As the NFL preseason starts up in earnest, fans are getting their first glimpses of professional athletes in their new uniforms on national television — including recently-relocated free agents who signed contracts with eye-popping dollar figures just months prior. While the preseason narratives will focus on the competitive implications of free agent destinations, the financial ones play just as big of a role.

Rarely do consumers of any entertainment product take as keen an interest in the dollars and cents behind the operation as sports fans do while tracking free agent contracts. But while the gross salary offered tends to get the most attention, the amount of take-home pay an athlete can look forward to depends a great deal on what state gets to tax that salary. And while taxes always matter to taxpayers, in the context of NFL megadeals, an extra percentage point of tax here or there can be the difference between millions of dollars in additional tax liability.

That state tax obligation entails a caveat: athletes, while able to benefit from lower state income taxes in their state of residence, must pay taxes to other states when they play games in those states. This obligation, known as the “jock tax,” may at first glance seem to suggest that the advantages of signing a contract with a more tax-competitive state is overstated. But, in reality, the main impact of the jock tax is to significantly complicate athletes’ tax returns, all while shifting around tax dollars in a kind of state-level shell game that has a minimal overall impact on state revenues.

Contrary to what one might think, the jock tax generally does not have much of an impact on an athlete’s overall tax liability (and even less impact on state budgets), making the associated compliance burdens on players and team staff hardly a worthwhile tradeoff.

Background: “Michael Jordan’s Revenge”

The first jock tax came, appropriately, from a good, old-fashioned petty sports rivalry. After Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls beat the Los Angeles Lakers in the 1991 NBA Finals, California got back at Jordan in a very California way: applying its income tax to Jordan and his fellow Bulls on income earned during days spent in California. Illinois quickly retaliated by levying a jock tax against players from any state that imposed a jock tax on Illinois athletes, a reaction dubbed “Michael Jordan’s Revenge.”

But what started as a tax slap-fight between two states quickly spread, as legislators elsewhere recognized an opportunity to pull in extra revenue from a group of individuals who were unable to retaliate at the voting booth and generally unsympathetic: nonresident, wealthy athletes. Today, the only states that do not levy jock taxes are those with no state income tax.

While jock taxes have succeeded in becoming ubiquitous, they have not had the desired effect of pumping states’ coffers full of taxes from rival teams’ players. A March 2020 analysis calculated the potential revenue implications for states of lost jock tax revenue from canceling remaining NBA, NFL, and MLB games in 2020 — including the end of the NBA regular season and the entire 2020 NFL and MLB seasons (excluding playoffs). Across 20 states (and D.C.) with professional sports teams in these three leagues and an individual income tax, this study estimated that lost jock tax revenue would amount to about $295 million.[1]

In the context of state budgets, that is a drop in the bucket — representing about 0.1 percent of individual income tax collections alone in those states and D.C (and about 0.02 percent of total revenues). What’s more, even this is actually a substantial overestimate, as it does not account for the fact that states imposing jock taxes must also provide tax credits to their own resident athletes for jock taxes they paid to other states. Consequently, jock taxes largely cancel each other out except when athletes from states with no income taxes are involved.

Aside from the fact that jock taxes function as little more than a revenue shell game, the way that jock taxes are actually applied is not conducive to massive revenue differences. States calculate jock taxes based on a percentage of “duty days” spent in that state. “Duty days” include not just game days, but essentially the entire NFL calendar, including training camp and practices. In the NFL, for example, a road team playing a game in a state usually is in and out within two or three days, meaning that that state can only claim about 1 or 2 percent of that player’s total “duty days” and income taxes.

States that have tried to make nonresident athletes more of a lucrative revenue source have largely been forced into line over the years. Cleveland’s attempt to claim visiting players’ income taxes as a percentage of games played rather than duty days when applying its local income tax, a formula which enabled it to claim far more of a visiting athlete’s income than the duty days method, was struck down by the Ohio Supreme Court in 2015 after a Chicago Bears linebacker noticed a disproportionate amount of his paycheck was going to Cleveland.

Pittsburgh made its effort to juice up its jock tax even more brazen. While the city applied a 1 percent income surtax to resident athletes, it tried to apply the same tax at a 3 percent rate to visiting athletes. The tax was struck down as unconstitutional by the Alleghany County Common Pleas Court, a decision which was recently upheld by the Commonwealth Court. While Pittsburgh recently appealed the ruling to the state Supreme Court, the facts are not on the city’s side.

Compliance Burdens

But while states and localities do battle with jock taxes, the “jocks” themselves are the ones most impacted. While most taxpayers expect to file tax returns in one or two states, athletes must file returns in each state that they play in with an individual income tax — generally around 15 or 20. Not only does this take significantly more time than filing in one state, most tax preparation services charge extra for each additional state return that must be filed.

And while this study will focus primarily on the implications of the jock tax on some of the most highly-paid free agents for illustrative purposes, it is worth remembering that many athletes subjected to the jock tax are not nearly as highly-compensated. Athletes subjected to the “jock tax” include not just those with annual salaries in the seven-or-eight digit range, but also athletes who are far more modestly compensated — for instance, WNBA rookies Caitlin Clark and Angel Reese earn rookie salaries of around $75,000, while the minimum salary for MLS players is even lower. Minor league salaries can be lower than $20,000. All of these athletes face the same obligations to file tax returns in states all around the country as the highest-profile (and highest-paid) athletes in the country.

These obligations also extend to members of a sports team’s staff, such as coaches, trainers, assistants, and so on, most of whom earn salaries in line with the average taxpayer. These nonresidents are an easy target since they cannot voice their displeasure at the ballot box, but the lack of political consequences does not justify the substantial compliance burdens heaped on them for relatively paltry amounts of revenue.

Case Study: Kirk Cousins

The biggest free agent deal so far this NFL free agency involved former Minnesota Vikings quarterback Kirk Cousins, who signed with the Atlanta Falcons. Cousins received a four year, $180 million contract with a $50 million signing bonus. According to Overthecap, Cousins is due to receive $12.5 million in base salary this coming year, meaning that he will earn $62.5 million in 2024.

While Georgia still has an income tax, there are clear tax advantages to his choice of Atlanta over returning to Minnesota. Georgia assesses a flat income tax rate of 5.49 percent, whereas Minnesota’s top rate is 9.85 percent. For someone set to earn $62.5 million, the top tax bracket is almost the only one that matters.

We do not have access to Cousins’s actual (and likely far more complicated) tax return, so we work with the simpler assumptions that he files jointly with his wife and claims the standard deduction as well as two child dependents where applicable. Before factoring in the jock tax, the tax benefit of Cousins’s move to Atlanta is clear. Cousins’s estimated $6.1 million Minnesota state income tax instead becomes a $3.4 million Georgia tax bill.

The jock tax comes nowhere near to making up as much of that gap as states may hope. Assuming that visiting players incur 3 “duty days” in that state per game (teams often fly in on Saturday and depart Sunday for a Sunday afternoon game, but we add the extra day to account for primetime games and more lax travel schedules), the NFL has 166 duty days, meaning that a state can usually tax about 1.81 percent of a visiting player’s income.

In 2024, the Atlanta Falcons are set to play 9 games in Atlanta and 8 games on the road. Two of those road games, against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Las Vegas Raiders, are played in states with no income tax, but Cousins will still have to pay Georgia income taxes for those games. In cases where Cousins plays a game in a state with a higher income tax, he can claim a credit against his Georgia taxes up to the level of tax that he would have paid if the income was allocable to Georgia.

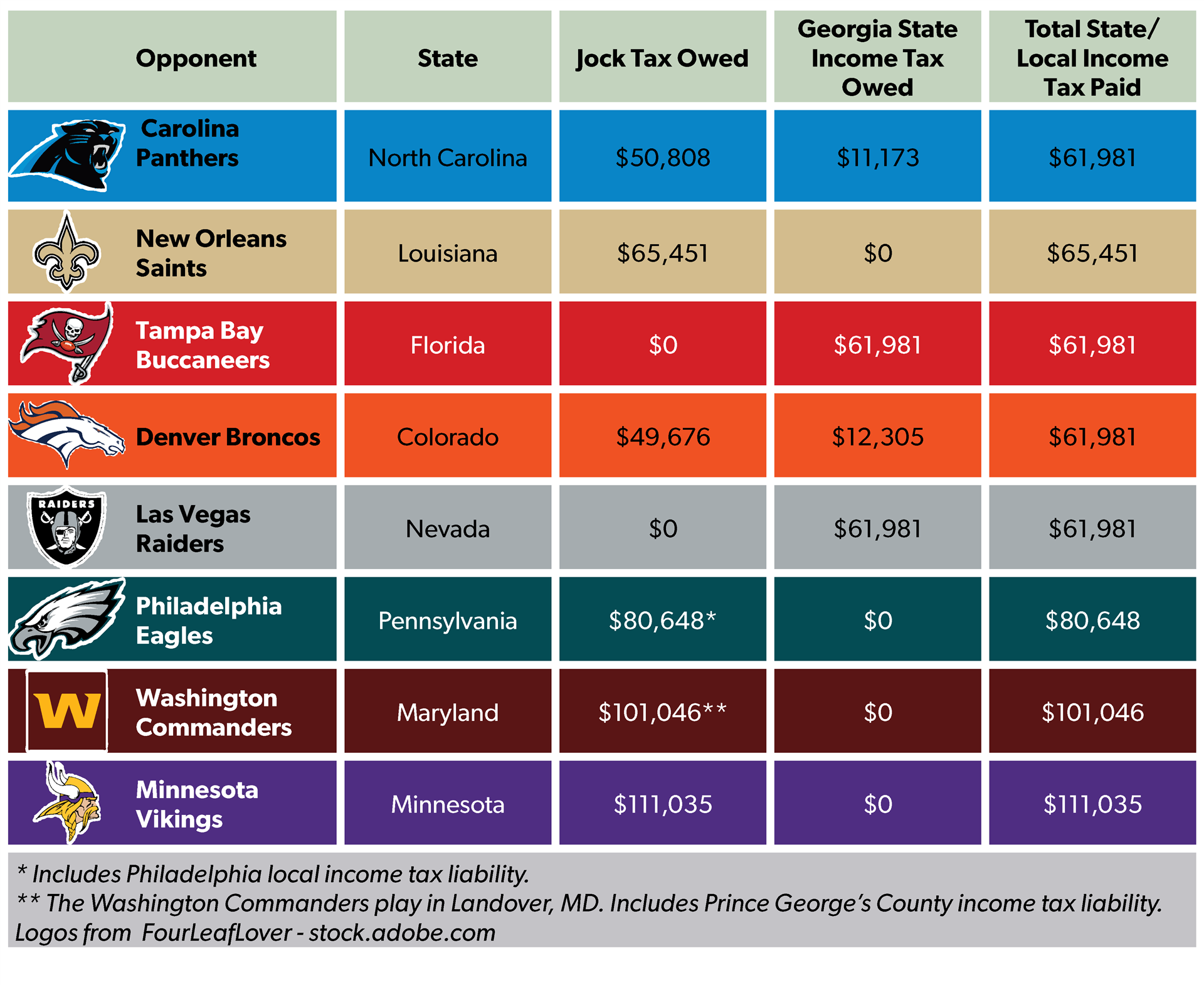

The following table calculates the state (and local) income tax Cousins owes to each state per road game on his $62.5 million 2024 salary.

In total, Cousins is estimated to have a state income tax liability of $3.6 million for this year playing for the Falcons. Had he opted to stay in Minnesota and received the same contract offer, Cousins would have owed $6.2 million in state income taxes. Jock tax obligations do little to narrow the gap. Compared to his income tax liability in the absence of the jock tax, Cousins is estimated to owe just $172,000 more in tax, or just over 5 percent more than he otherwise would have paid. In other words, jock tax obligations represent only about 6 percent of the difference between Cousins’s tax bill playing for the Falcons versus his tax bill playing for the Vikings.

Only $520,000 of Cousins’s $3.6 million total tax bill playing for the Falcons, or less than 15 percent, is owed to states other than Georgia. Those other states also must also credit their own resident athletes for jock taxes paid to other states, making this already mediocre windfall even more paltry. Cousins ends up paying a fraction of a percentage point of his overall 2024 salary to other states.

Cousins would have also had to pay jock taxes had he opted to stay in Minnesota under the same contract, but a similarly small amount. Only two road games, against the Los Angeles Rams and the (New Jersey-based) New York Giants, would have resulted in a higher state income tax burden than Minnesota’s high income tax rates. From these two games, Cousins would have been liable for an additional $48,000 in income taxes for a total of $6.2 million in state income taxes — about 0.8 percent more than if he only owed taxes to Minnesota.

Case Study: Baker Mayfield

But what about players who reside in states that do not already tax income? To see how jock taxes impact these players, we can look at another quarterback in the same division who signed this free agency period, or rather re-signed, with the Florida-based Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

Mayfield received a three-year, $100 million contract, with a $28.875 million signing bonus. His low year one base salary means he will earn exactly $30 million in income from the Buccaneers in 2024, according to Overthecap. Once again, we will assume that Mayfield takes the standard deduction, files jointly with his wife, and will claim his soon-to-be-due [10] first child as a dependent.

Since Florida has no state income tax, road games are more impactful for Mayfield’s tax bill than Cousins’s. Every state he owes income tax to for road games represents a flat increase to his overall state tax bill, since he has no opportunity to credit those taxes paid against the non-existent Florida income tax.

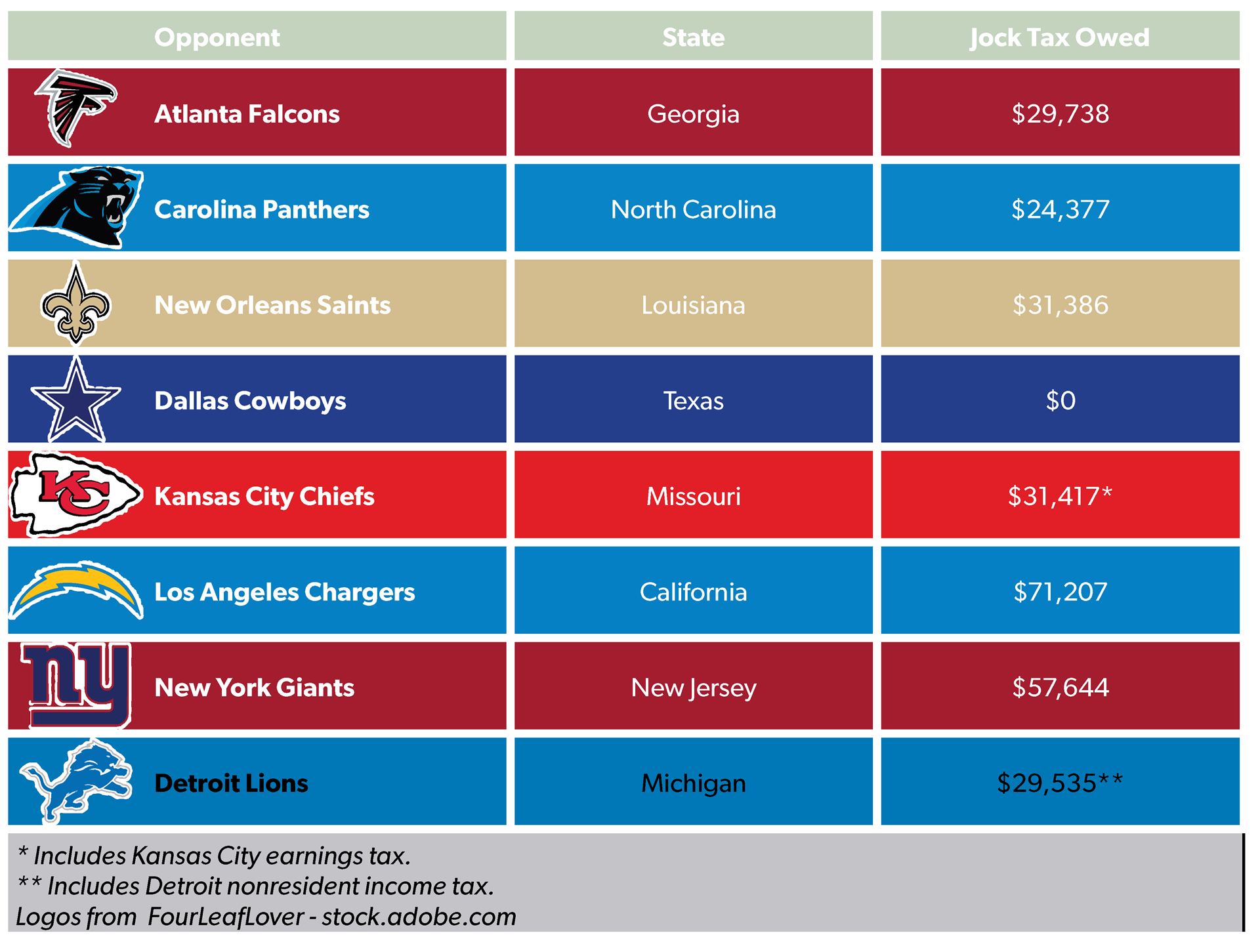

Using the same assumptions about duty days as Cousins, below is Mayfield’s estimated state and income tax bill for each of the eight road games he is scheduled to play in 2024.

While Mayfield’s effective jock tax rate ends up being about three times higher than Cousins’s, it certainly does not come close to erasing the tax advantage of playing in a state with no income tax. Mayfield ends up owing an estimated $275,000 state income tax bill to other states while playing for the Buccaneers — far preferable to the roughly $3 million he would have owed had he chosen to sign the same contract in Minnesota.

Policy Implications

While Cousins and Mayfield likely did not choose the Falcons and Buccaneers entirely because of state income taxes, the free agency decisions that each quarterback made left them better off from a tax perspective. Choosing low-tax or no-tax states reduced their tax bills by over $2 million in each case, and state efforts to recapture some of that through jock taxes fall far short of doing so.

The relatively minimal impact on overall state revenues should call into question the justifications for imposing jock tax obligations on visiting athletes. In this case, principles of good tax policy take a backseat to the opportunity to tax nonresident millionaires. But with the revenue impact proving minimal for states, the fairness of the jock tax deserves greater attention.

A key consideration in determining which jurisdiction has the power to tax certain income is the “benefit principle,” or the idea that tax obligations should be connected to the benefits received by the taxpayer. This connection is rarely as direct in public finance as it is in a private transaction, where a customer pays for a specific good or service — for instance, tax dollars fund services and programs that an individual taxpayer may never benefit from, and wealthier taxpayers generally are obligated to pay more in taxes for the same government services.

Nevertheless, while the pay-in is not necessarily equivalent to the payout, taxpayers’ tax dollars should generally go to the jurisdiction in which the taxpayer benefits from government services. A taxpayer with a house in Maine should not pay property taxes on that house to California.

Jock taxes are not a good example of this principle in action, however. A sports stadium and the local services necessary to operate and maintain it are what enable the home team to function and earn income, not the away team. Just about every road team would be perfectly happy to host every single game themselves — from a competitive standpoint, but even more so from a financial one.

More to the point, nexus in a highly interconnected economy must be balanced by common sense. When the meager revenues to be collected are so thoroughly outweighed by the additional compliance burdens created for taxpayers as with the jock tax, states should consider replacing rigid, abstract rules with ones that incorporate reasonable safe harbors protecting taxpayers from frivolous obligations.

After all, the proliferation of justifications that states are using to claim the power to tax nonresident taxpayers has only harmed taxpayers. While the fiscal impact has been to shuffle tax revenue between states with little overall impact on revenues, average taxpayers and tax paying businesses that once could count on having to file one, maybe two, state tax returns increasingly find themselves obligated to file in states around the country based on the most tangential connections to those states.

State tax administrators personally unaffected by these rules may see obligations as justified by even the smallest revenue increases. But legislators should recognize that additional tax returns have a cost to taxpayers as well, as an additional tax return means one more state’s tax code that a taxpayer must take the time to understand, comply with, and even potentially face an audit from.

As state tax filing burdens continue to accumulate for taxpayers, state legislators will increasingly need to grapple with this reality. Filing and paying taxes is complicated and stressful enough without states burying taxpayers under piles of unnecessary paperwork for the sake of trying to squeeze taxpayers for every possible dollar that can be attributed to their state.

Conclusion

As these examples show, jock taxes are primarily notable for how ubiquitous they have become as pillars of state tax policy despite the minimal revenues they generate. Certainly, they are a long way from making up ground between high-tax states and low-tax states for athletes.

States that currently enforce these taxes should consider whether or not the burden on taxpayers and interstate commerce is truly worthwhile. Should states prove unwilling to “unilaterally disarm,” Congress may have a role to play in clarifying what states have the power to tax what income — after all, the status quo is a clear burden on interstate commerce as states create compliance burdens for traveling athletes and staffers that end up doing little to actually increase revenue in those state

More broadly speaking, state legislators must begin to consider the implications of unrestrained claims of nexus not only on their budgets, but also on the taxpayers facing these assessments. Taxpayers should not be stuck as the rope in an ever-expanding tax tug-of-war between states.

[1] The study actually estimates $307 million, but it incorrectly assigns approximately $12-14 million in jock tax revenue to Nevada and Washington, states with no individual income or jock taxes.