Key Facts:

- A ballot measure that may go before California voters in November would propose a “one-time” 5% tax on the total wealth of California billionaire residents.

- Billed as a way to raise $100 billion in easy revenue, the threatened tax has already motivated wealthy individuals worth a combined $1 trillion to relocate out of the state, turning California’s steady trickle of wealthy individuals leaving for Texas and Florida into a flood.

- Even were it to pass, the tax suffers from numerous design defects and would likely be struck down in court on numerous constitutional grounds.

California has managed to outdo itself. Not only might the state lose revenue from its latest proposal to tax the rich—it might have done so already.

The 2026 Billionaire Tax Act is not law, but a proposed ballot measure that organizers are gathering signatures to place on California’s November 2026 ballot. It would impose a “one-time” 5% tax on the wealth of high-net worth individuals who resided in California as of January 1, 2026. The proposal raises serious questions about damaging California’s competitiveness with other states, whether it can be administered without a more extensive tax enforcement apparatus, how and how quickly good-faith disagreements on valuation will be resolved, how it will harm company valuations and pressure small businesses toward consolidation, and whether it can pass constitutional muster.

Issue #1: Harm to California Competitiveness

States like California and New York are continuing to find that, over the long term, a steady flood of tax increases erodes the state’s tax base as fed-up taxpayers flee for greener pastures. But at least advocates of endless new tax proposals can hang their hats on the fact that, usually, new tax increases do raise additional revenue in the short term. Proponents of the ballot initiative estimated that the new tax would raise $100 billion in additional revenue.

Yet even the hopes of a temporary sugar high are rapidly diminishing. Wealth taxes at the state level suffer from one distinct drawback that even their (still quite inadvisable) federal-level counterparts do not: the fact that it is extremely easy for wealthy individuals to pack up and move elsewhere.

The list of billionaires rapidly cutting ties with California ahead of that January 1, 2026, deadline includes numbers 2 and 3 on the Bloomberg Billionaires List: Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Other notable names include Peter Thiel and David Sacks. Billionaire Chamath Palihapitiya estimated on X recently that more than $700 billion has already left the state, guessing that as much as $1 trillion—including, possibly, his own substantial estate—may end up leaving California before the year is out. That number does not even account for Mark Zuckerberg, who was recently the latest example to head to Florida’s “Billionaire Bunker.”

For reference, the $100 billion in hoped-for revenue comes from a calculation by academics Brian Galle, David Gamage, Emmanuel Saez, and Darien Shanske, essentially taking $2.2 trillion in California billionaires’ wealth from Forbes estimates, assuming just 10% avoidance, then multiplying that by 5%. If $700 billion in billionaire wealth has indeed already fled the state, their revenue numbers are already $25 billion too rosy.

And even though the January 1 deadline has passed, the bleeding is likely far from finished. Even should the ballot measure pass, the retroactivity provision assessing the tax based on residency on January 1 is certain to face constitutional challenges based on the Due Process Clause. Concerned billionaires who missed the January 1 deadline still have a strong incentive to get out of the state as soon as possible, as a court decision striking down the retroactivity provision could wipe away tax bills from those who leave soon.

This may be why Governor Gavin Newsom has come out strongly against the proposal. Newsom has pointed to the cavalcade of high-profile departures as his reason, stating “This is my fear. It’s just what I warned against. It’s happening.”

Progressives who seek to realize policy aspirations that have stalled in Washington, DC by taking them to bluer state capitols are simply not reckoning with this fact. Even the most dyed-in-the-wool tax advocate needs to consider the impact that new state-level tax hikes will have on the state’s ability to raise revenue in the future.

In past years, we have seen sustained, substantial outmigration by wealthy individuals from the state of California. California loses more wealthy individuals to outmigration than any other state already, a fact which subjects California budget analysts to a giant sucking sound of their own as every year taxable income heads to greener pastures.

In the decade leading up to the latest IRS-released data, covering moves to other states during 2021, California lost a net of 1.6 million individuals to other states. That translates to an evaporating tax base, with the state losing an estimated $12.7 billion in state and local revenue during those years. Yet these trends are accelerating—NTUF recently estimated that net migration will lose the state $4.5 billion in 2025 alone.

The numbers California is facing here may well make that flood look like a trickle by comparison. The nonpartisan state legislative office likewise analyzed the impacts of the tax back in December, estimating an “ongoing decrease in state income tax revenues of hundreds of millions of dollars or more per year.” Even that likely understated loss would represent significant, sustained erosion of the most reliable revenue source from a state that relies heavily on volatile revenue sources.

Reversing it may not be as simple as voter rejection in November. One thing that people often miss when discussing the impact of tax policy on interstate migration is that taxpayers respond not only to implemented tax changes, but also to the political climate. Even if this ballot measure does not pass, wealthy individuals may well decide that they no longer want to live in a state where legislators and activists argue over the best ways to seize their wealth to fuel chronic overspending. Migration trends, already so ominous for states like California and New York, are likely only to accelerate.

Seventeenth-century French finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert is supposed to have defined taxation as “the art of plucking the goose so as to obtain the greatest amount of feathers with the least amount of hissing.” Thus far, this proposed tax is succeeding in maximizing only the hissing, with no feathers at all to show for it.

Issue #2: Poorly Designed “Tax Cliff” and Confusing Asset Calculation

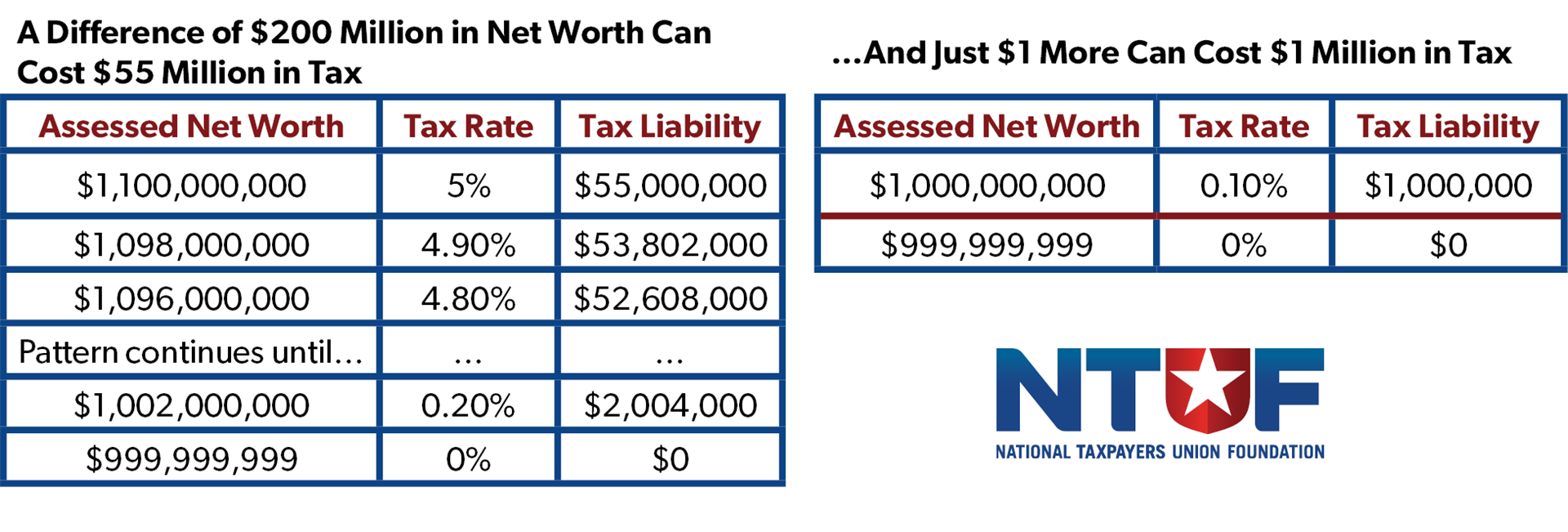

The new, one-time 5% tax is described as an “excise tax on the activity of sustaining excessive accumulations of wealth.” The tax would apply to the assessed net worth (henceforth referred to as ANW) of California taxpayers with ANW exceeding $1 billion. The tax rate phases out between $1.1 billion and $1 billion, dropping the tax rate by 0.1% for each $2 million that the taxpayer’s ANW drops below $1.1 billion. To illustrate:

This phase-out is significant and abrupt for taxpayers with ANW in this range—a taxpayer with a net worth of $1 billion would owe a 0.01% tax on their ANW, or $1 million in tax. A taxpayer with a net worth of $1.1 billion would owe 55 times as much.

ANW would consist of a taxpayer’s total assets minus:

- Recourse debts, including those held under a sole proprietorship (not those held by a taxpayer’s stake in a partnership, LLC, or other business interest). Non-recourse debts can only reduce a taxpayer’s ANW to an amount equivalent to the assets serving as collateral.

- Debts owed to related persons would not reduce a taxpayer’s ANW.

- Tangible personal property located outside California for at least 270 days in 2026, unless relocated temporarily “with a substantial purpose of avoiding tax”

- Qualified pensions

- Up to $10 million in Roth IRA or other Roth-type retirement accounts

- Up to $5 million in total value of assets such as art, vehicles, collectibles, etc.

The proposal also includes detailed rules on establishing the valuation of privately-held assets. Affected taxpayers can choose between paying their entire tax liability in the 2026 tax year, or paying in five equal installments, with the remaining liability subjected to a 7.5% “deferral charge” each year.

Issue #3: Administrative Apparatus Would Be Built Up for a “One-Time” Tax

A major reason why most of the dozen or so other OECD countries that once had a wealth tax in place have since abandoned it is the complexity of administering such a tax. Only Norway, Spain, and Switzerland currently still levy taxes based on net wealth.

Since this is ostensibly a one-time tax, California would have to build up the enforcement apparatus to crack down on avoidance for a tax that is not even permanent. By the time the institutional knowledge on administering this new type of tax had been developed, there would no longer be any need for it.

Of course, it may not be the case that this is truly a one-time tax. But that brings things back to the problem of out-migration—just as tax enthusiasts would be likely to return to this well in the future, so too will affected taxpayers expect them to do so, encouraging even those prepared to take a one-time hit to their wealth to seek the exits in the near future.

Issue #4: Valuation Methods Create Unintended Consequences and Punish Good-Faith Disagreements

“Book Value” Doesn’t Translate Well to Tech Unicorns

Broadly speaking, the language of the initiative establishes an individual’s net worth based on “the fair market value of each asset owned by a taxpayer [which] is the price at which the asset would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither being under any compulsion to buy or to sell, and both having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.”

Such directives may well suffice for assets such as publicly traded stocks, but other types of assets pose much more of an issue. The initiative requires that stake owners use the “book value of the business entity according to generally accepted accounting principles as of the end of the tax year” plus “7.5 times the annual book profits of the business.”

Ironically, this methodology—so popular among progressives because it allows them to exclude deductions they created from the equation—is likely to result in minimal revenue from holdings in California’s tech startups, many of which operate at a loss annually and hold value primarily due to the potential for future earnings. Their primary assets (a dedicated user base, intellectual property, brand recognition, future monetization potential) are absent from a book value calculation. Tech makes up nearly 80% of the collective wealth of California billionaires, and these businesses are disproportionately revenue-light and potential-rich.

Not subjecting that perceived future value to present-day taxation is for the best in terms of good tax policy, but good tax policy left the station around the words “wealth tax,” and it’s very bad for translating Forbes net worth into revenue.

Punishing Good-Faith Valuation Disagreements

The difficulty of valuing privately-held assets is one of the central drawbacks of wealth taxes in general. Arguably even more difficult than valuing stakes in privately-held business ventures is valuing other miscellaneous assets such as art, collectibles, intellectual property, and so on.

Throughout, the drafters of this initiative repeatedly attempt to cut through this Gordian knot with a poleaxe—attempting to prevent undervaluations not through investment in the kinds of careful but painstaking bureaucracy necessary to arrive at relatively accurate valuations, but rather through erring always on the side of overvaluation.

The best example of this is the harsh penalties applied to taxpayers for “undervaluation”—by which the initiative’s language means “valuation lower than what the state’s Franchise Tax Board (FTB) arrived at. Taxpayers face a penalty of 20% if they are deemed to have understated their liability by the greater of $1 million or 20%, and a penalty of 40% if they are deemed to have understated their liability by the greater of $10 million or 40%.

While a valuation delta in the millions of dollars may appear to be a high bar to clear before penalties come into play, good-faith differences in the valuation of such assets can easily exceed this amount. For instance, consider the example of a dispute between the IRS and the heirs to Michael Jackson’s estate for estate tax purposes.

When Jackson passed away in 2009, his estate valued the rights to use his image and likeness at $2,105—a valuation certified by a valuation expert who noted the fact that the decedent had a decidedly negative public image by the time of his death. The IRS, on the other hand, valued it at $434 million.

Resolving this valuation dispute took 12 years, at which time a judge handed down a 271-page decision valuing the rights at $4 million. While this was substantially more than the estate initially valued these rights at, it was $430 million less than the IRS valuation.

The point is that neither the taxpayer nor the enforcement agency must necessarily be acting in bad faith to arrive at such wildly different valuations of the same asset. The IRS’s valuation was based on the image of the “King of Pop” who was one of the most famous people in the world at the time of his death. The taxpayer’s appraiser, on the other hand, focused more on the scandals that led to the deterioration of his public image. Two reasonable individuals acting in good faith could easily arrive at such vastly different conclusions.

Nevertheless, had this dispute taken place in California under this wealth tax, the FTB would have assessed an $8.68 million “gross understatement of tax” penalty on the taxpayer—more than double the amount that the court decision ultimately set the value of the underlying asset at.

Not only does this penalty apply to the tax, under the language of the initiative, the FTB can also choose to apply a penalty of up to 4% of the amount of overstatement to the appraiser as well. This penalty is actually even more draconian than the one applying to the taxpayer, since it applies to the valuation that has been deemed to be understated rather than the liability.

Again, using the facts of the Michael Jackson case, where the $2,105 valuation was submitted by a certified appraiser, it would have amounted to a staggering $17.4 million penalty assessed on the appraiser, who is by no means a billionaire. This would almost certainly lead to that individual’s total financial ruin simply for doing his job and, in good faith, certifying an appraisal that the tax authorities happened to disagree with.

Even were the FTB to decline to exercise the authority to levy such ruinous penalties, the mere possibility would likely be more than enough for appraisers to only certify valuations that they were confident that tax authorities could not possibly consider to be understatements.

In other words, the clear intent of these penalties is to prevent valuation disputes by making it unreasonably financially dangerous for any appraiser to back a taxpayer’s valuation position, even if they believe it is correct and defensible. It is a most cynical attempt to sidestep a major drawback of wealth taxes by ensuring that the tax authorities’ position in any valuation dispute wins by default.

Issue #5: Small Businesses Pressured toward Corporate Consolidation

Another issue with this proposal is the potential for corporate consolidation. NTUF has illustrated in the past the extent to which wealth taxes are particularly punitive to entrepreneurs and start-up founders, who are often asset-rich and liquidity-poor. For these individuals, paying their wealth tax bill requires liquidating some of the shares of the companies they founded—along with facing capital gains taxes on the shares sold to pay their wealth tax bill as an added sucker punch.

This means that some founders have no choice but to put up for sale control over these valuable and disruptive startups—something previously out of the reach of larger and more established players. What’s more, the market gets flooded with shares from startup founders urgently seeking liquidity all at once, further driving down the value of the shares that can be snapped up.

But another bizarre valuation choice made by the initiative’s architects puts this existing dynamic on steroids. The initiative backstops the valuation of ownership stakes in businesses that are not publicly traded based on the share of voting rights conferred by those stakes. As the initiative states:

For any interests that confer voting or other direct control rights, the percentage of the business entity owned by the taxpayer shall be presumed to be not less than the taxpayer's percentage of the overall voting or other direct control rights.

In other words, the valuation of ownership stakes in privately-held businesses is based on either the percentage of ownership shares or the percentage of voting shares, whichever is greater. As Jared Walczak of the Tax Foundation notes, this potentially subjects startup founders who maintain controlling voting rights to punitive and disproportionate tax rates. Walczak points to the example of Tony Xu, founder of DoorDash, who would face a tax liability of greater than 100% of the value of his DoorDash shares based on the fact that he maintains a 57.6% voting stake.

Wealth taxes in general harm entrepreneurs and incentivize corporate consolidation. This initiative manages to do so while also punishing startup founders who sold shares while preventing control over their achievement from passing into the hands of others.

One way to address this kind of inherent bias against wealthy individuals who have low liquidity is to allow taxpayers to spread the tax liability out over multiple years, allowing them to liquidate the necessary assets without engaging in a fire sale. Yet, while the language of the initiative allows for this, it also assesses a 7.5% fee on the remaining unpaid balance each year, while also requiring that any taxpayer who enters into the deferral program pay either their entire tax liability in year one or pay in five equal installments.

This amounts to a 30% increase in an affected taxpayer’s overall tax liability should they opt for the deferred payment plan. While inflation and passive investment returns mitigate this effect somewhat, it remains an effective tax increase that affects low-liquidity billionaires exclusively.

Issue #6: Legal Vulnerabilities

Should the initiative gain enough signatures to appear on the ballot in November, and then should it subsequently be passed, then the battle would simply move from the court of public opinion to the court of law. The language of the ballot initiative appears to violate the Constitution in several ways.

Retroactivity

The language of the initiative determines liability for the wealth tax based on a taxpayer’s residency as of January 1, 2026, despite the fact that voters will not vote on the initiative before November 2026. This likely represents a Due Process Clause violation, as taxpayers would be assessed a tax based on their residency at a time when such a tax did not and never had existed.

Courts have historically accepted retroactive application of taxes, but only in very limited circumstances. For instance, in United States v. Carlton (1994), the Supreme Court upheld a 1987 Congressional amendment to a 1986 law establishing a new estate tax deduction because it determined that the 1987 amendment was intended as a clarification of the 1986 law’s intent at the time of drafting. At the same time, the court in Carlton was careful to distinguish between the retroactive application of an amendment enacted in a timely fashion and intended to clarify the clear intent of a previously enacted law, as opposed to the retroactive application of a “wholly new law.”

Proponents of the initiative will argue that the “rational basis” for the retroactive application in this case is the need to prevent taxpayers from being able to avoid the assessments by leaving the state before it came into effect. If the courts determine that taxpayers’ fundamental due process rights are implicated, however, a stricter standard of scrutiny would apply. The fact that the tax at issue is an entirely new one makes California’s argument far harder to defend.

Another challenge for California, should it have to defend such a provision in court, is that it would have to argue that the legislative purpose being served by retroactivity provisions is the denial of what has long been established as a fundamental right: the freedom to travel and move between states. In Crandall v. Nevada (1868), the Supreme Court struck down a Nevada tax on residents leaving for other states because it restricted this fundamental right and impeded interstate commerce. Arguing that preventing taxpayers from exercising this right is a legitimate reason to assess a brand-new tax retroactively would be a difficult hill to climb for the state’s lawyers.

Apportionment of Out-of-State Wealth to California

Standard apportionment under the initiative assigns 100% of a taxpayer’s wealth to the state of California, without accounting for the location of a taxpayer’s assets or the residency of the taxpayer following January 1, 2026. This extremely aggressive apportionment standard should face strong challenges under the Due Process and Commerce Clauses.

Under the Complete Auto test, a tax must:

- Be applied to an activity with a substantial nexus to the taxing state,

- Be fairly apportioned,

- Not discriminate against interstate commerce, and

- Be fairly related to services provided by the state.

This tax may earn the rare distinction of violating all four prongs of the Complete Auto test at once. Properties and business interests located outside the state clearly have no substantial nexus to California (prong one), apportioning 100% of assets to California is not “fair apportionment,” taxation of assets properly apportioned to other states harms interstate commerce by improperly pilfering another state’s tax base, and taxation of assets located outside the state clearly is unrelated to services being provided by the state.

Proponents of the initiative will argue that the initiative allows for alternative apportionment in cases where the standard apportionment would violate either the California or United States constitutions. This “alternative apportionment” amounts to petitioning the FTB to accept an alternative apportionment standard, with the burden of both proving that the standard apportionment is unfair and of suggesting alternative apportionment “that is practicable to administer.”

This is not a sufficient alternative to escape legal challenge. Taxpayers are not responsible for designing their own apportionment formulas to protect California when its preferred apportionment formula of “everything you own is apportionable to California” proves unconstitutional.

Takings Clause

It is rare for a tax to potentially implicate the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment, as courts have broadly upheld taxes in the face of Takings Clause challenges. While taxpayers never receive a one-to-one ratio of government services in return for their tax payments, the proper functioning of society is generally accepted by courts as sufficient compensation for taxes.

The small caveat is that the burden of payment for services that affect the broader public cannot be exclusively placed on a small group of individuals. The burden can be concentrated among the wealthy, as it currently is, and it can take the form of progressive tax rates. The distinction between a tax and a taking is the extent of this concentration—as legal scholar Calvin Massey argues, funding our government via a 100% income tax on one individual would certainly represent a taking (not to mention be impossible), so it becomes a matter of degrees.

In this case, the initiative is explicitly seeking to fund health care costs, something which affects all Californians, via a tax that the initiative’s backers estimate will be paid by about 200 people. Hyper-targeting such a limited group of individuals to finance services benefiting the entire state may well be an extreme enough case to implicate the Takings Clause. As the Supreme Court wrote in Armstrong v. United States (1960), the Takings Clause “was designed to bar Government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole.”

Excessive Fines Clause

The Excessive Fines Clause of the Eighth Amendment has taken on new relevance recently after years of being largely absent from Supreme Court jurisprudence. In Hennepin County v. Tyler (2023), the 9-0 majority found that Minnesota’s Hennepin County violated the Takings Clause because, when it seized and sold a taxpayer’s condominium to pay her property tax debt, it kept the excess beyond the unpaid property taxes instead of returning it to the taxpayer.

The majority opinion took no position on the taxpayer’s Excessive Fines Clause claims because she won on Takings Clause grounds, but a two-justice concurrence argued that Hennepin County’s action represented an excessive fine.

In this case, provisions assessing exorbitant penalties upon taxpayers for “understating” liability likely represent excessive fines. These provisions are discussed in more detail above, but they impose substantial additional penalties on taxpayers who arrive at different valuations of subjective and difficult-to-value privately-held assets. Not only do these penalties apply to taxpayers themselves, they can also apply to appraisers who certify valuations that the FTB deems to be understatements. Such penalties, which can easily amount to multi-million dollar assessments for good-faith valuation disagreements, should easily qualify as excessive.

Conclusion

California has been suffering a steady stream of out-migration, particularly by its wealthiest taxpayers, for some years now. It is a reflection of just how much of an unforced error this ballot initiative is that it is causing such a drastic and likely irreversible hit to the state’s tax base before it is even voted on.

Even the most ardent believer in the benefits of higher taxes and government spending should recognize that tax policy at the state level is fundamentally different from tax policy at the federal level. Moving from one state to another is simply far easier and less impactful, particularly for the wealthiest taxpayers who have the means to do so, than immigrating to another country. Consequently, state policymakers in high-tax states need to understand that they lack the leverage to constantly be increasing tax rates on their residents without fiscal consequences.

This also should cast broader efforts by states to export tax burdens across their borders to nonresidents in a different light. These efforts are not just cynical ploys by states like California and New York to flex their size and economic influence to bully nonresidents into paying into their coffers—they are direct responses to taxpayers voting with their feet to live in lower-tax states, attempts by California and New York to escape the consequences of their actions.

Competition between states is the only effective check that taxpayers have on state policymakers who treat budgeting as a matter of setting their desired spending levels, then finding ways to seize the revenue to pay for it. California is about to find that out the hard way.