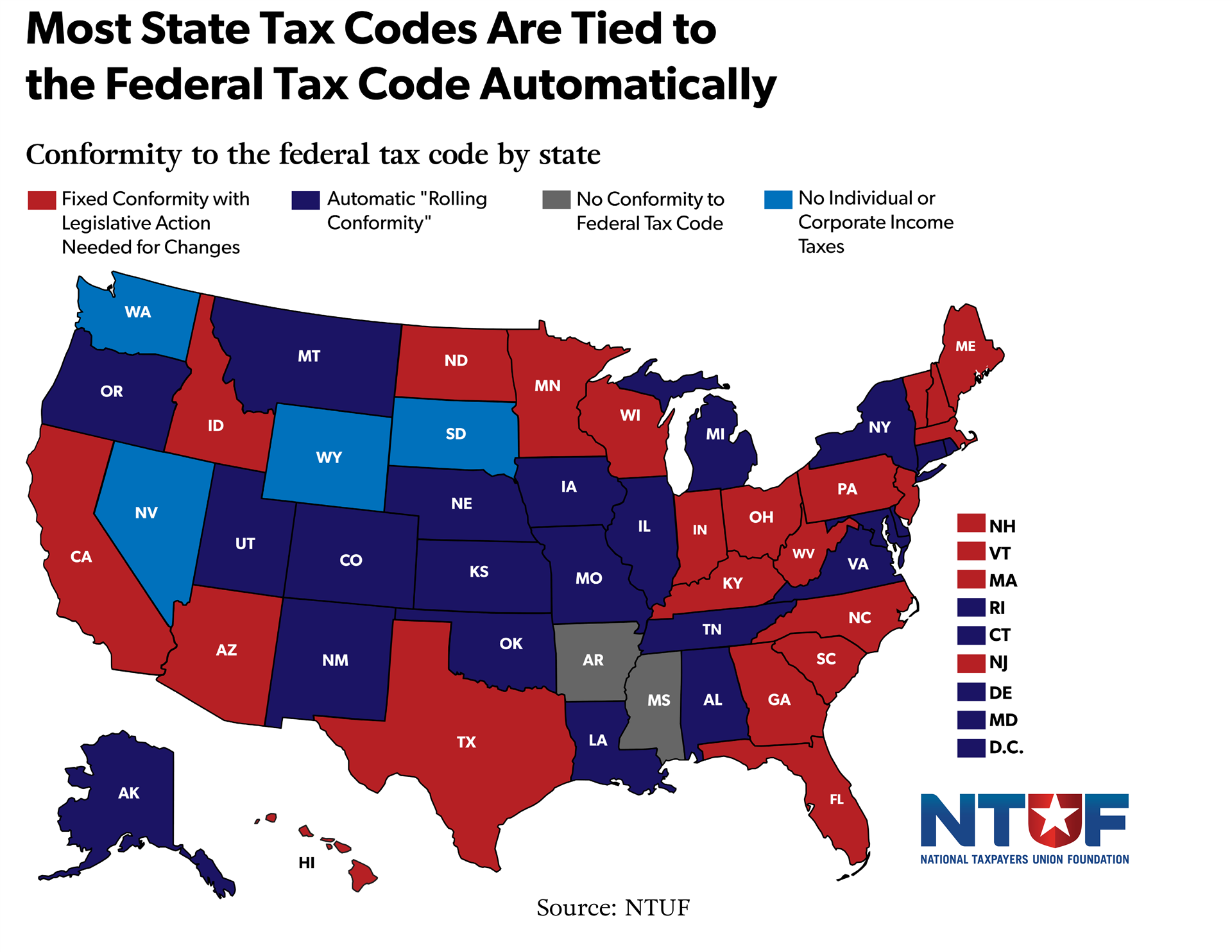

Twenty-four states automatically update their state income tax laws to match any federal tax code changes to definitions, calculations, or rules. This “rolling conformity” to federal income tax code is practiced by Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

Twenty-one other states conform to the federal income tax base only as of a certain date, called “static conformity” or “fixed conformity”: Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Many of these states pass laws incorporating federal tax changes of the past year by changing their conformity date to be January 1 of each year.

Two states use their own definitions and do not conform generally to the federal income tax code except provision by provision (Arkansas, Mississippi). Four states do not have individual or corporate income taxes to conform to (Nevada, South Dakota, Washington, and Wyoming). (While Florida, Montana, New Hampshire, Tennessee, and Texas have no state income tax, they have business taxes and are therefore listed above.)

Most State Tax Codes Are Tied to the Federal Tax Code Automatically

Conformity to the federal tax code by state

Taxpayers benefit from conformity by reducing uncertainty over what their state does or does not follow. Rolling conformity especially benefits taxpayers by avoiding discontinuity over when changes take effect and complexity from differing federal and state procedures. Rolling conformity also helped state revenues after 2017, since base-expanding federal tax changes (especially limiting the use of itemized deductions and business tax deductions) were automatically incorporated into state tax law and created a revenue windfall.

The reverse would occur with TCJA expiration. The expiration of different TCJA provisions would have differing effects on federal revenue, but fewer limits on itemized deductions would mean less federal revenue. This narrowing of the federal income tax base would also narrow state tax bases that conform. States could avoid this by “decoupling” from changes to federal itemized deductions that result from a lapse of TCJA and instead preserve current policy, or by relying exclusively on a standard deduction (see below).

Fixed conformity states may also face a problem if Congress does not act before December 31, 2025, or if it makes certain changes retroactive to dates earlier in 2025 or even further. If Congress renews TCJA provisions on January 15 retroactive to January 1, and the state fixed conformity law says it adheres to federal tax code as it stood on January 1, is it the expired or the renewed provisions? States with fixed conformity could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity, or at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

State Definitions of Income Mean TCJA Expiration May Change State Revenues

An income tax must define income, and what is and is not included in that term. Most states instruct taxpayers to start from federal Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) to calculate their state income tax. AGI is income subtracting exclusions and exemptions for policy, structural, or cost-benefit reasons; these include alimony, health and retirement account contributions, and municipal bond interest. States that adopt a federal AGI starting point automatically subtract these exclusions and exemptions for state income tax too.

Using AGI as a starting point simplifies tax calculation for taxpayers and state tax collectors alike by avoiding duplicative or contradictory state definitions of “income” and instead having everyone use the same federal definition. Some states make state income tax calculation a simple experience by imposing tax directly on the AGI calculation (Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Utah). But any federal changes to AGI calculation automatically flow through to the state tax code too. One exception is state and municipal bond interest where most states “add back” to AGI any interest income from bonds of states other than their own, as permitted by a 2007 Supreme Court decision.

Five states (Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, and South Carolina) go even further and adopt federal Taxable Income, which is AGI subtracting the standard or itemized deductions and the Section 199A pass-through deduction of TCJA. These states, by adopting a taxable income starting point, automatically subtract these deductions for state income tax. Because TCJA expiration would reduce the standard deduction and end the Section 199A deduction, most taxpayers in these five states would see higher state taxes as well as higher federal taxes because their states would automatically make these changes in their state tax code.

States that adopt federal AGI or taxable income as a starting point should monitor federal tax changes to exclusions, exemptions, and deductions. One discussed change is curtailing the federal tax exemption for state and municipal bond interest, although most states have already decoupled from this federal provision, as noted above. States that use taxable income as a starting point could, to avoid state tax increases on their own residents, consider continuing current policy on the standard deduction or Section 199A, or at least clarifying what happens if there is any temporary lapse or retroactive re-enactment of the federal taxable income definition.

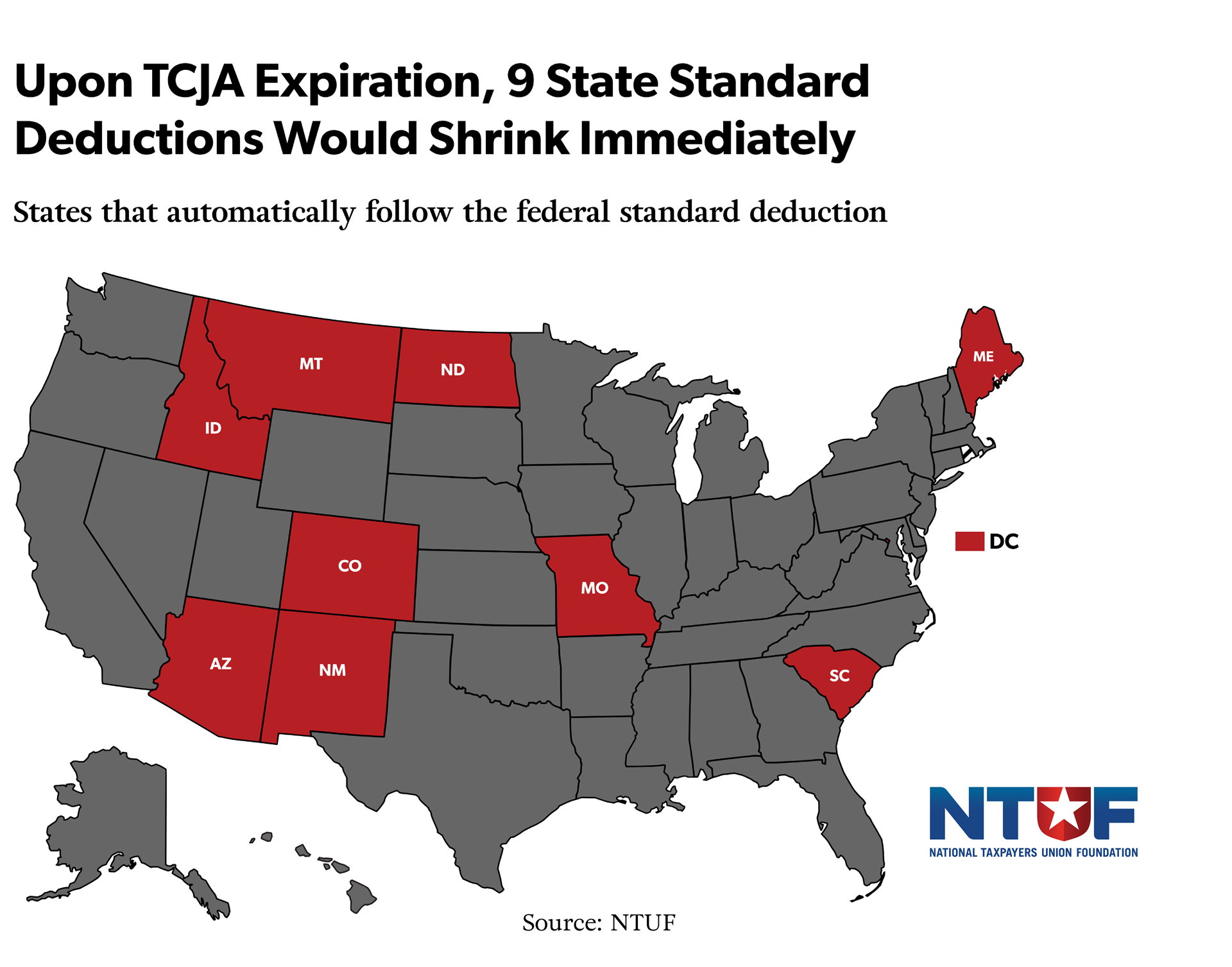

TCJA Expiration Will Shrink Some State Standard Deductions, Increasing State Taxes

The federal income tax code allows any taxpayer to take a standard deduction, instead of tracking expenses and keeping receipts to itemize deductions. In essence, the standard deduction sets a certain amount of income as tax-free.

TCJA nearly doubled the standard deduction, increasing it from $6,500 to $12,000 for single filers; from $13,000 to $24,000 for married filing jointly; and from $9,550 to $18,000 for head of households. These amounts are adjusted for inflation each year; they stand in 2025 at $15,000 (single), $30,000 (married), and $22,500 (head of household).

TCJA’s changes to the standard deduction dramatically reduced tax compliance burdens for millions of Americans: 90.1% of tax filers (150.3 million) now take the standard deduction, an increase of 30 million. NTU estimates that the expanded standard deduction saves Americans 210 million hours a year in compliance costs worth $13 billion.

If TCJA expires, the standard deduction will revert to the earlier level, falling roughly by half. This would also likely revert the taxpayer savings in compliance costs.

At the state level, nine states (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Maine, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, and South Carolina) and the District of Columbia adopt the federal standard deduction as their own. An expiration of the expanded federal standard deduction would automatically sharply reduce the standard deduction in these states, which would mean a tax increase for taxpayers in those states. To avoid this tax increase if Congress does not act, policymakers in these states could consider establishing that the standard deduction in their state is the larger of federal law or the inflation-adjusted amount from this year.

Upon TCJA Expiration, 9 State Standard Deductions Would Shrink Immediately

States that automatically follow the federal standard deduction

TCJA reduced personal exemptions in the federal tax code to zero, replacing them with the expansion of the standard deduction and the child tax credit. Prior to TCJA, taxpayers could claim a certain dollar reduction ($4,050 in 2018) for the taxpayer and each dependent. If TCJA expires, personal exemptions would return at an inflation-adjusted amount. This would reduce taxes, and state revenue, in states that adopt the federal definition of personal exemption. Most states, however, have retained a personal exemption for state taxes and would not be affected by this change: Alabama, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

TCJA Expiration Would Change Itemized Deductions, including SALT, AMT, and Mortgage Interest

TCJA made three significant changes to itemized deductions, all three of which would expire at the end of 2025 if Congress does not act:

- SALT Cap: TCJA capped the amount that itemizing taxpayers can deduct from state and local property and either income or sales taxes, at $10,000 per filer. This SALT cap amount is not adjusted for inflation. Thirty-six states have adopted a “SALT cap workaround,” allowing some taxpayers to continue deducting greater than $10,000 per filer by recategorizing individual SALT payments as business entity SALT payments. The IRS has acknowledged the permissibility of such state workarounds.

- AMT Patch: TCJA raised the income level at which taxpayers would face the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), a parallel tax code requiring a minimum percentage of taxes to be paid by taxpayers who take excessive deductions such as SALT. AMT was created after a 1969 study revealed 155 high-income households paid zero federal income tax, but because the AMT exemption amount was not adjusted for inflation until 2013, it ultimately was imposed on millions of taxpayers. Congress routinely “patched” the AMT on a one-year or two-year basis to mitigate how many taxpayers had to pay it. TCJA made this patch permanent, at least until TCJA expires after 2025.

- Mortgage Interest Deduction: While mortgage interest remains deductible for itemizing taxpayers, TCJA reduced the maximum mortgage amount for purposes of the deduction from $1 million to $750,000 of a first or second home. This amount is not adjusted for inflation.

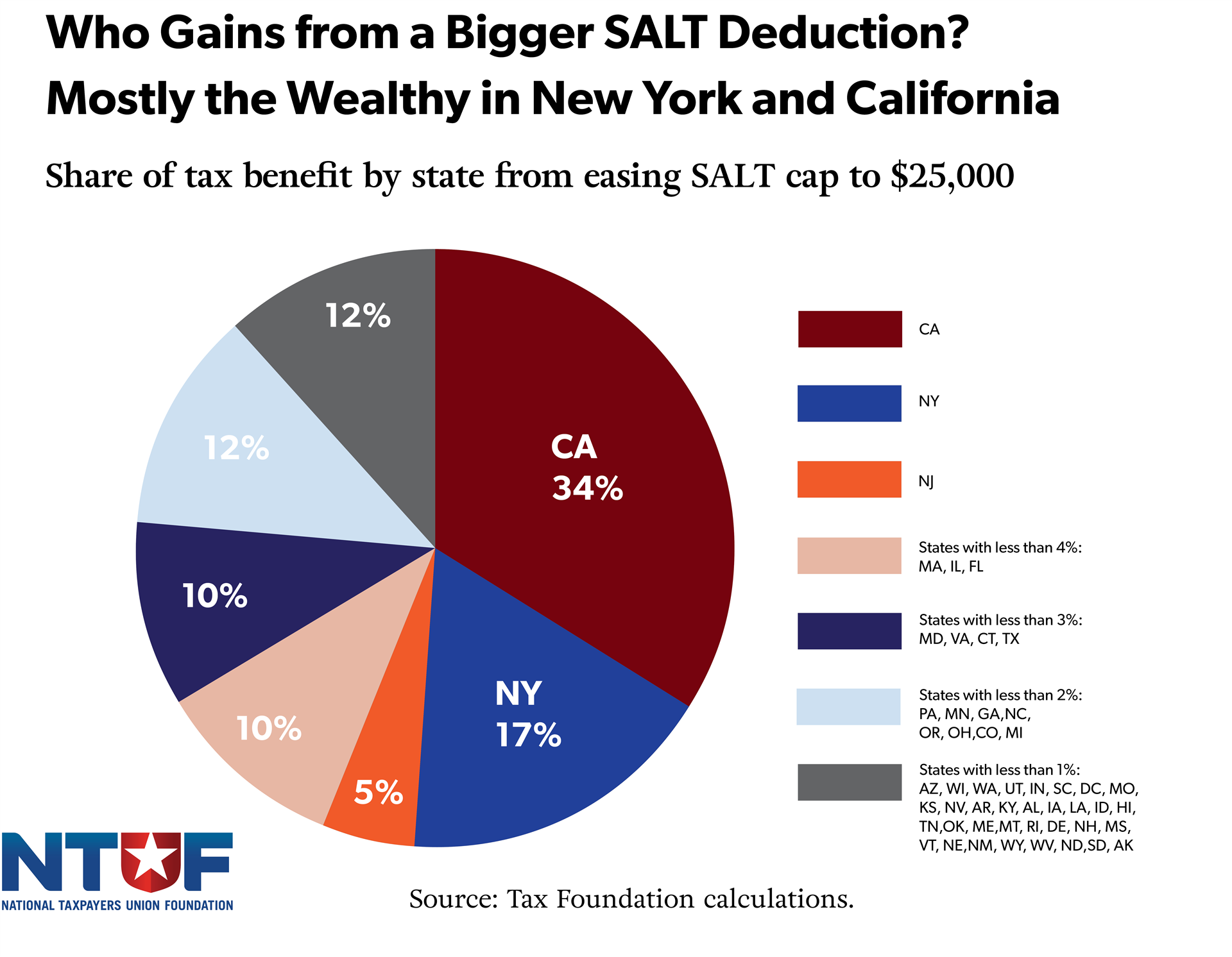

The SALT cap and the AMT patch did not directly affect state tax revenues, since today no state allows a circular deduction of state taxes paid from state income tax and no state was coupled to the AMT instead of to the regular federal income tax. But some states have frequently raised the SALT cap as an issue of concern since some perceive it as targeting, or reducing the federal tax preference toward, high-income areas of high-tax states like California, Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. Policymakers from these states will likely pressure for a higher, or no, SALT cap.

While the state and local tax deduction was more generous before TCJA, the AMT took away much of that generosity for many high-income taxpayers in high-tax states. Raising or eliminating the SALT cap while retaining the AMT patch and state SALT cap workaround laws would result in more generous benefits for high-income taxpayers than before TCJA.

The SALT cap also replaced the Pease limitation, a complex reduction of the value of itemized deductions by an escalating percent above a certain income threshold. Over half of the tax reduction benefit of easing the SALT cap from $10,000 to $25,000 would accrue to just two states: California ($18 billion per year, or 34.1%) and New York ($9 billion per year, or 17.3%.)

Who Gains from a Bigger SALT Tax Deduction? Mostly the Wealthy in New York and California

Share of tax benefit by state from easing SALT cap to $25,000

State policymakers who do not represent high-income, high-tax states could communicate their views on the SALT cap to federal policymakers, and, at minimum, could review their SALT cap workaround laws to ensure their effects change if the federal SALT cap becomes more generous.

The mortgage interest deduction maximum mortgage amount would revert to the higher $1 million level if TCJA expires. This change would reduce tax revenue for the five states that use federal taxable income as their income starting point (Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, and South Carolina, see above). But for any state that allows itemized deductions, TCJA expiration would somewhat reduce revenue except for four states that have retained the $1 million limit (Arkansas, California, Hawaii, and New York). State policymakers could avoid any changes by retaining the $750,000 limit in state tax law.

TCJA International Provisions Will Mostly Remain, But States Should Reconsider Complexity of Add-On Taxes

TCJA created new international business tax provisions to protect the U.S. tax base and increase international tax competition. Among those provisions was the world’s first global minimum tax, known as the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) tax. GILTI applies to certain foreign income of a U.S. parent company at a rate of 10.5%, with an effective rate of 13.125% when combined with partially creditable foreign tax credits.

GILTI works alongside TCJA’s other international tax policy levers, including the Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII) tax and the Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT). FDII is a tax of 13.125% on export income from U.S.-based intangible assets, and BEAT is a 10% minimum tax applied when related companies engage in cross-border payments for profit-shifting purposes. All three of these international taxes will undergo a rate increase after 2025 as TCJA expires, unless modified by Congress. GILTI will increase to 16.406% with an effective rate of 13.125%, FDII will increase to 16.406%, and BEAT will increase to 12.5%.

Most states did not couple to GILTI, excluding GILTI income from state taxes entirely. This treatment makes good policy sense, since the income is earned overseas and not within any U.S. state with a rate calibrated to deter profit-shifting. But 20 states tax GILTI income, including up to 50% within their state tax base: Alaska (20%), Colorado (50%), Connecticut (50%), Delaware (50%), Idaho (15%), Maine (50%), Maryland (50%), Massachusetts (5%), Minnesota (50%), Montana (20%), Nebraska (50%), New Hampshire (50%), New Jersey (5%), New York (5%), Oregon (20%), Rhode Island (50%), Tennessee (5%), Utah (50%), Vermont (50%), West Virginia (50%), and the District of Columbia (50%).

Policymakers in these states should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

TCJA Expiration Means Federal Death Taxes Go Up

TCJA doubled the estate tax exemption amount, from $5.49 million in 2017 to $10.98 million. The amount is annually adjusted for inflation, and stands at $13.99 million in 2025. TCJA expiration would revert the estate tax exemption level to the pre-TCJA amount after 2025, cutting it in half.

Before the passage of the TCJA, we estimated that the 12,411 estate tax filers spent a combined 2,099,259 hours on estate tax compliance worth $630 million. Far more estates structure themselves to avoid the tax, at a cost many times greater than that. TCJA led to a sharp decline in the number of estates subject to the tax, with the number of taxable estates dropping from 5,185 in 2017 to 2,584 in 2021. But revenue from the estate tax stayed relatively steady—dropping only from $19.9 billion in 2017 to $18.4 billion in 2021.

The federal estate tax changes had minimal impact on state revenues because only 12 states and the District of Columbia still have an estate tax, and, of those, only Connecticut still couples to the federal estate tax threshold. Delaware, Hawaii, and the District of Columbia decoupled from the federal estate tax threshold since TCJA was passed, with Hawaii repealing the tax entirely. State policymakers, especially in Connecticut, should review their state estate tax threshold law to understand how it will operate in the event of expiration of the higher federal threshold.

Some States Should Consider Adopting Federal Standard for Business Losses

TCJA adopted limitations on business net operating losses (NOLs). NOLs correct for the arbitrariness of taxes being calculated on an annual basis, allowing losses in one year to offset profits in another. When a loss can be used to offset future profits, it is called a carryforward; when a loss can be used to offset past profits, it is called a carryback.

Prior to TCJA, federal law allowed NOLs to be fully deductible, for up to 20 years carryforward and 3 years carryback. TCJA adopted a new federal standard of being 80% deductible with unlimited years carryforward and no carrybacks. NOL changes were enacted permanently and will not automatically change if TCJA expires.

Eighteen states conform to current federal treatment of NOLs, avoiding conflicting rules between federal and state tax: Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Mississippi, Missouri, and New York retain the pre-TCJA treatment of NOLs (with New York offering 3 year carrybacks), and 10 states retain the pre-TCJA unlimited carryforwards for 20 years but have abolished or curtailed carrybacks (Arizona, Connecticut (30 years), Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Wisconsin). These states are arguably more generous than current federal law, but at the cost of businesses needing to calculate NOLs differently for federal and state tax returns. Policymakers in these states can retain the status quo with no action.

The remaining states both decoupled from federal NOL treatment and are less generous. These 13 states and their carryforward policies are: Alabama (15 years), Arkansas (8 years), California (NOLs disallowed entirely), Illinois (capped at $500,000), Michigan (10 years), Minnesota (15 years), Montana (10 years), New Hampshire (10 years), North Carolina (15 years), Oregon (15 years), Pennsylvania (capped at 40%), Rhode Island (5 years), Tennessee (15 years), and Vermont (10 years). These states’ NOL policies impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states.

Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

States May Be Affected by Potential Changes to Business Interest Expense Limitation

Businesses are taxed on profits and thus can generally deduct all expenses.

Prior to TCJA, this included the cost of interest payments on debt. To counter a tax code preference for debt-financing over equity-financing, TCJA Section 163(j) limited the amount of interest that a business can deduct to 30% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) starting in 2018. The 30% limit was temporarily increased to 50% for 2019 and 2020 as part of the federal CARES Act pandemic relief bill. TCJA also scheduled a further limit on interest deductions to 30% of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT), which took effect in 2022. This 30% of EBIT remains in effect and does not expire with TCJA, although business groups have discussed seeking to restore the EBITDA measure.

States therefore have had several options for their own interest deductibility provisions: conform to federal law whatever it may be, pre-TCJA 100% interest deductibility, the earlier 30% EBITDA limit, the temporary CARES Act 50% limit, or something else.

Thirty-two states conform fully to the federal interest expense limitation, reducing complexity for business taxpayers: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Policymakers in these states should monitor federal debate on Section 163(j) and evaluate how any changes may affect their state. States that couple to 163(j) but not to full expensing (see below) should consider adopting full expensing due to the complexity involved with recalculating interest while removing the effect of 100% bonus depreciation.

Eleven remaining states have decoupled from current Section 163(j), with one state allowing a 50% limit to interest deductibility (Virginia) and ten states retaining pre-TCJA full deductibility of interest expense (California, Connecticut, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Wisconsin).

Policymakers in these states should monitor the federal debate over EBIT and EBITDA for any changes, but continuation of the status quo is not dependent on TCJA renewal.

States Should Pursue Full, Permanent Business Expensing

A major pro-growth element of the TCJA was full expensing for short-lived capital assets, such as equipment. Under the pre-TCJA federal tax code, businesses must calculate the cost of such investments by distributing the total cost over the expected life of the investment, as determined through depreciation schedules. By accounting for only a portion of the expense realized, a business’s profits are artificially inflated in early years, thus increasing the tax liability.

TCJA instead enacted 100% bonus depreciation, better described as full expensing, which allows businesses to deduct the full cost of short-lived assets in the year the expense was incurred.

This provision was not permanent and the percentage of bonus depreciation allowed under the TCJA has gradually declined, as set in federal tax code Section 168(k). TCJA allowed for 100% bonus depreciation for tax years 2018 through 2022, with a phase down to 80% in 2023, 60% in 2024, 40% in 2025, and 20% in 2026, before reverting to pre-TCJA depreciation in tax year 2027.

Two states (Mississippi and Oklahoma) have decoupled from Section 168(k) to preserve full expensing regardless of what the federal government may do with TCJA renewal. These states have enacted good policy that removes an artificial penalty on equipment investment in their states.

Sixteen states conform to federal Section 168(k) on expensing, thus offering full expensing from 2018 to 2022 and now at declining percentages each year: Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Tennessee, Utah, and West Virginia. These states will automatically revert back to full expensing if the federal government does so, but could also independently enact 100% full expensing to revert to the pro-investment policy they had prior to 2023.

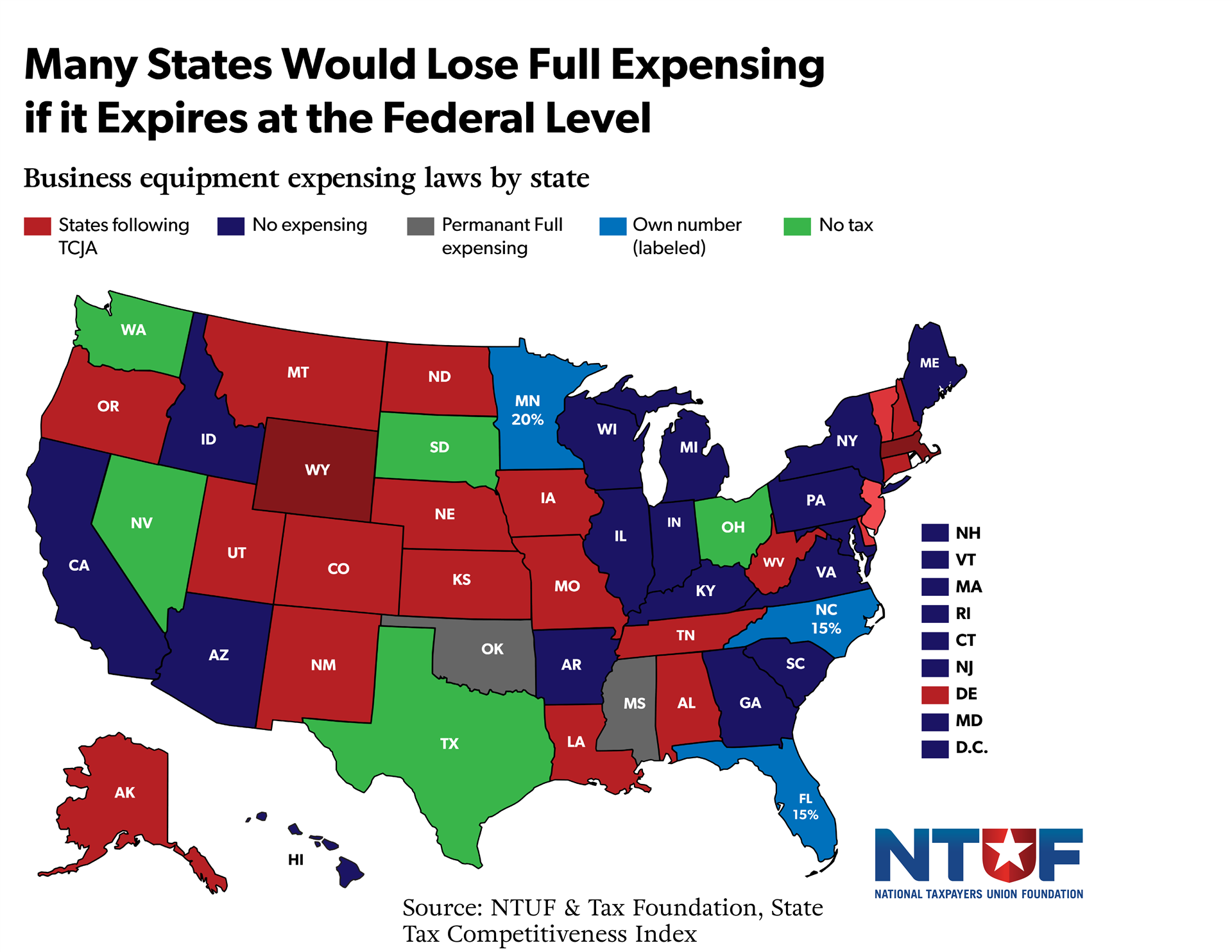

Many States Would Lose Full Expensing if it Expires at the Federal Level

Business equipment expensing laws by state

Source: NTUF & Tax Foundation, State Tax Competitiveness Index

Most states, unfortunately, currently decouple from federal Section 168(k) to provide less generous or even no expensing for purchases of new equipment: Arizona (0%), Arkansas (0%), California (0%), Connecticut (0%), Florida (15%), Georgia (0%), Hawaii (0%), Idaho (0%), Illinois (0%), Indiana (0%), Kentucky (0%), Maine (0%), Maryland (0%), Massachusetts (0%), Michigan (0%), Minnesota (20%), New Hampshire (0%), New Jersey (0%), New York (0%), North Carolina (15%), Pennsylvania (0%), Rhode Island (0%), South Carolina (0%), Vermont (0%), Virginia (0%), Wisconsin (0%), and the District of Columbia (0%). Policymakers in these states should consider adopting 100% full expensing or recoupling to federal Section 168(k) to reduce the tax penalty on purchases of new business equipment. This is especially true for states that have coupled to federal Section 163(j) limiting business interest deductibility, since the provisions are meant to operate together.

States Should Pay Attention to New Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Automobile Loan Interest

President Trump has proposed that the TCJA extension also include other tax reductions, including excluding or exempting tip income, overtime pay, Social Security income, and automobile loan interest from federal tax. Depending on how the reductions are designed, some of the changes could shield large amounts of income from taxation.

Under the current federal tax code, all but one of these items are included in the definition of income and are thus taxable in full. Social Security benefits have been subject to federal income tax in part since 1983, as a proxy for means-adjusting Social Security benefits for high-income individuals. The standard deduction and a Social Security “combined income” exemption level shield all Social Security benefits from taxation for low-income individuals and many middle-income individuals. As a result, the income tax on Social Security benefits today applies to approximately half of retired households, those with additional income sources such as investment income, primarily because the taxation thresholds are not adjusted for inflation. These households pay income tax on up to 85% of their Social Security benefits.

If any of the proposed reductions are structured as part of the calculation of AGI (an exclusion, exemption, or “above-the-line” deduction available even to taxpayers who do not itemize deductions), they would also be automatically adopted as part of state tax codes in any state that has rolling conformity to the federal tax code: Alabama, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

If any of the proposed reductions are structured as one of the itemized deductions, they would be adopted as a part of state tax codes for only those states that use itemized deductions on the federal tax return as a starting point and in four other states that use taxable income and automatically conform (Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, and North Dakota).

If any of the proposed reductions are structured as a tax credit, these would not automatically flow through to any state income tax.

State policymakers should closely monitor the federal debate on these provisions and ensure their state tax code couples or decouples to provisions based on deliberate choice by the state.

States Should Make Tax Code Compliance Less Burdensome to Taxpayers

The total time Americans spend on federal tax compliance peaked in 2017 at just over 8 billion hours. The burden eased to 6 billion hours by 2020, thanks in large part to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Key reforms—like increasing the standard deduction, trimming the number of filers subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax, and simplifying Form 1040—helped reduce paperwork. But the burden has begun creeping back up, reaching 7 million hours again this year, an annual deadweight loss of $464 billion.

States can exacerbate or minimize that compliance burden when it comes to their taxes. States that conform to the federal tax code, adopt AGI or taxable income as a starting point, and minimize decoupling from federal provisions can enable individual and business taxpayers to complete their state tax filings with a minimum of additional time and expense. By contrast, states add to the tax compliance burden if they conform only periodically, require excessive recalculation of items on the federal return, or decouple from pro-growth provisions like full expensing. States should track how long it takes the average individual or business taxpayer to complete their state tax return, and if the answer is more than a few hours, policymakers should invite input on how to do better.

State policymakers can also minimize unnecessary friction between state tax provisions. For example, to avoid excessive compliance burdens for remote or mobile workers in the state for only brief periods, states could join Indiana and Montana in adopting 30-day filing and withholding thresholds. Excessively burdensome “convenience of the employer” rules, that extend the reach of one state’s tax system countrywide, could be dropped by Alabama, Delaware, Nebraska, New York, and Pennsylvania. States could adopt dollar thresholds only for out-of-state businesses to comply with sales tax collection, rather than dollar-or-transaction thresholds still followed by about half of states. States could make design changes to unemployment insurance programs, including cross-matching data with other states, to reduce payroll tax burdens. And states can ensure that bulwarks against discriminatory taxes on interstate commerce, such as the Internet Tax Freedom Act (ITFA) and the Interstate Income Act (P.L. 86-272), are adhered to by state legislation and administrative rulings.

Conclusion: State Policymakers Have Power to Relieve State Tax Burdens, Provide Certainty

The expiration of the TCJA at the end of 2025 poses significant economic and fiscal challenges for states across the nation. While states experienced substantial revenue growth following TCJA’s enactment, these gains are at risk unless state policymakers proactively address conformity to federal tax provisions, preserve simplification measures like the expanded standard deduction, and maintain pro-growth policies such as full business expensing. To navigate the uncertainty surrounding congressional action, states should closely evaluate their tax conformity laws, prepare for potential revenue fluctuations, and actively communicate the importance of stability and clarity in federal tax policy to their federal counterparts.

Recommendations to Policymakers by State

Alabama

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Alabama taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,192 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: The state automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Business Net Operating Loss Treatment: The state’s NOL policies are less generous than the federal government and impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states. Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

- Business Expensing Conformity: The state conforms to federal Section 168(k), which means only 60% expensing for business investments this year and less in future years. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing, particularly since Alabama conforms to the Section 163(j) limit on interest expense and the two provisions were meant to work together.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Alabama (0.3%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Alaska

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Alaska taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,380 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: The state automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Alaska does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing Conformity: The state conforms to federal Section 168(k), which means only 60% expensing for business investments this year and less in future years. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing, particularly since Alaska conforms to the Section 163(j) limit on interest expense and the two provisions were meant to work together.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Alaska (0.01%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Arizona

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Arizona taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,824 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Generous Standard Deduction: An expiration of the expanded federal standard deduction would automatically sharply reduce the state standard deduction, which would mean a tax increase for most taxpayers. To avoid this tax increase if Congress does not act, policymakers in these states could consider establishing that the standard deduction in their state is the larger of federal law or the inflation-adjusted amount from this year.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

Arkansas

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Arkansas taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,325 per filer.

- Business Net Operating Loss Treatment: The state’s NOL policies are less generous than the federal government and impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states. Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Arkansas (0.95%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

California

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, California taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $3,769 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Net Operating Loss Treatment: The state’s NOL policies are less generous than the federal government and impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states. Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

Colorado

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Colorado taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $3,795 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Colorado automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Federal Taxable Income Starting Point: States using this starting point automatically adopt any federal tax exclusion, exemption, or deduction. States that use taxable income as a starting point could, to avoid state tax increases on their own residents, consider continuing current policy on the standard deduction or Section 199A, or at least clarifying what happens if there is any temporary lapse or retroactive re-enactment of the federal taxable income definition.

- Generous Standard Deduction: An expiration of the expanded federal standard deduction would automatically sharply reduce the state standard deduction, which would mean a tax increase for most taxpayers. To avoid this tax increase if Congress does not act, policymakers in these states could consider establishing that the standard deduction in their state is the larger of federal law or the inflation-adjusted amount from this year.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Colorado does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing Conformity: Colorado conforms to federal Section 168(k), which means only 60% expensing for business investments this year and less in future years. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing, particularly since the state conforms to the Section 163(j) limit on interest expense and the two provisions were meant to work together.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

Connecticut

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Connecticut taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $3,510 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Connecticut automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Estate Tax Threshold: Connecticut couples to the federal estate tax threshold. To prevent a sudden reduction in the threshold if TCJA expires, policymakers could clarify that it continues at the present level, adjusted for inflation, if the federal exemption level is lower.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Connecticut does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing: Connecticut does not adopt full expensing business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

Delaware

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Delaware taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,418 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Delaware automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Delaware does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing Conformity: The state conforms to federal Section 168(k), which means only 60% expensing for business investments this year and less in future years. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing, particularly since Delaware conforms to the Section 163(j) limit on interest expense and the two provisions were meant to work together.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Delaware (0.2%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

District of Columbia

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, District of Columbia taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $4,160 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: The District of Columbia automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the District’s tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but the District of Columbia does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing: The District does not adopt full expensing for business investments. Policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the District’s tax system.

Florida

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Florida taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $3,650 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

Georgia

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Georgia taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,680 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Expensing: Georgia does not adopt full expensing business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

Hawaii

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Hawaii taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,689 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

Idaho

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Idaho taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,647 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Generous Standard Deduction: An expiration of the expanded federal standard deduction would automatically sharply reduce the state standard deduction, which would mean a tax increase for most taxpayers. To avoid this tax increase if Congress does not act, policymakers in Idaho could consider establishing that the standard deduction in their state is the larger of federal law or the inflation-adjusted amount from this year.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Idaho does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Idaho (0.3%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Illinois

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Illinois taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,792 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Illinois automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Business Net Operating Loss Treatment: Illinois’s NOL policies are less generous than the federal government and impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states. Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

Indiana

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Indiana taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $1,937 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Expensing: Indiana does not adopt full expensing business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

Iowa

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Iowa taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,063 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Iowa automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Business Expensing: Iowa does not adopt full expensing business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Iowa (0.3%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Kansas

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Kansas taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,369 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Kansas automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Business Expensing: Kansas does not adopt full expensing business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Kansas (0.5%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Kentucky

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Kentucky taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $1,715 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Kentucky (0.4%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Louisiana

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Louisiana taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,135 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Louisiana automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Business Expensing Conformity: Louisiana conforms to federal Section 168(k), which means only 60% expensing for business investments this year and less in future years. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing, particularly since the state conforms to the Section 163(j) limit on interest expense and the two provisions were meant to work together.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Louisiana (0.3%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Maine

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Maine taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,226 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Generous Standard Deduction: An expiration of the expanded federal standard deduction would automatically sharply reduce the state standard deduction, which would mean a tax increase for most taxpayers. To avoid this tax increase if Congress does not act, policymakers in Maine could consider establishing that the standard deduction in their state is the larger of federal law or the inflation-adjusted amount from this year.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Maine does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Maine (0.2%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Maryland

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Maryland taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,806 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Maryland automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Maryland does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

Massachusetts

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Massachusetts taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $4,848 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

Michigan

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Michigan taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,151 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Michigan automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Business Net Operating Loss Treatment: Michigan’s NOL policies are less generous than the federal government and impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states. Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

Minnesota

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Minnesota taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,360 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Net Operating Loss Treatment: Minnesota’s NOL policies are less generous than the federal government and impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states. Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

Mississippi

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Mississippi taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $1,570 per filer.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Mississippi (0.2%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Missouri

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Missouri taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,209 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Missouri automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Generous Standard Deduction: An expiration of the expanded federal standard deduction would automatically sharply reduce the state standard deduction, which would mean a tax increase for most taxpayers. To avoid this tax increase if Congress does not act, policymakers in Missouri could consider establishing that the standard deduction in their state is the larger of federal law or the inflation-adjusted amount from this year.

- Business Expensing: Missouri does not adopt full expensing business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Missouri (0.6%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Montana

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Montana taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,698 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Montana automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- Federal Taxable Income Starting Point: States using this starting point automatically adopt any federal tax exclusion, exemption, or deduction. States that use taxable income as a starting point could, to avoid state tax increases on their own residents, consider continuing current policy on the standard deduction or Section 199A, or at least clarifying what happens if there is any temporary lapse or retroactive re-enactment of the federal taxable income definition.

- Generous Standard Deduction: An expiration of the expanded federal standard deduction would automatically sharply reduce the state standard deduction, which would mean a tax increase for most taxpayers. To avoid this tax increase if Congress does not act, policymakers in Montana could consider establishing that the standard deduction in their state is the larger of federal law or the inflation-adjusted amount from this year.

- Business Net Operating Loss Treatment: Montana’s NOL policies are less generous than the federal government and impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states. Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Montana does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing Conformity: Montana conforms to federal Section 168(k), which means only 60% expensing for business investments this year and less in future years. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing, particularly since the state conforms to the Section 163(j) limit on interest expense and the two provisions were meant to work together.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Montana (0.2%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Nebraska

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Nebraska taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,443 per filer.

- Rolling Conformity: Nebraska automatically follows the federal tax code, so any federal action (or lack of action) will automatically apply to the state tax code. Policymakers should consider preserving elements of the current tax code in case TCJA expires.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but Nebraska does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing Conformity: Nebraska conforms to federal Section 168(k), which means only 60% expensing for business investments this year and less in future years. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing, particularly since the state conforms to the Section 163(j) limit on interest expense and the two provisions were meant to work together.

- Monitor Proposals on Tips, Overtime, Social Security, and Auto Loans: Depending on how these proposals are structured in any federal enactment, they could automatically flow through to the state tax system.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Nebraska (0.1%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

Nevada

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, Nevada taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $3,681 per filer.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not Nevada (0.5%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

New Hampshire

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, New Hampshire taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $3,632 per filer.

- Fixed Conformity: States that must affirmatively conform with the federal tax code as of a certain date could specify that their law incorporates any retroactive federal provisions enacted after the date of fixed conformity. Policymakers should at least be conscious of any retroactive provisions when selecting their date of fixed conformity.

- Business Net Operating Loss Treatment: New Hampshire’s NOL policies are less generous than the federal government and impose compliance costs due to lack of synchronization with the federal code and are uncompetitive with most other states. Policymakers in these states should reconsider their NOL treatment.

- GILTI Inclusion: The federal minimum tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is part of a mechanism of taxes and credits to deter cross-border profit-shifting. The income is not earned domestically and should not be taxed by any state, but New Hampshire does so. Policymakers should review how their provisions interact with the scheduled change in GILTI rates, whether they would be impacted by a modification or extension of TCJA, and whether the complexity caused by their inclusion of GILTI is justified.

- Business Expensing: The state does not adopt full expensing for business investments. State policymakers could adopt 100% full expensing regardless of whether federal full expensing is renewed.

- SALT Cap Easing Would Be Inequitable: Most of the tax cut benefit from easing the SALT cap would accrue to California (34%) and New York (17%), not New Hampshire (0.2%). State policymakers should communicate to federal counterparts that easing the SALT cap would only benefit other, higher-tax states, and is not a priority.

New Jersey

- Average Tax Increase: If TCJA expires, New Jersey taxpayers will face an average tax increase of $2,794 per filer.