(pdf)

Remote work has changed since the midst of the pandemic. In May 2020, 70 percent of remote-capable American employees worked fully remotely, a drastic jump from January 2019 when 60 percent worked fully on-site. The percentage of fully-remote employees has dropped back under 30 percent as of May 2023, but that does not mean that they have gone back to the old style of work. Rather, a majority has switched to a hybrid work schedule. Full-time on-site work has gone up, but only from 12 percent in May 2020 to 20 percent in May 2023.

The upshot is that anyone expecting remote work to be a pandemic-induced fad that would fade away along with COVID-19 need to recalibrate how they respond to the new reality. Remote work can be an opportunity to states willing to make their tax codes hospitable and convenient to remote and mobile workers, but it will be a problem for any state determined to stick to tax policies that do not acknowledge a changing economy.

[%interactivemap%]

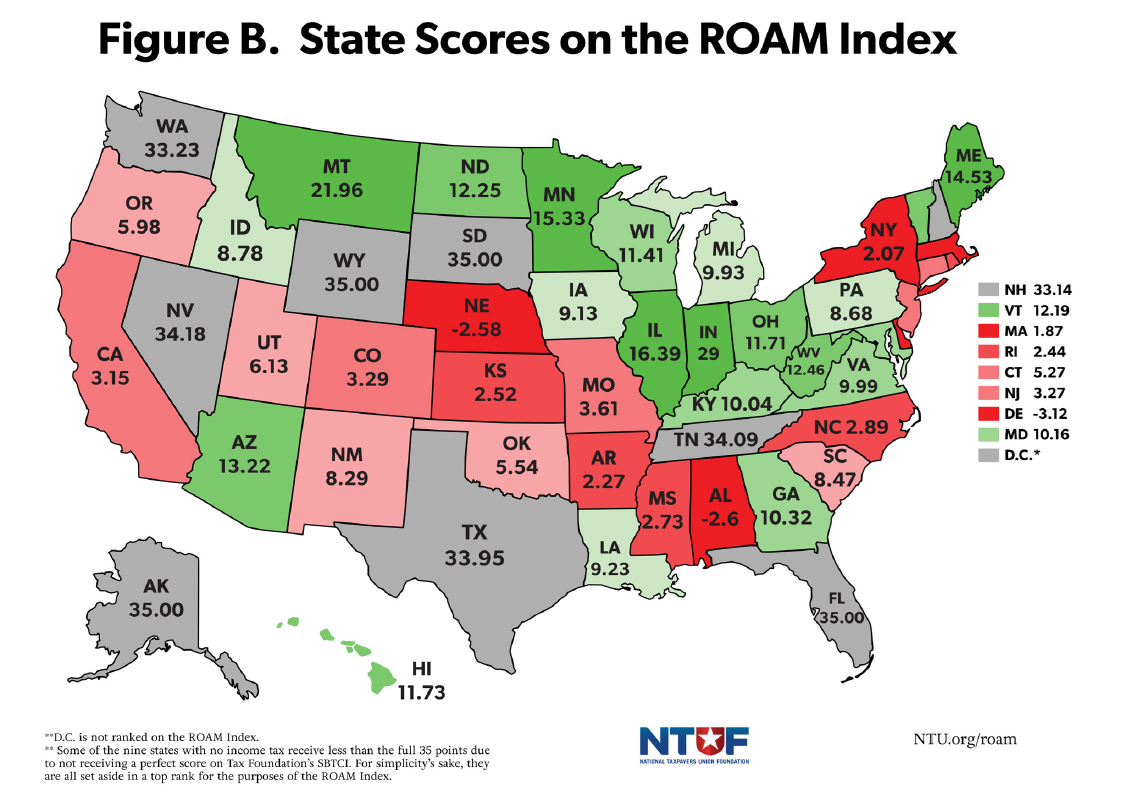

The Remote Obligations and Mobility (ROAM) Index provides a comprehensive, data-grounded ranking of each of the fifty states’ tax codes in terms of how they affect remote and mobile workers. We also provide a blueprint for those seeking to improve their state’s treatment of remote and mobile workers.

Indiana and Montana, having passed filing and withholding thresholds of greater than 30 days during 2023, are now the highest-ranked states with an individual income tax on the ROAM Index. Delaware and Alabama, two states with so-called “convenience of the employer” rules and no beneficial policies for remote and mobile workers, come in last.

Factors Considered in the ROAM Index

The ROAM Index considers five policies in evaluating a state’s individual income tax code for how it affects remote and mobile workers:

- Filing thresholds - Thresholds that taxpayers must exceed before being required to file an income tax return in a state. States with a threshold that exempts taxpayers from filing obligations until they spend more than 30 days working in the state receive the highest score.

- Reciprocity agreements - Agreements between states that allow taxpayers who commute across state lines to pay income taxes only to their state of residence. States receive a score based on the percentage of incoming commuters covered by reciprocity agreements.

- So-called “Convenience of the employer” rules - Requirements that taxpayers who switch from commuting into a state to working remotely in another state must keep paying income taxes to the state they used to commute into so long as they could possibly have continued commuting. States without these damaging policies avoid penalties to their score.

- Individual income tax code - Complex and burdensome income tax codes receive a lower score.

- Withholding thresholds - Thresholds that employees must exceed in a state before employers are required to withhold income taxes on the employees’ behalf. States with a threshold that exempts employers from withholding obligations until employees spend more than 30 days working in the state receive the highest score.

The nine states with no individual income tax code are the top-ranked states, as there is, by definition, no income tax burden on remote and mobile workers. Though there are differences between these states in terms of their treatment of dividend and capital gains income, none of these differences place any filing or withholding burdens on employees working in their states. The District of Columbia is also not ranked under the ROAM Index, but would receive the next highest score after the states with no individual income tax because it is prohibited by its Home Rule Act from taxing nonresidents. Consequently, D.C. lacks the ability to impose harmful tax obligations on remote workers even if it wanted to.

Some of the biggest changes and remote work-related developments since the 2023 edition of the ROAM Index are highlighted below.

Biggest Changes/Developments

- Indiana and Montana passed greater than 30-day filing and withholding thresholds, consequently becoming the states with the least burdensome individual income tax codes for remote and mobile workers.

- Mobile workforce legislation was considered in Kansas, Minnesota, and Nebraska, which would have substantially improved each state’s score on the ROAM Index.

- An Alabama Tax Court decision introduced a new convenience of the employer rule in the state, while New Jersey imposed a retaliatory convenience rule modeled after Connecticut’s.

- NTUF made some changes to the ROAM Index’s scoring methodology, including for states that have mobile workforce legislation problematically contingent on various requirements.

- Newly updated census data allowed for a more up-to-date picture of commuting flows.

Below is a further analysis of each of the factors considered in the ROAM Index.

Filing Thresholds

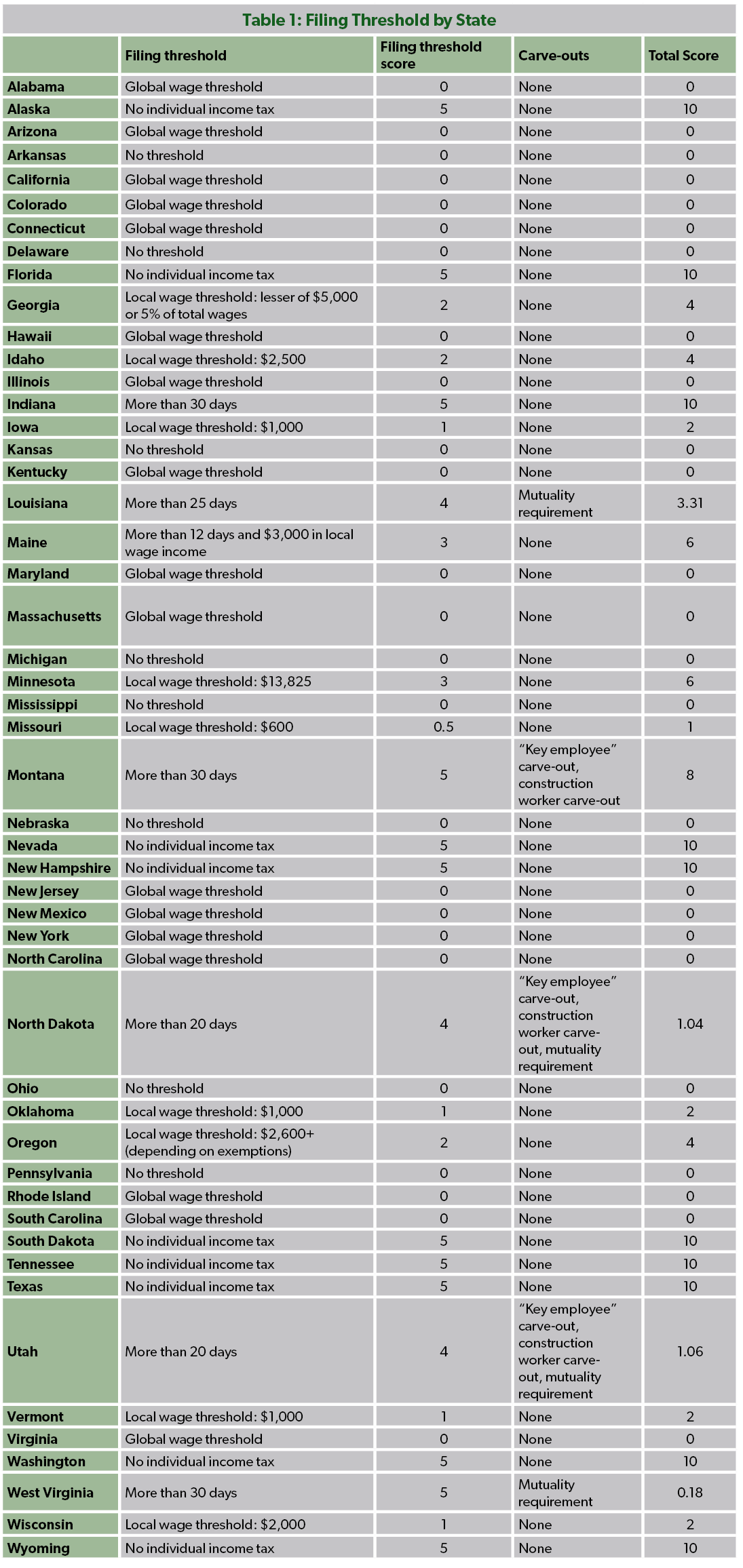

Filing thresholds represent how long a taxpayer must work in a state before the taxpayer must file an income tax return in that state. Different states have different rules about the requirements taxpayers must fulfill before having to file an individual income tax return in each state.

In a majority of states, nearly all taxpayers must file an individual income tax return in that state from the very first day they earn income in that state, a requirement that most taxpayers are likely not even aware of. While last year we made a distinction between states that had no threshold at all or states that had a very low global income threshold, for nearly all taxpayers this is a distinction without a difference. For the 2024 ROAM Index, this distinction has been eliminated for scoring purposes.

We also harmonized and updated scoring between filing and withholding thresholds this year. We are no longer attempting to translate wage thresholds to day thresholds based on median incomes in each state, as the median income of all workers is not necessarily reflective of the median income for mobile workers. Additionally, wage thresholds were graded more “on a curve” last year due to the lack of states with day-based filing thresholds. However, as more states are beginning to implement day-based filing thresholds, this “curve” is no longer as useful for reflecting the differences between states.

For 2024, the scoring of filing thresholds is as follows:

- 0 points: No threshold at all or global wage threshold. No threshold requires taxpayers to file in a state from the first dollar they earn in that state. Global wage thresholds that look at the total income a taxpayer earns, not just income earned in-state also receive a score of zero points this year, as the vast majority of wage earners will still have to file in a state from the first dollar they earn in that state. As such, there is a significant gap between the score this type of threshold and even a low state-sourced wage threshold earns.

- 0.5 points: Very low state-sourced wage threshold, or a filing threshold set at lower than $1,000 in state-sourced income. Thresholds at this level provide minimal protection to taxpayers against filing obligations in the most frivolous of circumstances from a revenue perspective.

- 1 point: Low state-sourced wage threshold, or a filing threshold set between $1,000 and $2,499 in state-sourced income. Thresholds at this level provide some protection to taxpayers, but the amount is dependent on the taxpayer’s income and is more complicated for taxpayers to determine.

- 2 points: Medium state-sourced wage threshold/low defined-day threshold, or a filing threshold set between $2,500 and $9,999 in state-sourced income, or from the 2nd to the 6th day spent working in that state. Thresholds at this level should protect most taxpayers working a week in a state from filing obligations.

- 3 points: High state-sourced wage threshold/medium defined-day threshold, or a filing threshold set higher than $10,000 in state-sourced income, or from the 7th day to the 20th day spent working in that state. Thresholds at this level should protect most taxpayers working a few weeks in a state from filing obligations. This is the highest score a state can receive for a wage-based threshold.

- 4 points: High state-sourced wage threshold, requiring taxpayers to file in-state from the 21st day to the 30th day spent working in that state. High thresholds provide substantial protection to taxpayers, but fall just short of the gold standard.

- 5 points: Defined >30-day threshold, requiring taxpayers to file in-state only after they work more than 30 days in-state, not counting equivalent days worked on the basis of a wage threshold. This is the gold standard that all states should aspire to.

Montana and Indiana Join States With Day-Based Filing Thresholds

While last year there was only one state (Maine) with a day-based threshold applying to taxpayers in all other states, two states now exempt nonresident taxpayers from individual income tax filing obligations until they work more than 30 days in the state: Montana and Indiana.

“Key Employee” and Similar Carve-outs Penalized

Three states (Montana, North Dakota, and Utah) do not allow their filing thresholds to apply to “key employees.”[1] North Dakota and Utah are penalized for this restrictive and arbitrary carve-out with a 30 percent deduction to their score in this section.

Montana’s definition of “key employee” is less restrictive, applying only to employees earning more than $500,000. Nevertheless, this remains an arbitrary carve-out, and is penalized with a 10 percent deduction to its score in this section.

These same three states do not allow their filing thresholds to apply to construction workers. This is likewise an arbitrary carve-out, which is penalized by a further 10 percent deduction to each state’s score in this section. For example, while Montana would receive a full 10 points for this section due to its threshold of greater than 30 days, it instead receives just 8 points following these deductions.

Mutuality Requirements Penalized

Four states (Louisiana, North Dakota, Utah, and West Virginia) offer day-based thresholds, but only to nonresidents whose state of residence provides a “substantially similar exclusion” or has no individual income tax. These “mutuality requirements” are distinct from “reciprocity agreements” in that their intent is to encourage other states to enact safe harbors of their own. But the practical effect is to limit the benefit of these states’ filing thresholds to residents of just a few other states, a major drawback.

Furthermore, the determination of what comprises a “substantially similar exclusion” is up to each state. For example, it remains unclear to residents of Louisiana whether their state’s 25-day threshold represents a “substantially similar exception” to West Virginia, which has a 30-day threshold. At the same time, it remains uncertain whether a “key employee” or “construction worker” carve-out would render a state’s threshold not “substantially similar.”

To analyze these carve-outs, we used Census commuter data to find what percentage of incoming commuters would be covered by these four states’ thresholds. Each state’s score (after penalties for “key employee” and “construction worker” provisions) is then multiplied by the percentage of incoming commuters who are covered by the state’s threshold.

Louisiana’s threshold, for example, covers over 40 percent of incoming commuters, in large part because its neighbor Texas has no income tax. Its score is reduced far less than West Virginia’s, for example, in which less than 2 percent of incoming commuters, nearly all of whom come from Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, are covered.

If more states pass less restrictive filing thresholds, presumably these mutuality requirements will carve out fewer incoming taxpayers, allowing these states to score higher. Until then, states should reject mutuality provisions until a critical mass of states with filing thresholds exists to place pressure on holdout states.

Three other states introduced legislation in 2023 to institute filing thresholds that would exempt nonresidents from individual income tax filing obligations until they work more than 30 days in the state: Kansas, Minnesota, and Nebraska. Kansas and Minnesota’s bills included mutuality requirements which would have limited their benefit to taxpayers, and did not make it past the introduction stage. Nebraska’s legislation, LB 173, introduced by Sen. Eliot Bostar was eventually folded into the major tax package, LB 754, albeit with some modifications. Unfortunately, provisions relating to nonresident income tax filing obligations were cut from the final version of the bill.

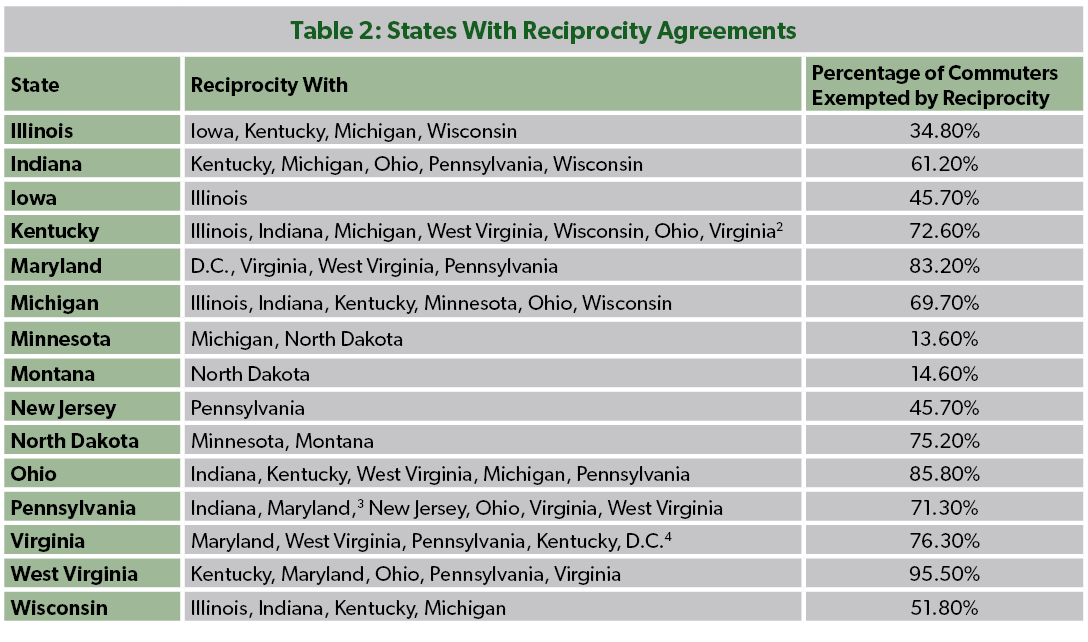

Reciprocity Agreements

Reciprocity agreements are agreements between states to treat taxpayers who live in one state but work in another as working in their state of residence for tax purposes. In other words, a taxpayer residing in Virginia who commutes to a job in Maryland pays income taxes only to Virginia where they live, because the two states have a reciprocity agreement.

Reciprocity agreements are desirable because they greatly simplify state income taxes for affected taxpayers. Absent reciprocity agreements, taxpayers are generally required to file a tax return in both states, then claim a credit for taxes paid to the state their workplace is located in against the taxes owed to their state of residence. Not only is this more complicated than the tax filing process for taxpayers who do not commute across state lines, but it also results in commuting taxpayers paying the higher of the two states’ tax rates.

To model the impact of states’ reciprocity agreements, we use the last release of American Consumer Survey commuting data to see how many workers are exempted by each reciprocity agreement. This data has recently been updated for 2016-2020, providing a more up-to-date picture of how many workers are exempted by each reciprocity agreement. States are then ranked on a ten-point scale on what percentage of commuters into the state are exempted from filing taxes to that state due to reciprocity agreements. A state exempting 100 percent of its workers would receive a 10/10, while a state exempting 52 percent of its workers would receive a 5.2/10, and so on.

No state protects 100 percent of incoming commuters via reciprocity agreements, though the District of Columbia effectively does so by not imposing tax obligations on nonresidents. West Virginia comes the closest, exempting over 95 percent of incoming commuters due to having reciprocity agreements with each of its five neighbors.

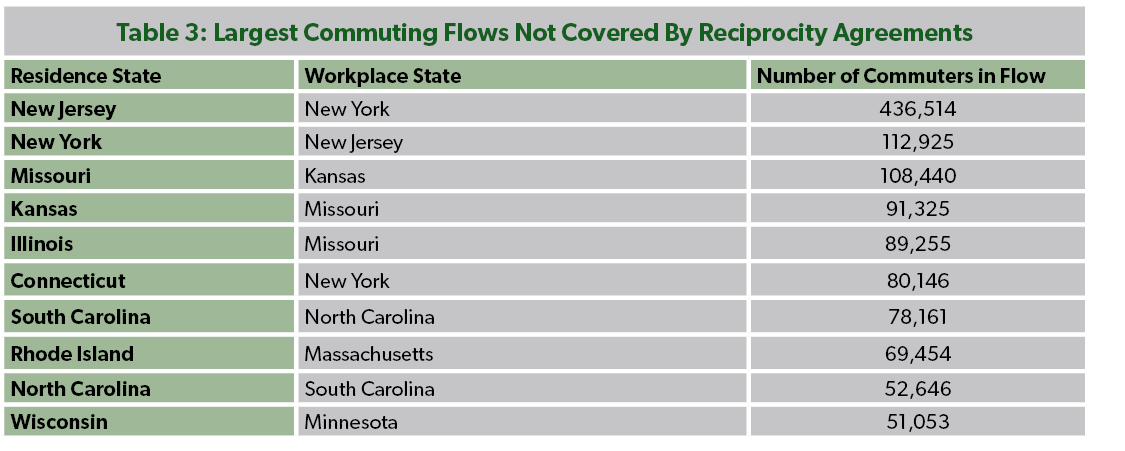

All told, 30 percent of commuters traveling into states with an individual income tax are exempted from individual income tax obligations in that state by a reciprocity agreement. The ten largest commuting flows not covered by reciprocity agreements, not counting those including states with no individual income taxes, are shown below.

States are, understandably, more willing to enter into reciprocity agreements when the commuting flows are roughly equal in each direction. States will always find it easier to pursue good tax policy and simplification for their taxpayers when the foregone revenue from doing so is minimal. Of course, this is why reciprocity agreements are unlikely when flows are lopsided or one state has no income tax — such as with the large commuting flow from New Hampshire to Massachusetts.

While this explains why a state like New York has taken a combative stance in tax disputes with its neighbors like New Jersey and Connecticut, it makes the inaction of high-traffic state pairs like Missouri and Kansas or Wisconsin and Minnesota to enter into reciprocity agreements all the more baffling. After all, states like Illinois and Indiana have managed to maintain long-running reciprocity agreements even as more than twice as many Hoosiers commute into Illinois as Illinoisans into Indiana.

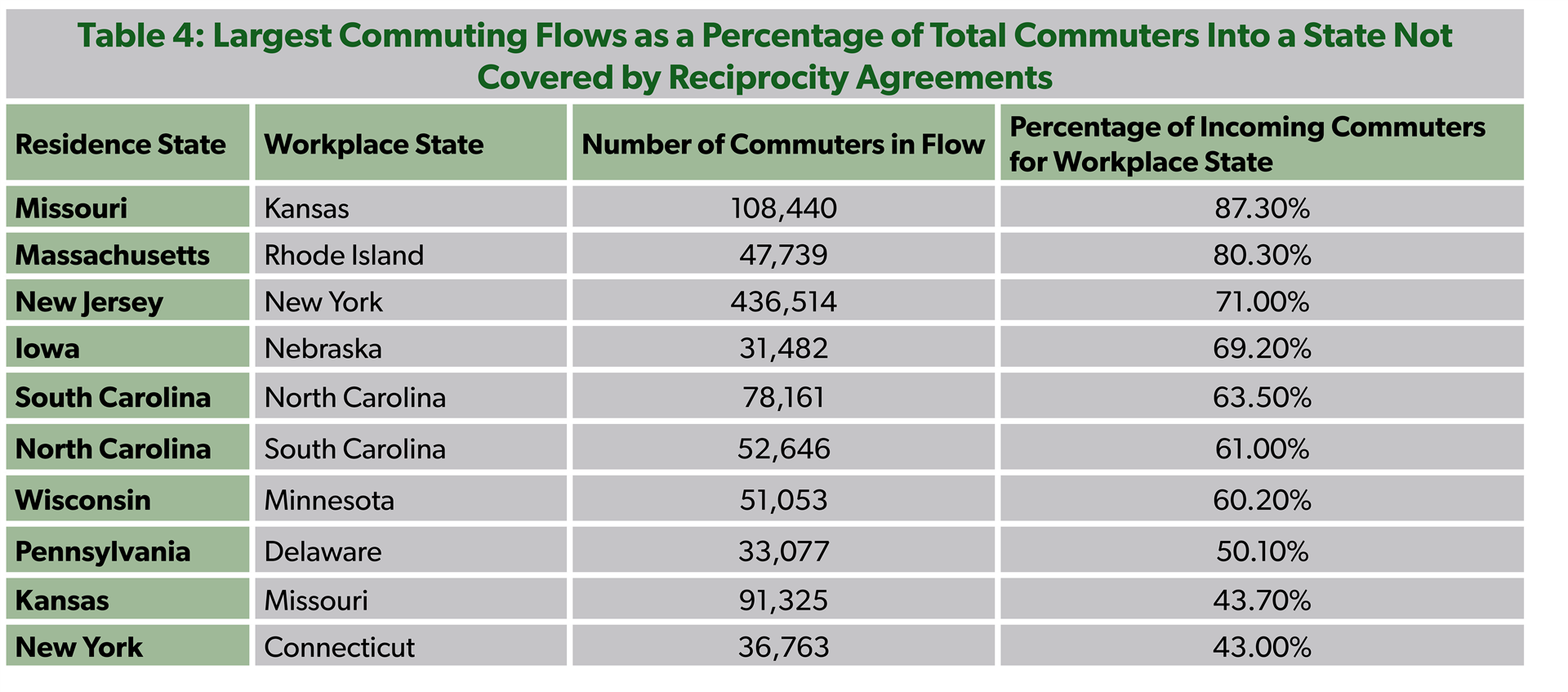

These figures represent the largest commuting flows in terms of raw numbers, but some states have a clear opportunity to exempt a large percentage of incoming commuters with a single reciprocity agreement. Below are the commuting flows not covered by reciprocity agreements that represent the largest percentage of incoming commuters into a state — in other words, the clearest opportunities for states to pursue productive reciprocity agreements. Once again, commuting flows between states where one state has no individual income tax are not included here.

To improve in this category, states should enter into reciprocity agreements with neighboring states, particularly neighbors that have the highest commuter traffic into their state. Policymakers can also authorize their Departments of Revenue with statutory authority to enter into bilateral agreements, or they can extend unilateral offers of reciprocity to any state that provides the same treatment in return, as Indiana, Minnesota, and Wisconsin do.

Indiana’s version of this unilateral offer has proven the most effective, as a dispute over a revenue-sharing agreement between Minnesota and Wisconsin led to a cancellation of the two states’ reciprocity agreement in the past. These two states now, despite each theoretically extending such a unilateral offer of reciprocity, do not currently have reciprocity with each other in the fallout of the failure of this revenue-sharing dispute.

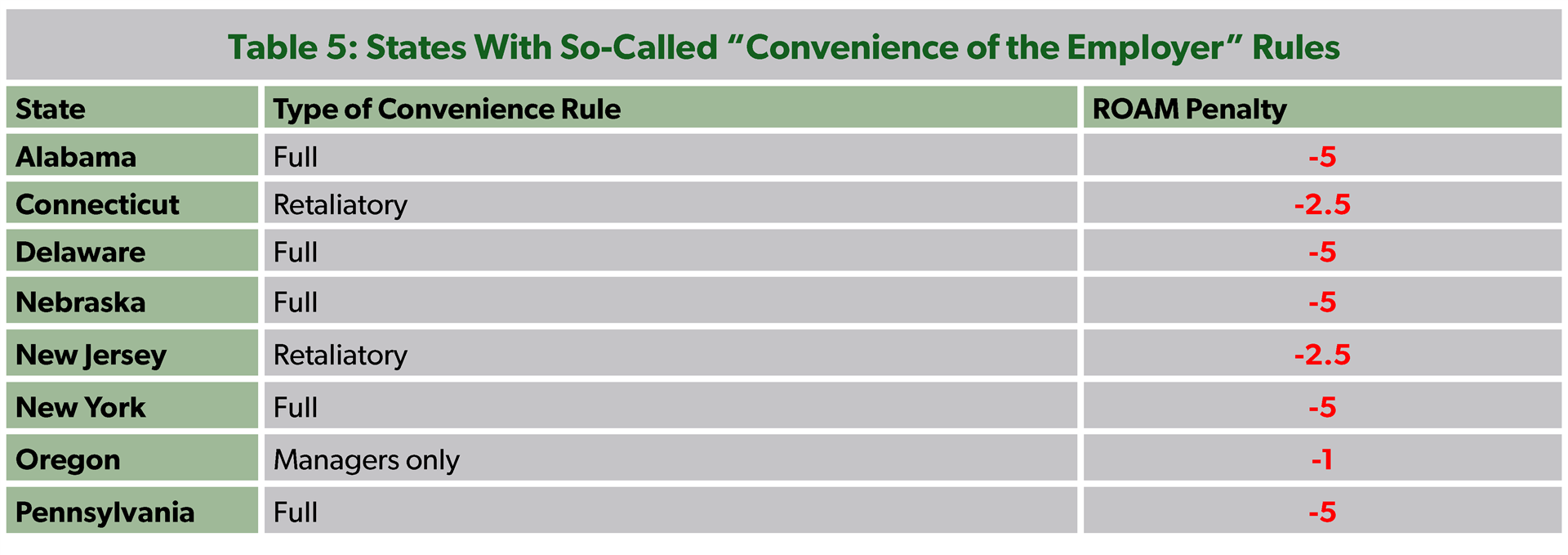

So-Called Convenience of the Employer Rules

“Convenience of the employer” rules are requirements that taxpayers who live and work in another state must nevertheless pay income taxes to their employer’s state, even if they may never physically set foot in it. The term comes from New York, which imposes such a rule on employees of in-state companies unless the taxpayer proves to New York officials that working remotely is a necessity, not merely a “convenience.” Taxpayers rarely win.

For example, a New Jersey resident commutes from New Jersey to an office in New York City. Growing tired of the long commute, the New Jerseyan receives permission from their employer to switch to remote work from their New Jersey home. Because New York has determined that avoiding a commute is merely “convenience,” New York requires the taxpayer to continue paying New York income taxes.

Convenience of the employer rules are fundamentally illogical and cause significant confusion. These rules are also particularly harmful because they can result in double-taxation. Generally, when a taxpayer is required to file taxes in two states, they can receive a credit against taxes paid to one of the states, thereby avoiding being taxed by two states on the same income. However, when a high-tax state like New York claims the power to tax the income of a taxpayer who lives and works in another state, there is the risk of the taxpayer being caught in a tug-of-war between the two states, risking double-taxation.

Five states impose full-fledged convenience of the employer rules: Alabama, Delaware, Nebraska, New York, and Pennsylvania.[5] Alabama joined this group in 2023 following an Alabama Tax Court decision effectively judicially imposing a convenience of the employer rule.[6] Each of these four states earns a flat -5 point penalty to their overall score.

Another state moved in the wrong direction in this area as well. Connecticut had already imposed a retaliatory version of the convenience of the employer rule that applies only to residents of states that impose their own convenience rules. This past year, New Jersey joined Connecticut by legislatively imposing a retaliatory version of this rule of its own. While retaliation against “convenience” states is understandable, taxpayers are ultimately the ones hurt. Consequently, Connecticut and New Jersey earn a penalty of -2.5 points.

Oregon’s version of the convenience of the employer rule, while not new, is also being scored this year. Oregon imposes a convenience of the employer rule, but only against nonresidents performing managerial functions. This arbitrary yet limited rule likewise earns a penalty of -1 points.

Nebraska very nearly struck a major blow to its convenience of the employer rule this past year. LB 416, introduced by Senator Kathleen Kauth, would have restricted the convenience rule to taxpayers who spent more than 30 days physically working in the state. While this would have been a major improvement on the status quo, it would have continued to apply the convenience of the employer rule in some circumstances. Sen. Kauth’s legislation was eventually folded into the aforementioned tax package, LB 173, though it too was cut out before the final package was signed by the Governor.

Individual Income Tax Code

While it is not the most important factor in considering a state’s friendliness to remote and mobile workers, it is worth considering how burdensome it is to be caught in each state’s tax net. As such, the ROAM Index does consider a state’s individual income tax code as part of its score.

To do this, we borrow from the 2024 Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index (SBTCI), specifically the individual income tax component. Under the SBTCI’s individual income tax component, each state receives a score out of ten points that considers rates, structure, deductions, inflation indexing, and tax treatment of married couples, among other factors.

The SBTCI’s individual income tax component is on a 10-point scale, but is only half-weighted. States receive their SBTCI individual income tax component score out of five points.

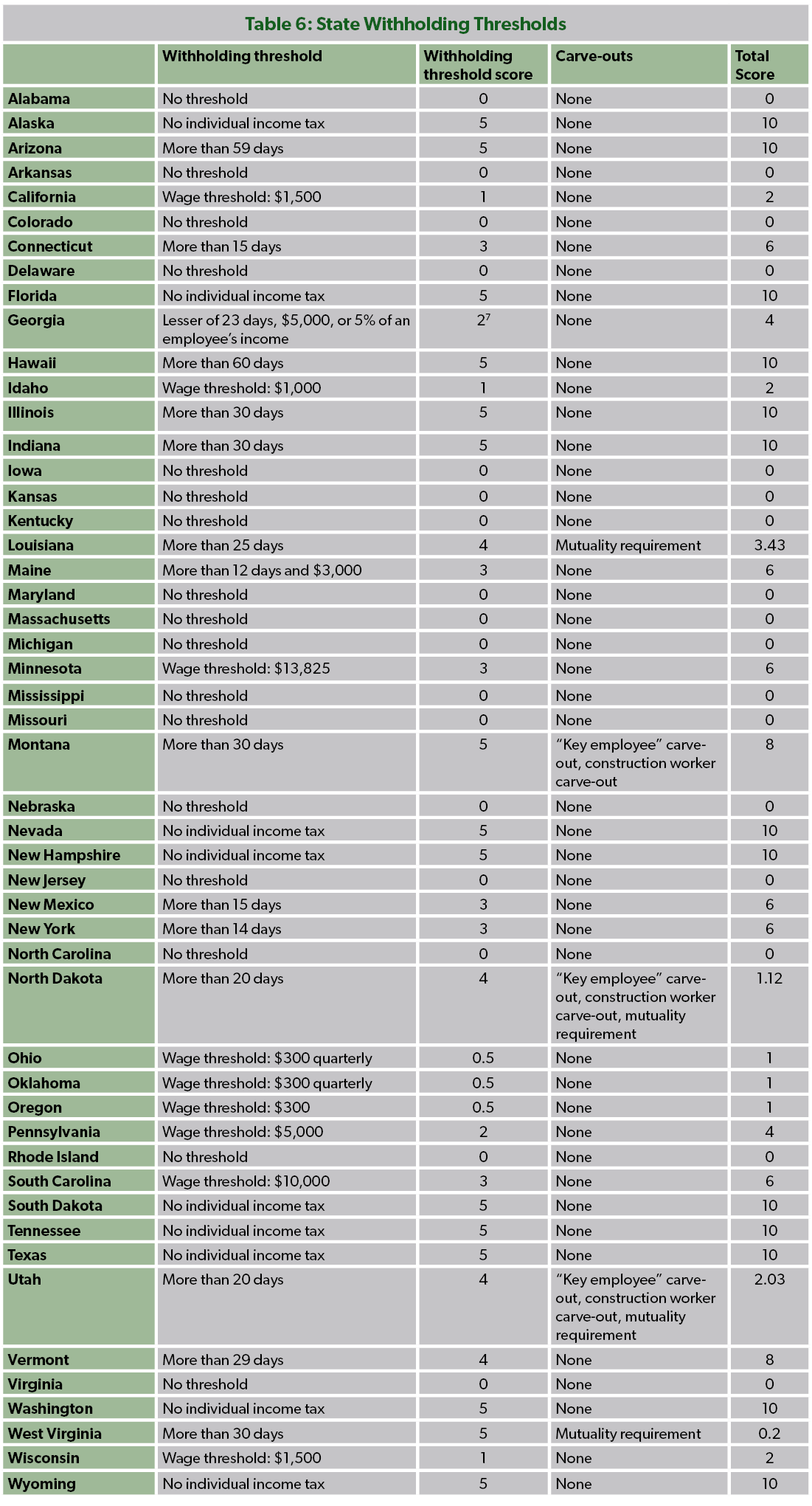

Withholding Thresholds

Only one factor in the ROAM Index directly measures business burdens, but it is one that is very impactful for small and medium-sized businesses with employees who travel. Withholding thresholds represent threshold that employees must exceed before a business is required to withhold income taxes on the employee’s behalf. Similar to filing thresholds for individuals, businesses can benefit from thresholds before they must withhold income taxes on behalf of employees earning income in a given state.

On this front, states have made more of an effort to provide relief than on filing thresholds. 24 states have at least some threshold that employees must exceed before their employer is required to withhold individual income taxes on their behalf.

Just like with filing thresholds, day-based thresholds are preferable to wage-based thresholds. Day-based thresholds are far more intuitive and easier to track than wage thresholds, particularly for businesses with multiple employees spending short periods of time working around the country.

As previously mentioned, NTUF has updated its methodology for scoring withholding thresholds and harmonized scoring between filing and withholding thresholds. The scoring system for withholding thresholds is as follows:

- 0 points: No threshold at all. No threshold requires businesses to withhold employees’ income in a state from the first dollar those employees earn and the first day they work in that state.

- 0.5 points: Very low state-sourced wage threshold, or a withholding threshold set at lower than $1,000 in state-sourced income. Thresholds at this level provide minimal protection to businesses against withholding obligations.

- 1 points: Low state-sourced wage threshold, or a withholding threshold set between $1,000 and $2,499 in state-sourced payroll. Thresholds at this level provide some protection to businesses, but the amount is dependent on the employee’s income and is more complicated for businesses to determine.

- 2 points: Medium state-sourced wage threshold/low defined-day threshold, or a withholding threshold set between $2,500 and $9,999 in state-sourced payroll, or requiring businesses to withhold the 2nd to the 6th day that an employee spends working in that state. Thresholds at this level should protect most businesses with employees working a week in a state from withholding obligations.

- 3 points: High state-sourced wage threshold/medium defined-day threshold, or a withholding threshold set higher than $10,000 in state-sourced payroll, or requiring businesses to withhold from the 7th day to the 20th day that an employee spends working in that state. Thresholds at this level should protect most businesses with employees working a few weeks in a state from withholding obligations. This is the highest score a state can receive for a wage-based threshold.

- 4 points: High state-sourced wage threshold, requiring businesses to withhold in a state from the 21st day to the 30th day that an employee spends working in that state. High thresholds provide substantial protection to businesses, but fall just short of the gold standard.

- 5 points: Defined >30-day threshold, requiring businesses to withhold in a state only after an employee works more than 30 days in a state. This is the gold standard that all states should aspire to.

We penalize carve-outs in the five states with them. These carve-outs are identical to those described above in the “filing thresholds” section, and the penalties are largely the same.

The exception is for states with mutuality requirements, which have slightly different impacts given that some states offer “substantially similar” withholding safe harbors but not filing safe harbors. The most impactful example of this affects Utah, as Arizona offers a withholding safe harbor that protects employers with employees working up to 59 days in a state, but no filing safe harbor. This fact means that Utah’s withholding threshold applies to more incoming employees than does its filing threshold.

Table 6: State Withholding Thresholds

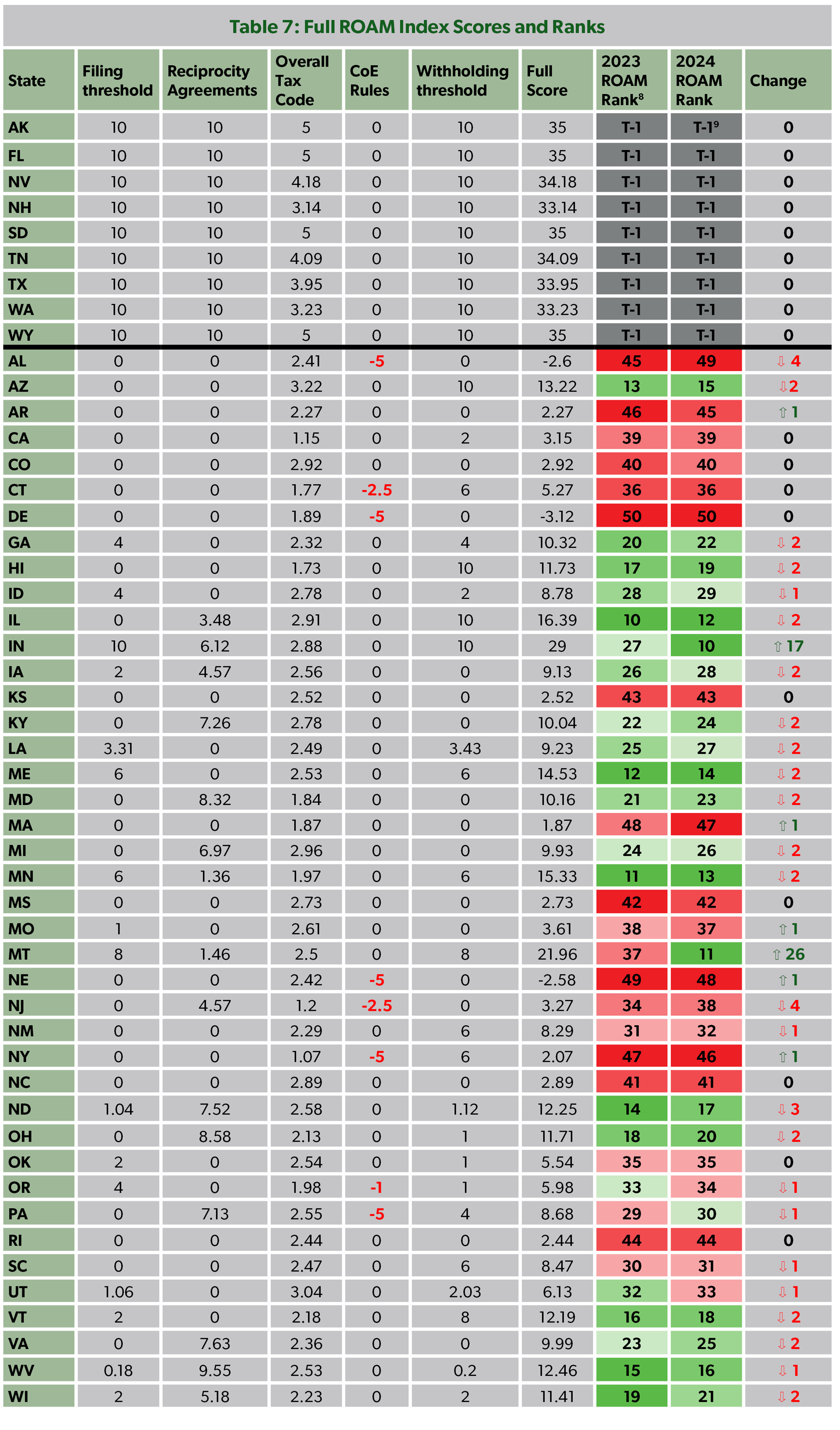

Full ROAM Index Scores and Ranks

All of these scores taken together yields each state’s full ROAM Index score and ranking.

The two biggest risers this year are also the two new highest-scoring states: Montana and Indiana. Both these states passed filing and withholding thresholds of greater than 30 days over this past year, though Indiana separates itself from Montana in not carving out “key employees” or construction workers, as well as in having more impactful and numerous reciprocity agreements. While Montana improved its rank on the ROAM Index the most this past year, Indiana stands apart as the only state having done essentially everything possible to improve its ROAM Index score.

The biggest fallers this year fell primarily due not to policy changes, but rather because of the ROAM Index’s methodological changes. Utah, for example, dropped from 21st to 33rd as a consequence of the ROAM Index’s more strict scrutiny of mutuality requirements.

The biggest faller due to policy changes is Alabama, which dropped from an already-poor 43rd to 49th as a consequence of its newly-implemented convenience of the employer rule.

Conclusion

States cannot keep their heads in the sand and pretend that the economy is not changing. Tax policies play a major factor in residency decisions, and remote work appears to be accelerating preexisting trends of taxpayers moving away from states with punitive tax codes and towards greener pastures. States can either resist the trend and bleed taxpayers, or embrace it and work to become competitive.

State policymakers seeking to make their states more attractive to remote and mobile workers should follow the following principles:

- A > 30-day filing threshold of days worked in-state before taxpayers must file an individual income tax return.

- A > 30-day withholding threshold of days an employee must work in-state before their employer is required to withhold income taxes on their behalf.

- Mutual reciprocity agreements with neighbors to provide certainty and simplicity to commuting taxpayers.

- No “convenience of the employer” rules that require taxpayers to pay income taxes to a state that they do not physically work in.

For a state-by-state rundown of ways to improve, we have broken down each state and what it can do to better its tax code’s treatment of remote and mobile workers.

States scoring poorly on the ROAM Index should take it as a wake-up call that they are at risk of shutting themselves off from a digitizing economy. Remote work brings change, and change brings winners and losers. States refusing to modernize their tax codes to attract the remote work migration are in danger of becoming the latter.

[1] North Dakota and Utah follow the federal definition of “key employee,” which includes:

- All employees making more than $215,000 for 2023 (adjusted annually for inflation),

- Business owners holding more than 5 percent of their business’s stock or capital,

- Business owners holding more than 1 percent of their business’s stock or capital and earning more than $150,000 (not inflation-adjusted)

[2] Virginia residents must commute daily to Kentucky to be covered by the state’s reciprocity agreement with Kentucky.

[3] Maryland does not extend reciprocity to Pennsylvania residents of local jurisdictions that impose income tax on Maryland residents. This is not accounted for in the percentage reported here.

[4] Kentucky and D.C. residents must commute daily to Virginia to be covered by their state’s reciprocity agreement with Virginia.

[5] It is worth noting that “convenience of the employer” rules often come about without any legislative direction whatsoever, being first applied by overzealous revenue departments. Preemptively clarifying the definition of taxable income for individual income tax purposes to clarify that only income earned while the taxpayer is physically present in the state is taxable is therefore a worthwhile exercise even for states that do not currently impose any form of “convenience of the employer” rule.

[6] Mark E. Bollinger v. State of Ala. Dep't of Rev., Inc. 22-390-LP (Ala. Tax Tribunal, 3/8/23)

[7] Georgia has a 23-day threshold, which would earn a 4 in this category, but Georgia’s safe harbor no longer applies if the employee earns more than $5,000 in Georgia-sourced income or more than 5 percent of their total income. Consequently, the lowest-scoring threshold of $5,000 is used.

[8] 2023 ROAM ranks are calculated using updated methodology, and consequently are different than those included in last year’s report.

[9] All the states with no individual income tax are tied for first place.