The nonpartisan Government Accountability Office (GAO) publishes an annual report, called the Weapons Systems Annual Assessment, that details the performance of the Department of Defense (DoD) on their costliest weapon programs, as well as progress on their implementation of best practices for avoiding cost overruns and schedule delays. Below, we comb through the report and find some of the most mismanaged weapons acquisitions projects. We also offer some suggestions for DoD and Congress in the months and years ahead. We also highlighted GAO’s reporting on the high effectiveness of their best-practices recommendations at increasing efficiency -- and DoD’s neglect in implementing those best practices.

Our key recommendation for Congress is to use the annual National Defense Authorization Act to limit DoD’s ability to spend taxpayer dollars on identifiably mismanaged acquisition programs. In turn, our recommendations to DoD include a more thorough implementation of GAO’s best practices and a more explicit pathway for ending mismanaged acquisitions programs before they spiral out of control.

DoD Acquisition Projects Experiencing Major Problems

F-35 Lightning II

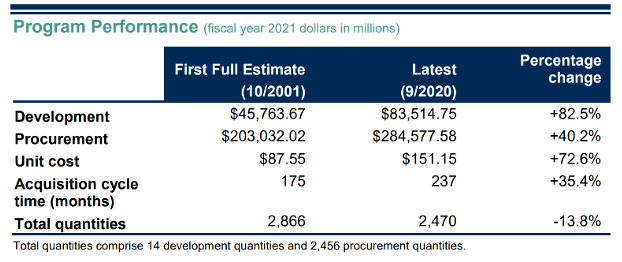

The “infamous” F-35 has been NTU’s target for years. Here’s a look at GAO’s comparison of the original 2001 estimates for the program to the status today:

The cost overruns are in part the result of technical flaw after technical flaw.

DoD did report some rare good news about the F-35 program: compared to last year’s assessment, the total cost of the acquisition has decreased by $28.6 billion. GAO writes that this is “primarily due to a reduction in negotiated unit costs, including reduced labor rates.” This makes the good news a bit murky: Yes, the program is slightly less expensive than we thought it would be last year; however, this is not because DoD made the difficult decisions it needs to make regarding the F-35. It is mostly because of a decrease in wages for the workers building the planes.

The F-35 keeps getting delayed because of design flaws. Every time a new flaw is identified, the whole project gets behind schedule. It has gotten so behind schedule that the planes that were built early on need significant updates, an effort DoD calls “Block 4” modernization. GAO writes, “Total Block 4 development costs — included in the Program Performance table — grew from $12.1 billion last year to $14.4 billion this year … The program continues to deliver Block 4 capabilities late because of its overly optimistic schedule. As of October 2020, the contractor had delivered only eight of 20 capabilities planned to-date.” DoD’s rush to Initial Capability and a long list of design deficiencies mean that the cost of retrofitting already-built F-35s continues to be a major liability for the program.

GAO also identified several risks for further cost overruns or delivery delays:

“As of November 2020, 11 open category 1 deficiencies remain that could jeopardize safety or security, and 861 open category 2 deficiencies remain that could impede mission success. The program office plans to resolve seven category 1 deficiencies prior to the completion of operational testing. The remaining four category 1 deficiencies will remain open until the program completes software improvements currently scheduled for delivery in 2021. This will not occur until after the full-rate production decision, which could lead to additional retrofit costs to existing aircraft.”

Additionally, GAO noted that the program still has not caught up to industry best practices:

“The program reported that it has yet to achieve statistical control of critical production processes, in contrast to leading practices. Improvement in reliability and maintainability continues to be slow, with some metrics not meeting program goals”.[1]

Littoral Combat Ship (LCS)

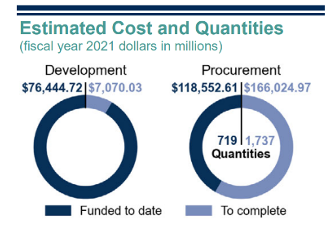

A perennial portrait of DoD overindulgence, the LCS continues to experience problems. Even as the Navy shrunk the number of ships it intended to procure by nearly 25 percent (64 to 49), the total procurement cost increased by 3 percent, meaning the procurement cost per unit rose by 34 percent.

In 2019 the Navy began the process of acquiring 20 Constellation Class Frigates (FFG 62s), which it describes as “intended to develop and deliver a small surface combatant based on a proven ship design that provides enhanced lethality and survivability as compared to the Littoral Combat Ship”.[2] The value the LCS provides to the US Navy’s Force Structure seems to diminish, even as the cost of the project grows steadily.

It is worth noting that for the LCS, just like for the F-35, not a single one of GAO’s best-practice recommendations were met in the timeframe GAO recommends. In fact, the F-35 still has yet to demonstrate a Manufacturing Readiness Level of at least 9, which GAO recommends be met before full-scale production is funded (Production on the F-35 began in 2007). More on GAO’s best practices below.

DDG 1000 Zumwalt Class Destroyer

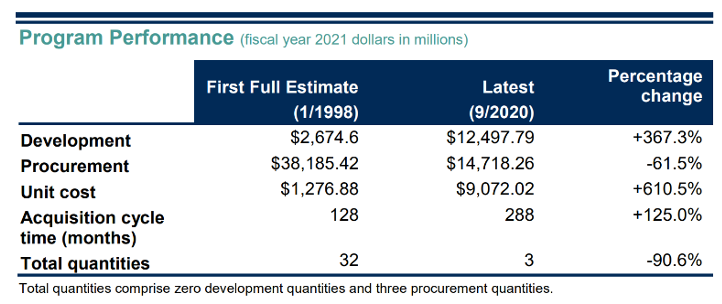

It only takes a brief glance at the Program Performance chart to understand that something went majorly wrong with this system’s acquisition. Development costs have quadrupled, the cost per unit is seven times the original estimate, and the acquisition schedule is twice as long as first anticipated.

For all that trouble, the Navy is walking away with three ships, which won’t be finished until 2024. The above chart doesn’t even tell the full story when it comes to overruns: “The DDG 1000 program continues to have several immature technologies as it approaches the planned conclusion of operational testing in 2021 ... Maturing these technologies throughout the construction and testing process will likely lead to additional cost and schedule delays.”

GAO also wrote that:

“The Navy now plans to complete software development for the class in fiscal year 2022—a 24-month delay since our 2020 assessment, largely due to overly optimistic development schedules … Without the originally planned level of capability and automation, the Navy has had to permanently grow the crew size by 31 sailors, increasing life-cycle costs.”[3]

This project only gets more expensive, even as it shrinks from its original capability targets.

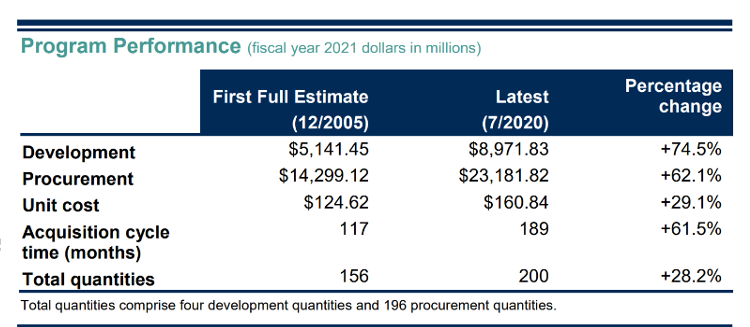

CH-53K Heavy Replacement Helicopter

The CH-53K is designed to carry heavy items (like personnel, equipment, and armored vehicles) to inland destinations not otherwise reachable. The program began in 2003 and has yet to meet Initial Capability. Despite a 30-percent increase in the cost per unit compared to the first full estimate, the Navy has upped its order from 156 to 200 units. See the Program Performance chart:

At the beginning of development, the CH-53K met very few of the best practices GAO recommends to keep technical flaws to a minimum.

In its analysis of the helicopter’s technical readiness, GAO writes:

“Since 2017—when the program entered production—the program office identified 126 different technical issues during developmental testing … the deficiencies discovered to date and ongoing developmental testing efforts may cause the program to undertake additional design changes.”

The CH-53K is a case study in why best practices exist: to avoid technical problems that eat up time and taxpayer dollars to fix.

GAO also found that “the prime contractor and the program office lack up-to-date information about production processes,” which presents risks of quality and capacity issues.[4] For example, the Navy program office has delayed an assessment of the contractor’s production line until November 2022, despite the contractor’s relocation to a new facility in 2018. It is particularly concerning that the office would overlook simple leading practices regarding communication with the contractor, because foregoing these practices opens the door to even more technical issues on a project that has been dogged with delays and overruns.

KC-46 Tanker Modernization Program

The Air Force uses aerial refueling tankers to refuel larger planes while they are still in the air. The refueling fleet is dominated by KC-135s, but the Air Force is replacing this fleet with KC-46s. However, this process keeps getting delayed by massive schedule adjustments. When the system started development in February 2011, it was supposed to be completed before the end of 2017. As of today, operational tests are not scheduled to be completed until 2024.

Schedule delays keep occurring because the KC-46 keeps running into technical problems during testing. These include: fuel manifold leaks, auxiliary power unit drain mast cracks, auxiliary power unit duct clamps detaching, two other deficiencies which relate to shortcomings with the remote vision system cameras and their display, and another deficiency related to the boom being too stiff during refueling attempts. Like many of the systems on this list, technical issues translate directly into delays and overruns.

The Air Force has been successful in holding Boeing financially responsible for most of these issues. The KC-46 has thus far avoided significant cost overruns compared to the original estimates from 2011, but the reports notes that, “Until testing is complete, Boeing may find additional deficiencies that could require further design changes, adding risk of cost growth and schedule delays”. GAO seems to indicate that the repeated delivery delays could have been largely avoided had best practices been followed in this system’s development process.[5]

“Knowledge-Based Practices”

GAO put together a list of best practices for DoD to obtain information before making production decisions. It terms these “knowledge-based practices”, and they serve as checkpoints for DoD to make informed decisions before they make major purchases. Here are some examples:

- Before investing in product development:

- Complete preliminary design review before system development starts

- Demonstrate technologies to a high readiness level—Technology Readiness Level 7—to ensure technologies fit, form, and function within a realistic environment

- Conduct independent cost estimates and program assessments

- Before funding prototype construction:

- Release 90 percent of engineering design drawing packages

- Demonstrate a system-level integrated prototype design that meets requirements

- Before initiating full-scale production:

- Demonstrate manufacturing processes on a pilot production line

- Demonstrate that critical processes are capable and in statistical control

- Build and test production-representative prototypes to demonstrate product in intended environment[6]

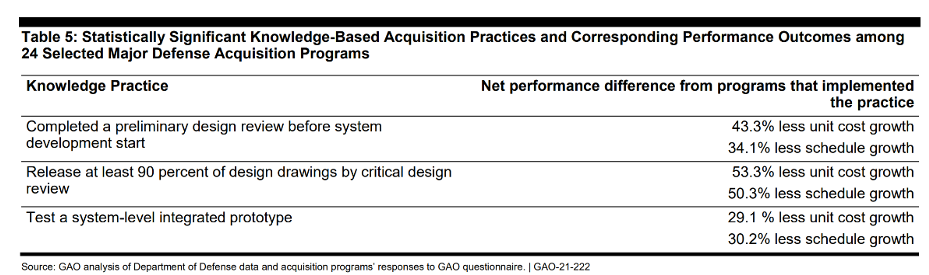

GAO found that Major Defense Acquisition Programs (MDAPs) that implement applicable “knowledge-based practices” tend to experience between 30 percent and 50 percent less cost growth and schedule delays. From the report:

Note: GAO was only able to provide this information regarding these three practices because these were the only three with enough data. The number of programs that implemented the remaining practices was insufficient to allow for statistically significant results.[7]

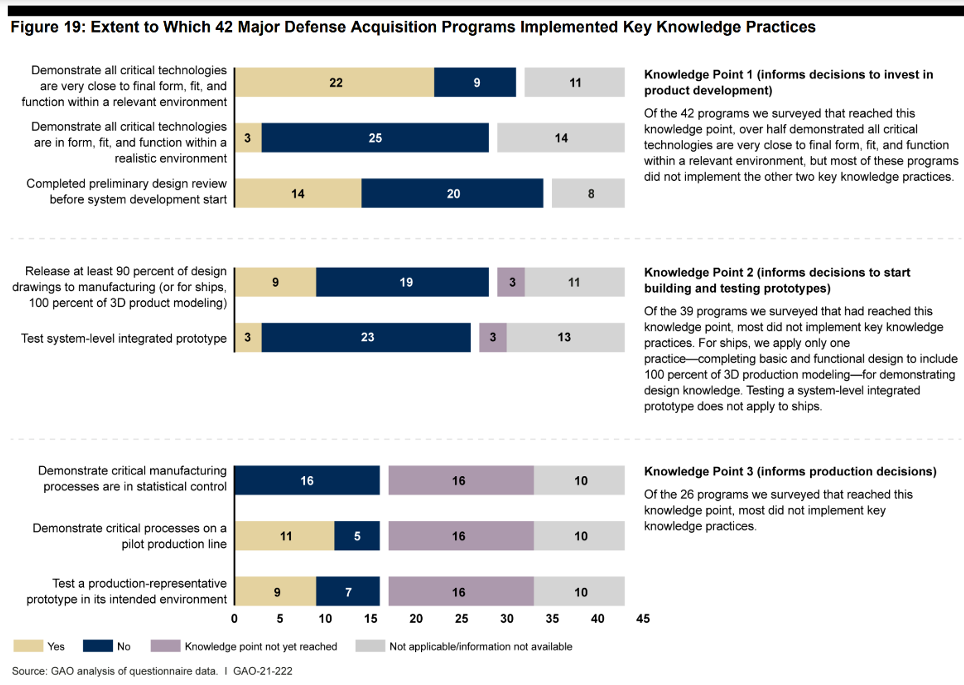

So far, the idea seems simple enough: follow best practices and make informed decisions and there will be fewer problems down the road. However, a disturbingly low number of MDAPs actually follow these best practices. Here is a chart from GAO:

GAO “found that over half of MDAPs we surveyed proceeded with acquisition decisions without obtaining [relevant] knowledge.” A similar trend was found for Middle-Tier Acquisition (MTA) programs. [8]

GAO included the same knowledge-based practices recommendation in last year’s annual report. Yet, there was no improvement from DoD on implementing these standards. GAO also noted: “Future MDAPs we surveyed, in contrast, reported that they plan to attain recommended knowledge by development start. It will be important that they follow through on these plans to ensure the cost and schedule benefits of these practices.”[9]

Conclusions

DoD makes financial decisions on our behalf. We expect them to be good stewards of our tax dollars, and when they do not meet that charge, it is our responsibility as Americans to hold them accountable. The Government Accountability Office puts out a lot of information to help us do that, but ultimately, the duty falls on the American people. Here are some things DoD could and should be doing to spend more smartly.

DoD should be following the knowledge-based practices the GAO has identified. These are simple checkpoints to help ensure decision-makers have all of the relevant information before making massive purchases. It would not be unreasonable for the DoD to issue a department-wide requirement that MDAP and MTA programs follow these best practices.[10]

DoD needs a better system for identifying when to “call it quits” on large acquisitions. For example, the DDG 1000 Zumwalt Class Destroyer program started in 1998 and the total cost per ship has increased sevenfold since then. The whole program will cost over $25 billion dollars, and the Navy will walk away with only three ships (compared to the original estimate of 32). Had difficult decisions regarding this ship been made years ago, tens of billions of dollars could have been saved or put to much better use. DoD stands to benefit from an explicit methodology for determining when to simply walk away from an acquisition project.

Congress is tasked with overseeing the executive branch, a task it has increasingly neglected. A great place for Congress to exercise this authority again is more stringent oversight of the defense budget. Given DoD’s repeatedly demonstrated inability to avoid boondoggles like the ones cited above, it would not be out of step for Congress to assert itself more here. Congress could easily use the annual defense authorization bill to place caps on appropriations for given acquisitions programs, or end fruitless programs altogether.

[1] Quote and charts regarding the F-35 obtained from pp. 201-202. Government Accountability Office, “Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” 2021. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-222.pdf

[2] “Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” pp. 175-176.

[3] Quotes and chart regarding the Zumwalt Class Destroyer obtained from “Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” pp. 169-170.

[4] Quotes and chart regarding the CH-53K obtained from “Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” pp. 165-166.

[5] Quote and information regarding the KC-46 obtained from “Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” pp. 89-90.

[6] Examples taken from Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” pp. 223-224. For a complete list of GAO’s knowledge-based practices, please click here.

[7] Quote and table obtained from “Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” p. 36.

[8] Quote and chart obtained from “Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” p. 34.

[9] “Weapons Systems Annual Assessment,” p. 33.

[10] GAO has been making recommendations on best practices for weapons acquisition since 2004. This report goes into even further detail on GAO recommendations and DoD’s implementation status. In short, while DoD has made mild progress in reforming weapons acquisition, they still fall far short of GAO’s guidance.