(pdf)

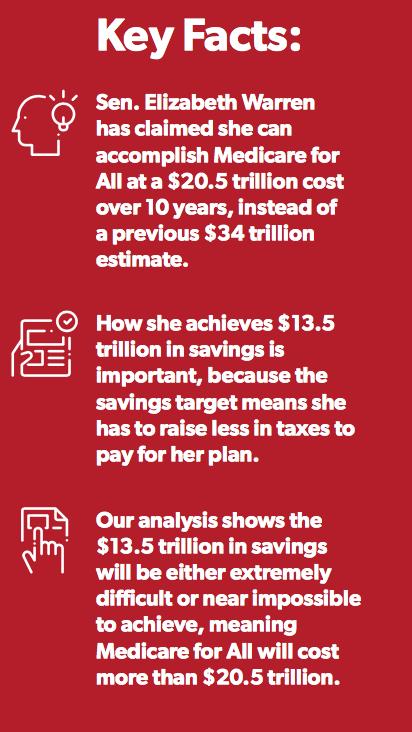

Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s Medicare for All plan released this month is the most detailed single-payer health care plan ever released by a major presidential candidate, and there have been major questions and concerns raised by health policy experts and economists. After all, a plan that (Warren claims) will cost $20.5 trillion over 10 years and fundamentally remake the American health care system is bound to receive scrutiny.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s Medicare for All plan released this month is the most detailed single-payer health care plan ever released by a major presidential candidate, and there have been major questions and concerns raised by health policy experts and economists. After all, a plan that (Warren claims) will cost $20.5 trillion over 10 years and fundamentally remake the American health care system is bound to receive scrutiny.

Warren’s suite of tax hikes, from a $9 trillion “Employer Medicare Contribution” to a financial transactions tax to “mark-to-market” taxation to an expanded wealth tax, would be extraordinarily disruptive and would dramatically increase the cost of capital, as pointed out by NTU Foundation’s Nicole Kaeding.

As disruptive and harmful as Warren’s proposed tax hikes are, though, they would be even worse if she were forced to reckon with what the Urban Institute has estimated is the real cost of a generous single-payer health care system in the U.S.: $34 trillion over 10 years. Here’s how the Urban Institute explained their estimate in an October 2019 paper:

“The enhanced single-payer approach eliminates all cost-sharing, offers broader benefits, and includes all US residents, including undocumented immigrants. Uninsurance is thereby eliminated, providing 32.2 million more people with insurance coverage than under current law in 2020. The additional federal spending for this reform is $34.0 trillion over 10 years, or $32.0 trillion after tax offsets.”

Instead, Warren’s team takes the $34-trillion estimate from the Urban Institute and outlines how she can find $13.5 trillion in savings over the first decade of MFA. To give a sense of the magnitude of these savings, that total is close to what the Congressional Budget Office projects the federal government will borrow from 2019 through 2029 ($13.0 trillion) and slightly above what the federal government will spend on the existing Medicare program from 2020 through 2029 ($11.6 trillion).

The $13.5-trillion total also represents nearly 40 percent of the Urban Institute’s cost estimate for Sanders-style MFA. Warren’s claimed 40 percent of savings deserve close consideration. Our analysis suggests that these claimed savings are questionable at best and near impossible to achieve at worst. If Warren refuses to address legitimate concerns and questions about her claimed savings, then her campaign owes voters additional financing options to achieve another $13.5 trillion in federal revenue. Otherwise this is a $13.5 trillion bet that taxpayers can’t afford.

Breaking Down the $13.5-Trillion Bet

Here’s a breakdown of the $13.5 trillion in dubious assumptions Warren makes about the cost savings she can achieve under MFA:

- $6.1 trillion in assumed maintenance-of-effort (MOE) payments from states

- $0.6 trillion from assuming hospitals will accept 110 percent of Medicare rates

- $1.8 trillion in unspecified “administrative savings,” without a defined plan for achieving those savings

- $1.7 trillion from cutting Medicare’s payments for brand-name drugs by 70 percent

- $2.3 trillion from Medicare payment reforms

- $1.1 trillion from slowing the growth rate of health spending over time

Below are more details on why the assumptions listed above will be extremely difficult to achieve at best.

State Maintenance-of-Effort (MOE) Payments

A near-majority of Warren’s assumed $13.5 trillion in savings (45 percent) come from payments that Warren would mandate state and local governments make to the federal government to finance the Medicare for All system.

The presumption is that the $6.1 trillion from states covers what they are currently projected to spend on Medicaid ($3.3 trillion), employee health coverage ($2.7 trillion), and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP; $17 billion) over the next decade. However, the plan claims states will be better off than current law because MFA slows the growth of health spending:

“This maintenance-of-effort is held constant as a consistent percentage of overall Medicare for All spending and grows with system cost growth, which we note above will be below current law projected growth. As a result, states will pay less over time than they would under current law.”

What Warren fails to note is that states retain significant control over their Medicaid and CHIP programs under current law, a fundamental trade-off of Medicaid’s federal-state cost-sharing structure. Warren is proposing that states give up all their control over program design and implementation, while owing the same amount of money on transfers to the federal government.

By ignoring any possibility that states will be unable to afford MFA’s MOE payments, Warren risks blowing a $6.1-trillion hole in her plan. Policymakers will face particularly acute pressure in states that are running deficits and/or have unfunded long-term liabilities. According to a 2018 report from the Mercatus Center, 15 states ran deficits in fiscal year (FY) 2016 and 11 states had unfunded pension liabilities exceeding 50 percent of personal income in FY 2016. And according to a Tax Foundation analysis, 21 states relied on federal aid for more than a third of their state general revenue in FY 2014. Even the least dependent state, North Dakota, relied on federal aid for 16.8 percent of its general revenue. It is dangerous to assume these states will gladly accept making annual, multibillion-dollar transfers to the federal government to run a single-payer health care system.

Warren’s Medium post on her plan claims states will “have far more predictable budgets, resulting in improved long-term planning for state and community priorities.” Her appendix on cost savings, though, notes that MOE payments are “held constant as a consistent percentage of overall Medicare for All spending and grows with system cost growth.” If MFA ends up costing more than Warren projects, then states will have to pay more, too - that’s hardly “more predictable” for state lawmakers and governors.

Warren may also experience state and local resistance to her required MOE payments. Medicaid expansion in the Affordable Care Act was pitched as a good deal for states - with the federal government picking up 90 percent of the tab - and yet 14 states have resisted the expansion to this day. Any state resisting MFA MOE payments would present financing challenges for a Warren administration, but states with large Medicaid budgets (California, New York, Texas, Pennsylvania, Florida, and Ohio, for example) would be the ones to watch from a financing perspective. Warren will also need to address resistance from states that take advantage of the current Medicaid system with a “provider tax” that effectively scams federal taxpayers. Here’s how Michael F. Cannon explained it in National Review:

“Medicaid’s matching-grant system also invites fraud. When a high-income state such as New York spends an additional dollar on its Medicaid program, it receives a matching dollar from the federal government — that is, from taxpayers in other states. Low-income states can receive as much as $3 for every additional dollar they devote to Medicaid, and without limit. If they’re clever, states can get this money without putting any of their own on the line. In a “provider tax” scam, a state passes a law to increase Medicaid payments to hospitals, which triggers matching money from the federal government. Yet in the very same law, the state increases taxes on hospitals. If the tax recoups the state’s original outlay, the state has obtained new federal Medicaid funds at no cost. If the tax recoups more than the original outlay, the state can use federal Medicaid dollars to pay for bridges to nowhere.”

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 43 states had hospital provider taxes in place in state fiscal year 2019, up from just 12 in 2004. While this scheme should certainly be addressed by federal policymakers, Warren’s plan takes the wrong approach in doing so.

Significant Cuts to Provider Rates

Of course, one central tenet of MFA is that all hospitals and doctors will now be paid by a single entity - the federal government - instead of a mix of public and private payers. One way Warren proposes to save money is to pay all hospitals 110 percent of current Medicare rates and all “physicians and non-hospital providers at 100 [percent] of current Medicare rates.”

Paying hospitals 110 percent of Medicare rates (instead of the 115 percent Urban Institute assumes in their estimate for Medicare for All) would save Warren $0.6 trillion over 10 years.

Some have suggested, though, that it is questionable to even assume hospitals will accept 115 percent of Medicare rates, as the Urban Institute does in its cost estimate for Medicare for All. That is why the Institute includes a “sensitivity analysis” for Medicare for All that assumes hospitals are paid at 140 percent of Medicare rates instead. That sensitivity adds another $2.9 trillion in 10-year costs, suggesting that Warren’s $13.5-trillion bet may actually be a $16.4-trillion bet.

For reference, consider what RAND Corporation says hospitals and physicians currently receive from commercial insurers:

“Commercial insurers pay 167 percent of the Medicare rate for hospital services and 125 percent of the Medicare rate for physician services (American Hospital Association, 2018; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2012).”

Warren assumes her system can convince hospitals to take a relative 34-percent cut on their current reimbursement rates from commercial insurers (from 167 percent to 110 percent of Medicare rates) and physicians to take a relative 20-percent cut on their current reimbursement rates from commercial insurers (from 125 percent to 100 percent). Even when accounting for unspecified administrative savings, reimbursement for care that is currently uncompensated, and higher rates for Medicaid patients, it’s hard to imagine steep MFA provider cuts going over smoothly with hospitals and doctors. Even a 16-percent cut for hospitals, from 167 percent of Medicare rates to 140 percent of Medicare rates in one Urban Institute model, would be politically difficult to achieve.

For some historical context on the difficulty of achieving provider cuts in Medicare, consider the long and tortured “doc fix” debate that raged in Congress for more than 12 years. As the Congressional Research Service (CRS) explained:

“Established as part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-33), the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) is the statutory method for determining the annual updates to the Medicare physician fee schedule (MPFS). In essence, if actual expenditures are within a “sustainable” expenditure target, payment updates are calculated according to a predetermined formula. If, however, the actual experience exceeds the sustainable target, future updates are reduced to bring spending back in line with the target over time.

...Beginning in 2002, the actual expenditure exceeded allowed targets, and the discrepancy has grown with each year. However, with the exception of 2002, when a 4.8% decrease was applied, Congress has enacted a series of laws to override the reductions.”

The repeated rate freezes or increases built the problem up to such an extent that doctors were facing “a 21% reduction in payment rates” under the Medicare physician fee schedule (MPFS) in April 2015. Instead, Congress permanently repealed the SGR formula.

In a world where MFA passes under a Warren administration, it is easy to imagine immense pressure from hospitals and doctors leading to a “doc fix” redux, where stakeholders convince Congress to freeze or delay rate reductions again and again. This would add to the costs of MFA and eat significantly into Warren’s projected savings.

“Administrative Savings”

Warren’s appendix on cost savings goes into some detail on the difference in administrative costs between the private health sector and Medicare. The summary? “In 2017, private insurers spent 12.2% of total premiums collected on administrative costs. According to the Medicare Trustees Report, the administrative costs of traditional Medicare (Parts A and B) are 2.3%.”

Warren claims that “setting the administrative spending of Medicare for All to 2.3% would decrease NHE and federal spending by $1.8 trillion over ten years.” She does not outline a way to achieve these administrative savings, all while the federal government creates, develops, and administers a single-payer health care system for more than 300 million Americans. The RAND Corporation had a more modest estimate of administrative savings from MFA, about 5.6 percent of costs (or more than double Warren’s goal). And if Warren is to use government resources to assist the hundreds of thousands of Americans who could lose their jobs under a single-payer system, she will need to find a way to pay for that as well.

For now, Warren’s $1.8 trillion in administrative savings should be considered a vague and difficult-to-achieve goal, not a real proposal that makes her version of MFA cost less than the Urban Institute estimate.

The Rest

Beyond what has already been examined, Warren’s plan includes:

Steep cuts to what the federal government will pay for prescription drugs ($1.7 trillion in savings): Warren appears to borrow many elements from the onerous H.R. 3 legislation introduced by Speaker Nancy Pelosi, but features an aggressive goal to cut what Medicare reimburses for brand-name prescription drugs by a shocking 70 percent. NTU wrote in September that H.R. 3 “combines all the worst elements of government-first approaches to prescription drugs, including foreign price controls, inflation caps, and federally-mandated price negotiations.” We have every reason to believe Warren’s plan would have an even worse impact on new treatments and cures than H.R. 3, which according to the Congressional Budget Office would result in the development of eight to 15 fewer new drugs over the next ten years.

Promising but challenging Medicare payment reforms ($2.3 trillion): This is perhaps the one element of Warren’s cost savings plan that holds some promise, because it incorporates some bipartisan ideas to reform how Medicare pays for items and services: site neutral payments ($0.5 trillion in savings), post-acute payment reform ($0.5 trillion), and bundled payments ($1.2 trillion in savings). Two notes of caution, though. First, the appendix warns that “the site neutral and post-acute payment reforms are pure extrapolations of the CBO analysis, [and] we further adjusted the bundled payment extrapolation to reflect the desired policy outcome of reducing this spending.” Second, Vox wrote in its analysis of the Warren plan that “[a] 2018 Commonwealth study found no savings from bundled payments, and Medicare has been backing off the program in recent years.”

The assumption that the growth of health spending will slow over time ($1.1 trillion): This part of the analysis assumes Warren’s plan can slow the growth rate of health spending by 29 percent, from the 5.5-percent cost growth estimated by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to a 3.9-percent goal. Much like the promised administrative savings outlined above, this is more a desired outcome than a plan for getting there.

These additional elements deserve further scrutiny. What is clear, though, is that beyond the onerous tax hikes Warren proposes to pay for $20.5 trillion in MFA spending - through the first decade alone - the plan will likely cost much more than she is currently estimating. The $13.5 trillion in savings she proposes, compared to the Urban Institute’s $34-trillion estimate for MFA, will be extraordinarily difficult to achieve at best and near impossible at worst.

Conclusion

At a minimum, voters deserve additional financing options from Warren to cover the possibility that she cannot achieve these significant savings. Even better would be for Warren and Sanders to drop their astronomically expensive single-payer proposals. Instead, they should work with policymakers on bipartisan proposals that expand health coverage, lower costs, and make health care a more robust, competitive, and market-based industry that serves patients, consumers, and taxpayers.