Introduction

Yesterday, Judge Amit Mehta of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia issued the long-anticipated remedies judgment in United States v. Google. The decision rejected most of the remedies sought by the Department of Justice, most notably divestiture of the Chrome browser, but imposed new limits on exclusive contracts and introduced a requirement to share certain data with qualified competitors. While many have characterized the ruling as a legal victory for Google, it leaves open important questions about its implications for consumer privacy and competition in a market increasingly shaped by generative AI.

The ruling follows the court’s August 2024 decision, in which Judge Mehta found that Google had unlawfully maintained monopoly power in two relevant markets—general search services and search text advertising—principally through exclusionary agreements with distributors. The September 2025 judgment prescribes remedies intended to address this conduct, seeking to balance the government’s call for structural measures with Google’s arguments about consumer benefits and an evolving search landscape increasingly shaped by generative AI chatbots.

The DOJ’s Proposed Remedies

More specifically, the DOJ’s proposed remedies in November 2024 included:

- Divestiture: Forcing Google to sell the Chrome browser, and, if necessary, the Android operating system.

- Exclusionary agreements ban: Prohibiting Google from signing exclusive agreements with distributors for Google Search placement.

- Mandatory selection screens: Requiring all browsers to display a selection screen unless users explicitly consent to Google as the default.

- Pre-installation ban: Banning Google from pre-installing search access points on its devices.

- Third-party payments ban: Banning payments for pre-installation of Google search on non-Google devices

- Self-preferencing ban. Preventing Google from favouring its own search results in applications such as Android, Maps, YouTube, and Gemini.

- Data-sharing mandate: Requiring Google to make its search index and related data available to all third parties at reasonable cost.

- Transparency obligations: Imposing additional disclosure requirements on advertisement-related data.

Many of the remedies proposed by the Department of Justice were disproportionate to the infringement identified in the court’s August 2024 ruling. For instance, divestiture of the Chrome browser would have significantly disrupted Google’s integrated ecosystem and diminished the user experience without directly addressing the exclusionary agreements found to be unlawful.

Obligations to share the entire search index and related data could also have created serious privacy, data security, and even national security risks—particularly given that anonymization does not always prevent the recovery of sensitive search histories. More broadly, such measures risked imposing disproportionate restrictions at a time when the search market was already being reshaped by competition from generative AI chatbots.

Key Provisions of the Remedies Judgement

By contrast, Judge Mehta’s September 2025 judgment adopted a narrower set of remedies. The court barred Google from entering or maintaining exclusive distribution agreements for Google Search, Chrome, Google Assistant, and Gemini. It also required Google to make portions of its search index and aggregated user-interaction data available to qualified competitors, rather than to any third party. At the same time, the court declined to order the DOJ’s structural remedies, such as divestiture, rejected mandatory choice screens, and limited the scope of Google’s data-sharing obligations.

More specifically, here are the key takeaways from Judge Mehta’s ruling:

- Structural remedies rejected: The court declined to order divestiture of Chrome or the Android operating system, finding such measures disproportionate and not directly tied to the exclusionary agreements identified in the liability ruling.

- Third-party payments permitted: Google may continue paying distributors such as Apple or Samsung to set Google as the default search engine. The court reasoned that banning such payments would risk harming distribution partners—particularly smaller firms—and consumers who benefit from Google’s services.

- Exclusive contracts prohibited: Google is barred from entering or maintaining exclusive agreements for installing Google Search, Chrome, Google Assistant, and Gemini on non-Google platforms.

- Limited data-sharing obligations: Rather than requiring Google to share all search index and related data with any rival, the court imposed a narrower obligation. Google must provide certain aggregated search index and user-interaction data to “qualified competitors,” with privacy safeguards in place.

- Syndication requirements: Google must continue offering search results and text-ad syndication services to rivals, largely on terms already available commercially.

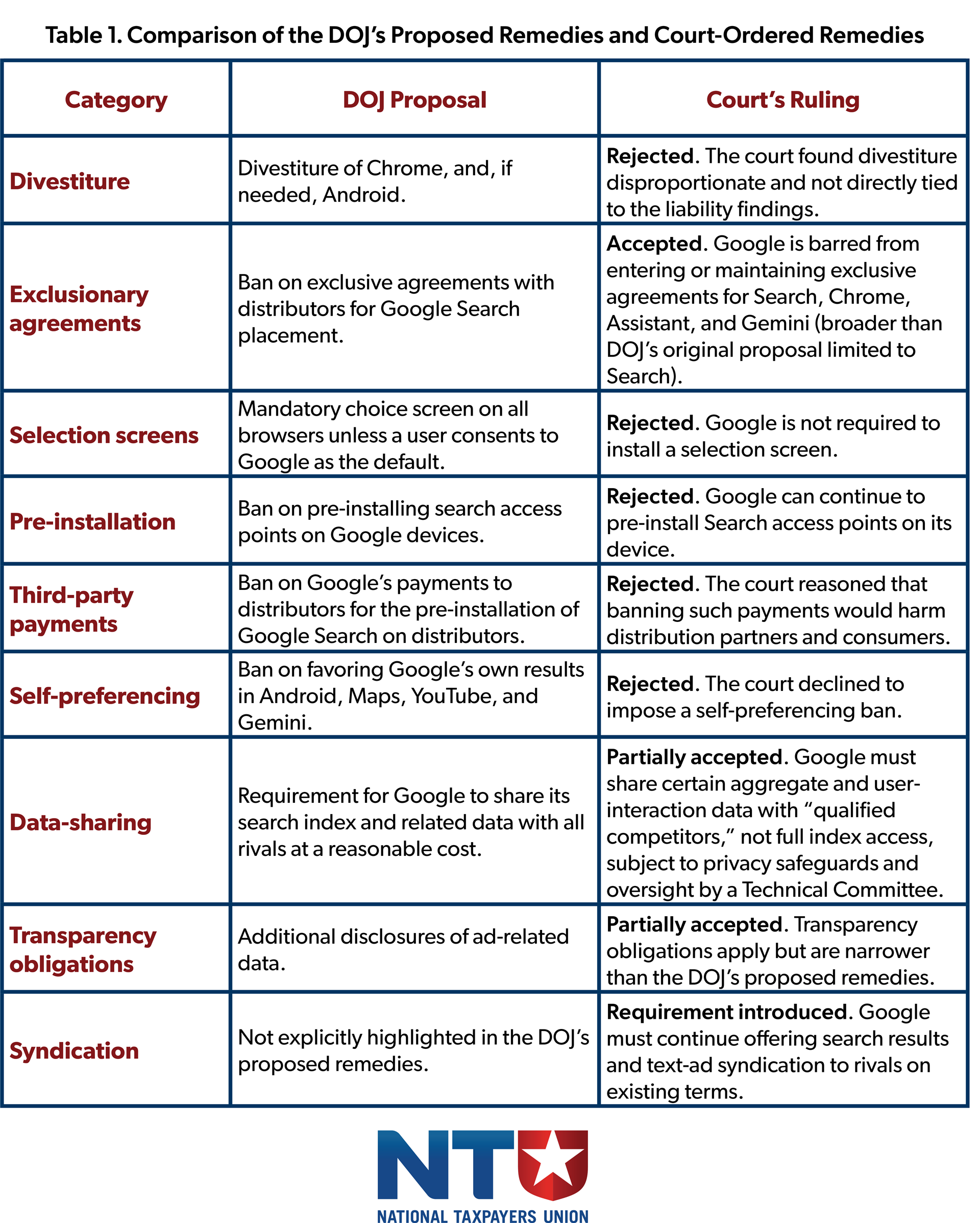

Taken together, these measures represent a significantly narrower set of remedies than those sought by the DOJ—perceived by many as a legal victory for Google. Most of the government’s proposals were rejected, with the court tailoring its order to the exclusionary conduct identified in August 2024 (Table 1). The judgment acknowledged the growing competitive pressures that search engines already face from generative AI chatbots and credited Google’s pro-competitive justifications, noting that several of the DOJ’s proposals could have harmed both distribution partners and consumers. Overall, the court aimed to balance competition concerns with the risks of over-correction, reflecting caution in distinguishing unlawful conduct from what it described as “growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.”

Data Privacy and Security Concerns

Nevertheless, significant concerns remain, particularly in relation to data privacy and security. The judgment imposes two data-sharing obligations: Google must provide a one-time snapshot of its search index to qualified competitors, and it must also disclose certain “user-interaction” data—covering queries, clicks, and dwell times—on an ongoing basis. Of the two, it is the continuing disclosure of user-interaction data that carries the greater privacy risks, as behavioral datasets typically contain more sensitive information than an index of webpages, are harder to anonymize effectively, and must be shared on a recurrent basis—thereby heightening the risk of re-identification and security breaches over time.

The court itself acknowledged these risks and therefore conditioned disclosure on privacy-enhancing techniques, including k-anonymization, noise injection, and generalization. Data sharing will be subject to oversight by the Technical Committee, established to resolve complex and technically nuanced disputes about how the arrangement is implemented in practice. In addition, the judgment carves out advertising and advertiser-level data, which are typically regarded as especially sensitive.

These modifications mitigate but do not eliminate the residual risk that sensitive search activity could be inferred from ostensibly anonymized datasets—particularly in the event of operational errors or procedural shortcomings. If poorly implemented, the data-sharing requirement could create new privacy and security vulnerabilities at a time when U.S. residents lack the baseline protections already in place in the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Canada.

Consumer Welfare and Competition Considerations

Beyond privacy, questions remain as to whether the remedies will materially enhance consumer welfare or improve competition. Switching costs in search are already close to zero, as users can change their default engine at no cost and with minimal effort. Although Judge Mehta prohibited Google from entering exclusive default agreements, the likely impact on consumer choice is limited. Evidence from the European Union—where the European Commission went further by requiring choice screens on Android devices—indicates that such measures have little effect on behavior, with 97% of users still selecting Google. Against this backdrop, exclusivity prohibition may deliver only marginal competitive benefits, while doing little to improve consumer welfare.

Conclusion

Overall, the District Court’s judgment enabled the government to claim credit for imposing new limits on Google, while at the same time sparing the company from the most far-reaching measures. Markets quickly interpreted the outcome as a win for Google, with its share price rising by nearly 8% after the decision.

By rejecting structural divestitures in favor of more targeted obligations, the court has sought to address competition concerns without unduly disrupting Google’s broader ecosystem. Nevertheless, the ruling raises significant privacy issues that will need to be managed carefully as data-sharing arrangements with qualified competitors take shape. These concerns are likely to feature prominently as Google challenges both the remedies judgment and the underlying liability decision on appeal.