(pdf)

Congress has appropriated trillions of dollars in the past few months to economic and public health measures meant to combat the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic. Though the U.S. may be far from defeating the virus, there will come a time in the near future when policymakers will have to grapple with the enormous additions they have just made to the federal debt.

As federal lawmakers look to offset recent and future COVID-19 spending, one of the first places they should explore is the Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) account. The OCO account, which has allowed the Departments of Defense (DoD) and State to spend above the decade-long discretionary spending caps enacted under the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 (and even subsequent increases to BCA caps), has increasingly become a source for “base” DoD spending and for “enduring” costs expected to last beyond the Global War on Terror.

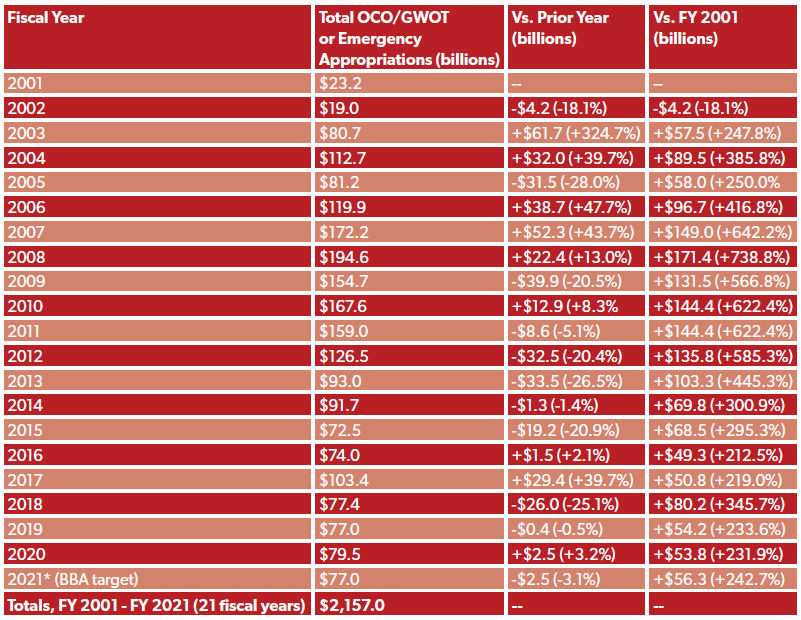

From September 11, 2001 through the end of fiscal year (FY) 2019, Congress appropriated over $2 trillion “in support of the broad U.S. government response to the 9/11 attacks and for other related international affairs activities.” Lawmakers made these appropriations through either the OCO/Global War on Terror (GWOT) designations or the looser emergency spending designation that preceded OCO/GWOT from 2001 through 2008.

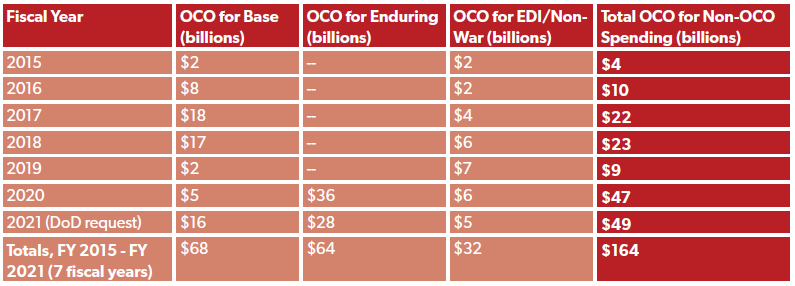

However, in recent years an increasing share of OCO/GWOT appropriations are actually dedicated to either “base” requirements that would normally be included in DoD’s regular budget request or “enduring” requirements that are expected to outlast the immediate contingency operations OCO was designed to fund. (Throughout this paper, "base" spending refers to DoD's annual discretionary budget.)

Executive and legislative branch policymakers share blame here. DoD sought to adhere to statutory budget caps for defense spending in its FY 2020 budget request last year, but reached a wildly unsustainable spending target of $750 billion by pouring $165 billion into its OCO request. Of this $165 billion request, 59 percent ($98 billion) was for base requirements, 21 percent ($35 billion) was for enduring requirements, and an additional four percent ($6 billion) was for the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) - not considered a part of the Global War on Terror. Only 16 percent of the OCO request ($26 billion) was for mission-related costs in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria.

Congress, for its part, has made it easier for DoD to use OCO for base and enduring requirements by passing budget deals that authorize OCO amounts well above and beyond what are needed for contingency operations. Ahead of the FY 2017 budget debate, the Obama administration was supposed to release a plan for transitioning enduring costs in the OCO budget to the base budget. DoD officials declined to submit the plan, though, “since the fiscal year 2017 budget was developed so as to be consistent with the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, which increased the amount of enduring costs funded in OCO.”

Lawmakers in both parties and stakeholders across the ideological spectrum are interested in reforming OCO and reducing appropriations dedicated to the OCO account. Progressives like Reps. Barbara Lee (D-CA) and Ilhan Omar (D-MN) have proposed decreasing or eliminating OCO funding, while conservatives like Sens. Mike Enzi (R-WY) and Rand Paul (R-KY) have proposed drawing down OCO budget authority over several fiscal years. Recent National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs), which almost always pass with bipartisan support, have included requirements for DoD to report on enduring costs funded through OCO and have sought to clarify the roles of inspectors general (IGs) in overseeing OCO funds.

Reformers have a long way to go, though. The upcoming FY 2021 NDAA will likely include $69 billion for OCO, which is the statutory cap for security-related OCO funds passed by Congress in the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2019. Unfortunately, that figure is much too high. It is not too late, though, for Congress to include more reporting requirements for DoD and its OCO spending in FY 2021 and beyond. In a post-BCA world, lawmakers also need to look at how to properly cap OCO funds starting in FY 2022.

The Scope of the Problem: A Look at the Last Two Decades of OCO

Based on existing research compiled by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) through FY 2019, FY 2020 appropriations bills passed by Congress, and the FY 2021 BBA target for OCO funding, it is estimated that by September 30, 2021 Congress will have appropriated more than $2.1 trillion to the OCO/GWOT or emergency designations for the Global War on Terror.

More troubling though, is that in the last six fiscal years Congress has appropriated OCO funds for three categories of spending that fall outside the more limited definition of contingency operations that many feel Congress and DoD should be following for its OCO spending: 1) base requirements; 2) enduring requirements; 3) the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI) and other “non-war” costs. Below is a breakdown of that spending, along with DoD’s FY 2021 request for these three categories.

In total, that is $164 billion that should have been made to compete with other priorities in DoD’s base budget (not to mention the rest of the federal budget), which, unlike the OCO account, was subject to BCA discretionary spending caps from FYs 2012-2021. Instead, Congressional appropriators have managed to stuff an additional $164 billion in taxpayer funds to DoD that should have been subject to spending caps. The table above indicates the problem is getting worse, not better, with time.

As mentioned earlier, stakeholders may have to wait for the situation to improve. Because the BBA of 2019 established a $77-billion target for OCO in FY 2021, DoD and the State Department can be expected to request up to the maximum amount for FY 2021. Congress can largely be expected to give the agencies what they are asking for. (Note the problem above with DoD’s scrapped plan to phase out OCO spending from FYs 2017-2020.)

That does not mean Congress cannot act now, though, to rein in OCO for FY 2022 and beyond. Below is a menu of policy recommendations, some small and some very large, to reform OCO. Most are mutually exclusive, meaning they can be enacted in tandem, but some involve making a choice between one policy and another. At NTU we are fairly agnostic as to the direction policymakers take, as some involve tradeoffs for military officials beyond the scope of NTU’s expertise. We note that it is paramount, though, for Congress to put a stop to the practice of stuffing unrelated base and enduring funds into the OCO account when they belong in the regular DoD or State Department budget. Just as every federal agency, state government, business, and household has to tighten their belts in an extraordinarily challenging economic environment, DoD needs to do the same. OCO is a great place to start.

Ten OCO Reform Options

Below are 10 policy recommendations for lawmakers to reform and, eventually, replace OCO. Six policy recommendations are ‘low-hanging fruit’ for the immediate future, and we believe they can be included and implemented in the FY 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). Lawmakers in the House and Senate are currently working on the FY 2021 NDAA, with initial drafts from Armed Services Committee leaders due out later this spring.

The other four options are likely not realistic inclusions in the FY 2021 NDAA, but should be considered for FY 2022 and beyond. They are more extensive and disruptive reforms to OCO, and would spark intense debate among policymakers across the ideological spectrum - debate that could, in this challenging legislative environment, distract from the prospect of more achievable gains over the nearer term. Nonetheless, we believe all would be an improvement over the OCO status quo.

Low-Hanging Fruit: OCO Reforms for the FY 2021 NDAA

Re-establish the Wartime Contracting Commission: Reps. Stephen Lynch (D-MA) and Jody Hice (R-GA) have already introduced legislation to implement this reform, the Wartime Contracting Commission Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 3576). The Commission, initially created by the FY 2008 NDAA, closed its doors in September 2011. During its three years of existence, the Commission uncovered between $31 billion and $60 billion of taxpayer dollars lost to waste, fraud, and abuse through wartime contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan. The lessons and recommendations of the Commission were valuable for lawmakers and DoD officials. H.R. 3576 would reestablish the Commission with a mandate to study federal agency contracting funded by OCO. The Commission could uncover wasteful practices with current OCO funds, and encourage Congress and/or DoD to make changes that save taxpayer dollars.

Ensure that OMB and DoD finish work on revised criteria for DoD’s OCO budget requests: In 2017, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) recommended that DoD and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) “reevaluate and revise the criteria for determining what can be included in DOD’s OCO budget requests.” DoD agreed with the GAO recommendation, but OMB and DoD have still not developed updated criteria. DoD is operating under 2010 criteria in 2020, even though GAO’s 2017 report points out that 2010 criteria did not account for much of 2017 OCO spending (like anti-ISIL operations in Iraq and Syria and various counterterrorism initiatives). Congress could step in, and formally direct DoD and OMB to develop updated criteria by a target date. Congress could also require DoD and OMB to update their OCO criteria with certain frequency - for example, once every two or three years - until the OCO fund no longer exists.

Require DoD to give Congress and OMB a plan for transitioning all existing enduring costs funded through OCO to the base budget: DoD pledged in FY 2016 to create a plan for transitioning all enduring costs funded through OCO to the base budget over four years (FYs 2017 - 2020), but never submitted the plan because lawmakers included overly generous OCO targets in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015. Now may be time for Congress to ensure DoD submits a plan for transitioning base and enduring costs funded by OCO to the base budget over some period of time, perhaps no longer than four years. This would help lawmakers if they decide to institute more aggressive caps on OCO funding in future years (see the second option under “Turning the Corner” below).

Require DoD budgets to break out enduring costs funded through OCO: We credit our friends at the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) for this reform option. As long as the OCO fund continues to include enduring or base costs, DoD should be required to break these costs out in their annual budget request. Although DoD did this in their FY 2020 and FY 2021 budget requests, Congress could codify this practice into law, and/or require more detail on exactly which base and enduring requirements OCO funds will meet in a given fiscal year.

Require five-year projections of all OCO costs: We also credit our friends at POGO for this option. Congress could compel DoD to project what OCO costs will look like over the next five fiscal years - for base, enduring, and contingency operations. This would help lawmakers determine how fast to draw down OCO budget authority or when the fund could be completely eliminated. It is difficult, of course, to project what contingency operations costs will look like in five years. Acknowledging the challenge of projecting contingency costs, Congress could allow DoD to give confidence levels of its five-year spending estimates. But requiring DoD to make some effort on this front is better than offering absolutely zero certainty to lawmakers on how much cap-busting spending DoD will ask them to approve going forward.

Prohibit OCO/GWOT spending on base activities in the State and Foreign Operations appropriations bill: Though OCO funding in the State and Foreign Operations appropriations bill has taken up only 10 to 20 percent of total OCO appropriations over the last five or six fiscal years, it represented a significant portion of the nation’s international affairs budget at one time. According to the nonpartisan CRS, “OCO as a share of the international affairs budget grew from about 21% in FY2012 to a peak of nearly 36% in FY2017.” OCO then leveled off to 15 percent of the international affairs budget in FY 2019. However, some lawmakers appear intent on using OCO funds for base international affairs activities, a problem that mirrors DoD behavior outlined above. Congress could prohibit OCO funds from being spent on base activities for international affairs agencies like the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and save several billion dollars in the process.

Turning the Corner on OCO: Long-Term Reforms

The work on OCO reform does not stop with this year’s NDAA debate. Beyond FY 2021, lawmakers need to think about phasing the OCO fund down for good. They should even consider an alternative mechanism for funding the military’s contingency operations, one more in line with historical precedents for emergency spending. Below are four major reform options. The first two can be combined with any of the other options, but lawmakers would have to choose between options three and four (establishing an OCO reserve vs. funding contingency operations through supplemental appropriations and/or “emergency” designations). We consider each in turn below.

Enforce the existing definition of “contingency operation”: According to 10 U.S.C. § 101(a)(13), a “contingency operation” is a military operation that “is designated by the Secretary of Defense as an operation in which members of the armed forces are or may become involved in military actions, operations, or hostilities against an enemy of the United States or against an opposing military force,” or “results in the call or order to, or retention on, active duty of members of the uniformed services under section 688, 12301(a), 12302, 12304, 12304a, 12305, or 12406 of this title, chapter 15 of this title, or any other provision of law during a war or during a national emergency declared by the President or Congress.” Congress could limit OCO appropriations to needs that meet this definition of a “contingency operation.” This would theoretically limit the amount of OCO funding directed to base or enduring requirements, but remains broad enough that either appropriators or agency officials could game the system to continue spending large amounts of money through the OCO account. Further clarification could come from harmonizing this definition of a “contingency operation” with the new OMB/DoD criteria on what constitutes a permissible OCO request (see above).

Institute more aggressive caps on OCO funding, with a declining cap year to year until OCO is nominal or zero: S.Con.Res. 12, the Senate GOP budget resolution from Senate Budget Committee Chairman Mike Enzi (R-WY), provided a total of $130 billion in OCO budget authority for fiscal years (FYs) 2020 and 2021, and $0 in FYs 2022, 2023, and 2024. S.Con.Res. 11, the budget resolution from Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), provided $82.7 billion in OCO budget authority for FY 2020 and $0 for fiscal years 2021 through 2029. H.Con.Res. 128 from the 115th Congress (2017-2018), by former House Budget Committee Chairman Steve Womack (R-AR), would have drawn down OCO from $77 billion in budget authority to $0 in budget authority from FY 2019 through FY 2026, and would have kept OCO authority at $0 in FYs 2027 and 2028. All three of these options present potential models for drawing down OCO budget authority in future budget resolutions, and Congress could also draw conclusions from DoD’s five-year projections of OCO needs (see above) and its breakdown of base and enduring costs funded through OCO versus actual contingency needs funded through OCO.

Require DoD to establish an OCO reserve, funded through Congressional appropriations year to year, for use on actual contingency operations: Much like many American families set aside a reserve fund for emergencies, Congress should consider establishing a rainy day fund for the U.S. military so that it can draw on that fund for contingency operations and emergencies. There are bipartisan proposals to establish rainy-day funds for the entire federal budget: the House Democratic Blue Dog Coalition has proposed “creating a federal rainy-day fund—something that almost all states have,” and Senate Republicans have recently proposed requiring Congress to budget for federal disaster spending in the future, since “disaster aid funding has become an annual exercise.” Five-year projections of OCO costs will be critical for such reserve planning, as will establishing DoD’s plan for transitioning enduring costs currently funded through OCO to the base budget.

Remove the OCO/GWOT designation, forcing Congress to instead fund operations through supplemental appropriations and/or “emergency” designations: The OCO designation did not exist until FY 2011. Congress didn’t even fund Global War on Terror expenses through regular appropriations until FY 2004. Before that, and historically, Congress has relied on supplemental appropriations to fund war activities. Congress could consider phasing out OCO and ensuring that enduring requirements for America’s military engagements overseas (such as the ongoing Global War on Terror) are funded through the regular DoD budget. When unexpected military engagements arise that require additional funding, DoD could approach Congress for those supplemental appropriations and Congress could weigh that request (and any spending offsets to such supplemental appropriations). As mentioned above, Congress could start by removing the OCO designation for State and Foreign Operations agencies, before moving to the larger task of phasing out and removing the OCO designation for DoD.

Conclusion: Reforming OCO is A Better Deal for Taxpayers, Watchdogs, and the Military

The above reform options range from minor to significant, but each of them would improve transparency and accountability in OCO spending. This will benefit taxpayers, who have forked over tens of billions of dollars to OCO for needs that should be met in the capped discretionary defense budget. It will benefit watchdogs, who can better keep track of waste, fraud, and abuse through the base budget. Lastly, we believe OCO reform will benefit the military, by forcing Pentagon leaders to answer tough questions about priorities for a 21st-century military and to disclose more about current and future costs for contingency operations around the globe.