Key Facts

- California, New York, Illinois, and other states with high tax burdens continue to hemorrhage taxpayers and tax revenue, while Florida remains the undeniable winner from movement of taxpayers and their dollars from state to state.

- In the last decade, New York lost $111 billion in net adjusted gross income (AGI), California lost $102 billion, and Illinois lost $63 billion to interstate migration.

- On the other hand, Florida gained $196 billion, and Texas gained $54 billion.

The American federalist system is a double-edged sword for states like New York, California, and Illinois. While they have the power to set their own tax policies, taxpayers retain the freedom to leave for greener pastures should tax burdens in those states become overwhelming. And, while these states may bemoan the negative effects of their former residents voting with their feet, this competition for taxpayers is one of the most valuable tools in taxpayers’ arsenals to get their individual voices heard — though a simple majority gets a state legislator elected, residency decisions are made at the household level.

Given the years of data and examples showing the same trends, most state-level policymakers understand that the competitiveness of their state’s tax code has an impact on interstate migration. But exactly the scope of that impact remains difficult to contextualize. Economic and budgetary pain from out-migration is a slow bleed, and can too easily become the norm for states locked into tax-and-spend death spirals. Therefore, this analysis puts numbers to interstate migration phenomena not just in terms of residents gained or lost, but also in terms of the impact on states’ bottom lines.

Interstate Migration over a Decade

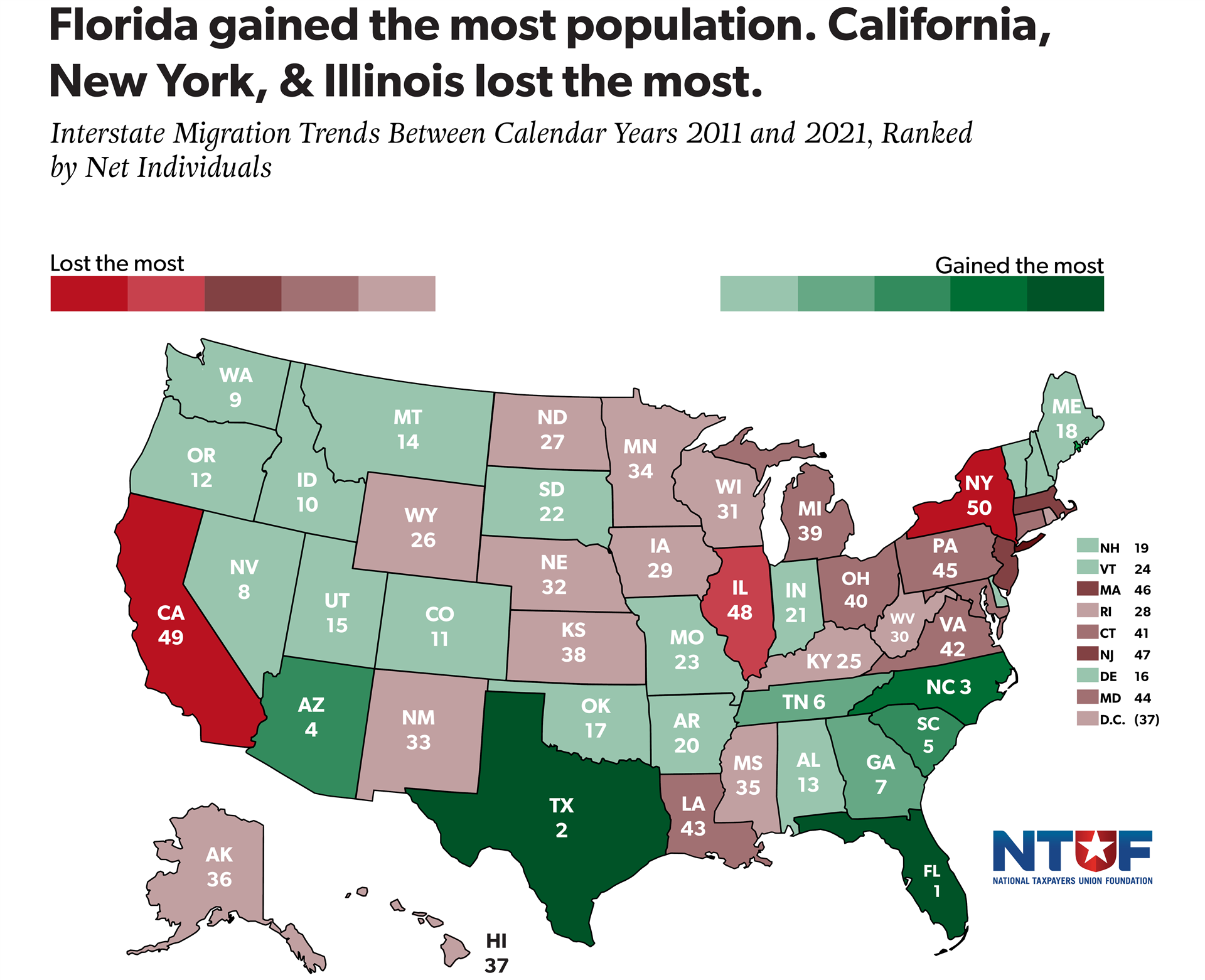

This map shows the effect of interstate moves between calendar years 2011 and 2021, ranked by net individuals.

Source: ntu.org/Population

The seven states gaining the most AGI because of net interstate migration and the seven states losing the most to interstate migration in the most recent IRS data release are the same as those over the previous decade of IRS releases, albeit in slightly different orders. Absent policy changes, these trends are sticky, and represent a significant problem for states on the wrong end of the list.

The exceptions prove the rule. Washington state, for example, ranks 10th over the last decade, gaining a net of nearly $11 billion in AGI over that period of time. That has changed in recent years as Washington has begun to increase tax obligations, with the state ranking 40th in the most recent year. Not even accounted for here is billionaire Jeff Bezos’s recent move from Seattle to Florida, which took place in 2024. Unfortunately, Washington does not appear to be learning the lesson anytime soon, with Gov. Jay Inslee proposing a new 1% tax on wealth.

Revenue Impacts

While net returns and AGI are important metrics for quantifying the impact of domestic interstate migration on states, they can often seem abstract. A steady outflow of residents to other states is an abstract problem to a state legislator, but the need to balance a budget is a practical one. Therefore, legislators are strongly incentivized to prioritize short-term revenue boosts over making their states’ tax codes more attractive for the long-term.

However, interstate migration does impact a state’s budget in both the short and long term. To quantify this, we use effective state-local tax rates as calculated by the Tax Foundation — this accounts for the fact that some states prefer to rely more on local sub-jurisdictions to collect revenue than others.

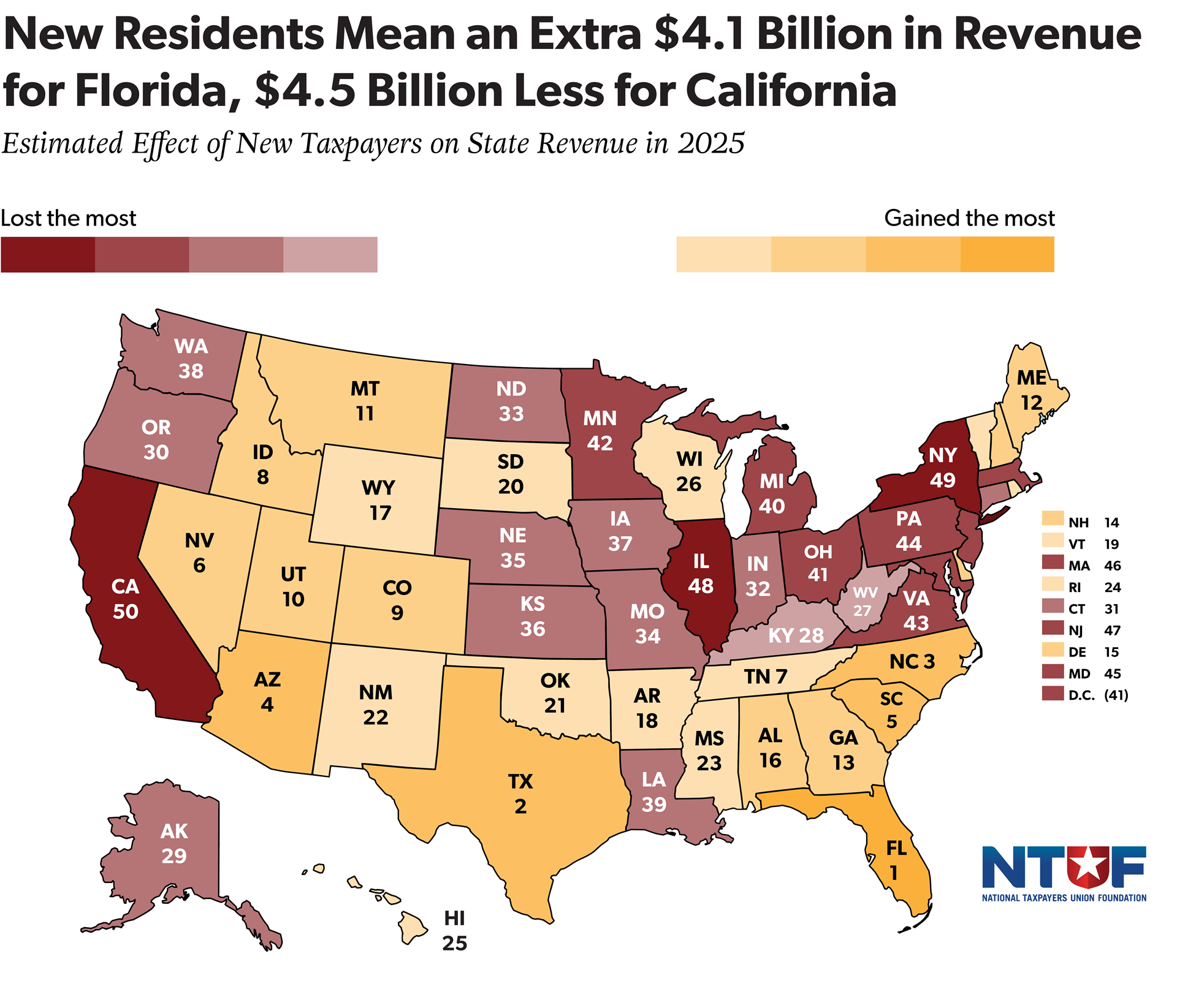

This map shows the effect of interstate moves on each state’s estimated revenue in 2025 if current trends continue.

Source: ntu.org/Revenue

While estimated revenue outcomes include local-level revenues and are not strictly comparable to state budgets, they should give some context for how much of a direct revenue impact interstate migration can have.

Revenue outcomes from interstate migration are cumulative. California loses $4.5 billion from excessive out-migration not just this year, but next year and every year thereafter. These cumulative effects can be substantial. New York, for example, lost $111 billion in net AGI between 2011 and 2021.

A cumulative accounting that takes into consideration taxpayers who left the state earlier in the decade shows that the true impact on New York’s revenue over the course of the decade was more like $68 billion, a truly massive drain on the state’s coffers.

It is true that this does not account for the fact that taxpayers no longer paying taxes are also no longer drawing upon government services. However, estimated revenue changes are driven primarily by the movement of high-income earners, who tend to pay far more in taxes than they receive back in government services.

Discussion

In recent years, states have increasingly emphasized tax competitiveness. Since 2021, 27 states have reduced the rate of a major tax, while states continue to pursue reforms to make their tax codes more attractive to remote workers. Often, these reforms are simply good policy, enabling taxpayers to put their own money or time to more productive uses. But a competitive tax code offers a clear, direct, and tangible benefit to states — taxes matter to taxpayers, and they tend to prefer to live in states that subject them to lower tax burdens.

But while that truism is straightforward enough, the scope of that impact is up for debate. Advocates of higher taxes tend to be dismissive of the impact of taxes on interstate migration, terming the impact of tax-based migration “minimal.” And certainly, there are plenty of reasons taxpayers move to other states that have nothing to do with the tax rates that they face. Factors frequently cited include family, weather, housing availability, education, transportation infrastructure, employment opportunities, and cost of living generally.

While tax rates are not the only reason taxpayers move to different states, it is hard to deny that they play a substantial role in where taxpayers decide to live. When looking at broader trends, the clear pattern is that taxpayers move from states with higher tax burdens towards states with lower ones. Tax rates explain this trend better than any other explanation put forward, from weather to the cost of housing.

Unlike other states that have sought to respond to these trends by making their tax codes more competitive, some states like New York and California have aimed to make up for lost revenue from taxpayer interstate migration by attempting to assign more tax obligations to nonresidents. This tendency has made interstate commerce more fraught from a tax perspective, often making tax compliance far more complicated and time-consuming, as taxpayers and small businesses are expected to file and comply with tax obligations in different states and localities around the country. The increased time burden these obligations entail has proven at times to be a greater threat to affected taxpayers and businesses than the obligations themselves.

States seeking to tax more nonresidents to make up for lost revenue from departing residents are learning exactly the wrong lesson. The ability of overtaxed taxpayers to migrate is one of the most powerful tools that taxpayers have to counter the impulses of tax-and-spend politicians, even in traditionally high-tax states. States replacing lost revenue from migrating residents with increased revenue from nonresidents is essentially taxation without representation.

Fundamentally, there should be a relationship between taxes and the government services they pay for. This relationship does not need to be (and realistically cannot be) dollar-for-dollar — wealthier taxpayers pay more taxes for fewer government services, nonresidents can incur tax obligations for legitimate reasons, and so on. But states intentionally targeting nonresidents are stretching the connection between tax obligations and services further. When tax obligations begin to feel less like a just, if unpleasant, cost of a functional society and more like a shakedown, it has a deleterious effect on the entire system.

Conclusion

Year after year, IRS interstate migration data continues to tell a familiar story — taxpayers are leaving high-tax states for low-tax ones. But, as low-tax states have sought to become more competitive and high-tax states have doubled down on tax-and-spend policies, these trends have become even more pronounced.

Even so, the negatives for states losing residents to interstate migration have remained largely abstract — a nebulous population decrease can appear less pressing than the need to balance the books today. But, even for a state as big as California, $4.5 billion in lost tax revenue due to just a single year of interstate migration is real indeed.

States should recognize that a tax code that attracts businesses and workers and allows them to thrive is the path to long-term prosperity. Meanwhile, states on the losing end of the interstate migration battle should stop trying to make up for lost revenue with higher taxes on residents and nonresidents alike, and start trying to fix what is making their residents leave in the first place.