Authored by Leah Vukmir, Jess Ward, Mattias Gugel, and Andrew Wilford.

(pdf)

JUMP TO:

Why take the time to study the payroll tax?

As nearly 93 percent of Americans are now using direct deposit to receive their paychecks from their employers, taxpayers aren’t explicitly seeing their paystub and the breakdown of where exactly their income goes every two weeks or monthly anymore.

The ease and automatic nature of being paid by direct deposit can indeed be a convenience. However, this leaves many taxpayers and policymakers needing to be made aware of how much employees make and how much they pay in taxes compared to how much money is put into their bank accounts. In fact, according to the American Payroll Association’s “Getting Paid in America” report, just over 3.5 percent of Americans get a paper check as their primary payment method.

While much of the conversation about reducing taxes for earners revolves around the state income tax and much-needed efforts to flatten or eliminate those taxes, people often overlook payroll taxes for the substantial burden they place on employees and employers. Even those highly attuned taxpayers who know the amount of their contributions to the payroll tax may not be aware that employers often have matches they pay at the expense of higher earnings for the employee or that businesses simply decide not to hire additional employees because of the financial burden of taxes.

Known most often for the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes that fund federal programs such as Social Security and Medicare, payroll taxes also have significant state policy implications ranging from state unemployment insurance programs to new programs being created or expanded, such as paid family leave efforts.

This National Taxpayers Union Foundation (NTUF) report aims to provide you with a general review and understanding of the payroll tax, show some case studies of what’s working in states and what needs updating, and provide policy reform recommendations to help policymakers ensure these taxpayer dollars are put to prudent fiscal stewardship.

Let’s start. What is the payroll tax?

The Social Security Act of 1935 was enacted by the 74th Congress and signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Driven by the impact of the Great Depression, the policy effectively created Social Security benefits and insurance against unemployment. The Supreme Court upheld the act in two major cases (Helvering vs. Davis & Steward Machine Co. vs. Davis) in 1937.

Payroll taxes fund these entitlement programs, and over the following decades, payroll taxes would evolve into the second-largest portion of the federal budget. In 1965, Congress and President Johnson amended the Social Security Act, establishing Medicare and Medicaid.

Payroll taxes would evolve and inevitably fund massive federal programs such as Social Security and Medicare, and state payroll taxes would be known for funding Unemployment Insurance (UI).

And what is Unemployment Insurance?

To begin understanding the effect of the payroll tax on states, we must start with the most extensive state program funded by this tax — Unemployment Insurance.

Initially created in 1935, the unemployment insurance program was intended to further various entitlement and societal goals. Fundamentally, the program provided a temporary source of income, financed by employers, for workers laid off from their jobs at no fault of their own.

The federal unemployment insurance law underlies the unemployment insurance systems developed by each state. This law — primarily originated in the Federal Unemployment Tax Act and portions of the Social Security Act — was adopted to persuade states to establish their own unemployment insurance systems and to ensure that states met minimum standards. This state-driven system makes unemployment insurance vastly different from other payroll tax-funded programs like Social Security and Medicare, which are entirely run and administered by the federal government.

A little history…In 1932, Wisconsin would be the first state in the nation to implement an unemployment insurance program. Three years later, Congress approved a national unemployment insurance policy modeled after the Wisconsin program as part of the Social Security Act of 1935. The nation's first unemployment benefits check in the amount of $15 was issued on August 17, 1936, by the Industrial Commission of Wisconsin to Neils B. Ruud, a laid-off employee left jobless by the Great Depression. The program was implemented to encourage stable employment practices while providing an economic safeguard during downturns. |

Today, all 50 states have unemployment insurance systems. Federal law serves primarily to maintain specific standards or to provide financial assistance to an individual state’s program.

The most significant component of the federal unemployment insurance law is the federal unemployment tax, collected via the payroll tax. The tax is paid by most private, for-profit employers and assessed on the first $7,000 per year paid to each employee for work covered by the federal unemployment insurance law.

The Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) tax is 6 percent of the first $7,000 of employee earnings. Federal law provides a maximum of 5.4 percent credit for state unemployment insurance taxes paid. This credit is available to employers where the state unemployment insurance law conforms to federal law, with state tax rates being experience-rated.

The federal government’s revenues from the federal unemployment tax have three primary purposes:

They finance the administration of the unemployment insurance system and job service program at the federal and state levels. To receive this funding, states must have their unemployment insurance law approved by the U.S. Department of Labor Secretary.

Federal unemployment tax revenues finance the federal share of extended benefit payments under federal supplemental and emergency programs.

These revenues also finance loans to states' unemployment insurance trust funds that require advances to meet benefit obligations.

Federal law requires state unemployment insurance systems to cover nonprofit organizations and government entities. In addition, state unemployment insurance tax collections are deposited in the federal unemployment trust fund of the U.S. Treasury and credited to individual state trust fund accounts. States then draw on these accounts to make unemployment insurance benefit payments and financially assist the unemployed.

While the initial goals are still the system’s foundation, the scope has increased considerably since implementation. The current program comprises interrelated benefit and tax structures, which state and federal policy provisions affect.

What does the federal government use payroll taxes for?

In the broadest sense, the U.S. government uses payroll taxes for two large programs, Social Security and Medicare, and these federal payroll taxes make up 30 percent of the federal revenue. The federal payroll tax also funds the administration and federal regulation of state Unemployment Insurance programs.

What is Social Security, and how is it funded?

The portion of Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) payroll taxes dedicated to Social Security is used to fund Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance programs, which provide income monthly to retirees, their dependents, and disabled people. Payroll taxes are the primary funding source for those programs, accounting for 89 percent of all revenue in the trust funds.

In 2022, Social Security received nearly $1 trillion in revenue from payroll taxes, up to 4.3 percent of gross domestic product. The remainder of the program’s funding comes from taxation on Social Security benefits and interest gained on trust fund balances. (It is essential also to note that the revenues from payroll taxes into the federal government are not enough to cover the costs of Social Security and other entitlement programs, and the high costs of these spending promises to taxpayers are driving forces behind federal deficits and the federal debt.)

Employers and employees each pay 7.65 percent of their payroll in FICA taxes; the portion dedicated to Social Security is 6.2 percent, and the government levies this tax only up to a maximum income level determined annually.

Self-employed individuals also contribute to these funds through Self-Employment Contributions Act (SECA) taxes. The rates for SECA taxes are identical to those for FICA taxes, with the only difference being that the individual is responsible for paying both the employee and employer portions of the tax.

The Social Security payroll tax only applies up to a certain amount of a worker’s annual earnings. People often refer to that limit as the taxable maximum or the Social Security tax cap. For 2023, the maximum earnings subject to the Social Security payroll tax was $160,200, an increase of $13,200 from 2022.

In 1937, the Social Security tax rate was initially set at 1 percent of taxable earnings, gradually increasing. The current rate of 6.20 percent was established in 1990, although it has been modified twice in response to poor economic conditions. In 2011 and 2012, federal lawmakers temporarily lowered the employee rate to help reduce financial hardships following the recession. The second modification resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic when employees were allowed to defer withholding their share of payroll taxes for Social Security from September 1, 2020, through December 31, 2020. However, had an employee elected to defer paying their portion of the tax, employers would be required to withhold prior deferred taxes from future wages once the option to withhold paying was no longer available.

What is Medicare, and how is it funded?

The Medicare tax was established in 1966 as a federal payroll tax that covers a portion of medical care for seniors 65 or older. When combining taxes collected from self-employed individuals with employer and employee payroll tax portions, approximately $350 billion is paid annually into Medicare taxes. This provides more than 60 million seniors and those with disabilities access to hospitals, specialized nursing, and hospice care. By and large, all U.S. workers must pay Medicare tax on their earned wages.

The tax is grouped with Social Security together under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) and Self-Employed Contributions Act (SECA) taxes.

The Medicare tax is a two-pronged tax that mandates employees have an automatic deduction removed from their paycheck, with the employer contributing the other half of the tax. The tax is based on "taxable wages," a calculation using gross pay and subtracts pretax deductions such as medical insurance, dental insurance, vision coverage, or health savings accounts. Employers must collect the tax and send both the employee and employer portion to the IRS through regular electronic deposits.

Unlike Social Security, all taxable employment income is subject to the Medicare payroll tax. This includes multiple income types such as salary, hourly wages, overtime wages, accrued time off, eligible tips, and bonuses.

The employee tax rate for Medicare is 1.45 percent — and the employer tax rate is also 1.45 percent, making the total Medicare tax rate percentage 2.9. Only the employee portion of Medicare taxes is withheld from paychecks. The employer is responsible for submitting their part independently, often done quarterly. While there is no wage-based limit for the Medicare payroll tax, in 2013, an additional tax withholding of 0.9 percent was imposed for individuals making $200,000 or more and those filing jointly earning $250,000 or more.

For example, an individual with an annual salary of $100,000 would have a 1.45 percent Medicare tax deducted from their paycheck, approximately equaling $120 each month [($100,000/12) x 0.0145]. The employer would pay an additional $120 monthly on their behalf, totaling $240 contributed to Medicare. Self-employed individuals are responsible for contributing the full 2.9 percent rather than splitting the payroll tax with an employer. Self-employed Americans pay their Medicare tax liability through quarterly estimated payments instead of deductions from their paychecks.

It should be noted that, unlike federal income tax brackets, the 0.9 percent surtax for Medicare was never indexed to rise with inflation. Therefore, more and more workers are exposed to the tax each year.

How did the response to the COVID-19 pandemic change unemployment programs?

In 2020, the world changed in response to the novel coronavirus COVID-19. As businesses shut down, the nation saw immediate demands on the unemployment insurance programs like never before. The COVID-19 pandemic grossly differed from prior U.S. economic downturns, given that systems dealt with initial unemployment claims spiking to max levels in days rather than weeks or months.

In response, federal policymakers adopted sweeping changes in laws under emergency orders and acts of Congress, which significantly affected the payroll tax, altering the implementation and increasing the distribution of unemployment benefits. Many of these policies encouraged states to forgo procedures they had in place to promote good stewardship of payroll tax funds due to the immediate demands plaguing state unemployment programs across the country.

What exactly did the federal government do to increase state unemployment?

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided temporary total federal funding for the first week of unemployment benefits through most of 2020 for states without requiring the typical one-week waiting period. Under The Continued Assistance for Unemployed Workers Act of 2020 ("Continued Assistance Act"), as extended by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), Congress retained this benefit to states through September 2021.

Notably, this federal plan required many states to adjust their guidelines to provide coverage of unemployment benefits for the first week. Many UI programs have a waiting period for these payments to kick in, which were removed in states during the pandemic to receive this federal assistance.

The CARES Act, as subsequently extended by the Continued Assistance Act, also provided federal funding to states to reimburse some nonprofits, government agencies, and Native American tribes for 50 percent of the costs they incurred to pay regular UI benefits from March 2020 through April 2021. ARPA also provided a reimbursement rate of 75 percent of the expenses incurred to pay standard unemployment benefits from April 2021 through September 2021.

Before the CARES ACT, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act ("Families First Act"), signed into law in March 2020, provided emergency administrative grants to states to assist with processing unemployment claims.

Under the Families First Act, emergency administrative grants were distributed to states in two equal allotments if specific unemployment criteria were satisfied:

For the first payment, a state needed to show that standard UI processing, accessibility, and notification systems were ready.

For the second payment, the state had to:

Have a 10 percent increase in initial UI claims over the same rolling quarter in the previous calendar year,

Commit to maintaining and strengthening access to the UI system, and

Show steps to ease eligibility requirements and access to unemployment, including decreasing or lifting work search requirements, eliminating the waiting week period, and not charging employers directly impacted by COVID-19 due to an illness in the workplace or direction from public health officials to quarantine.

What lessons should policymakers learn from how unemployment insurance changed during the pandemic?While policymakers in Washington, D.C., and statehouses across the nation worked to address the stresses put on our nation’s workers during the pandemic by providing unemployment insurance funding and relief to states through additional funding, the pandemic highlighted the long-standing issues facing state unemployment systems. For example, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the number of unemployment payment errors — due to fraudulent payments to ineligible claimants—greatly increased. The Department of Labor oversees state unemployment programs and estimated that these payment errors increased for FY 2020, from a 9 percent error rate to a 19 percent error rate in FY 2021. Perhaps many of these improper payments were unintentional, given the sheer volume of claims state unemployment systems were processing. However, without question, the pandemic exposed a grossly broken and inefficient policy structure. |

For states that qualified to receive both emergency administrative grant allotments under the Families First Act and met the required unemployment thresholds to trigger the extended benefits program, the federal government funded 100 percent of extended benefit payments provided to individuals through March 2021. This federal funding effectively eliminated the requirement that the state cover 50 percent of extended benefit costs as was typically required.

The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program provided an additional 24 weeks of 100 percent federally-funded unemployment benefits to individuals who had exhausted state benefits. The PEUC extended unemployment benefits, and individuals who received these extended benefits could also qualify for Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation and Lost Wages Assistance supplementary payments. PEUC benefits were payable from around April 2020 through September 2021.

The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program additionally expanded coverage to many not typically eligible for unemployment benefits, such as self-employed workers, independent contractors, freelancers, and workers who did not have enough work history to qualify for regular state benefits, as long as their unemployment was related to a COVID-19 shutdown.

The CARES Act also provided that from April 2020 through July 2020, the federal government would give temporary Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) of $600 weekly to any person eligible for state or federal unemployment benefits. The Continued Assistance Act, extended by the American Rescue Plan Act, provided that from the week ending January 2, 2021, through the week ending September 4, 2021, the federal government offered temporary FPUC payments of $300 weekly to any individual eligible for state or federal unemployment benefits. FPUC automatically provided these supplemental payments to individuals collecting regular unemployment benefits and those receiving payments under the PUA, PEUC, work-share, and other federal unemployment insurance programs. The federal government fully reimbursed states for administering the supplement and the supplemental payment.

Finally, in states with a federally-approved work-share program, the CARES Act provided 100 percent federally-funded unemployment benefits through September 4, 2021. Work-share programs provide a prorated unemployment benefit for employees of employers who voluntarily agree with the state to reduce work hours rather than laying off workers.

What else do states use payroll taxes to fund?

Unemployment insurance, however, isn’t the only program that states fund with payroll taxes. Recently, states have begun to employ the payroll tax as a means to fund Paid Family Leave Programs.

The U.S. federal government has a law that requires up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave to care for a newborn or newly adopted child, which applies to businesses with 50 or more employees. However, many states have begun to enact paid family leave to match benefits provided in more progressive European countries.

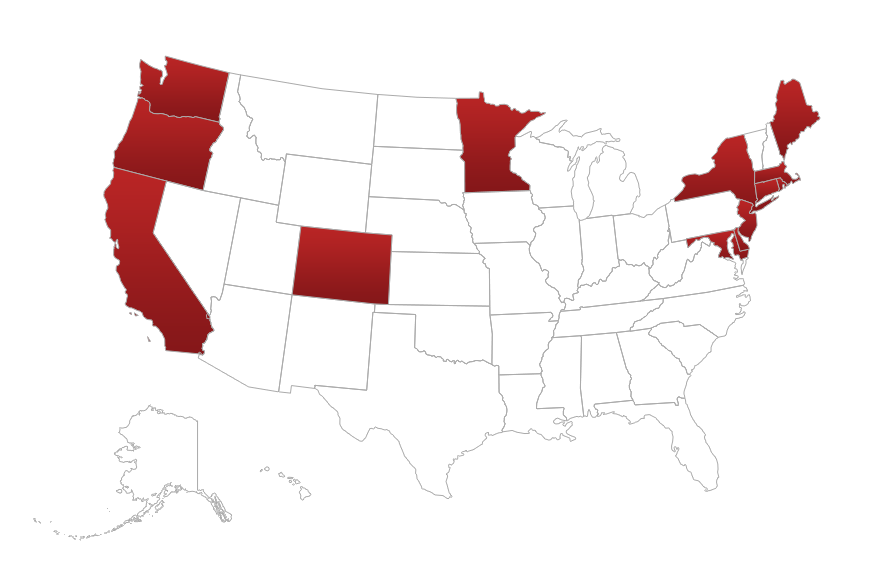

California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Washington, and the District of Columbia have all somewhat recently mandated paid family leave.

States with Paid Family Leave Programs

The cost of these paid family leave programs has yet to be fully known, and to pass and sell many of these programs, policymakers have been shy about the actual costs to taxpayers. Unfortunately, these costs have grown more than initial estimates. For example, the state of Washington didn’t initially collect enough money to cover paid leave requests. Workers ended up using the program more than anticipated. To pay for the increased demand for the leave program, the state had to boost its premium rate twice, from 0.4 percent initially to 0.8 percent in 2023.

Furthermore, unlike the federal government, states do not have those options for printing money, and many are limited in how they can amass debt to underwrite their payroll tax-funded programs, unlike the federal government regarding Social Security and Medicare. So, taxpayers often need to bear the total cost of these entitlement programs immediately, which may often come in the form of increased demand on payroll taxes.

How do payroll taxes impact an individual employee?

U.S. workers, by and large, see two hefty taxes taken out of their paychecks: individual income tax and payroll tax, which are levied on both the employee and the employer. Slightly more than half of the payroll tax burden is paid by employers, but workers ultimately bear much of this burden through reduced wages.

In 2022, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported that the overall tax burden on an average-income single worker in the U.S. was 30.5 percent, including social security contributions. This is lower than the average tax burden on labor for single workers among OECD countries.

The tax burden that the worker faces includes the income tax share of 13.8 percent of pretax income, employee payroll taxes of 7.1 percent, and employer payroll taxes of 7.5 percent.

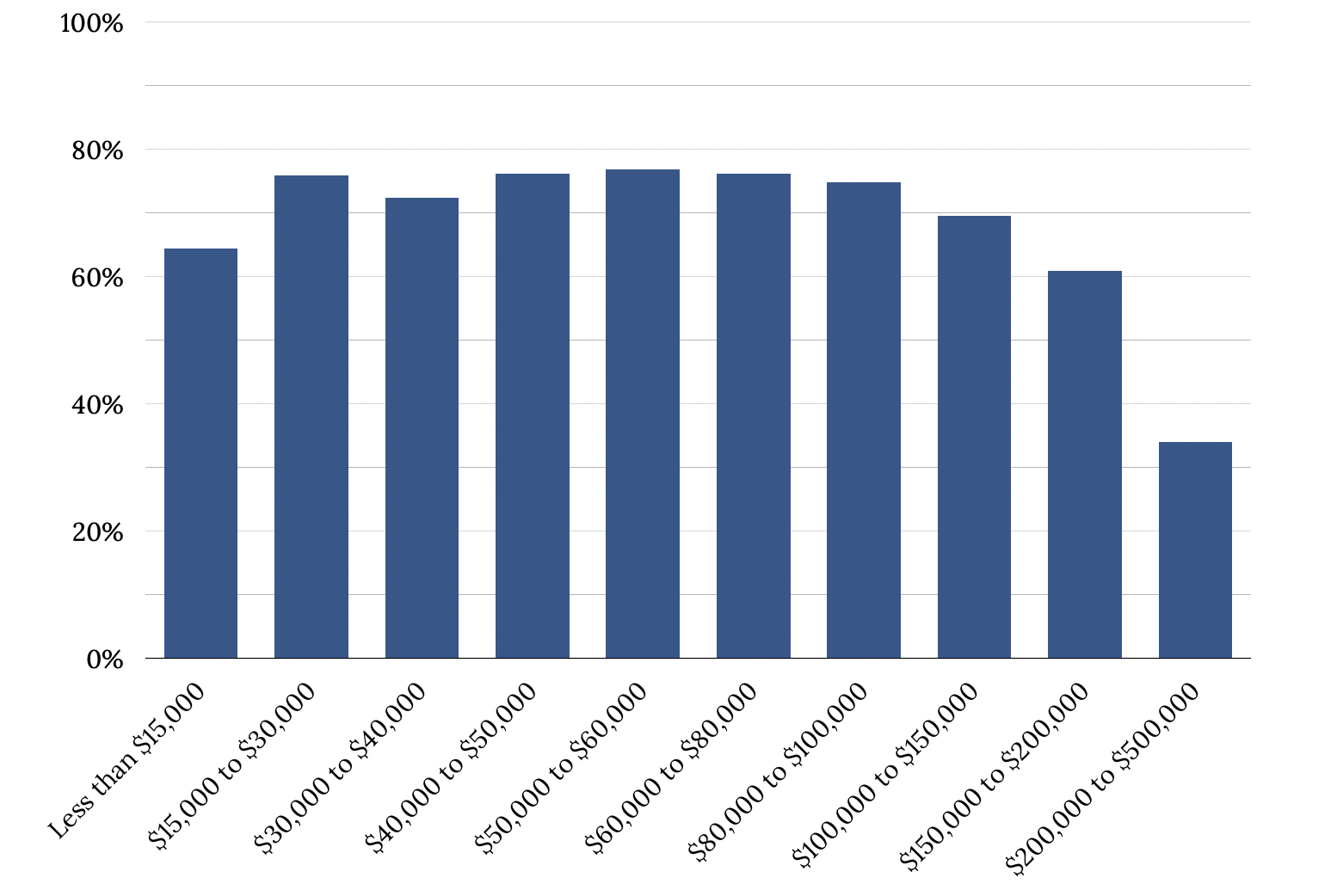

Furthermore, while the conversation around lowering or even eliminating state income taxes is an important one to have, it is also crucial to note that the vast majority of lower- and middle-class taxpayers pay more in payroll taxes than they do for income taxes.

Percentage of Taxpayers Whose Payroll Taxes Are Greater than Income Taxes (Projected)

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation staff estimates for 2023.

Who really pays the employer portion of payroll taxes?

A tactic some policymakers use to sell expansions of entitlement programs, such as new paid leave programs, to the public is to say they are not creating a new tax or employers will be forced to bear the program’s cost. The truth is that they really do plan these increases to the payroll tax on both employers and employees.

Taxpayers must be savvy when listening to these arguments. Even when a program is funded “by the employer,” it comes from their paychecks.

According to a Congressional Budget Office study, about 60 percent of the employer’s portion of the payroll tax comes in lost wages to the employee because of the elasticity of the demand for labor. So, when lawmakers say that paid leave will be funded 50 percent by the employer and 50 percent by the employee, the actual economic cost of that program comes at about 80 percent to the employee [50 percent + (50 percent x 60 percent)].

That 80 percent of the entire portion of this tax workers lose out also doesn’t reflect the lost opportunity costs of improvements in workforce education, capital, or a better employee experience that employers could make if they didn’t have to pay their portion of the payroll tax.

How do payroll taxes affect businesses?

When a business files a tax return each year, it includes a form showing they paid state unemployment taxes, qualifying them for a federal tax credit. The credit can bring the FUTA tax rate down as low as 0.6 percent. The most common state payroll tax pays for state unemployment benefits, of which employers cover 100 percent.

Unemployment insurance is based on what tax agencies call a wage base, a cap on the wages subject to a particular tax. The wage base and tax rates vary by state. Some states collect additional payroll taxes for workforce development, disability insurance, and transit.

Unemployment tax payments for a business coincide with payroll or are separate monthly or quarterly payments, depending on the process set forth by each state.

Along with those tax responsibilities, employers are also responsible for additional benefits based on withholding or administered by a business, such as:

Workers' Compensation Insurance

States set requirements for workers' compensation insurance. What the employer has to pay is usually based on the number of employees, with three employees being a standard minimum threshold.

State disability insurance

California, Hawaii, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Puerto Rico have mandatory disability requirements for employers to support programs that pay a portion of worker wages for work missed due to caregiving or a disability.

Paid leave

If a company offers or the state mandates paid time off for personal days, vacation, sick days, parental leave, or any other purpose, these are recorded as part of the payroll process. Paychecks generally list compensation as part of an employee’s paid leave benefits, even when the employee’s pay is the same as normal.

Health care costs

Companies with more than 50 employees must provide a health insurance plan for employees under the Affordable Care Act. Businesses may also choose to provide a plan if they are smaller employers. At payroll, employers will deduct any portion of the employee’s premiums, and the company will be responsible for the employer portion.

Retirement plan contributions

If a company sponsors an employee retirement plan, the employer will manage contributions with payroll. They’ll deduct employee contributions from their pay and be responsible for any employer match they offer. Some “safe harbor” retirement plans allow employers to reduce paperwork and regulatory burdens and require minimum employer match percentages.

Reimbursements and stipends

If a business offers a stipend (for example, for a home office) or reimbursements (such as those for work-related travel), the employer generally processes those with payroll and includes them with an employee’s paycheck. Income tax rates for reimbursements and stipends differ from those for regular income, so businesses must classify them correctly.

Other benefits

A business will manage other benefits with payroll, as well, including charity matching and deductions, HSA contributions, wellness programs, and other employee benefits. Depending on the benefit, the employer may deduct employee contributions, make payments into an associated account, or include a stipend with the employee’s paycheck.

How do states calculate a business’s unemployment insurance tax rate?

Unlike all other employer tax rates, a State Unemployment Insurance (SUI) tax rate is one over which a business has some control. A low employee turnover rate is critical to keeping an SUI rate manageable.

Businesses with high turnover rates will likely pay a higher rate because SUI liability is partly based on former employees filing for unemployment and receiving benefits — the more employees who make UI claims, the greater the business’ liability.

This tax structure is particularly problematic for new businesses because they haven’t had the opportunity to pay into the unemployment pool used to cover unemployment claims. When a new business has former employees who receive unemployment benefits, the state pays on the company’s behalf and then recoups its money by raising a business’ tax rate. The same is true for companies that historically have a high turnover rate, such as in the service industry, at no fault of their own.

Another way turnover affects overall unemployment tax liability is if an employee leaves halfway through the year (even voluntarily) and the business replaces them with a new hire. Under these circumstances, businesses pay taxes on both employees up to the wage base. However, if the same employee had stayed the whole year, they would have just paid it once. This particular disadvantage of employee turnover also applies to both FUTA and SUTA.

Two components are used to calculate SUTA liability:

A business's assigned SUTA rate is multiplied by wages paid that are subject to SUTA taxes (SUTA subject wages).

This value is created and assigned to businesses by the state agency tasked with UI management in each individual state. The rating is assigned to a company’s federal employee identification number (FEIN). It is meant to collect more SUTA tax from companies who have terminated employees (and cost the state’s UI fund more money in claims) and less from those who have not. SUTA rates are meant to be “experience” based so that SUTA rates (and tax bill) will be higher or lower based on how many unemployment claims have been filed. In addition, each state has different periods for which a business rating may be affected by a claim.

The SUTA experience rate may be affected for employees terminated years ago (and were rehired by someone else) but who have only recently filed an unemployment claim. For example, it may be deemed “unfair” to impact a company’s experience rating for an extended period of claims when the company only employed an individual for a short period of time. In these cases, the rating agency may “look back” and charge all of the claimants' former employers over the last several years, not just the most recent ones.

Each state has a minimum SUTA rate and a maximum SUTA rate applied to employers. The minimum rate is for companies that have long track records of paying wages with few or no unemployment claims from past employees. The state can charge the maximum rate to employers who have a high number of unemployment claims from their former employees. For some employers, even the maximum rate does not cover the cost to the state’s UI claims fund. In those cases, the state UI fund spreads the shortfall by charging a slightly higher rate to all of the other employers in the state.

For employers that do not have an experience rating with the state, a new business rate is established and used until the employer establishes an experience rating. Each state varies regarding the length of time before a rating is assigned. While some states strive to keep SUTA rates lower for new businesses to encourage growth, other states establish higher rates for certain types of industry, like construction or the service industry, which tend to have higher UI claims.

The second factor that affects SUTA tax liability is the amount of wages a business pays and the number of employees it has.

SUTA taxes are charged to a company for each employee for each year up to a maximum wage value (cutoff value) for the employee. Once the employee’s yearly earnings have reached the cutoff value, earnings for the employee for that year no longer are included in determining the SUTA subject wages.

This cutoff value is known as the state wage base. Each state has different values for the wage base used to calculate SUTA. To recap: SUTA subject wages are the total of all wages paid to each employee up to the wage base in the calendar year.

What is the wage base limit in each state?

State | Wage Base Limit | Employer Rate | Min Rate for Positive Based Employers | Max Rate for Negative Based Employers |

Alabama | $8,000 | 2.70% | 0.14% | 5.40% |

Alaska | $47,100 | Based on industry average for employer | 1.00% | 5.40% |

Arizona | $8,000 | 2.00% | 0.07% | 18.78% |

Arkansas | $7,000 | 3.10% | 0.30% | 14.20% |

California | $7,000 | 3.40% | 1.50% | 6.20% |

Colorado | $20,400 | 1.70% | 0.75% | 10.39% |

Connecticut | $15,000 | 3.00% | 1.90% | 6.80% |

Delaware | $14,500 | 1.80% | 0.30% | 8.20% |

Florida | $7,000 | 2.70% | 0.10% | 5.40% |

Georgia | $9,500 | 2.64% | 0.04% | 8.10% |

Hawaii | $56,700 | 4.00% | 1.20% | 6.20% |

Idaho | $49,900 | 0.80% | 0.17% | 5.40% |

Illinois | $12,960 | *3.525% | *0.725% | 7.63% |

Indiana | $9,500 | 2.50% | 0.50% | 9.40% |

Iowa | $36,100 | 1.00% | 0.00% | 7.00% |

Kansas | $14,000 | 2.70% | 0.17% | 6.40% |

Kentucky | $11,100 | 2.70% | 0.23% | 8.93% |

Louisiana | $7,700 | 1.21% - 6.20% | 0.09% | 6.20% |

Maine | $12,000 | 1.97% | 0.00% | 5.47% |

Maryland | $8,500 | 2.30% | 1.00% | 10.50% |

Massachusetts | $15,000 | 1.45% | 0.56% | 8.62% |

Michigan | $9,500 | 2.70% | 0.06% | 10.30% |

Minnesota | $40,000 | Based on industry average for employer | 0.10% | 8.90% |

Mississippi | $14,000 | 1.00% | 0.00% | 5.40% |

Missouri | $10,500 | 2.51% | 0.00% | 9.77% |

Montana | $40,500 | 1.00% - 2.20% | 0.00% | 6.12% |

Nebraska | Tier 1: $9,000 Tier 2: $24,000 | 1.25% | 0.00% | 5.40% |

Nevada | $40,100 | 2.95% | 0.25% | 5.40% |

New Hampshire | $14,000 | 2.70% | 0.10% | 8.00% |

New Jersey | $41,400 | 3.10% | 0.60% | 6.40% |

New Mexico | $30,100 | 1.00% | 0.33% | 5.40% |

New York | $12,000 | 4.03% | 2.03% | 9.83% |

North Carolina | $29,600 | 1.00% | 0.06% | 5.76% |

North Dakota | $40,800 | 1.13% | 0.08% | 9.97% |

Ohio | $9,000 | 2.70% | 0.80% | 10.30% |

Oklahoma | $25,700 | 1.50% | 0.30% | 9.20% |

Oregon | $50,900 | 1.98% | 0.58% | 5.40% |

Pennsylvania | $10,000 | 3.82% | 1.42% | 10.37% |

Rhode Island | Tier 1: $28,200 Tier 2: $29,700 | 0.88% | 0.89% | 9.49% |

South Carolina | $14,000 | 0.39% | 0.00% | 5.40% |

South Dakota | $15,000 | 1.20% | 0.00% | 9.30% |

Tennesee | $7,000 | 2.70% | 0.01% | 10.00% |

Texas | $9,000 | Greater of 2.7% or average industry rate | 0.23% | 6.23% |

Utah | $44,800 | Varies based on industry | 0.30% | 7.30% |

Vermont | $13,500 | Range from 1% to 4%, based on industry classification | 0.40% | 5.40% |

Viriginia | $8,000 | 2.73% | 0.10% | 6.20% |

Washington | $6,700 | Based on industry average for employer | 0.20% | 6.00% |

West Virginia | $9,000 | 2.70% | 1.50% | *8.50% |

Wisconsin | $14,000 | 3.05% - 3.25% | 0.00% | 12.00% |

Wyoming | $27,700 | Based on industry average for employer | 0.09% | 8.62% |

Where has there been fraud in state unemployment programs recently?

In May 2020, Washington state unemployment officials recovered $300 million in stolen money claimed by scammers instead of those needing unemployment benefits. The agency suspended unemployment benefits payments for two days because of the significant rise in fraudulent compensation claims.

Many Washington residents in need of benefits were caught up in the fraud directly, which involved a scam where criminals, many of them out of state, stole personal information from Washington state residents and third parties to file for unemployment benefits. Criminals sought to capitalize on a flood of legitimate unemployment claims by sneaking in fraudulent claims during the pandemic.

State officials hinted at the scope of the damage done, citing hundreds of millions of dollars but being unable to provide an exact dollar amount of funds that would remain unrecovered. Federal authorities have said that a West African fraud ring is primarily to blame, using identities from prior data breaches. According to the Seattle Times, between March and April of 2020, the number of fraudulent claims for unemployment benefits jumped 27-fold to 700. The story also noted that the department’s fraud hotline was so inundated with calls that it was forced to shut down, temporarily exacerbating the number of fraud claims.

In Rhode Island, WPRI reported in May of 2020 that the state’s Department of Labor and Training had received hundreds of complaints of UI fraud and that the number of purportedly fraudulent accounts was keeping pace with an unprecedented number of legitimate claims for unemployment insurance.

Other states like North Carolina, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Wyoming, and Florida have also been victims. They and federal authorities are trying to claw back as much as possible, but much of the UI fund will be permanently lost. States have also moved to block hundreds of millions more from being paid out, but Washington state's experience indicates how pervasive the fraud issue truly is.

Of course, obtaining precise data from government officials on the size of the UI fraud problem in states is difficult. In a report released in January, the GAO noted that “when looking at known fraudulent activity, the Department of Labor (DOL) reported at least $4.3 billion based on formal determinations of fraud by states. Another $45 billion in UI applications was flagged by the DOL’s Office of Inspector General as potential fraud.”

The DOL estimates about $8.5 billion in UI fraud in 2021, which does not count additional pandemic-related payments. “If the fraud rate found for regular UI applied across all UI programs during the pandemic, it would suggest at least $60 billion in fraudulent UI payments,” the GAO notes.

Another gauge of fraud the DOL tracks is the “improper payment rate.” According to the department’s estimates for the 2022 reporting period, the UI program had an improper payment rate of 21.52 percent nationwide. Many states have much higher levels. Florida, for example, has posted a nearly 40 percent improper payment rate over the last three years.

The pandemic may have peaked, but fraud remains systemic. According to the Internal Revenue Service, states have “experienced a surge” in fraudulent UI claims “filed by organized crime rings using stolen identities.”

Notably, while UI benefit payout rules can be evaded at relatively high levels, payroll tax evasion is far less prevalent. According to criminal enforcement data from the IRS, investigations into payroll tax abuse make up less than 3 percent of all tax investigations, despite payroll taxes generating about a third of all federal tax revenue.

How do U.S. payroll taxes compare to other countries?

The United States’s labor tax policies remain competitive, if not the lowest among developed economies in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

The “tax wedge” reflects the total tax burden placed upon labor or the percentage of the cost of employing a worker attributable to taxes. This calculation includes personal income taxes and employer/employee payroll taxes.

For example, in the United States, the tax wedge for a single employee making the average wage is 30.5 percent. To see how we arrive at this number, we must first find the cost to employ a worker earning the average wage and the net take-home pay of a worker making that average wage.

To find the cost to employ a worker making the average wage, we add up the costs to the employer. This includes gross wages and the employer’s social security contributions (7.65 percent plus 0.6 percent on the first $7,000 in income for unemployment insurance).

Cost to Employ Average Worker, U.S.

Wage earnings | $64,889 |

Employer Social Security contributions | + $5,285 |

Average labor cost | = $70,174 |

Next, we find an employee’s net take-home pay. This is found by taking an employee’s wage earnings, subtracting income and payroll taxes, and adding cash transfers. This hypothetical single worker receives nothing in transfers, as they have no children and earn too much income to be eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit. State and local tax figures are averaged nationwide and vary significantly by state and locality.

Net Take-Home Pay for Average Single, Childless Worker, U.S.

Wage earnings | $64,889 |

Employee federal income taxes | - $7,044 |

Employee state and local income taxes | - $4,088 |

Employee Social Security contributions | - $4,964 |

Cash transfers | + $0 |

Net Take-Home Pay | = $48,793 |

Finally, the total tax wedge is calculated by subtracting net take-home pay from the average labor cost and dividing this resulting figure by the average labor cost.

($70,174 - $48,793) = 30.47 percent

$70,174

We arrive at a total tax wedge of 30.47 percent, meaning that about 30.5 percent of the cost to employ the average worker comes from the tax burden in the United States.

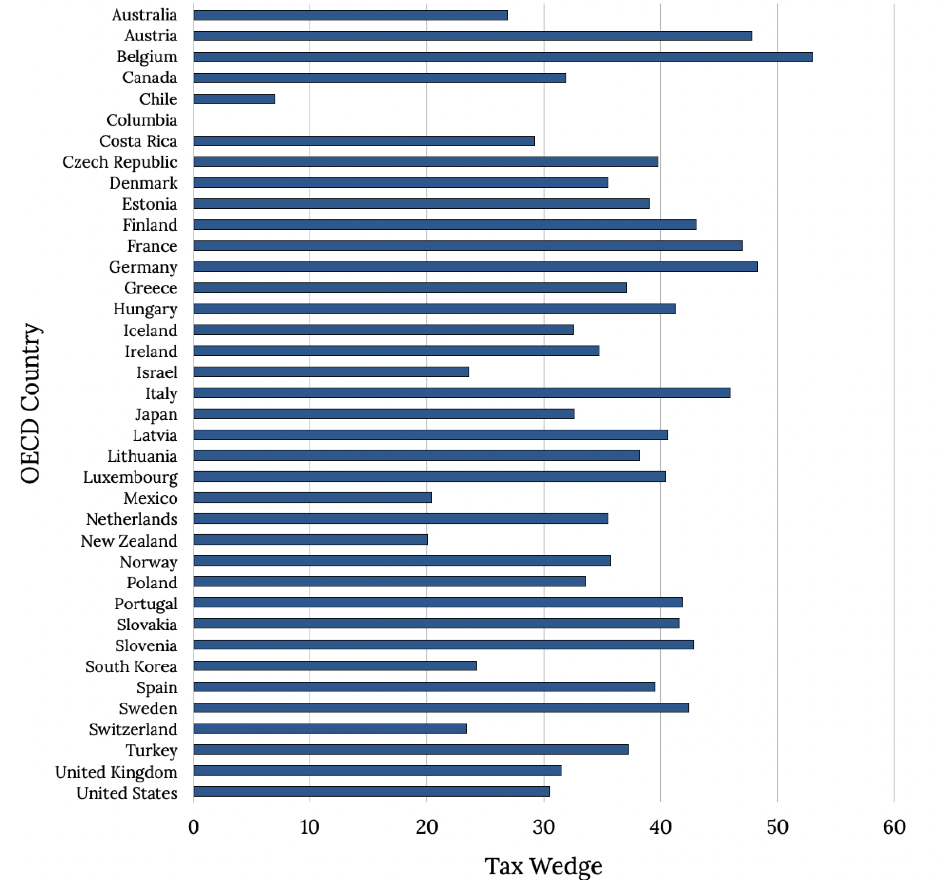

While this tax burden is not low, it is competitive in the broader OECD context. The following chart shows the tax wedge for the average worker in each OECD country.

Total Tax Wedge by Average Wage, OECD Countries

While the tax wedge in the United States is lower than OECD members in Oceania and South America, it does have the 29th-lowest tax wedge out of 38 OECD member countries. This allows the country to remain competitive as a destination for employers, an important policy to maintain and improve upon in the future.

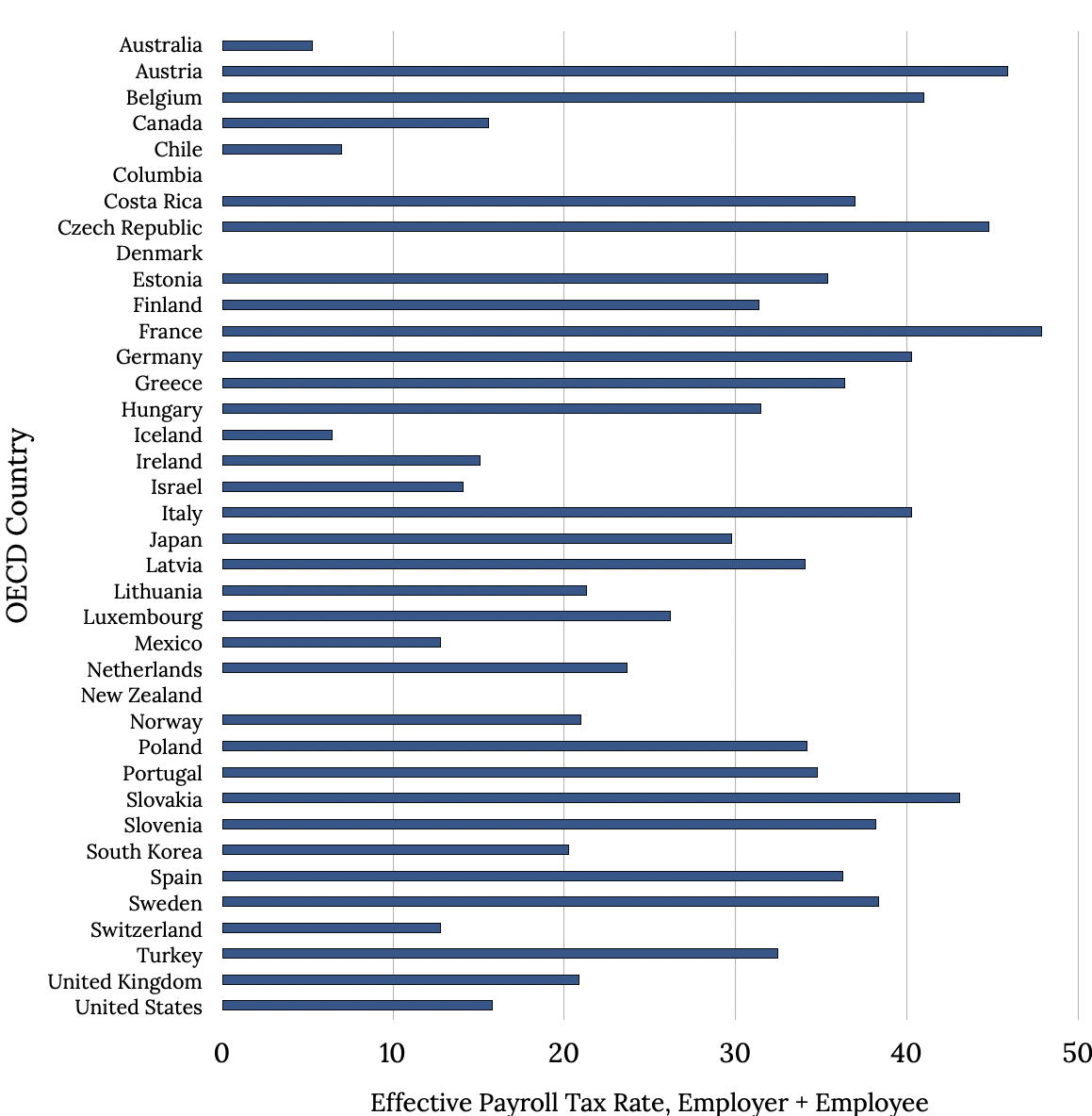

Looking specifically at payroll taxes, the United States is similarly well-situated compared to many other OECD countries, even if it does not offer the lowest payroll tax rates in the OECD. The following chart shows total payroll tax rates for employees earning the average wage in each OECD country.

Employer/Employee Payroll Taxes by Average Wage, OECD Countries

Once again, Oceania and South America boast meager payroll tax rates, while most of Europe has higher rates. Denmark’s zero percent payroll tax rate is somewhat misleading as it does not directly transfer revenue from a specific mandatory tax into its social security systems, funding them primarily through ordinary tax revenues.

But it’s important to remember that correlation is not always causation regarding labor tax rates and economic strength. Many already-wealthy European countries have pivoted to a model of more expansive social safety nets (and the taxes that fund them), while more recently developed countries remain more focused on growth and competitiveness.

Maintaining a competitive labor tax policy is crucial in allowing the United States to remain ahead of other competitive countries and prevent employers from seeking to relocate abroad.

Notably, the notion that taxing something gets you less of it remains valid for labor. Studies have consistently found that higher tax wedges result in higher unemployment rates and vice versa. That’s not a surprising conclusion — after all, as it becomes more expensive to employ workers, it would make sense that employers would be able to hire fewer of them.

The Toolkit

How should policymakers consider changing unemployment to ensure good use of payroll taxes?

In response to the heavy demand on payroll taxes across the country, policymakers must consider innovative reforms to address the societal need for a safety net for people to bounce back from unemployment.

However, demands from the COVID-19 pandemic have certainly highlighted places where state unemployment programs could benefit from changes. The government can be more responsive under challenging times and adaptable, so the stresses of this system don’t hold back businesses from investing in the workforce.

After much consideration and research, National Taxpayer Union Foundation recommends that state policymakers consider using our toolkit. This toolkit includes policies you can tailor to help any state’s programs and an example of where certain states could start applying these tools.

While all 50 of America’s state UI programs are different, below are key policy ideas lawmakers can consider to reduce fraud, improve efficiency, and decrease reliance on the high percentage of payroll taxes the government takes from employers and employees.

Specific reforms like employing work-search and drug-testing requirements and implementing a one-week waiting period are essential to re-enact after the pandemic, now that the enhanced benefits are no longer necessary. But this list takes a new look, after what we learned during those challenging times, and specifically targets improving the efficiency and effectiveness of unemployment in the future.

TOOL #1

PROBLEM: Benefits remain the same in good times and bad

SOLUTION: Adjust benefit levels to the state of the economy

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that benefits needed to increase and programs needed to adjust to meet the high demand from unemployment across the nation. However, it is also necessary for states to consider reducing the benefits and services when the economy is in full swing.

Therefore, states should consider implementing a sliding scale for benefits that reacts to the economic conditions at a given time. When jobs are plentiful, there should be a lower need for people to remain on unemployment instead of searching for a valuable, family-supporting job. However, states also need to put in safeguards for taxpayers to ensure that when the economy is slow and jobs aren’t available, unemployment insurance is available and is running efficiently to provide needed benefits accurately.

States should consider reducing the number of available benefit weeks and adjusting the number of available benefit weeks to the unemployment rate. Currently, 36 states offer 26 weeks of unemployment insurance, with seven (Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, and North Carolina) periodically updating their available unemployment benefits based on the unemployment rate. This adjustment is known as indexing, which increases the number of benefit weeks as the unemployment rate increases.

CASE STUDY: Florida

In June 2011, Florida Governor Rick Scott signed HB 7005 into law. This legislation reformed Florida’s unemployment compensation system. Specifically, HB 7005 cut back the maximum number of weeks a person could receive unemployment benefits from 26 to 23 weeks when the jobless rate is 10.5 percent or higher.

The maximum steps down by one week for each half-percentage point, the unemployment rate is below 10.5 percent, reaching 12 weeks of benefits once the rate is 5.0 percent or less. This commonsense reform illustrates a sliding scale reform that NTUF recommends states to consider. When jobs are available, it is illogical for people to collect unemployment benefits from taxpayers when they could be working in the economy.

The bill also revised the tax calculation formula for 2012 to provide minor savings to many employers across the state based on each individual company’s experience with the system. This measure mitigated the exponential tax increases forecasted for the following year. Businesses should be rewarded for good behavior, and the unemployment system should continue to be tweaked so they aren’t unnecessarily penalized.

CASE STUDY: North Carolina

In 2010, several states were battling the effects of the recession. Many state unemployment insurance systems struggled to keep their trust funds solvent. North Carolina was one of those states. By 2013, North Carolina had taken out $2.7 billion in federal loans for its unemployment trust fund, among the highest nationwide.

Unlike other states, North Carolina policymakers took action, ensuring they would avoid finding themselves in another fiscally vulnerable position again. They adopted reforms to the unemployment system that linked how long individuals could collect benefits to economic conditions. Under those changes, individuals are eligible for 12 weeks of unemployment benefits when the state’s unemployment rate is at or below 5.5 percent. As the unemployment rate rises by half a percentage point, claimants are eligible for an additional week of benefits — up to a maximum of 20 weeks.

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: Montana Montana is currently the only state in the nation that provides up to 28 weeks of unemployment insurance. Not only should Montana consider at least reducing benefits to a maximum of 26 weeks like other states, but officials there should consider taking the lead of other states who have greatly reduced the benefits they provide unemployed people during strong economic times. |

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: Wisconsin Before the pandemic, Wisconsin made significant strides in addressing the solvency of the unemployment trust fund in addition to reducing fraud. Under former Governor Scott Walker, Wisconsin’s trust fund reached a positive balance of $1.65 billion in 2018, representing a complete reversal from the fund's lowest point of a $1.68 billion shortfall in 2010. Under the governor’s leadership, fraud declined by 42 percent, while total benefit payments fell by 11 percent. The combination of reforms to improve the unemployment system in Wisconsin has been evident. It should continue to bolster unemployment trust funds, cut taxes for small businesses, and move the unemployed back to work by indexing unemployment insurance benefits to economic conditions. While Wisconsin has positioned itself well, there is always room for improvement. When the unemployment rate is high, it undoubtedly will take employees longer to locate work. When unemployment is low and available jobs are plentiful, there should be the expectation that individuals will find employment at a quicker rate. |

TOOL #2

PROBLEM: Work-search programs lack effectiveness

SOLUTION: Require a worker’s skills to be assessed at the time of application

Currently, in many states, there is a lag in time with work-search requirements that entirely relies upon an unemployed person to initiate this job-search process weeks into receiving benefits. That doesn’t need to wait; a skills assessment should start when applying for unemployment benefits.

States should consider requiring a new claimant to participate in an initial skills review when an application for benefits is submitted. Then, results could immediately be reported to the workforce system and coordinated with openings that employers in the state need. Especially when states face worker shortages, this could speed up matching potential skilled workers with employers looking to fill open spots.

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: Ohio and Pennsylvania Given the large number of unemployment insurance claimants in both Ohio and Pennsylvania, despite having relatively low unemployment rates, these states would benefit significantly from improving their work-search programs. Matching the application process with a skills assessment would immediately make the unemployment systems in these states more efficient, to help people find jobs that fit their skills and capabilities, ultimately end their reliance on the funds paid for via payroll taxes. |

TOOL #3

PROBLEM: Criminals scam benefits from the deceased, jailed

SOLUTION: Implement thorough eligibility checks

One of the most frequently identified cases of unemployment fraud in states nationwide is that benefits are simply paid out to people who never should have received benefits in the first place. While this happens for many reasons, the pandemic highlighted how crime rings used Social Security numbers of the deceased or those who were ineligible due to incarceration to receive benefits fraudulently.

To ensure that only those who qualify for unemployment benefits under state law get those benefits, states should bolster their efforts to ensure they accurately distribute payments. To do this, they should:

Cross-reference corrections records when applying for benefits and periodically throughout the term of eligibility;

Specify when an employee is disqualified from benefits related to committing a crime connected with work, regardless of imprisonment, and specify that a claimant in prison is disqualified from benefits;

Cross-match birth and death records; and

Codify agency rules related to excluding irrelevant evidence and revise the admissibility of hearsay evidence to be established as fact.

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: Mississippi Following the wake of heavily increased levels of unemployment benefits provided across the country in 2020 and 2021, states uncovered flawed payments or abuses of the unemployment insurance system. Mississippi was among those states to announce that an audit discovered problems with administering unemployment benefit payments, distributing more than $117 million in fraudulent claims. Among the recipients of improper payments were people who had never lost their jobs, inmates, and others who never qualified to receive aid. |

TOOL #4

PROBLEM: People living in another state are receiving benefits

SOLUTION: Flag claimants at application and verify

Fraud, however, doesn’t only occur with those incarcerated or criminals trying to scam the government out of money. There are several places where payments are improperly made to people who should have never received a benefit check.

This can happen when benefits are given from a state other than the state where the claimant resides or worked. Benefits could also be paid from multiple states within the same disbursement timeframe.

By ensuring that only eligible claimants receive benefits, states can help maintain economic stability. When benefits are targeted to those in need, it can help support consumer spending during economic downturns.

Furthermore, payments can sometimes be made in the name of a person other than the account holder. Similarly, there are ways to detect whether numerous deposits or electronic funds transfers indicate a claimant is receiving multiple payments from one or more states. States should also identify whether a claimant received more payments in the same timeframe than similarly situated customers receive.

To do this, states should consider the following policies:

Incentivize financial institutions to partner with unemployment insurance agencies in which withdrawing funds in a lump sum via cashier’s checks, prepaid debit cards, or transferring funds to out-of-state accounts is prohibited. While pre-loaded debit cards can be fiscally efficient for providing government benefits (e.g., nutrition assistance), if a given state’s UI program does not allow such tools, this could indicate an overpayment for a given recipient.

Entice financial institutions to flag accounts receiving unemployment funds where wire transfers to foreign accounts are occurring, or bank accounts have been recently opened.

Cross-reference email accounts that may appear in more than one application for benefits in addition to bank accounts receiving more than one benefits deposit.

Strengthen financial information requirements and request additional banking information from potential claimants.

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: Iowa The state of Iowa paid approximately $30 million in fraudulent unemployment insurance claims during the pandemic. The state saw applicants lying about their qualifications for benefits and occasionally struggled to verify banking information with an individual's identity in addition to distributing unemployment insurance benefits via prepaid debit card. Iowa, which has improved its system leaps and bounds in recent years, would strengthen its ability to ensure benefits are paid to eligible claimants by instituting additional checks and balances as mentioned in the toolkit. |

TOOL #5

PROBLEM: Workers who hadn’t paid in receive benefits

SOLUTION: Require payments for independent contractors

Historically, independent contractors were not covered by state unemployment insurance laws, unlike employees. Previously, suppose a worker had been "performing services for pay" for an employing unit. In that case, there is a presumption in the law that the worker is an "employee," not an independent contractor.

However, the eligibility for independent contractors to access benefits was expanded in many states following the pandemic despite not previously paying into unemployment.

A simple but standard reform to the unemployment insurance system should allow independent contractors the option to contribute into the system. This addition would encourage entrepreneurship since many independent contractors choose their work arrangement because it gives them flexibility and the opportunity to pursue entrepreneurial ventures. Access to unemployment insurance can provide a safety net for these individuals while they're between projects or businesses.

However, if independent contractors choose not to contribute, they would be ineligible to collect benefits. As with other insurance benefits, this should make sense. If people don’t pay their premiums, they’d be ineligible for the payments when they experience a downturn. Allowing workers who don’t pay into the system to receive benefits doesn’t make sense and isn’t fair to those employers and employees who have been taxed for years.

To avoid further avenues of fraud, states should require independent contractors to pay in before and provide additional verifying information when applying for unemployment. For example, independent contractors should be required to provide tax form 1040-SE for the prior year and a Schedule 1 and Schedule C form before any claim approval.

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: Florida, Georgia, and Vermont Given the high percentage of independent contractors in Florida, Georgia, and Vermont, which rank near the top in the nation for self-employed workers, this is a simple but significant change to unemployment that should be considered. Independent contractors' income can be highly variable due to the nature of their work. Adding the ability to buy into unemployment insurance could help smooth out income fluctuations by providing supplemental income during lean periods. Furthermore, without access to unemployment insurance, independent contractors who face economic downturns might rely more heavily on public assistance programs, potentially increasing the burden on social services and government resources. |

TOOL #6

PROBLEM: Current structure of unemployment is inefficient

SOLUTION: Treat unemployment like traditional insurance

Following the issues brought to light by the pandemic, it would be wise for policymakers to consider the conventional insurance format for dealing with unemployment.

Risk pooling has long been a successful method for people interested in protecting themselves against life-changing crises. We enter into insurance contracts to mitigate the risk of car accidents, fire, poor health, etc. States could undoubtedly consider a private option for potential instances of unemployment.

Individuals have the ability to ensure their mortgage payments will be made if they become unemployed. If the government got out of the unemployment insurance business, private alternatives would swiftly emerge, giving workers more flexibility than the current system.

While this concept could be considered bold, it's worth considering given the many problems many state unemployment insurance funds face.

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: Illinois, California, Connecticut & New York State unemployment trust fund accounts are within the federal unemployment trust fund, where states deposit their payroll taxes for unemployment benefits. Illinois, California, Connecticut, and New York have the nation's least solvent unemployment insurance funds and could benefit from examining a private option to increase efficiency and solvency for the future of their state’s unemployment programs. Private companies in these states could bring innovative approaches to managing and funding the unemployment compensation system, potentially leading to more sustainable models. Furthermore, private entities would be incentivized to operate more efficiently than the government, reducing administrative costs and improving the fund's overall financial performance. |

TOOL #7

PROBLEM: Claimants lack incentives to find a new job

SOLUTION: One-time bonuses for locating employment

In September 2021, eleven states — Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Virginia — offered return-to-work bonuses instead of the enhanced unemployment benefits to encourage residents to accept jobs as businesses struggled to find workers. In essence, those states decided they would use federal money to encourage people to locate employment rather than paying people not to work.

While many states have implemented different work-search requirements to collect benefits, many claimants consider submitting an application or communications with a hiring manager as meeting agency job search requirements. So, instead of leaving unemployment, they continue collecting benefits without proper incentives to locate employment.

States must consider new ways to motivate those unemployed to find jobs and not rely on taxpayer funds. Even those states that have resisted implementing work-search requirements need ideas to incentivize workers. Furthermore, sometimes taking a job may come at a cost to a claimant where they would receive less while working than when they receive unemployment benefits. This happened frequently during the pandemic when the federal government created enhanced benefits.

To help smooth the transition into fulfilling work and earning independently, states should consider enacting pilot programs to study the effectiveness of one-time bonuses for when people find new employment. These bonuses should be geared toward incentivizing those who obtain a job and retain that job for some time, encouraging long-term independence instead of reliance on the government.

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: West Virginia West Virginia is a prime example of a state where lawmakers should consider one-time bonuses for finding long-term work. It has the country’s lowest labor force participation rate, seasonally adjusted at 54.6 percent in June 2023, far below the national participation rate of 62.6 percent. Beginning a pilot program like this would help get those who are on unemployment insurance working in the economy. The approximately 7,300 people claiming unemployment weekly in West Virginia as of August 2023 would then be able to reduce their reliance on payroll tax-funded unemployment insurance while helping the state’s labor force needs |

TOOL #8

PROBLEM: Benefits are paid to those fired due to misconduct

SOLUTION: Ensure those provided benefits are deserving

Due to unfortunate and unforeseen vagueness in regulations of the unemployment insurance program, employees who have been legitimately fired with cause have been able to continue to receive unemployment benefits. This leaves payroll taxpayers on the hook for providing the funds for these checks and affects employer ratings and their tax rate unfavorably when they have to continue paying taxes for employees rightfully terminated.

Administrative rules and statute changes are necessary to fix how employee misconduct is determined and defined by altering statutory review standards and specifying specific forms of documented misconduct, such as theft from the employer, chronic absenteeism, or lack of punctuality.

APPLYING THE TOOLKIT: Virginia In 2022, the national average of improper payments was 21.52 percent, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. However, Virginia’s rate was more than double that at 43.8 percent — nearly half of that came from separation issues. In these cases, eligibility problems stemmed from claimants receiving benefits that they shouldn’t have, arising from why they left previous employment. In Virginia, employees legitimately fired with cause are still receiving unemployment benefits. Here, state lawmakers and rulemakers should work with employers to tighten laws and rules in their state to ensure that after administrative hearings, lenient judges and bureaucrats cannot award benefits to people who showed misconduct at their previous jobs. |

I read this whole payroll tax report. Now what?

Thanks for making your way through this lengthy report. Hopefully, this paper helped you better understand how federal and state governments use payroll taxes — beyond seeing standard federal and state income and FICA taxes withheld from your every paycheck. But this is just the beginning.

For far too many, the payroll tax is considered the “cost of doing business.” It’s a policy that not enough people scrutinize or question despite being one of the largest revenue sources for the federal government and one of the most expensive costs for employers and employees. Plus, it’s easy to understand why so many states are ready to cut income taxes instead of tackling the issue of payroll taxes in their state — it’s far less complicated and messy. Even experts in this field are learning new things about how these levies are assessed and spent.

However, as this report showed the many hoops businesses go through to collect and withhold payroll taxes and the actual cost that citizens pay, we hope state policymakers will continue learning and closely examining how they can be better guardians of these taxpayer dollars.

Please take these broad ideas of reform — from indexing benefits based on the unemployment rate to verifying wages and income to prevent improper payments — and then use any opportunity to research how they might help your state and implement them. The NTUF team stands ready to assist you as you work to stand up for payroll taxpayers and improve the entitlement programs these taxes fund.

About the Authors

Leah Vukmir is the senior vice president of state affairs for National Taxpayers Union Foundation. She is the former assistant majority leader of the Wisconsin State Senate. You can email Leah at lvukmir@ntu.org.

Jess Ward is the senior director of state affairs for National Taxpayers Union Foundation. She is a small business owner, veteran, prior law enforcement officer, and formerly worked in the Wisconsin State Senate as a chief of staff. You can email Jess at jward@ntu.org.

Mattias Gugel is the director of state external affairs for National Taxpayers Union Foundation. He is a former communications and policy director in the Wisconsin State Senate. You can email Mattias at mgugel@ntu.org.

Andrew Wilford is the director of the Interstate Commerce Initiative and a senior policy analyst at National Taxpayers Union Foundation. He is also a columnist at RealClearMarkets and the Daily Caller. You can email Andrew at awilford@ntu.org.