Read more from our experts on the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

Key Facts:

- The One Big Beautiful Bill Act makes permanent some of the most important individual and business income tax provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, implements tax reforms promised by President Trump on the campaign trail, and reduces spending on Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

- The bill is expected to increase gross domestic product (GDP) by 1.2 percent in the long run largely due to permanent business tax reforms such as full expensing.

- The bill is expected to decrease revenue by $4.45 trillion over ten years and reduce spending by $1.1 trillion over ten years.

Just before July 4, Congress enacted and President Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) into law.

OBBBA addresses a critical issue for taxpayers by making permanent several individual income tax cuts from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 that were due to expire at the end of this year. Without OBBBA, 62% of Americans would have seen a combined tax increase of $3.3 trillion at the end of the year.

OBBBA also makes permanent TCJA’s full expensing for business equipment, a pro-growth policy that will encourage investment and job creation. In addition, OBBBA permanently restores or broadens some business tax provisions that were terminated or tightened by the TCJA, such as immediate expensing of research and development costs and business interest deductions. Finally, it makes permanent business tax provisions created by the TCJA, including international tax provisions and opportunity zones.

To reduce the overall cost of the bill, OBBBA implements spending reforms for Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and eliminates or phases out several industry-specific green energy tax credits enacted in recent years. Medicaid and SNAP reforms change eligibility requirements, implement safeguards against fraud and abuse, and increase cost-sharing with states. Green energy tax credits that were created or enhanced by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are phased down or phased out by OBBBA. Many of these cost-saving measures take effect later in the budget window.

All told, the bill will reduce revenue by $4.45 trillion and reduce spending by $1.1 trillion over ten years.

As my National Taxpayers Union colleague Brandon Arnold said right before the bill passed:

Individual Taxes

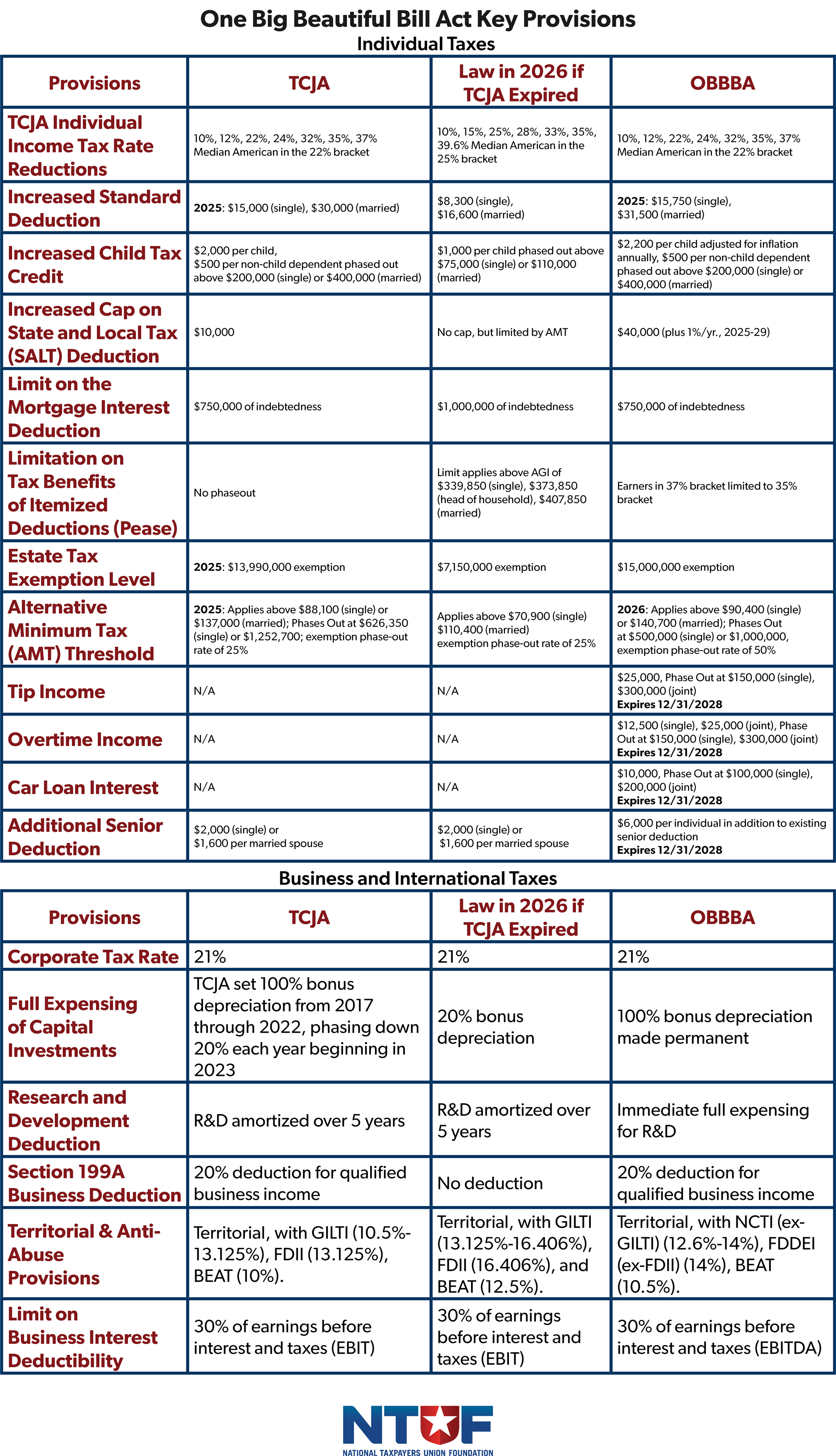

- Individual income tax rate cuts from TCJA are made permanent by OBBBA. Individual income tax rates fall into seven brackets at 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37% compared to pre-TCJA rates of 10%, 15%, 25%, 28%, 33%, 35%, and 39.6%. Individual income tax rates for nearly every tax bracket were scheduled to revert to their previous higher levels beginning in 2026, which would have reduced taxpayers’ disposable income by more than $2 trillion over ten years.

- The standard deduction, which was doubled by TCJA and set at $15,000 for single filers and $30,000 for married filers in 2025, is made permanent by OBBBA and increased to $15,750 for single filers and $31,500 for married filers for 2025. Nearly 90% of taxpayers claim the standard deduction now compared to about 70% of taxpayers prior to TCJA becoming law. This shift dramatically simplifies filing: our estimate shows that it saves Americans 210 million hours a year in compliance time worth nearly $13 billion.

- The Child Tax Credit (CTC), doubled to $2,000 per child by TCJA, is increased to $2,200 per child and adjusted for inflation permanently by OBBBA. The CTC is available to an estimated 90% of families with children and is a key factor in reducing the effective tax rate for families at lower income levels. Without this provision, the CTC would have been cut in half from $2,000 per child to $1,000 per child in 2026. OBBBA’s CTC extension and increase will reduce the tax liability for families by $816 billion over ten years compared to if TCJA had expired, with nearly one quarter of that in the form of cash transfers to families at the lowest income levels.

- The Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) exemption changes made by TCJA were made permanent by OBBBA with some adjustments. The TCJA AMT threshold was made permanent, including the annual inflation adjustment. The earnings level at which the AMT exemption phases out was reverted to TCJA’s 2018 level of $500,000 for single filers and $1,000,000 for married filers, slightly less than the 2025 level of $626,350 for single filers or $1,252,700 for married filers. The phaseout rate was also increased from 25% to 50%.

- Prior to TCJA, about 5 million taxpayers were subject to the AMT, requiring them to calculate their AMT liability separately from the rest of the tax code without having certainty as to whether the AMT would even apply to them after having completed the calculations. While many taxpayers subject to the AMT are in the upper-middle income range, TCJA effectively ensured that households earning under $200,000 are not subject to the AMT at all. It also removed the AMT liability for nearly all households earning less than $500,000, compared to roughly 20% who were subject to it before TCJA passed. The higher amount of income exempt from AMT calculation and other changes from TCJA were scheduled to expire in 2026.

- The state and local tax (SALT) deduction cap is increased from TCJA’s $10,000 level to $40,000 for 2025 and further increases by 1% each year until 2029 at which point the cap will revert to $10,000 permanently. The SALT deduction cap begins to phase out for earners with $500,000 or more in 2025 with the phaseout threshold increasing by 1% each year after. The SALT cap phaseout has a floor of $10,000, allowing for a minimum deduction for the highest earners, and expires after 2029. TCJA’s SALT cap for 2025 is $10,000 and was scheduled to expire in 2026, however OBBBA applies the higher $40,000 cap to 2025.

- Raising the SALT cap overwhelmingly benefits high-income taxpayers in high-tax blue states. In fact, nearly 80% of the benefit of raising the cap to $25,000, far below OBBBA’s cap, would have gone to blue states. Under a $40,000 cap, the bottom 80% of taxpayers see no benefit from the increased cap. The highest-income earners who were most affected by TCJA’s $10,000 SALT cap effectively already faced a SALT cap due to Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) liability, which TCJA eliminated for millions of taxpayers. Therefore, these taxpayers exchanged the much more complex AMT for a much simpler reform. These taxpayers also benefited significantly from TCJA’s reduced top income tax rate. Retroactively increasing the cap is estimated to cost $5 billion in 2025. In 2026, the higher SALT cap is expected to raise only $31.6 billion compared to $106.7 billion in revenue in 2030 when the higher cap expires.

- The pass-through deduction for small businesses of 20% enacted by TCJA is made permanent by OBBBA. Roughly 90% of small businesses file taxes through the individual income tax code and are therefore subject to individual income tax rates rather than the corporate income tax rate. When lawmakers reduced the tax burden for corporations through TCJA, they also reduced the burden for these small businesses by introducing a 20% deduction for pass-through income, or Section 199A deduction, that was due to expire at the end of 2025. While some versions of OBBBA included expansions to the pass-through deduction, the final version simply made the current 20% deduction permanent.

- Opportunity zone tax incentives introduced by the TCJA are made permanent by OBBBA. States can designate certain low-income census tracts as “opportunity zones” allowing investors to receive special capital gains tax treatment for their investments in those areas. Investors can defer their capital gains tax liability while they hold the investment with the condition that those gains are invested in a qualified opportunity fund (QOF) within 180 days. OBBBA also made permanent a 10% step-up in basis for gains held in a QOF for five years and a waiver of tax liability for gains incurred after investment in the QOF is held for ten years, but allows for gains to be incurred after 30 years. The opportunity zone program has been in place since 2018 and was due to expire at the end of 2026. The benefits of opportunity zones are still unclear. Research indicates that much of the investment in opportunity zones would have occurred regardless of the tax benefit, a conclusion also made by the Government Accountability Office (GAO). GAO and Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) have separately raised awareness of lack of transparency for the program due to insufficient data collection. Importantly, OBBBA adds new reporting requirements and penalties for non-compliance. These changes take place beginning in 2027.

- Tip and overtime earnings are now deductible under OBBBA subject to limits until the end of 2028. Tip income up to $25,000 and overtime income up to $12,500 can be deducted above-the-line with both deductions phasing out for single filers earning $150,000 or married filers earning $300,000.

- Car loan interest payments are now deductible under OBBBA up to $10,000 until the end of 2028. This deduction begins to phase out for single filers earning $100,000 annually or married filers earning $200,000 annually.

- An additional deduction for seniors was added by OBBBA to fulfil President Trump’s “no tax on Social Security” campaign promise while abiding by Senate budget reconciliation rules. This allows an above-the-line deduction of $6,000 per individual for seniors over 65 who are U.S. citizens. This deduction phases out This deduction begins to phase out for single taxpayers with modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) over $75,000 or $150,000 for married taxpayers.

Business Taxes

- Full expensing, or 100% bonus depreciation, is made permanent by OBBBA. TCJA enacted full expensing on a temporary basis at 100% from 2017 through 2022, phasing down by 20% annually and completely expiring by 2027. For 2025, bonus depreciation is 40%. Full expensing alone accounts for nearly half of the economic growth impact of OBBBA according to the Tax Foundation. This is remarkable considering full expensing is a tax shift rather than a tax cut. While full expensing reduces government revenues in the short-term, it allows businesses to deduct the full cost of certain investments in the year the cost is incurred rather than deducting the cost over many years. OBBBA also temporarily allows full expensing for qualified production structures until the end of 2028.

- Immediate research and development (R&D) expensing is reinstated and made permanent by OBBBA. In an effort to make the budget math work, the TCJA disallowed immediate deduction of R&D costs, requiring that companies capitalize or amortize the cost of their R&D expenses over five years. OBBBA reverses this, bringing R&D treatment back to its historical norm, and allows limited retroactive R&D expensing to 2022 for certain small businesses. This commonsense tax treatment has been championed on both sides of the aisle and will contribute more to economic growth than estimates suggest due to spillover effects over time.

- International tax reforms from TCJA were made permanent and changed by OBBBA. Specifically, the bill keeps TCJA’s three signature international taxes but at higher rates. The Global Intangible Low-Income tax (GILTI) created by TCJA was renamed to the Net Controlled-Foreign Corporation Tested Income (NCTI) tax and its tax rate was increased along with the rates for the Foreign Direct Investment Income (FDII), now the Foreign Derived Deduction Eligible Income (FDDEI) and the Base-Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT). The tax rates are now 12.6% to 14% for NCTI, 14% for FDDEI, and 10.5% for BEAT. This compares to TCJA’s rates of 10.5% to 13.125% for GILTI, 13.125% for FDII, and 10% for BEAT. NCTI, formerly GILTI, is now calculated using a 40% deduction rather than TCJA’s 50% deduction and FDDEI is now calculated using a 33.34% deduction rather than TCJA’s 37.5% deduction. The name change for NCTI reflects that this tax is now calculated using more than just intangible sources of income due to removal of the Qualified Business Asset Income (QBAI) exclusion that reflects tangible property. TCJA restructured U.S. taxation of multinational firms through these tax mechanisms, which alongside a lower corporate income tax rate, entirely stopped a growing pre-TCJA trend of corporations moving their headquarters overseas for tax purposes.

Spending Changes

- Health care reforms enacted by OBBBA will implement guardrails against enrollees’ income misrepresentation which results in improper payments of Advanced Premium Tax Credits (APTC) of $10 billion annually. It also introduces work requirements for certain Medicaid enrollees beginning in 2027, with exceptions for Native Americans, veterans, and others. It also limits the program to U.S. citizens, ends the practice of automatic re-enrollment, and requires enrollees to verify their eligibility more frequently. OBBBA also requires certain Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) beneficiaries to work 80 hours per month and shifts some administrative costs to the states.

- Green energy tax credits are eliminated or phased out by OBBBA. New green energy tax credits enacted by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022 have ballooned in estimated costs. The electric vehicle tax credit was initially estimated to cost around $14 billion over ten years, later increased to $70 billion, and experts now estimate the true cost would be around $390 billion over ten years. Left unchecked, the total cost of the IRA’s green energy tax credits could reach over $1 trillion, significantly higher than the original estimated cost of around $271 billion. OBBBA reforms these by phasing out production and investment tax credits for wind and solar energy and eliminating electric vehicle tax subsidies. It also terminates other tax credits created by the IRS including those for clean hydrogen, sustainable aviation fuel, advanced manufacturing, and zero-emissions facilities. This will save $500 billion over the ten year window.

Additional Items

- Excise taxes on remittances of 3.5% is a new policy.

- Excise taxes on investment income of private colleges and universities up to 8% is an expansion of existing policy, raising the tax rate from 1.4%.

- Taxing the excess compensation of non-profit executives is an expansion of current law.

- 529 education account changes are a modification of current law.

- Tax credits for employers providing paid family or medical leave are an extension of TCJA policy.

- Tax credits for employers providing child care are a modification of current law.

- Tax credits for adoption are a modification of current law.

Other TCJA Extensions

- Changes to ABLE accounts are an extension and modification of TCJA policy.

- Limitation on deduction for qualified residence interest is an extension of TCJA policy.

- Modifying the treatment of gambling losses is a modified extension of TCJA policy.

- Tax treatment of qualified transportation and fringe benefits is an extension of TCJA policy.

- Deduction limits and exclusions for moving expenses is an extension of TCJA policy.

- Excluding student loans from gross income on account of death or disability is an extension of TCJA policy.

Other Changes to Current Law

- Exclusions for Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) gain are a modification of current law.

- Repeal of 1099-K reporting threshold terminates Inflation Reduction Act policy that failed to fully come into effect.

- Raises the 1099-NEC and 1099-MISC thresholds for reporting nonemployee compensation and other payments from $600 to $2,000, easing compliance for small businesses.

Analysis

According to Congress’s official tax scorekeeper, the majority of the tax cuts in OBBBA are directed toward individuals, families, and middle-class workers. Tax changes for middle-class taxpayers, most of which extend TCJA policy, and President Trump’s campaign promises account for roughly $4.13 trillion in tax cuts over ten years. In fact, whether you view the tax cuts relative to current law or current policy, tax cuts geared towards individuals account for the majority of the bill, amounting to $778 billion on a current policy basis.

Analysis from the Tax Foundation confirms that middle-income taxpayers will see the largest increase in after-tax income—more than 5% in 2026—from OBBBA’s individual income tax cuts. The Tax Foundation also finds that taxpayers who may initially see a tax increase due to more stringent eligibility requirements for certain credits will see a 0.5% increase in after-tax income later in the budget window when accounting for economic growth effects.

While many of these provisions are broad-based, some of the TCJA reforms made permanent benefit only a niche group of taxpayers. Raising the state and local tax (SALT) deduction cap, for example, is a highly regressive move that benefits the wealthiest taxpayers in high-tax states. It also unnecessarily trims back an important revenue-raising provision of the TCJA.

Alongside making permanent the signature individual income tax cuts from the TCJA, OBBBA also included many new tax cuts promised by President Trump on the campaign trail. These include tax cuts for tipped workers, workers earning overtime, and taxpayers paying interest on auto loans, as well as an additional deduction for seniors—all of which expire at the end of 2028.

While permanent tax policy is best for taxpayers, giving these provisions an expiration date is a reasonable approach. Some of these policies may be burdensome for the government to administer and for taxpayers to navigate. Implementing them for a trial period provides time to gather feedback on their overall effect, allowing an opportunity for reforms in the future if needed.

NTU’s Brandon Arnold suggests an alternative policy to provide tax relief to tip-workers and those working overtime. Congress could create a “Trump Tips and Overtime Deduction” which would be a broad-based and simple deduction of $1,000 available to all workers and would not require taxpayers to spend hours collecting receipts and paystubs to prove that they qualify.

In addition, the car loan interest deduction can be enhanced through adding guardrails. The deduction is not available to all car buyers; it only applies to buyers taking out a loan and purchasing a new car, and the new car must be assembled in the United States. This incentivizes taxpayers to purchase a vehicle out of their price range that may not suit their preferences. For example, taxpayers may be better off with a used foreign-manufactured car, which are often the most reliable used cars on the market. A better way to structure the car loan interest deduction would have been to include a limit on the loan term and monthly payment to discourage unsustainable household indebtedness.

On the business side, OBBBA makes permanent some of the most pro-growth elements of the 2017 tax reform, brings back tax cuts that were unwisely removed by TCJA, and preserves the TCJA provisions that made the U.S. competitive internationally.

The benefit of a competitive business tax system for the working class was proven after TCJA. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. economy experienced unprecedented growth and prosperity. Businesses increased domestic investment by an estimated 20% as a direct result of TCJA’s business tax changes. More business activity led to more jobs, with unemployment in the U.S. reaching its lowest level in 50 years after TCJA. A stronger job market brought higher wages, with wages increasing faster after TCJA than at any point since the Great Recession, benefitting those with the lowest incomes the most. Ultimately, real median household income spiked dramatically by 2019, two years after TCJA’s passage.

Conclusion

With discussion of a second or third reconciliation bill for this Congress already underway, it is important to recognize what OBBBA gets right and what it gets wrong. Making permanent some of TCJA’s most important provisions—individual income tax cuts and pro-growth business tax changes—undoubtedly makes OBBBA a laudable achievement. OBBBA will increase gross domestic product (GDP) by an estimated 1.2% in the long-run, with much of that attributable to full expensing. The bill also includes tax incentives to encourage small business growth, such as an expansion of the capital gains tax exclusion for sale of qualified small business stock (QSBS).

To help offset the reduction in federal revenue caused by tax cuts, OBBBA enacts sensible spending reforms and subsidy cuts that lay new groundwork for serious fiscal reform to occur in the future. To be clear, this legislation could have done more to reduce costs, and fell short of a promised $2 trillion in deficit reduction.

Now that permanent tax cuts are out of the way, it’s time to make serious spending reductions through reconciliation, rescissions, and research-guided reforms.