The latest version of the Senate’s reconciliation package, now known as the Inflation Reduction Act, would prohibit implementation of a regulatory rule that dates back to 2019 and has never been implemented. The Trump-era rule was intended to limit the use of rebates offered by pharmaceuticals that the former administration argued were driving up out-of-pocket costs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) conducts cost estimates of major rules and includes them in its official baseline. CBO estimated that the rule would end up increasing Medicare and Medicaid costs by an average of $21 billion per year through 2031. Legislative attempts to delay or repeal it are scored as large savings relative to CBO’s baseline, even though the rule has not been implemented and would be subject to significant legal challenges if it ever was implemented.

The rule was supposed to have gone into effect in 2021 but was delayed by a court order until 2023. Since then, two acts of Congress further delayed implementation of the rule until 2027, while other proposed bills have also sought to either delay or prohibit the rule.

Below is a timeline of actions and proposals related to this rule. Given the chaotic history of the rule and the many attempts to legislatively delay it as a means to paper over large spending increases, it is dubious to claim that repealing it would have a real-world impact on reducing government spending and deficits.

Timeline

January 2019

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed the rule.

May 2019

CBO estimated that the proposed rule would increase federal spending by $177 billion over ten years. Because the rule was still under review, “CBO assumed that there was a 50 percent chance that the proposed rule would be enacted and a 50 percent chance that “no new rule like the proposed rule would be enacted.” CBO split the difference on the basis of that assumption and added the proposed rule to its baseline at a cost of $89 billion.

August 2019

CBO reported that because the administration withdrew the proposed rule, it removed $85 billion from its Medicare Part D projection and $4 billion from Medicaid projection.

October 2019

The proposed rule was reinstated.

November 2020

The rule was finalized, with the regulations set to go into effect in January 2021.

March 2021

The HHS Inspector General issued a notice that the rule’s implementation had been delayed due to a court order until January 1, 2023.

November 2021

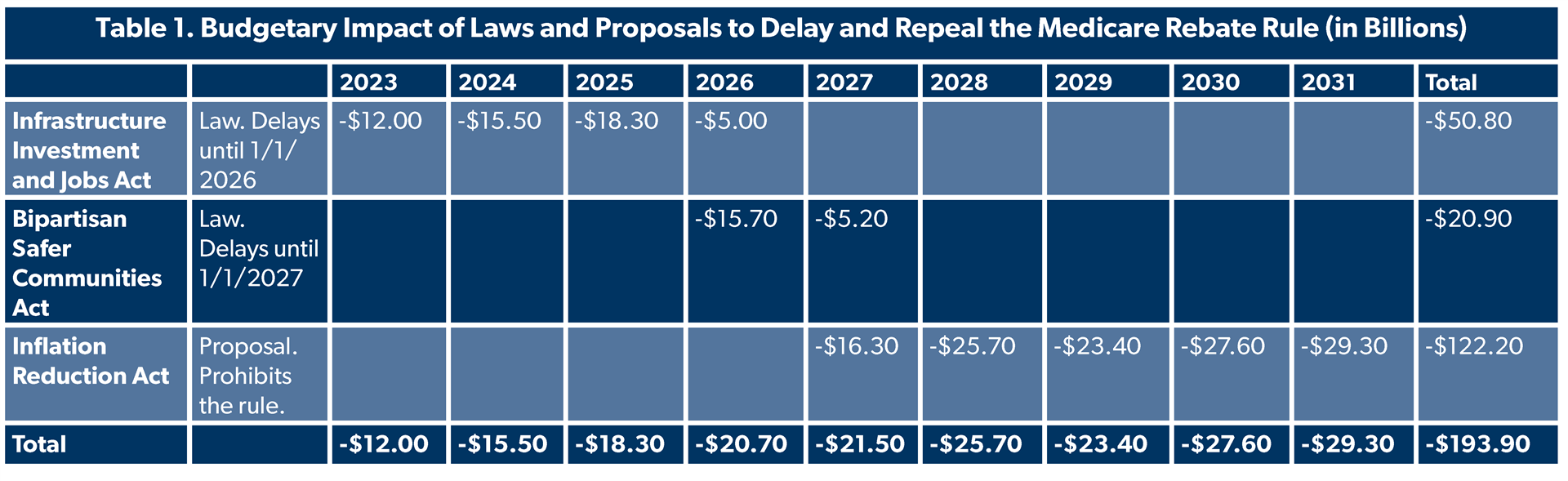

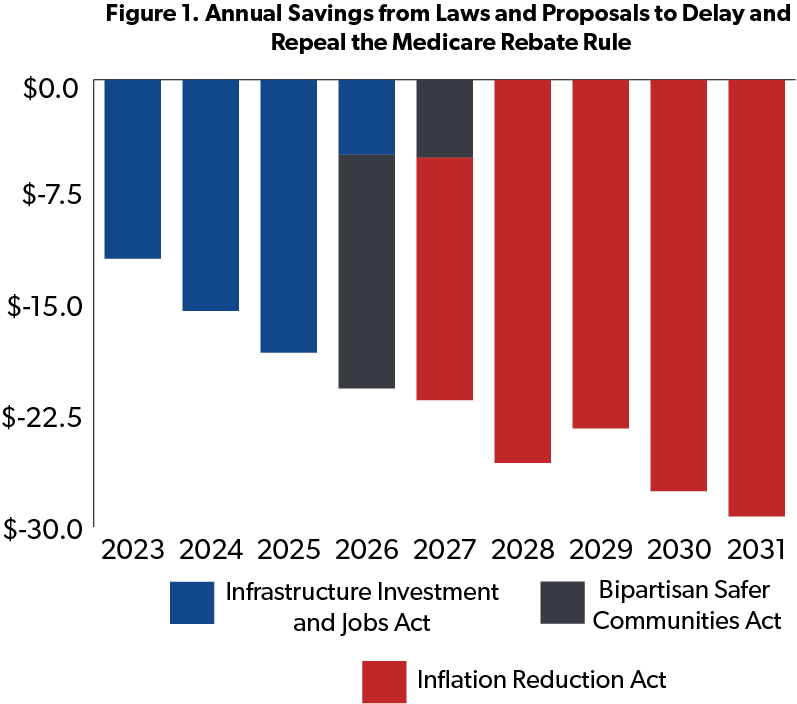

Congress enacted the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which delayed implementation of the rule until January 1, 2026. CBO estimated this would reduce outlays $50.8 billion from FYs 2023 through 2026.

November 2021

The House passed the Build Back Better Act, which would repeal the rule after January 1, 2026. CBO said this would reduce outlays by $142.6 billion from FYs 2026 through 2031. Unlike the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Build Back Better Act has not become law.

March 2022

The House passed the Affordable Insulin Now Act, which would delay implementation of the rule until January 1, 2027. CBO estimated this would reduce outlays by $20.4 billion, a net of $15.0 billion in 2026 and $5.4 billion in 2027. The Affordable Insulin Now Act has not become law.

April 2022

The Make Medicine Affordable Act introduced in the House would repeal the rule.

May 2022

The Restaurant Relief Act introduced in the Senate would delay implementation of the rule until January 1, 2028.

June 2022

Congress enacted the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which delayed the implementation of the rule until January 1, 2027. CBO estimated this would reduce outlays by $20.9 billion from FY 2026 through 2027.

July 2022

The newest versions of the reconciliation package — as posted by the Senate Committee on Finance on July 6 and then in the initial text of the Inflation Reduction Act as posted on July 27 — would repeal implementation of the rule. CBO estimates this would reduce outlays by $122.2 billion from FY 2027 through 2031.

Analysis & Conclusion

It is these ups and downs and delays that led many people to consider the delays of this rule, and now its proposed repeal, as a budgetary gimmick. Repealing the rule will save money from CBO’s baseline projection by ending a regulation that no one seems to want, but it leaves existing government spending in place.

For an illustrative example, there are two outlay programs with a fiscal impact this year that is comparable to the annual estimate for repealing this rule: the National Aeronautics and Space Administration is expected to spend $24 billion this year and the Department of Transportation’s Transit Infrastructure grants program will spend $21 billion. With the Medicare Rebate Rule, Congress is conjuring up phantom savings about the size of these programs.

For a genuine source of savings, lawmakers could draw on NTUF and U.S. PIRG Education Fund Common Ground project that lists budget options to cut nearly $800 billion from the ten-year deficit by repealing and reforming current budget programs.

It is also worth noting a concern about the accuracy of the cost estimate of the rule. CBO did not delve deeply into the points of uncertainty in the score (a practice the agency undertook with more frequency starting in 2020), but it did note that a consulting firm analyzed several different scenarios of stakeholder responses to the rule. Estimates from these alternative scenarios ranged from a savings of almost $100 billion to a cost of $139 billion.

If lawmakers engaged in honest budgeting, they would repeal the rule and ask CBO to assume it would not go into effect; a safe assumption given the history of this policy. This would cancel the rule that no one seems to want and leave the on-paper savings out of cost estimates.

There is precedence for this. For a related example, CBO’s current law baseline still includes receipts amounting to $390 million per year from nuclear waste fees even though, by practical policy, these fees are not being collected. CBO “estimates the total amounts that would be collected if fees were fully reinstated and includes 50 percent of those amounts in its baseline.” The House Budget Committee instructed CBO to exclude these fees as it scored a proposal to reform nuclear waste programs.

Alternatively, lawmakers could change the scoring rules to discount the savings in estimates of rules that are delayed before being implemented. This would be similar to what CBO currently does with proposed rules and the nuclear fees. Increasing the discount each time a delay is implemented would effectively put a time limit on the ability of lawmakers to use budgetary tricks like this. As the score is zeroed out, the rule should be considered lapsed.

Without scoring reform, it is conceivable that the executive and legislative branches could scheme up other proposed rules to pump up CBO’s baseline and then claim savings by using the same process we’ve seen with the rebate rule.