(pdf)

San Francisco has pushed productive businesses away in recent years by targeting e-retail and digital businesses with ever-increasing tax burdens. But rather than learning a lesson from these consequences, it may soon double down on this strategy if a measure set to appear on the ballot in November is passed into law.

Proposition K and Its Effect on E-Commerce

Proposition K would attempt to fund a Universal Basic Income (UBI) on the backs of e-commerce businesses, particularly smaller ones, by raising the gross receipts tax (GRT) rates that businesses selling into San Francisco would face. Meanwhile, brick-and-mortar retailers in San Francisco would be exempt from the tax increase.

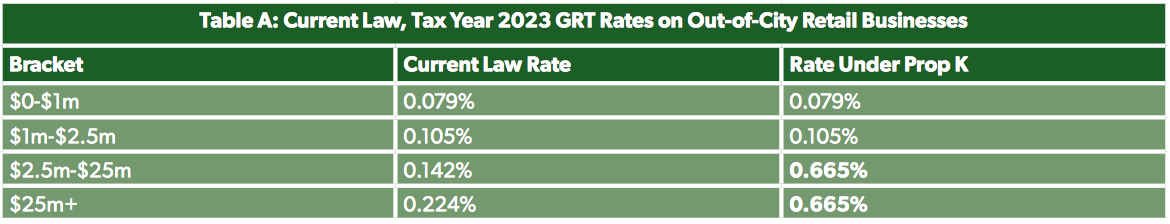

Under Proposition K, any business making over $2.5 million in revenue that ships goods to customers in San Francisco would have its taxable income above $2.5 million bumped into the bracket for businesses with over $25 million in revenue, beginning in tax year 2023. The rates for that $25 million bracket would also be increased, to the level paid by transportation and warehousing businesses.

For businesses with revenues in the $2.5 million to $25 million range, this would represent a substantial tax increase. An affected business with exactly $25 million in gross revenue in San Francisco would see its annual tax bill jump from about $34,000 to just under $150,000.

Businesses in this range may sound large, but many would be considered small businesses. Many e-retail businesses operate on small profit margins, and gross revenue numbers do not take into account all the costs that go into operating a business — the main reason that GRTs are frowned upon by tax policy experts.

Per California law, a small business is defined as a business with less than $15 million in annual revenue and fewer than 100 employees. According to San Francisco’s Tax and Treasurer’s office, more than 600 businesses in the Retail and Wholesale tax categories have over $2.5 million in annual revenue and less than $15 million. These businesses, likely nearly all small businesses under California law, would suddenly find themselves facing the tax rates of large businesses under Prop K. A business with $15 million in revenue in 2023 would see its tax bill increase from $20,000 to $85,500.

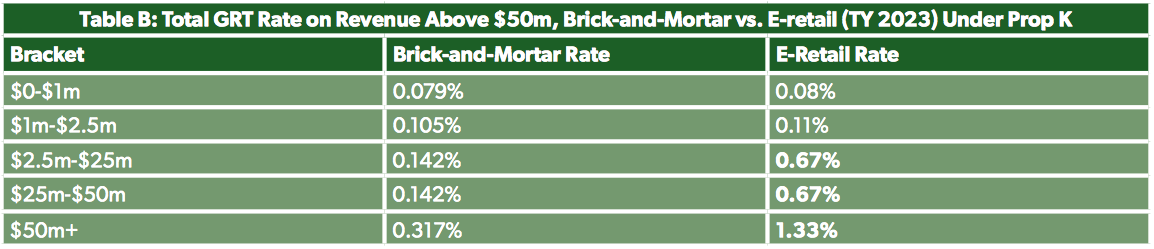

Prop K doesn’t spare larger businesses, either. Not only would large e-retail businesses face the same bracket hikes, they would also face an increase to the city’s additional Homelessness Gross Receipts Tax, applying to business revenue over $50 million. Rather than paying the previous Retail and Wholesale trade rate of 0.175 percent as brick-and-mortar businesses would, businesses delivering goods into the city of San Francisco would again pay a rate of 0.665 percent.

And while this measure is being billed as a tax on Amazon, the e-retail giant is ironically likely to be unaffected. Under the rules of San Francisco’s GRT, if a business derives more than 80 percent of its revenue in the city from a certain trade categorization, all of its income is taxed under that category. Since so much of Amazon’s local revenue comes from its Amazon Web Services business, it will likely be taxed entirely in the “Information” category — a categorization unaffected by Prop K’s tax increases.

More Than Just a Foolish Tax Increase

All of this is rather clearly a poorly-considered and structured tax hike targeting what is perceived to be a productive sector of the economy ripe for taxation. But it also faces several other administrative and legal pitfalls that are likely to cause both San Francisco and out-of-city businesses grief should Prop K move forward.

First and foremost, Prop K would represent an undue burden on interstate commerce, one that is likely to face challenges under the dormant commerce clause. The structure of the tax ensures that San Francisco-based businesses face significantly lower tax rates than businesses that sell into the city, as Tables A and B show, with no justification.

A main reason the United States has a Constitution rather than Articles of Confederation is to prevent sub-national bodies from attempting to fill their coffers with revenue from non-residents in order to offer their residents lower tax rates. Not only is this manifestly unfair, it is also bad for the country as a whole, as it unmoors the taxpayer from representation in the legislative body taxing them. Absent a federal government protecting taxpayers from states and localities trying to “import” revenue from each others’ citizens, interstate commerce suffers.

The burden created goes beyond just the rate increases themselves. Creating a separate tax rate for e-retail transactions requires small businesses to determine what is and isn’t taxable under the new rates, and track this in their accounting operations. Many likely will not have the capability to do so.

What’s more, San Francisco’s compliance burden increase does not take place in a vacuum. States and localities have been steadily increasing compliance burdens on businesses selling around the country for years now in an effort to glean more revenue from the digital economy, from economic nexus sales tax rules to expansions of income tax nexus to delivery fees. For small businesses trying to run their businesses and pay their taxes, it is death by a thousand cuts.

There’s another potential legal barrier as well. The federal Internet Tax Freedom Act (ITFA) prohibits states and localities from imposing discriminatory taxes on internet commerce. One such form of prohibited discriminatory taxation is defined under ITFA as taxes that are “not generally imposed and legally collectible at the same rate by such State or such political subdivision on transactions involving similar property, goods, services, or information accomplished through other means.”

Taxing e-retail transactions at rates that are several times higher than domestic brick-and-mortar businesses face appears to be a rather straightforward violation of this principle. Should Prop K be passed into law, it would likely face a strong challenge under ITFA. And for good reason — it is bad for the country if states and localities are smothering the baby in the crib by targeting the innovativeness of the digital economy for special taxes.

Lastly, while this measure will certainly harm small businesses selling into San Francisco and is structured to try to export the tax burden, it is likely to also hurt San Franciscans. Businesses selling into San Francisco would most likely respond by increasing prices or attaching surcharges to cover the added cost of doing business in San Francisco. Some may even decide that the cost of selling to San Francisco customers outweighs the benefit.

Conclusion

Responding to concern about the tax not applying to Amazon, Prop K’s backers have since suspended their campaign for the ballot measure and are seeking to remove it from the ballot. But they have also dismissed concerns about the impact on small businesses and, should they succeed in removing it from November’s ballot, will likely try again with a substantially similar proposal next November.

If San Francisco deems a UBI to be a policy priority, it should find a means to fund it that does not involve half-baked schemes to export the costs and import revenues. Not only is Prop K likely to create significant compliance and tax burdens on e-retail businesses for no reason, it will also send a message to businesses that San Francisco intends to take advantage of any business unwise enough to do business in the city.

The digital economy continues to be a tempting target for cities seeking “easy” revenue, but the consequences of cities forgetting that not every e-retail business is Amazon could be enormous. Legislators at every level of American government must do a better job remembering that the benefits of digital commerce can easily be taxed and regulated away if they are not careful.