(pdf)

Executive Summary

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) began as drug claims adjudicators more than 50 years ago, but today are vertically integrated with major health insurance companies and play a major role in prescription drug pricing and access in America’s health care system.

PBM practices and profits have a direct effect on U.S. taxpayers, given federal and state government agencies directly contract with PBMs in some cases (Medicaid, state employee health benefits programs) and contract with plans who own or use a PBM in other cases (Medicare Part D, the Federal Employees Health Benefits or FEHB program). Taxpayers also directly (via Affordable Care Act premium tax credits) and indirectly (via the employer-sponsored insurance exclusion) subsidize privately-obtained health coverage, either by an individual or through their employer.

PBM expansion, consolidation, and integration in the past few decades has rested on a promise to save health insurance plans, health insurance enrollees, and taxpayers significant amounts of money through rebate negotiations with manufacturers, strategic drug formulary placement, and utilization management.

Unfortunately, NTU’s review of government data indicates that several PBM business practices siphon funds away from consumers and taxpayers, through practices such as spread pricing, the use of exclusive specialty pharmacies, and the exercise of significant leverage over plans, manufacturers, and taxpayers. Both state government officials and business leaders have decried a lack of transparency in the PBM business model, which makes it more difficult for plans and employers to make informed, cost-conscious decisions about the pharmacy benefits they provide enrollees and workers.

While most PBM reform efforts in recent years have happened at the state level, members of both parties in Congress have expressed interest in studying PBM business practices and considering legislative reforms that protect taxpayers and consumers. With a Republican-controlled U.S. House and Democratic-controlled U.S. Senate in 2023, PBM reform may be one of the few health policy initiatives that can be enacted into law in the near future.

Our paper, “How Pharmacy Benefit Managers Impact Taxpayers and Government Spending,” provides a comprehensive overview for readers on the history of the PBM industry and how PBM business practices past and present affect American taxpayers. We reach the conclusion that targeted reforms will allow private businesses involved in the health sector to secure a higher return-on-investment for their customers and federal and state government officials to win a better deal for taxpayers.

Our recommended reforms include:

Enhanced transparency on PBM spread pricing;

Additional reporting from PBMs on the use of specialty pharmacies;

Efforts to strengthen public-private negotiations over PBM contracts;

Hearings and consultations with PBM industry disruptors;

Exploring the reverse auction model for PBM contracts that has successfully worked to reduce costs for several states; and

Requiring PBMs to address potential conflicts of interest in their Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees.

Other, more aggressive paths proposed by some progressive lawmakers – especially encouraging the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to penalize or ‘break up’ larger PBMs – will do more harm to the market (and taxpayers) than good.

Introduction

To their proponents, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are “key drivers in lowering prescription drug costs and increasing access.” To their opponents, PBMs are oligopolist middlemen who “[put] their profits before your medicine.” Who’s correct?

As is the case with many fierce policy battles happening in Washington, D.C. and state capitals around the country, the most plausible answer can be found somewhere in between the two ideological camps.

PBMs began playing a role in the health care sector more than 50 years ago, primarily “adjudicat[ing] prescription drug claims,” but they play a much larger role in prescription drug access, utilization management, and payment today than they did in the 20th century.[1] Today, three PBMs control roughly 80 percent of the market, and all three are vertically integrated with a major health insurer (CVS Caremark with Aetna, Express Scripts with Cigna, and OptumRx with UnitedHealthcare).

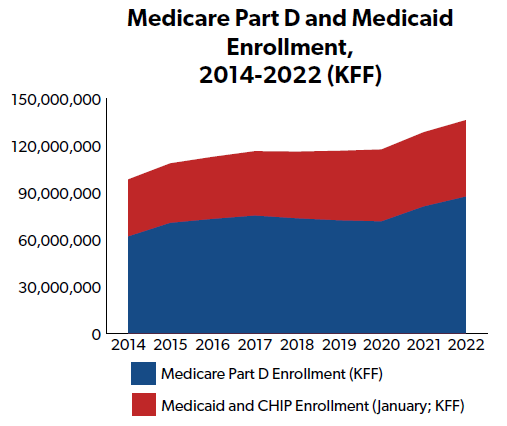

Those three PBMs, and their smaller competitors, manage prescription drug benefits and payments for tens of millions of Americans with privately- and publicly-sponsored health insurance, including tens of millions in Medicare Part D (Medicare’s prescription drug benefit) and Medicaid. Their practices also have a direct impact on health care costs and premiums in the private marketplace, which U.S. taxpayers subsidize. In other words, taxpayers have a lot at stake when it comes to the costs PBMs impose on the health care system and the benefits they bring to the same system.

This is just one reason NTU has weighed in on PBM practices and policies in the past. In February 2017, we noted the benefits PBMs can offer the health care sector, namely “lower[ing] drug costs for beneficiaries” by “acquiring price concessions from both brand-name and generic drug manufacturers, [obtaining] rebates, and [building] networks of more affordable pharmacies.”[2] In November 2017, we wrote to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that “[c]ertain value-based strategies, such as those employed through pharmacy benefit managers, can be of service in controlling the growth of taxpayer-funded health programs.”

NTU has also expressed concern with the impacts of some PBM practices on consumers and taxpayers. In March 2021 we argued, of legislation that was pending in the Wisconsin state legislature at the time, that the state’s “[p]harmacy benefit reform will allow health plan payers to know amounts paid to pharmacies, which in turn allows the health plan to know the percentage paid to Pharmacy Benefit Managers.”

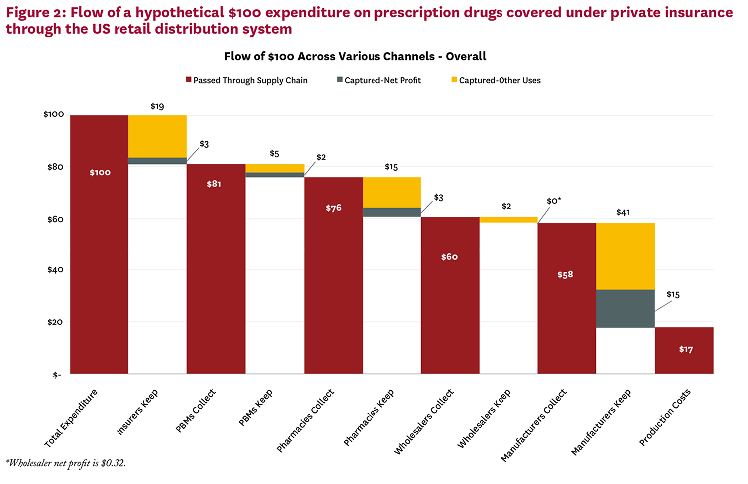

PBMs matter to taxpayers because their business practices and revenue streams directly affect how much money the government spends and saves on prescription drugs. PBMs derive their resources from several other stakeholders in the pharmaceutical supply chain – manufacturers, insurers, and pharmacies, through retained rebates, fees, spread pricing, and more – all of which affects taxpayers and consumers. These revenue streams must be weighed against the purported benefits PBMs offer consumers and taxpayers – namely, lower costs on prescription drugs, and prescription drug benefit and utilization management – and against a number of counterfactuals (e.g., what if PBMs did not exist, what if the government set prescription drug prices instead, etc.).

NTU’s research, described in further detail below, indicates that government distortions create perverse incentives and significant inefficiencies throughout the pharmaceutical supply chain, including the parts of the supply chain affecting (and affected by) PBMs. Specifically, prescription drug price controls in Medicaid and the 340B Program, along with insurance regulations added by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), have likely induced both higher list prices from pharmaceutical manufacturers and the creation of ‘closed’ (more restrictive) formularies by PBMs – both trends that have been heavily criticized by Members of Congress and federal regulators across the ideological spectrum.

The negative impacts of existing government price controls should inform federal policy on PBMs going forward. NTU believes the following PBM reforms are taxpayer-friendly and should be considered and debated by Congress:

- Enhanced transparency on PBM spread pricing for stakeholders operating in the federal health programs (namely, plan sponsors in Part D and Medicaid managed care, state governments running Medicaid programs, and pharmacists serving beneficiaries in both programs);

- Additional reporting from PBMs on the use of specialty pharmacies in Medicare and Medicaid, addressing a current gap in CMS reporting requirements;

- Efforts to strengthen public-private negotiations over PBM contracts, so that plan sponsors and state governments are getting the most ‘bang for the buck’ with PBM services;

- Hearings and consultations with PBM industry disruptors, to determine if any legislative or regulatory barriers stand in the way of additional competition in the PBM industry;

- Exploring the reverse auction model for PBM contracts that has successfully worked to reduce costs for several states, to see if such a model is applicable within Medicare or for private entities; and

- Implementing a long-standing, unimplemented CMS recommendation that PBMs address potential conflicts of interest in their Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees.

NTU has also found some PBM reform proposals that overreach at the federal level at this time. Those less promising proposals include:

- Requiring all PBM rebates nationwide to be delivered at the point-of-sale, whose impact on federal finances is still not thoroughly established;

- Banning spread pricing nationwide;

- Encouraging the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to pursue aggressive government investigations against PBMs or ‘breaking up’ the larger PBMs; and

- Encouraging the federal government to step in on private-sector negotiations between PBMs and pharmaceutical manufacturers with government price-setting.

NTU reviews all of the above proposals further in the paper. First, we review what PBMs do and how they make money in today’s health care system. Then, we summarize how government distortions in Medicaid, 340B, and the private insurance marketplace have encouraged some of the business practices policymakers and consumers object to today. Finally, we review the six taxpayer-friendly PBM reform policies that might work at the federal level, and the six policies that won’t work at the federal level.

The paper also includes four appendices of potential value to readers – one reviews pharmaceutical spending and the pharmaceutical supply chain in context. The second provides a more detailed history of the PBM industry from the 1960s to present. The third offers four case studies demonstrating how industry disruptors and/or public-private partnerships may provide more impactful and effective PBM reform going forward than anything contemplated by Congress, federal regulators, or the courts. The fourth provides an overview of recent state-based PBM reforms.

What PBMs Do and How They Make Money

A Brief History of PBMs

What follows is a brief history of PBMs and their role in the health care sector, from the 1960s to present. Readers interested in a more detailed history should review Appendix B.

PBMs began forming as health insurers began offering prescription drug benefits in the 1960s, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC).

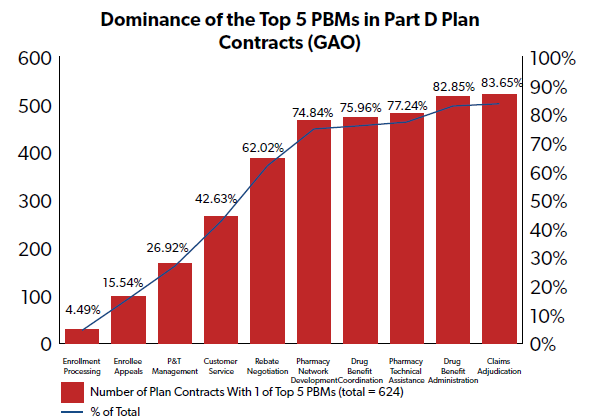

Consolidation in the PBM industry occurred around the early 1990s, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). By 1995, according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), five PBMs controlled 80 percent of the market. By the 2010s, three PBMs controlled a significant majority of the market: CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx. They remain the most prominent market players today, and provide pharmacy benefits for over 200 million Americans.

In the waning years of the Obama administration and during the Trump administration, policymakers in the legislative and executive branches began taking a greater interest in the role PBMs play in the pharmaceutical sector.

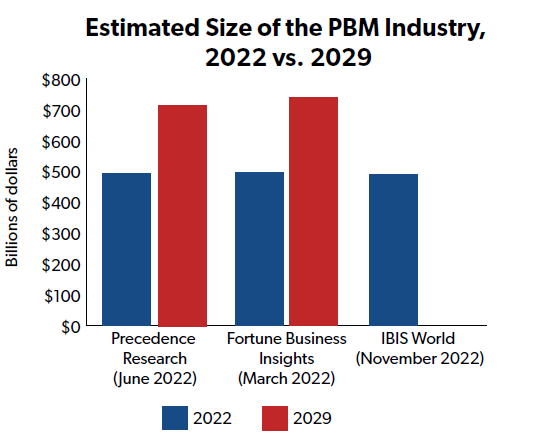

Despite these ongoing reform efforts, the PBM industry remains large and influential in the U.S. health sector. According to three separate industry analyses, the global PBM market was valued at between $467 billion and $495 billion in 2022, and could grow to around $750 billion by 2030.

PBMs and Taxpayers

Today, PBMs also play a major role in the federal health programs, including Medicare Part D, which serves 49 million people, and Medicaid, which serves 82 million people.[3]

Unlike some PBM contracts with private plan sponsors that rely on retained rebates and spread pricing (as reviewed in a 2021 Senate Finance Committee report and by other experts), it appears the primary source of revenue for PBMs in Medicare Part D is fees based on a) volume of prescription drug claims, b) number of members, or c) some combination of the two.

Use of PBMs in Medicaid, on the other hand, varies from state to state, but CBO has reported that: “[m]any states use pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to help administer drug benefits, develop preferred drug lists, and negotiate supplemental rebates with drug manufacturers.” Spread pricing is a more common practice in state Medicaid programs, and some states have investigated PBMs for aggressive spread pricing (especially on generic medications).

PBMs also have an indirect effect on federal taxpayers in how they manage private-sector prescription drug benefits. This is because PBM business practices have a direct impact on health insurance premiums in the private individual and employer-sponsored health coverage marketplaces. Federal taxpayers have a stake in private health insurance premiums in two ways: 1) the cost of employer-sponsored health insurance is generally not includible for federal income or payroll tax purposes, which is foregone revenue for the federal government; and 2) the cost of premiums in the ACA’s individual marketplace is subsidized by taxpayer-funded premium tax credits, or PTCs, which often requires federal spending on individuals and families whose PTCs exceed their federal income tax obligations.

Therefore, the money PBMs save plans, governments, and consumers – and the money they take, directly or indirectly, from those three stakeholders – significantly affects how much taxpayers pay for their and others’ health coverage.

PBM Revenue Streams

PBMs earn revenue from a variety of payers; each revenue stream has consequences for consumers and taxpayers:

- PBMs may retain a portion of the rebates they negotiate with manufacturers on prescription drugs (while passing the bulk of rebates on to plan sponsors and/or clients);

- They may retain a portion of the inflationary rebates they negotiate with manufacturers (which require manufacturers to pay PBMs when they raise the price of their drugs beyond specified rates within a specified time period);

- They may assess administrative fees on plan sponsors and/or clients;

- They may assess fees on pharmacies they work with, both in and out of network, and sometimes retroactively after adjudication of claims;

- They may earn money from ‘spread pricing’ practices; i.e. charging a plan sponsor more for a drug than a PBM reimburses a pharmacy for that same drug while retaining the difference; and

- Payments from manufacturers “for services that the manufacturer would otherwise perform, or contract for, and that represented the fair market value of those services.”[4]

Two of the more controversial revenue streams for PBMs, discussed in further detail below, are retained rebates and spread pricing. Federal and state lawmakers have introduced legislation that would limit or prohibit these practices by PBMs.

Evidence indicates that retained rebates and spread pricing are common revenue streams in PBMs’ private coverage and Medicaid lines of business, but are less common in Medicare Part D according to GAO.

In the private marketplace, on the other hand, administrative fees are often based on the list price of prescription drugs. This could incentivize manufacturers to set higher list prices and for PBMs to accept those higher list prices, according to the Senate Finance Committee:

“PBMs earn administrative fees from manufacturers each time a drug is dispensed at the pharmacy. Administrative fees vary by contract, ranging up to 5% of the WAC [wholesale acquisition cost] price for the insulin therapeutic class. These fees are a significant revenue stream for PBMs and likely act as a countervailing force against lower list prices—PBMs may be reluctant to push for lower WAC prices since it would reduce their administrative fee-based revenue.”[5]

For more on list prices, net prices paid, and pharmaceutical spending in context, readers should turn to Appendix A, “Pharmaceutical Spending in Context.”

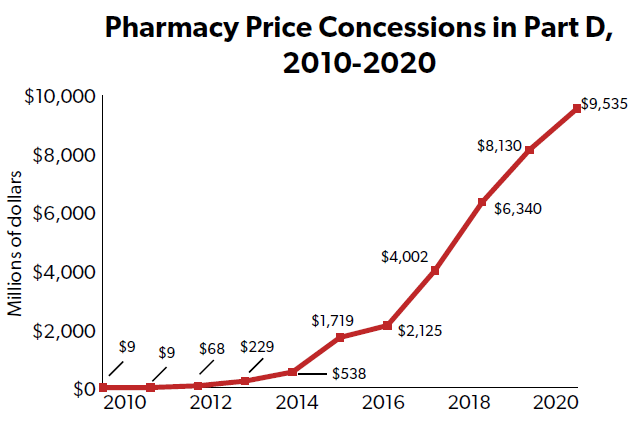

An additional, growing, and controversial source of PBM revenue, particularly in the Part D program, has been retroactive price concessions paid by pharmacies to PBMs after the sale of a drug to a customer. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in the text of a final regulation published in May 2022:

“In 2020, pharmacy price concessions accounted for about 4.8 percent of total Part D gross drug costs ($9.5 billion), up from 0.01 percent ($8.9 million) in 2010.

…Performance-based pharmacy price concessions, net of all pharmacy incentive payments, increased, on average, nearly 170 percent per year between 2012 and 2020 and now comprise the second largest category of DIR received by sponsors and PBMs, behind only manufacturer rebates.”

The American Pharmacist Association has raised numerous concerns with this PBM practice, claiming that fees can be “assessed weeks, or even months” after the sale of a drug.

“These price concessions negotiated between PBMs and pharmacies participating in Medicare Part D networks are assessed weeks, or even months, after Part D beneficiaries’ prescriptions are filled. Retroactive DIR fees resulted in pharmacies realizing only long after the prescription was filled that they did not recoup their costs. These retroactive fees also resulted in patients paying more at the pharmacy counter for their prescription drugs.”

However, CMS is already cutting down on this growing revenue stream, at least in PBMs’ Part D line of business. Starting in January 2024, PBMs will need to pass “all possible pharmacy price concessions” on to customers at the point of sale, which will have the effect of eliminating most if not all retroactive fees PBMs assess on pharmacies in Part D. It remains to be seen what effect, if any, these regulatory changes at CMS will affect the use and prevalence of retroactive pharmacy fees assessed by PBM in Medicaid and in their private lines of business.

How PBMs Decrease Costs for Consumers and Taxpayers

The primary way PBMs decrease costs for consumers and taxpayers is by negotiating rebates with manufacturers that reduce the costs plan sponsors and plan beneficiaries pay for prescription drugs. PBMs can negotiate larger rebates from manufacturers by either offering preferred formulary placement (especially over competitors with the same or similar drug products) or, conversely, by threatening to remove a manufacturer’s product from their formulary or to move the drug to a less preferred tier. Or, as a group of authors put it in a May 2021 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper: “the primary service PBMs offer payers is to run formularies on their behalf … [and] rebates function as bids in a contest for a favorable formulary position.”

When prescription drugs are on preferred tiers of a plan’s drug formulary, consumers may owe less money out of pocket for the preferred drug product than for drugs on lower tiers or drugs entirely off a plan’s formulary. Rebates earned by PBMs are often passed on to plan sponsors, who can then reduce premiums (or slow premium growth from year to year) by spreading those savings out among their entire customer base.

Since taxpayers directly subsidize premiums and drug costs in Medicare Part D, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act – and since they indirectly are involved in the employer marketplace through the tax exclusion on employer-sponsored insurance – rebates earned by PBMs that reduce premiums and out-of-pocket costs can reduce taxpayer costs as well.

The inflationary rebates PBMs negotiate with manufacturers may also limit the rate at which drug costs increase within a plan, reducing upward pressure on premiums (and, consequently, on taxpayer-funded premium subsidies).

These inflationary rebates are referred to as “price protection” in the Senate Finance Committee’s reporting on PBMs, which also found that manufacturers have often managed to increase their list prices when necessary without incurring penalties under their PBM contracts:

“Price protection terms vary from contract to contract. For example, they can cap the annual increase of a drug’s WAC price increase (i.e. prior to rebates) or its net price (after rebates). The Committee found examples of annual price caps ranging from 0% to 12% in one contract alone. The Committee’s investigation also found examples of manufacturers seeking to and succeeding in efforts to avoid paying these additional rebates by timing their WAC price increases to exploit the terms in PBM contracts.”

The Committee’s report does not always hit the mark – in fact, it often assumes that every kind of private actor in the insulin market is to blame for the high costs a portion of patients on insulin pay for their medicine. However, the Committee’s report does contain some important takeaways for consumers and taxpayers.

Finally, PBMs reduce costs for consumers, plan sponsors, and taxpayers by engaging in (sometimes controversial) utilization management and medication adherence efforts that are meant to control costs for the plan sponsor and/or client and achieve better health outcomes for the plan beneficiaries. Such tactics include prior authorization, step therapy, and drug utilization review or DUR.[6]

How PBMs Increase Costs for Consumers and Taxpayers

While PBMs decrease prescription drug costs for consumers and taxpayers in a number of ways outlined above, there are also a number of ways they increase health care costs.

First, and as noted above, three separate industry analyses indicate the global PBM market was valued at between $467 billion and $495 billion in 2022, and could grow to around $750 billion by 2030. That is hundreds of billions of dollars siphoned away from consumers, taxpayers, manufacturers, pharmacists, and other stakeholders in the health sector and towards PBMs. To the extent that revenue earned by PBMs exceeds their costs for providing services, PBMs are making profits that should be closely examined by policymakers when tax dollars are at stake. (Meddling in the profits and practices of PBMs in the private sector is a separate matter.)

Second, there is compelling evidence that PBM consolidation and corresponding pressures to extract larger rebates from manufacturers are putting upward pressure on drug list prices. Higher drug list prices can lead to higher premiums in the private sector (when PBM administrative fees are tied to list prices), associated premium subsidies (through the ESI exclusion, ACA premium subsidies, and Part D subsidies), and consumer out-of-pocket costs (when OOP liability is tied to list prices).

The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) noted in recent comments to the FTC that list price incentives in the current PBM business structure can reduce access to generic and biosimilar medications, which are often less expensive for plans, taxpayers, and consumers than their brand-name reference product:

“While it may be appropriate for PBMs to work to negotiate lower prices through the use of a formulary, the preference for highly rebated products and/or products with high WAC-based specialty pharmacy fees often imposes higher net costs on patients at the pharmacy and limits patient access to lower cost generics and biosimilars.”

Third, as reported by CBO, PBM consolidation may lead to higher fees above and beyond the impact higher list prices have on PBM fees:

“…PBMs probably use their increased leverage when negotiating with insurance plans over contract terms to charge higher fees to plans (which could take the form of PBMs keeping a larger fraction of rebates). The insurance plans then pass some share of those higher costs on to consumers in the form of higher premiums.”

The above paints a mixed picture, one in which PBMs increase efficiencies and reduce taxpayer and consumer costs in some cases, and increase consumer and taxpayer burdens in other cases. Unfortunately, many of the distortions in place throughout the pharmaceutical supply chain today are a result of bad government policies – some that have been in place for decades and are difficult to reform or replace.

How Government Distortions Affect the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

Medicaid

The Senate Finance Committee’s bipartisan 2021 report on insulin prices indicated that Medicaid’s statutory drug rebates induced manufacturers to set higher list prices for their new prescription drugs:

“...the MDRP [Medicaid Drug Rebate Program] may influence drug spending outside of Medicaid by leading some drug manufacturers to inflate their launch prices and avoid setting new and lower ‘best prices’ for their products.”

Federal law already heavily sets the price of prescription drugs in Medicaid by requiring manufacturers to rebate to federal and state governments a significant portion of their average drug price charged to wholesalers. The typical rebate amounts are:

- 23.1 percent of the average manufacturer price (AMP) for brand-name drugs;

- 17.1 percent of AMP for brand-named drugs “approved exclusively for pediatric indications [and] certain clotting factors;” and

- 13 percent of AMP for generic drugs.

Most drugs are also subject to rebates if the manufacturer increases their list price faster than inflation.

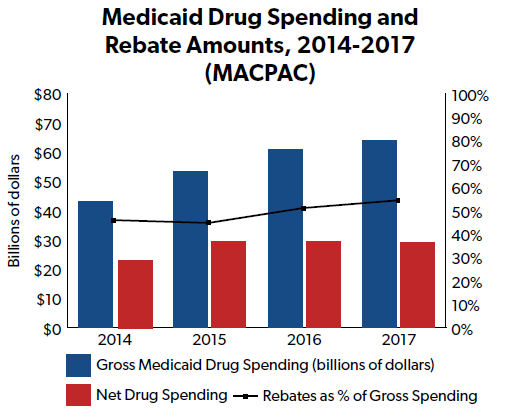

The result is that both statutory rebates and additional drug rebates negotiated by states and their contractors in Medicaid cut the pre-rebate price of prescription drugs for Medicaid by more than half.

According to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), gross drug spending in Medicaid in fiscal year (FY) 2017 (the most recent year data is available) was $64 billion but net spending after rebates was only $29.1 billion. That means rebates reduced the gross price of prescription drugs in Medicaid by more than 54 percent.

While that may sound like a good deal for taxpayers, NTU has long warned that when statutory price controls reduce the price of a good far below the cost of developing, manufacturing, and distributing that good, manufacturers will seek to push that cost bubble onto other payers or customers.

Evidence indicates manufacturers may be pushing the cost bubble onto private insurance and taxpayers through higher list or ‘launch’ prices for new products. This affects PBM revenue streams, since many private-sector administrative fees earned by PBMs are based on list price, and consumers, who often pay an out of pocket share based on list prices.[7]

340B

According to GAO, the 340B Program:

“...requires drug manufacturers to sell outpatient drugs at discounted prices to covered entities—certain hospitals and recipients of certain federal grants—in exchange for having their drugs covered by Medicaid. To be eligible for the 340B Program, hospitals must meet certain requirements intended to ensure that they perform a government function to provide care to low-income, medically underserved individuals.”

Per both Kaiser Health News and the American Hospital Association, 340B discounts are typically 25 percent to 50 percent of what a participating hospital would otherwise pay for a prescription drug.

The program has grown in size significantly over the past several years. For example, the number of hospitals participating in 340B grew 16 percent from 2015 to 2019 (from 2,170 participating hospitals to 2,523 participating hospitals) and drug purchases under the program grew sixfold from 2009 ($4 billion) to 2018 ($24 billion).

GAO has expressed concerns about the growth of the program and the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) oversight of 340B. The non-partisan government watchdog recommended in 2018 that HRSA and hospitals take action to prevent drug discounts that improperly duplicate those in MDRP. GAO has also issued recommendations related to the extraordinary growth in participating hospitals under 340B, to make sure all facilities utilizing the 340B Program are continually eligible to do so.

In a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), several academic authors noted that “most favored nation guarantees (MFNs)” like those in the 340B Program:

“...threaten formulary efficiency by introducing a contracting externality. If one PBM secures a lower net price for a branded drug through aggressive formulary incentives, the drug maker must also lower the net price for the other PBMs who have MFN guarantees. The result is an equilibrium in which PBMs operate with muted formulary incentives and market efficiency is reduced.”

The authors also wrote that the 340B Program is arguably “more important than the Medicaid MFN, because many more drug purchases are currently entitled to 340B discounts than Medicaid rebates.”

To the extent that the 340B Program causes manufacturers to take a loss on the sale of their products, or even significantly reduces profits available to invest in research and development (R&D), the 340B Program like MDRP pushes the cost bubble of developing, manufacturing, and distributing drug products onto other payers and stakeholders in the health care sector.

The recent explosive growth of the 340B Program, especially providers’ use of contract pharmacies, has direct financial implications for PBMs as well.

According to a 2021 report from the Drug Channels Institute, a “leader in pharmaceutical economic analysis,” pharmacies that are owned by or contract with major PBMs are accounting for an increasing portion of contract pharmacy relationships in the 340B Program.

For example:

“…companies with retail pharmacies account for more than two-thirds of the 340B program’s total contract pharmacy locations. These companies include Walgreens, CVS Health, Walmart, Rite Aid, Kroger, and Albertsons.”

CVS Health, of course, is owned by the same parent company as the largest PBM, CVS Caremark. And, per Drug Channels Institute, “Walgreens and CVS Health remain the two most active 340B contract pharmacy participants.”

However, the two other large PBMs that are not vertically integrated with a national pharmacy also have a significant presence in the 340B Program:

“The two large PBMs that lack retail pharmacies—the Express Scripts business of Cigna and the OptumRx business of UnitedHealth Group—are among the most active participants when measured by the number of 340B contract pharmacy agreements with covered entities.”

And non-retail settings like mail-order pharmacies and specialty pharmacies are also increasingly important to the PBMs’ 340B lines of business. Drug Channels reports that “the big three PBM’s non-retail pharmacies account for only 0.5% of 340B contract pharmacies—but 18% of 340B contract pharmacy relationships.”

Together, these two programs (MDRP and 340B) likely create powerful distortions in the prescription drug market that contribute to high list prices, which can adversely affect consumers and taxpayers through higher out-of-pocket costs and higher premiums.

Affordable Care Act (ACA) Mandates

Arguably the most significant development in PBM business practices during the 2010s was the shift from open to close formularies, as noted above in our overview of PBM history. The bipartisan Senate Finance Committee report from 2021 indicates that the increased regulations and insurer mandates from the Affordable Care Act (ACA) played a significant role in PBMs’ switch to closed formularies, which has had consequences for patient access and drug costs:

“…Sanofi also faced increased pressure from its payer and PBM clients to offer more generous rebates and price protection terms or face exclusion from formularies, developments that were described as ‘high risk for our business’ that had ‘quickly become a reality.’ These insurance market changes were partly driven by the implementation of the ACA, which put pressure on plan margins, and a willingness by plans to exclude drugs from their formularies as a negotiating tool.”

And later in the Senate Finance report:

“The [Sanofi] memo also laid out some of the ACA provisions that provided the government additional regulatory power over the private health care market that likely resulted in increased costs to health plans and more restrictive formularies.”

Closed formularies have had significant direct impacts on patients and consumers (reduced access to drug products) and indirect impacts on consumers and taxpayers (by putting financial pressure on insurers, altering the nature of private sector PBM-manufacturer negotiations, and potentially incentivizing higher list prices as a response to closed formularies).

The ACA’s responsibility in squeezing insurers’ cost bubble onto other payers in the health care sector – including consumers paying premiums and copays and taxpayers subsidizing health programs – deserves closer examination by Congress. Further examination of ACA dynamics would require a much lengthier discussion beyond this paper.

Taxpayer-Friendly PBM Reform - 6 ‘Dos’

Spread Pricing Transparency

While NTU would not support requiring insurers, PBMs, manufacturers, and pharmacists nationwide to open up their books and disclose all privately negotiated rates to the federal government, we do believe increased transparency around spread pricing practices of PBMs is appropriate when taxpayer dollars are directly on the line (i.e., in Medicaid and Medicare).

As noted above, spread pricing appears to be a limited problem in the Part D program.[8] Federal policymakers in Congress and at CMS should monitor the prevalence of spread pricing in Medicare going forward, but that should not be the primary focus of spread pricing transparency efforts.

Instead, where federal law could increase transparency around spread pricing practices is in Medicaid programs, jointly managed by federal and state governments.

The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) noted in 2019 research that investigations by state government agencies in Ohio, Massachusetts, and Michigan found PBMs managing those states’ Medicaid programs engaged in significant spread pricing:

- “In 2018, a report by Ohio’s state auditor found that PBMs cost the state program nearly $225 million through spread pricing in managed care”;

- “Similar analysis by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission found that PBMs charged MassHealth MCOs more than the acquisition price for generic drugs in 95% of the analyzed pharmaceuticals in the last quarter of 2018”; and

- “Michigan found that PBMs had collected spread of more than 30% on generic drugs and a report found that the state had been overcharged $64 million.”

For more details on how state governments are considering and implementing PBM reform, please consult Appendix D, “State Governments and PBM Reform,” by NTU Director of State Affairs Jess Ward.

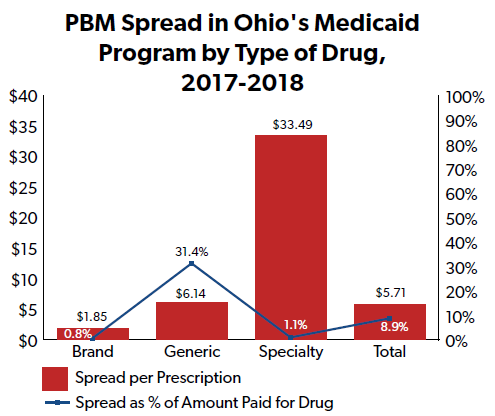

Ohio’s state auditor report found that the spread in their Medicaid program averaged $5.71 per claim, and made up 8.9 percent of drug spending amounts overall. For generic drugs in particular, PBMs in Ohio’s Medicaid program achieved a $6.14 per claim spread (accounting for 31.4 percent of generic drug spending amounts). In other words, PBMs disproportionately targeted generic drugs in their spread pricing practices.

An “independent vendor” the state of Ohio contracted with to assess PBM spread pricing indicated that just a third of that average spread would have covered PBMs’ costs.

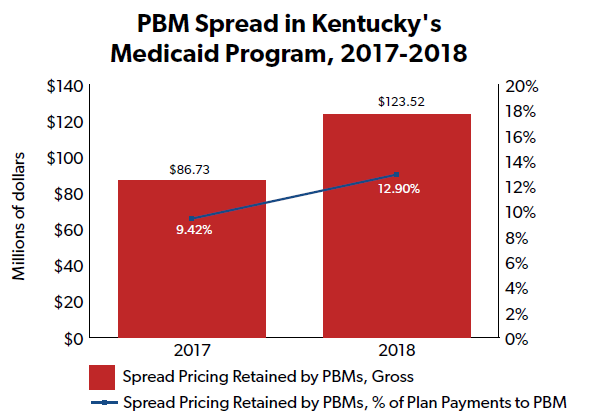

A similar report issued by Kentucky’s health agency around the same time indicated that PBMs were retaining a significant portion of revenue in the state’s Medicaid program through spread pricing practices.

Kentucky found that, in both 2017 and 2018, a majority of prescriptions in Kentucky’s Medicaid program were filled “using a spread pricing model” by one of two PBMs: CVS Caremark and Express Scripts. In 2018, more than $1 of every $8 paid by the state to the PBMs on spread pricing contracts – or $123.5 million out of $957.7 million total – was “not paid to pharmacies and kept by the PBMs as the spread.”

The Kentucky agency also expressed “concern that spread pricing is not correctly accounted for in the state’s medical loss ratio (MLR),” given the “lack of transparency” around spread pricing.

Finally, an extensive Bloomberg investigation released in 2018 indicated that PBM spread pricing had a disproportionate impact on generic drugs in Medicaid:

“...Bloomberg examined the prices of 90 of the best-selling generic drugs used by Medicaid managed-care plans. In 2016, the drugs made up a large portion of Medicaid’s spending on generics. … For the 90 drugs analyzed, which includes more than 500 dosages and formulations, PBMs and pharmacies siphoned off $1.3 billion of the $4.2 billion Medicaid insurers spent on the drugs in 2017.”

While spread pricing differentials may be a negotiable source of revenue for PBMs’ private lines of business, or affecting MLRs, policymakers should exact greater scrutiny when it comes to spread pricing that costs taxpayers. The investigations in Ohio and Kentucky – and the experience of other states like Massachusetts and Michigan – indicates that PBMs are collecting significant revenue via spread pricing in Medicaid programs, sometimes in amounts that well exceed their administrative costs per claim and a profit margin that aligns with other PBM lines of business.

Sens. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) and Chuck Grassley (R-IA) have proposed legislation to ban all PBMs from spread pricing, in their public and private lines of business. NTU believes that this is currently a bridge too far, given it would disrupt negotiations between PBMs, plans, manufacturers, and pharmacies in their private lines of business.

Reps. Buddy Carter (R-GA) and Vincente Gonzalez (D-TX) have proposed legislation to ban spread pricing in Medicaid only. Such legislation could be of merit should PBMs continue to abuse taxpayer dollars in Medicaid programs – via spread pricing that is many multiples beyond their cost of doing business plus a level of profit that aligns with other PBM lines of business – or if subsequent investigations by state and federal policymakers indicate that the PBM spread pricing problem in Medicaid stretches beyond a few states.

For the time being, NTU advises a more incremental but still impactful approach: let state Medicaid programs see how much in taxpayer dollars (and/or health plan savings) they may be losing to spread pricing. State lawmakers and Medicaid plan managers should not have to conduct expensive, lengthy audits to understand spread pricing and its impact on state (and federal) taxpayers funding Medicaid programs.

Federal policymakers could accomplish this aim by requiring PBMs to regularly report to state Medicaid programs on the scale and scope of their spread pricing in Medicaid, and to send such reports to CMS for federal oversight purposes. GAO, or the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) inspector general could provide an additional federal layer of oversight and reporting on the use of spread pricing throughout all 50 states. CMS and the state agencies managing Medicaid programs should have full visibility on potential program savings lost to spread pricing.

GAO noted that reporting requirements have contributed to the lack of spread pricing in Medicare Part D (see footnote 8), suggesting that similar requirements in Medicaid could discourage the use of excessive spread pricing by PBMs in Medicaid programs. And transparency could discourage these distortive business practices in a less disruptive manner than banning spread pricing in the public and private sectors. (Banning spread pricing in the private sector could even have the opposite of policymakers’ intended effect, squeezing the cost bubble on PBMs and inducing them to increase fees charged to public and private payers, PBM retention of rebates, and other cost increases for plans, consumers, and taxpayers.)

Federal policymakers could also consider providing more information on spread pricing in the Medicaid program to manufacturers, plan sponsors, and pharmacies (i.e., other private-sector participants in the pharmaceutical supply chain). Such transparency could ensure all parties have more information at their disposal in negotiations over fees. However, Congress and/or CMS must craft such policies carefully so as not to put their thumb on the scale for either manufacturers, pharmacies, or PBMs and plans in exclusively private-sector negotiations.

Reporting on the Use of Specialty Pharmacies

According to the National Association of Specialty Pharmacies (NASP), a specialty pharmacy:

“...is a state-licensed pharmacy that solely or largely provides medications for people living with serious health conditions requiring complex therapies. … [w]ith the average monthly cost [of specialty drugs] being $2500-$3500, complexities associated with the management of these diseases and their medications, and the increased focus on specialty drug development for ultra-orphan and orphan disease states, specialty pharmacy has become the new pharmacy.”

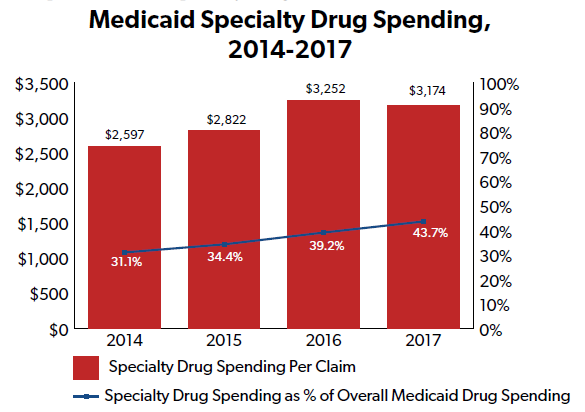

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) use specialty pharmacies to help manage specialty drug delivery, utilization, and spending for their customers (both plans and patients). Cost and utilization management of specialty drugs is becoming more and more important for consumers and taxpayers, as specialty drug spending makes up a larger and larger portion of total drug spending.

Specialty drug management is an important part of the PBM business model across public- and private-sector lines of business. For just one example, OptumRx – one of the three largest PBMs in the nation – indicated on their 2022 10-K report with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that $45 billion of the $112 billion they managed in pharmaceutical spending was for specialty pharmaceuticals.

Just as specialty drug spending and specialty pharmacy use are of importance to PBMs’ business model, they are also important to taxpayers’ prescription drug spending in Medicaid and Medicare.

According to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), specialty drug spending is driving drug spending growth in Medicaid:

“Magellan, a large, national pharmacy benefits manager (PBM), reported that for its contracted Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) populations, net spending per claim (net of federal and supplemental rebates) decreased 5.1 percent for its traditional drug classes but increased 20.5 percent for its specialty drug classes from 2015 to 2016.”

And specialty medications accounted for more than 40 percent of all Medicaid drug spending in 2017, according to PBM Express Scripts.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC; not to be confused with MACPAC above) reported in 2017 that, in 2014, “2% of Part D specialty-tier prescriptions accounted for 16% of Part D spending.”

MedPAC notes that “[a]ll major PBMs own specialty pharmacies,” leading to a potential conflict of interest where PBMs are responsible for 1) managing pharmacy spending for plans (and taxpayers) on the one hand, and 2) “expand[ing] specialty pharmacy revenues” on the other.

MedPAC suggests that these potentially-competing incentives could put upward pressure on costs in the Part D program. Unfortunately, MedPAC, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and other stakeholders in the pharmaceutical supply chain suffer from a lack of visibility and transparency on PBMs’ use of specialty pharmacies.

“Rebates and fees received by subsidiaries (e.g., specialty pharmacies) are not reported,” according to MedPAC. Additional data transparency and disclosure could reduce information gaps and enable both plan sponsors and CMS to make more cost-efficient decisions when it comes to partnering with PBMs.

As noted above, spread pricing transparency could also help reduce taxpayer burdens caused by PBMs in the specialty drug and pharmacy space. The Ohio auditor report mentioned above indicated that PBM spread in the state’s Medicaid program was $33.49 per specialty claim, many multiples higher than the spread per generic claim ($6.14) and per brand claim ($1.85).

Finally, AAM has noted that the increasing use of specialty pharmacies by PBMs – especially those owned by the parent entity of the same PBM – can create perverse incentives for both brand-drug selection and higher list prices since specialty pharmacy fees are often tied to list prices rather than net prices:

“…the use of vertically integrated specialty pharmacies introduces yet another incentive for PBMs to prefer higher list price drugs, as many specialty pharmacy fees and services charged to manufacturers are calculated based on a percentage of the inflated Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) of these products.”

Such perverse incentives can raise costs for taxpayers and consumers.

To the extent PBM spread pricing is a contributor to foregone consumer and taxpayer savings in Medicaid and in Medicare Part D, a combination of spread pricing transparency and enhanced specialty pharmacy reporting could enable private plan sponsors and public health program managers to recapture some of those savings for consumers and taxpayers.[9]

Strengthening Public-Private Negotiations

State and federal governments are in a rare spot when they are the ones with less information and leverage in a contract negotiation than their counterparts in the private sector.

After all, governments are responsible for enforcing national and state laws and regulations, and hold the power to punish, fine, jail, or tax offenders. The latter dynamic is starkly illustrated by the Inflation Reduction Act’s new prescription drug price-setting requirements in Medicare Part D, which are deemed “negotiations” but are backed up by a 95-percent gross sales tax on manufacturers that refuse the federal government’s terms and conditions.

How is it, then, that CMS and some state agencies – along with some private employers and plan sponsors – have achieved such poor leverage against PBMs in public-private negotiations over the management of Medicare and Medicaid drug spending?

PBM consolidation likely plays some role. As noted by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office: “[c]onsolidation within the pharmacy-benefit-management industry has also increased the leverage that PBMs wield in negotiating on behalf of their client insurers.” Though federal requirements (from reporting to formulary coverage mandates) limit the leverage PBMs can exercise over consumers and taxpayers, consolidation is no doubt a factor for public and private stakeholders attempting to manage drug and drug plan spending in Medicare and Medicaid. The next section explores how Congress could remove barriers to increased competition in the PBM sector.

Transparency and reporting – covered in a narrow fashion above, in regards to specialty pharmacies in Medicare Part D – also plays a role in PBMs potentially gaining an upper hand over the government in negotiations over Medicare and Medicaid services.

The bipartisan 2021 Senate Finance Committee report found that even plan sponsors were lacking in information and data from their PBMs regarding the “complex relationships” between the two parties. The Committee pulled the following quote from a 2011 Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (HHS OIG) report:

“Five sponsors had limited information about the rebate contracts and the rebate amounts negotiated by their PBMs. One PBM reported that it does not share the manufacturer rebate contracts with its sponsors because they contain confidential information and there is a chance that the sponsor may one day become a PBM itself. Another PBM specifically stated that the sponsor would ‘not be permitted to copy or retain’ any portion of the contract. As a result of these practices, most of the selected sponsors were unaware of all of the contract terms that determine the rebates they receive from drug manufacturers.”

Federal law allows for the “dissemination of price and rebate information that companies disclose to the Federal government for Medicaid and Part D plans” to HHS, GAO, CBO, state governments managing Medicaid, MedPAC, and MACPAC. Congress could consider adding to this list, reporting price and rebate information to Part D plan sponsors, Medicaid managed care plan sponsors, wholesalers, distributors, pharmacies, and other stakeholders in the pharmaceutical supply chain. Lawmakers could require the aggregation of data and the removal of sensitive business information to avoid putting their thumb on the scale for one private party over another private party.

Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-VA) provides for such confidentiality in her bipartisan Improving Transparency to Lower Drug Costs Act (H.R. 3682), which would require CMS to publicly disclose PBM “rebates, discounts, direct and indirect remuneration fees, administrative fees, and price concessions” on a publicly available website. Providing this information to the public may create more headaches that it solves – public misinterpretations or false assumptions concerning such data could lead policymakers down some dangerous rabbit holes – but Congress could, as a middle-ground approach between current law and the Spanberger proposal, consider expanding the universe of pharmaceutical supply chain stakeholders with access to PBM data as it pertains to the federal health programs.

Some extension of reporting requirements to private employers or plan sponsors may also be in order. The American Benefits Council has commented to the FTC that:

“The current rebate structure used in the marketplace is complex and opaque for many employers, making it hard for employers, as well as plan participants and beneficiaries, to understand the true prices and value of drugs.

…Increased availability of cost information could help employer plan sponsors and their employees make better informed purchasing decisions that result in higher value pharmacy expenditures.”

Extension of PBM reporting to private entities should be managed with care, balancing the need to reduce complexity and opacity in the pharmaceutical supply chain with the sensitive and confidential nature of some PBM business information.

That said, previous work by CBO indicates that increased transparency for private employers and plan sponsors could reduce health care costs. According to CBO’s score of Sec. 306 of the 2019 Lower Health Care Costs Act, which was never enacted but would have imposed new information reporting requirements on PBMs and for the benefit of group health plans:

“CBO expects that those provisions would allow some plan sponsors to better evaluate the trade-offs among contract provisions and could lead to more efficient competition among PBMs.

…After accounting for [the] higher fees [assessed by PBMs to recoup lost income], CBO estimates, on net, section 306 would initially reduce plan costs by roughly 1 percent for prescription drugs across all plans in the private health insurance market.”

CBO found that, in turn, premium growth would slow relative to current law projections, and that employers would instead pay higher wages. Since wages are taxable but most employer insurance premiums are not taxable, reduced premiums under Section 306 would lead to higher federal revenues, reducing federal deficits over the course of 10 years.[10]

One actor that should probably not automatically receive sensitive PBM data is the FTC, which has taken a ‘guilty until proven innocent’ approach to the PBM industry as of late. The PBM Transparency Act of 2022, from Sens. Maria Cantwell (D-WA) and Chuck Grassley (R-IA), would have required PBM reporting on fees and spread pricing that could be of use to CMS, states, and the pharmaceutical supply chain, but could be dangerous in the hands of an anti-free market FTC.

Explore Industry Disruptors

While the market prominence of the three largest PBMs today – CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx – may seem like it will last for years or even decades to come, unique and innovative competitors are looking to disrupt the industry and compete with these entities.

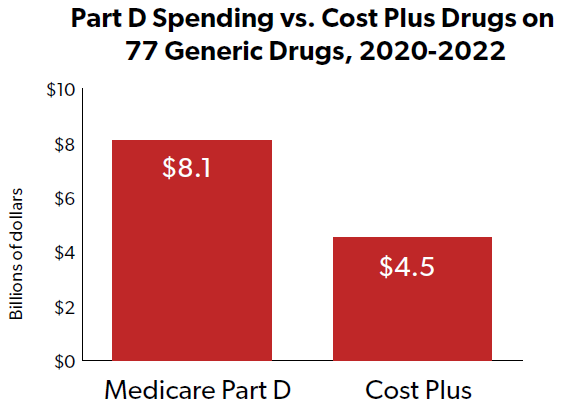

In October 2021, two new PBMs launched at the same time that promised to disrupt the practices and procedures of the major incumbents. EmsanaRx was “designed to offer employers greater clarity into pricing for pharmaceuticals [i.e., more transparency] and will set a fixed price per prescription [i.e., fixed fees].” Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company launched a PBM “aim[ing] to sell generic drugs at a transparent, fixed rate, and to achieve this united manufacturing, distribution and pharmacy services under one roof.”

In addition to EmsanaRx, the smaller PBM Navitus – owned by major retailer Costco – is “pass[ing] through to employers 100 percent of the drug discounts negotiated with manufacturers” according to the Commonwealth Fund. The same report notes Amazon is “market[ing] pharmacy services directly to consumer.”

With all this competition, what could stand in the way of these disruptors gaining market share in the PBM industry? To start, overzealous legislation and regulation from the federal government.

Rite-Aid, for example, owns a smaller PBM (Elixir) that is aiming to compete with the top three. In its latest 10-K report with the SEC, Rite Aid sounded an optimistic note about customer and client demand for PBM competition:

“Plan sponsor clients of PBMs are seeking new and innovative solutions to manage pharmacy benefit costs. Certain market segments, such as regional health plans, union/municipal plans, and certain mid-market employers are seeking viable alternatives to the ‘Big 3’ PBM providers.”

However, Rite-Aid also warned that overzealous federal and state regulation could impact its efforts to compete, including but not limited to:

- A 2021 federal appeals court ruling that held “a North Dakota state law could regulate certain aspects of PBMs’ participation in Medicare Part D,” despite traditional federal preemption of such state laws and regulations in Medicare;

- Potential future court rulings that could undo the federal government’s long-standing preemption over the regulation of private health insurance, which could open the floodgates to a patchwork of state laws and rules; and

- Price controls in the just-enacted IRA that “could have a spillover effect in the commercial market, negatively impacting … PBM revenue and retail pharmacy reimbursement in the commercial market.”

According to 10-K reports from some of the major incumbents in the PBM industry, federal and state regulations also limit:

- Pharmacy network management;

- Development of maximum allowable costs for prescription drugs;

- The administration of benefits;

- The development of tiered formularies;

- Standardization of products and services across state lines.

Policymakers in Congress and at the federal agencies should be asking themselves: to what extent do current health rules and regulations – and future, proposed rules and regulations for the federal health programs and for the private sector – result in a sort of regulatory capture for the three strongest PBMs, allowing them to maintain market share or even capture additional market share?

Both the incumbents and the disruptors in the PBM field note that laws, proposed legislation, regulations, proposed rules, and court rulings at the federal level and in the states increase the costs of doing business. Congress should invite the industry disruptors to Washington, D.C. – whether in private meetings, public hearings, or both settings – to hear from them about the legislative and regulatory barriers to business development. Incumbents, based on their longer experience in the market, could have valuable perspectives as well. If there are opportunities for lawmakers to permit the market to function more efficiently, they should explore such reforms in the 118th Congress.

Promising models of public-private partnerships that have worked in the past can be found in Appendix C, “Case Studies of What Works.”

Explore the “Reverse Auction” Model

Model legislation pioneered by New Jersey’s public employee benefits program in 2016 and adopted by several other states since then could provide a model to federal policymakers and/or private employers and plans in the future.

According to the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), the organization that helped pioneer the model legislation in New Jersey:

“A 2016 New Jersey law gave the state flexibility to share bid information submitted by all pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in order to incentivize the PBMs to submit lower offers in additional rounds of bidding – a process known as a reverse auction. While reverse auctions have been used historically to procure goods, New Jersey’s first-in-the-nation PBM model represents a new way states can procure services and save millions on prescription drug spending.”

The basic idea behind a reverse auction is that the state sets many of the terms of service a PBM would have to agree to in order to do business with the state – for example, formulary development and cost sharing rules – and only compete on price. Anonymized bid prices are revealed to the PBMs competing for the state’s business, and subsequent rounds of bidding attempt to drive the price down even further until the state (and its taxpayers) get the best deal. NTU has supported similar models for funding clean and green energy projects, as an alternative to increasingly costly taxpayer subsidies.

After New Jersey reported a projected $2.5 billion in savings for their state employee health plan between 2017 and 2022, other states began to follow New Jersey’s suit. Policymakers in Maryland, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Maine, Colorado, Louisiana, and Minnesota have considered implementing similar reverse auction policies or have already done so. A potential additional benefit for states is that they procure PBM services faster – according to NASHP, “[t]raditional PBM procurement typically takes six months, but New Jersey’s reverse auction PBM selection process took less than two months.”

Federal policymakers should explore if and how New Jersey’s model can be adopted to state Medicaid programs or to Medicare. Federal proposals would have to be carefully designed so as not to mandate reverse auctions, but instead offer them as an additional tool in plans’ toolkits to reduce costs borne by consumers and taxpayers. Policymakers should also collaborate with private employers and plan sponsors to determine what legislative and regulatory factors, if any, stand in the way of private entities adopting the reverse auction model.

Reduce Medicare COIs With PBMs’ P&T Committees

Since 2013, the Inspector General for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS OIG) has recommended that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) clarify that someone with ties to a PBM serving on that same PBM’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee could represent a potential conflict of interest, or COI. Right now, individuals with ties to drug manufacturers or plan sponsors are considered having potential COIs in serving on a P&T committee, but individuals with ties to a PBM are not considered as having a potential COI.

This recommendation has still not been implemented at CMS, nearly 10 years after HHS OIG first identified an issue.

A P&T committee is generally developed by a PBM and helps inform formulary development and placement. Or, as Pharmacy Times puts it:

“The P&T committee is an independent entity that is comprised of anywhere from 10 to 15 members. The committee is primarily made up of physicians and pharmacists, but can also include nurses, administrators, legal experts, and economists.

The P&T committee develops, manages, and updates the formulary for the PBM, as well as developing policies to ensure safe and effective drug use.”

HHS OIG pointed out in a 2013 report that CMS regulations “specify only” that a COI involves “direct or indirect financial interest” with a drug manufacturer or plan sponsor. PBMs, despite the vertical integration of several major PBMs with plan sponsors, are excluded from the CMS definition of potential COIs.

HHS OIG found that “[o]f the 22 P&T committees maintained by PBMs, more than two-thirds reported that they did not define any financial interests in PBMs as conflicts.” Doing so is voluntary at this point, but the lack of any COI policy is troubling for patients, consumers, and taxpayers affected by P&T committees’ formulary decision-making. Formulary development affects not only patients’ access to drug products, but the prices consumers and taxpayers bear for certain products.

HHS OIG recommended:

“CMS should define PBMs as entities that could be affected by drug coverage decisions. CMS should require the P&T committee members, who must be free of conflict with sponsors and pharmaceutical manufacturers, to also be free of conflict with any PBM that manages a sponsor’s prescription drug benefit.”

For nearly 10 years, it appears CMS has refused. Their initial disagreement with this recommendation, in 2013, somewhat absurdly claimed that “PBMs do have an interest in formulary decisions”:

“CMS did not concur with our first recommendation, that it define PBMs as entities that could benefit from formulary decisions. CMS asserted that its formulary review process provides the appropriate protections from any adverse effects of conflicts of interest. CMS noted that PBMs do have an interest in formulary decisions because they negotiate price concessions on behalf of sponsors as their subcontractors.”

HHS OIG disagreed with CMS’s interpretation of PBMs’ potential financial conflicts of interest in the development of P&T committees and formularies, and this unimplemented recommendation was outstanding as of October 2021.

If CMS continues to refuse to implement OIG’s long-standing recommendation, Congress could step in and clarify the COI policy for P&T committees itself.

Less Promising Proposals at the Federal Level

Mandatory Point-of-Sale Rebates

Some policymakers, including former President Donald Trump, have advocated for mandating that PBMs pass all manufacturer rebates on to consumers at the point of sale. This is a tempting path for some, including federal officials who have advocated for free markets. The thinking goes that it’s only fair to ensure that the savings from a rebate negotiated for a particular product go directly to the customer who uses that product.

However, NTU believes that proponents of this policy (and non-partisan budget scorekeepers) have yet to demonstrate that such a proposal would deliver robust and consistent savings to taxpayers and consumers writ large.

CBO confirmed as much when it scored the budgetary impacts of former President Trump’s proposed ‘rebate rule,’ which would have required all rebates in Medicare Part D and Medicaid to be passed on to the consumer at the pharmacy counter.

CBO found, perhaps counterintuitively, that implementing that rule would “increase federal spending by about $177 billion over the 2020–2029 period.” This is because insurers would no longer be able to use rebates to reduce beneficiary premiums; premiums would go up as a result; and since the share of Part D premiums borne by taxpayers is a fixed percentage of total premiums, taxpayer spending on Medicare would increase.

Some states have passed laws requiring PBMs to pass rebates on at the point of sale. Federal policymakers should study how such laws affect premiums, out-of-pocket costs, and prescription drug prices in the states in question. Such state laws could serve as experiments for the potential consideration of similar policies at the federal level – a federalist exercise of sorts.

It is too early in the PBM reform space to recommend such a policy at the federal level, though, and future proponents must grapple upfront with the projected effects point-of-sale rebates would have on federal spending.

Total Ban on Spread Pricing

Spread pricing remains a concern in state Medicaid programs, and as noted above we believe federal policymakers should explore how to empower CMS, states, plan sponsors, and pharmacies to limit the use of spread pricing in the federal health programs. That said, we believe a nationwide ban on spread pricing – applying to the public and private sectors – is a step too far at this moment.

As discussed above, PBMs currently have several revenue streams at their disposal, including but not limited to:

- Retained rebates from manufacturers;

- Administrative fees;

- Clawbacks and fees from pharmacies;

- Spread pricing; and

- Fees assessed on manufacturers.

While it may be tempting to cut off one of those revenue streams in the public and private sectors, policymakers may not like the end results. The major PBMs, all of which are publicly traded and answer to investors, will ultimately seek to make up for lost revenue from a theoretical spread pricing ban with revenue from the other sources outlined above – or from new sources not yet contemplated by this paper. This could have the effect of actually increasing the costs that plans, consumers, and taxpayers bear for PBM services on net, or at least failing to decrease such costs.

In PBMs’ private lines of business, we believe increased competition is a better path forward to reduce the use of spread pricing. Pharmacies, manufacturers, and other stakeholders in the pharmaceutical supply chain may raise concerns about PBM spread pricing practices. If they have more options to take their business elsewhere – to PBMs that don’t engage in spread pricing – the market may provide a less disruptive end to the practice.

The Least Promising Proposals at the Federal Level

FTC Investigations and ‘Breaking Up’ PBMs

In June 2022, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) launched an inquiry into the PBM industry. While NTU is concerned about some of the PBM business practices outlined above – especially as they affect taxpayers and taxpayer-backed programs – we strongly believe that the FTC is the wrong venue to investigate and redress such business practices.

NTU wrote in May 2022 that new members of the FTC could spell trouble for taxpayers and consumers:

“...The agency sent threatening letters to companies warning them to merge at their own risk and has stated its intention in the 2022-2026 draft strategic plan to engage in social policy priorities. The current regime at the FTC has sought to undermine the consumer welfare standard and instead substitute its own judgment on what is best for consumers.

An aggressive FTC won’t just go after Big Tech, it will go after any company or industry deemed too large or consolidated by politicians and political appointees.”

And, more broadly, NTU has noted frequently in past research that an aggressive FTC can lead to “poorer economic performance, lower government revenues, and even more upward pressure on federal budget deficits”:

“...research has shown that increased periods of antitrust enforcement can lead to sector-wide declines in stock returns, often translating to poorer economic performance, lower government revenues, and even more upward pressure on federal budget deficits. Should risk-takers in the private sector pull back on developing new products and services under the yoke of FTC and the Antitrust Division, consumers suffer; meanwhile, incumbent companies, saddled with more regulatory costs, could raise prices at a time when high inflation seems less and less ‘transitory.’”

Indeed, the FTC’s current investigation into PBMs appears more like a ‘guilty until proven innocent’ fishing expedition than a sober inquiry into the machinations of the pharmaceutical supply chain.

The FTC is seeking loads of sensitive business information from the largest PBMs, including:

- Organizational charts;

- Personnel directories;

- All board of directors meeting minutes;

- All private contracts;

- Pharmacy reimbursement data for dozens of drug products;

- Spreadsheets identifying all company audits; and

- Information on all drug formularies in every plan under the company’s umbrella.

The information request alone will likely require thousands of labor hours and hundreds of thousands (or even millions) of dollars in legal and compliance burdens from the major PBMs, sucking time and revenue away from more productive activities (and, ironically, could lead to PBMs actually increasing fees charged to clients).

More importantly, pharmaceutical supply chain stakeholders should realize that this FTC will not stop their health sector investigations at the doorstep of PBMs. Once they finish naming, shaming, investigating, and regulating PBMs, they could turn their attention to any number of additional actors in the U.S. health care system – with the same ‘guilty until proven innocent’ approach they are taking with PBMs.

Similarly, NTU would oppose any efforts by the FTC or lawmakers to ‘break up’ the larger PBMs, or to force insurers to divest of (or spin off) their PBM businesses. To support such efforts would be to repeat the mistakes of the past, before antitrust regulators began broadly following the consumer welfare standard that has led to tremendous economic and consumer cost-of-living gains in the past half century or so.

Congress and even the federal regulators at CMS have several avenues with which to pursue PBM reform, but the FTC should not be part of the trip.

Government Interference in Private Sector Negotiations

A recent and concerning approach from some lawmakers in Congress has been to try and substitute private-sector negotiations over prescription drug costs with government price-setting.

Beyond the harmful price controls of the IRA – which every Republican lawmaker in Congress opposed – there are recent, bipartisan efforts that would insert the government into private-sector negotiations over insulin.

NTU previously wrote of the Improving Needed Safeguards for Users of Lifesaving Insulin Now (INSULIN) Act in the U.S. Senate:

“The Senate’s INSULIN Act essentially allows insulin manufacturers to voluntarily pledge to keep their list prices fixed to ‘not … greater than the weighted average of the Medicare Part D negotiated prices for such insulin, net of all manufacturer rebates, received by plans in 2021.’ That fixed price would apply to 2024, and in years after manufacturers could only increase their prices at the rate of inflation (measured by the consumer price index for all urban consumers, or CPI-U).

The INSULIN Act dangles a number of incentives before insulin manufacturers to convince them to essentially voluntarily fix their list prices:

- Insurers and PBMs would not be able to collect rebates or seek further price concessions from manufacturers for insulin products with fixed prices;

- Insurers would not be able to charge beneficiaries more than $35 per month out-of-pocket for those fixed-price products, and would not be able to require a beneficiary hit their deductible before applying the $35 per month limit;

- Insurers would not be able to use “utilization management tools, such as prior authorization or step therapy” to limit access to or coverage of fixed-price products other than for safety reasons.”

We noted that such legislation could rob consumers and taxpayers of the robust negotiations that – while sometimes flawed, due in large part to market distortions created by government and discussed earlier in the paper – largely help deliver savings to consumers on their premiums and at the pharmacy counter. Under the INSULIN Act, many manufacturers would lock in at the government-set price and reap the rewards of inflationary increases (at a time of persistently high consumer inflation) and government-protected price and coverage policies – regardless of competition in the manufacturer, PBM, plan, or pharmacy markets.

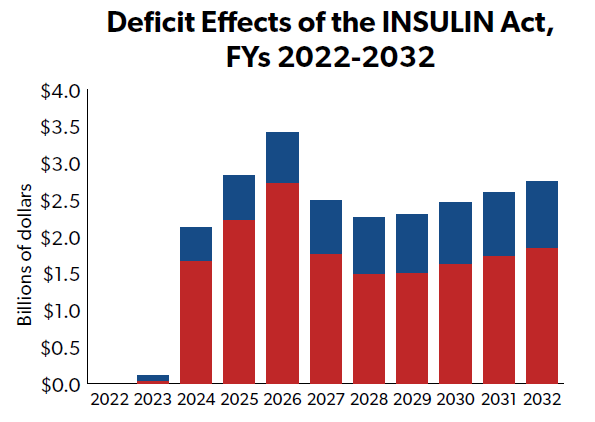

The bill, though likely well-intentioned, would ultimately 1) reduce prices for only a small number of patients using insulin, 2) increase federal deficits by more than $20 billion over 10 years, 3) raise premiums for many individuals in the private marketplace and in Medicare, and 4) actually increase the net price of insulin, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). CBO indicates that the bill’s price controls have the effect of squeezing the cost bubble for researching, updating, distributing, and delivering drugs to patients onto other, otherwise non-affected parts of the market.

It’s an example of how government interference in private-sector negotiations can lead to economic inefficiencies and increased taxpayer costs, and is not a model other lawmakers should seek to emulate.

Conclusion

In an earlier era of the American health care system, NTU believed PBMs held promise for consumers and taxpayers. Indeed, the theoretical mission of PBMs is promising, and plans and PBM industry disruptors should focus on this core mission in the years ahead: drive down plan, consumer, and taxpayer spending on pharmaceutical products through robust competition, private-sector negotiations, and utilization management.

Unfortunately, PBMs today have failed to fully live up to that core mission, and present numerous risks and challenges to consumers and taxpayers in the U.S. health system in 2023. Retained rebates, fees, and spread pricing in the Medicaid program are likely driving up state and federal costs beyond what they need to be for such services, while PBM practices in the private sector are incentivizing higher drug list prices and higher premiums – which increase consumer out-of-pocket costs and the burdens taxpayers bear for subsidizing employer-sponsored health insurance.

While these challenges are vexing, federal policymakers should still tread cautiously on reform and seek narrow, market-oriented solutions to the PBM problems taxpayers face. More reporting and transparency is the most promising path forward, followed by a close examination of the legal or regulatory barriers that could stand in the way of robust PBM competition.

Price controls and antitrust enforcement, on the other hand, would do more harm than good. Price controls in Medicaid and Medicare, along with increased insurance regulations through the Affordable Care Act, are part of the reason PBM practices present such a problem to taxpayers and consumers today. An aggressive Federal Trade Commission, meanwhile, may have their eyes trained on PBMs today, but when satisfied with investigating and regulating this industry they will no doubt move on to their next targets in the health care sector – possibly leaving consumers and the market worse off as a result.

Increased competition in the PBM industry could solve many of the problems policymakers identify today in the pharmaceutical supply chain, and fostering such increased competition – and, more importantly, not standing in the way of competition – should be Congress’ north star on PBM policy in the 118th session and beyond.

Appendix A: Pharmaceutical Spending in Context

As lawmakers consider policies that would affect pharmaceutical spending and payment policies, it is critical they consider pharmaceutical spending in context of America’s complex and expensive health care system.

Though the list (or ‘sticker’) price of certain pharmaceutical drugs has been the target of some lawmakers’ ire for years, pharmaceutical spending continues to make up a relatively small portion of the nation’s total annual spending on health care.

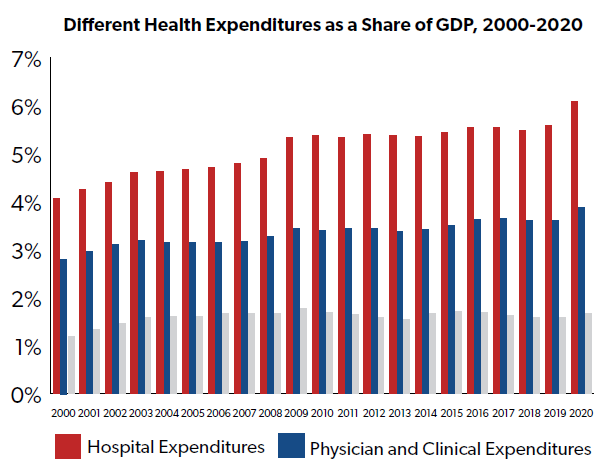

According to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), prescription drug spending made up only 1.67 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020. This is more than triple prescription drug spending’s share of economic output in 1970 (0.51 percent), but pales in comparison to total national health expenditures (19.74 percent in 2020), hospital spending (6.08 percent of GDP in 2020), and even physician spending (3.87 percent of GDP in 2020).

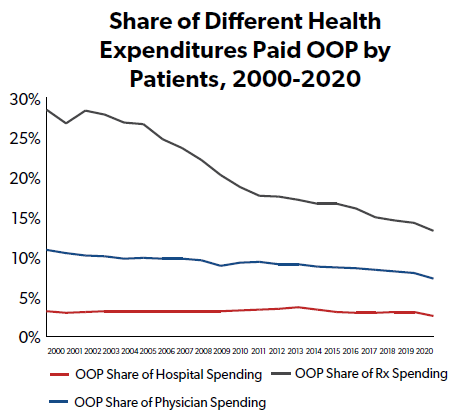

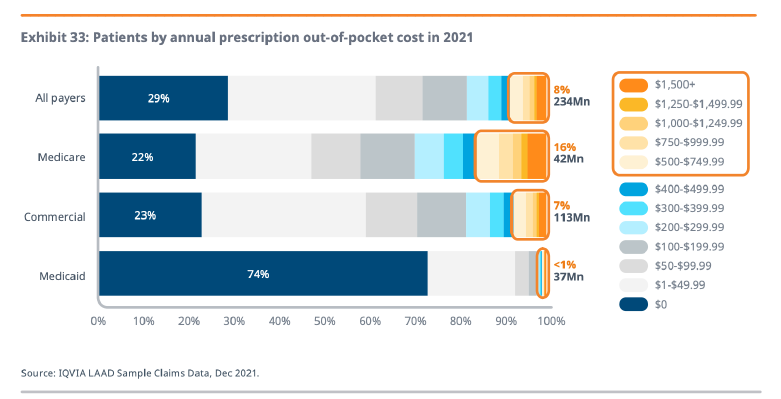

One reason that policymakers in Washington, D.C. may be so focused on prescription drug costs is because their constituents – American individuals and families – have historically paid a higher proportion of their prescription drug expenses out-of-pocket than other types of health expenses, such as hospital stays and visits to the doctor.

While hospital stays and physician charges have an outsized impact on national health spending (and on insurance plan premiums, because insurers cover a larger portion of those health expenses than prescription drugs), everyday consumers are less insulated from drug costs, which likely helps fuel outrage about the prices and costs of prescription drugs. Though the share of drug costs borne out-of-pocket (OOP) by consumers has fallen sharply since the early 21st century, the OOP share for drugs remains higher than that for hospital costs or physician costs.

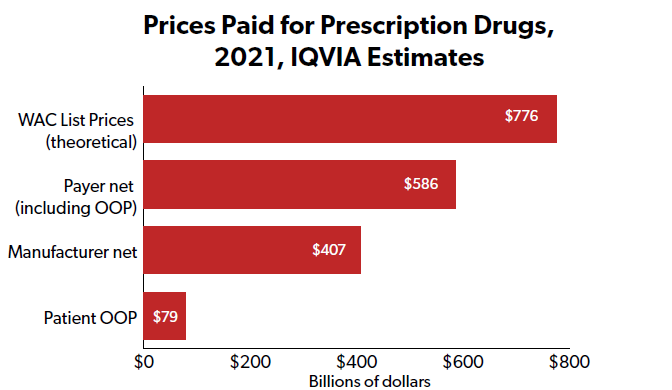

And while the list or ‘sticker’ price of a drug is generally what generates shocking headlines, and both consumer and policymaker outrage, the list price almost never reflects either a) what an insurer or the government pays for the drug, or b) what a patient pays out-of-pocket for the drug.

Recent data from IQVIA (published in April 2022) demonstrates that both net prices for drugs and out-of-pocket drug costs for consumers are mere fractions of total list prices, as measured by the wholesale acquisition cost for drug products.

IQVIA also reports that while net drug prices have increased in recent years – about $76 billion, or 23.4 percent over five years (an average of 4.7 percent per year) – more than half of the gross increase ($94 billion of $181.7 billion) is due to increased volume of brand-name drugs rather than new brand drugs coming to market ($87.7 billion of $181.7 billion). The gross increase of $181.7 billion in net manufacturer revenues is offset by $93 billion in revenue losses due to loss of brand exclusivity and the resulting generic competition.