(pdf)

Back in March, when the scope of the impending global health crisis associated with COVID-19 was becoming apparent, speed in forming a legislative response at the federal level was the name of the game. Americans were getting laid off in record numbers,[1] businesses were teetering on the brink, and the healthcare system was threatening to be overwhelmed. Legislation was needed, and quickly.

In response, Majority Leader McConnell cancelled the Senate’s planned recess and hammered out bipartisan legislation that included $1,200 payments to Americans with only limited means-testing,[2] expanded unemployment benefits, loans to businesses, funding for the healthcare system, and aid to states. Legislation was ready to go, with the Senate having — by Congress’s standards, at least — moved quickly.

That’s when Speaker Pelosi returned from the House’s recess to blow up the process.[3] Ignoring the Senate draft, Pelosi dropped her own economic relief legislation that addressed a litany of progressive pet issues[4] — but not so much the crisis caused by the coronavirus.

After further negotiations, Congress eventually passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, legislation that contained all the basic elements of the original Senate bill. But valuable days were lost in the meantime, days in which Americans struggling to buy groceries were not receiving their relief payments, businesses were unable to access loan funding to retain their employees, and hospitals were not able to receive badly needed funding.

The plan was formally introduced by House Appropriations Committee Chairwoman Nita Lowey (D-NY) as H.R. 6379, the Take Responsibility for Workers and Families Act. While the bill ultimately went nowhere, it’s worth looking at the contents of the bill that Speaker Pelosi felt was worth delaying aid to Americans struggling with a pandemic and a recession. What one finds is a series of proposals to expand the size of government — in areas that are only tangentially related to the circumstances presented by the coronavirus.

And despite the delays it cost, H.R. 6379 ultimately had very little impact on the final CARES Act, with at least $364 billion in proposed new spending not making it into the final relief legislation.

Budget Plus-Ups Galore

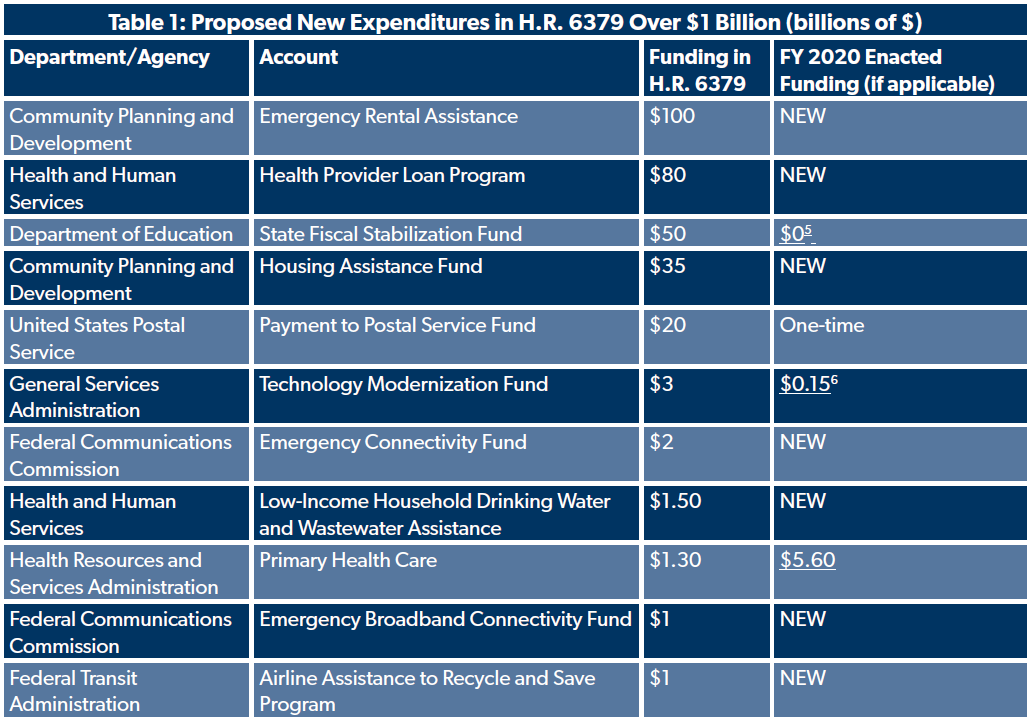

NTUF compared the proposed increases to the funding of various federal departments, agencies, and programs included in the House bill, finding that some would receive many times their annual appropriation. That in itself would hardly be unusual for targeted response legislation, except that many of the recipients of this largesse are not involved in healthcare or likely to assist with economic relief or recovery. Table 1 shows new expenditures of over $1 billion in the bill, many of which have little or nothing to do with the public health or economic consequences of COVID-19.

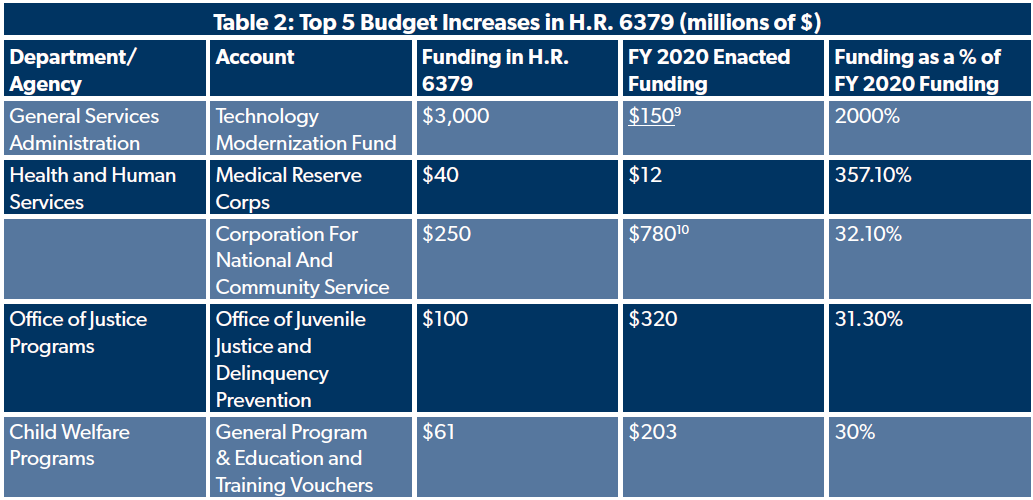

Some of the numbers are eye-popping. The House Bill, for example, included $25 billion in funding for the Federal Transit Administration’s Transit Administration Grants — nearly fifty times as much as the program’s $510 million FY 2020 appropriation.[7] Also included in the budget is a $3 billion appropriation for the General Services Administration’s Technology Modernization Fund. For context, the Technology Modernization Fund received an appropriation of just $150 million in FY 2020.[8]

Table 2 shows a selection of the five most significant budget increases proposed in the Pelosi draft that did not make it into the CARES Act.

In total, the House bill contained more than $300 billion in potential new spending that did not make it into the CARES Act. Much of this would have come from two new programs — a $100 billion appropriation for “Emergency Rental Assistance” and a $35 billion appropriation for a “Housing Assistance Fund.”

Some line items in the House bill represent little more than ideological food fights that have been carried into a new arena. For example, the bill contains $300 million each for the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) — nearly double the agencies’ $172 million and $175 million respective FY 2020 appropriations.[11] In past executive budgets, President Trump has proposed eliminating both the NEA and NEH,[12] proposals that incensed Democrats. Yet through the House bill, Pelosi chose to take up this grievance as part of crisis response negotiations.

The House bill also included $20 billion in aid to the Postal Service, an organization that struggles to remain financially viable. The United States Postal Service has been losing money, despite federal funding, since FY 2007. Though many, including our colleagues at NTU,[13] have called for reform, the House bill would have simply thrown more money at the problem.

Many more such items unrelated to the pandemic litter the legislation. The House bill included $1 billion for sustainable fuel development and an airline “cash for clunkers” boondoggle. It also included a further $250 million in funding for AmeriCorps, a program that is supposed to be phased out by 2021, and $100 million in funding for NASA.

Another significant item on the Democratic wish list that made it into the House coronavirus response bill was a bailout for the federal multiemployer pension insurance program, which faces a $65 billion shortfall.[14] NTUF has previously written about how the multiemployer pension bailout plan does little to address underlying problems with the program that led to its financial woes.[15] Rather than shoring up the under-funded pensions with real reforms, the Democratic plan would merely delay insolvency, leaving taxpayers exposed to massive liabilities. Though such a bailout plan is unlikely to be effective, the Congressional Budget Office estimates it would cost taxpayers nearly $50 billion over the next ten years.[16]

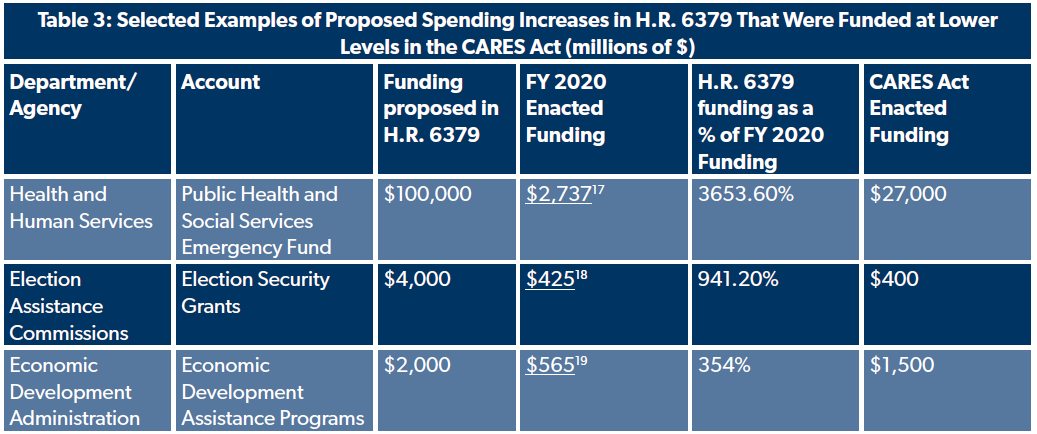

Some items in Pelosi’s legislation did make it into the final CARES Act, but not nearly at the funding levels laid out in H.R. 6379. Table 3 includes three proposed funding increases proposed in the House bill that made it into the CARES Act but at a lower funding level.

Pelosi’s legislation also would have included $50 billion in additional funding to states. Congress included $150 billion in funding to states as part of the CARES Act, but state governors are demanding a staggering $500 billion from Congress.[20] Pelosi brought the issue up again when Congress was scrambling to replenish the depleted accounts of the CARES Act’s small business loan program, the Paycheck Protection Program.[21]

Tax Provisions

In addition to including dozens of plus-ups for agency budgets, the Pelosi bill also contained several tax provisions that have since become the subject of controversy. Most notably, it included a significant expansion in the allowable use of “net operating losses” (NOLs). When a company’s deductions exceed its taxable income in a year, an NOL is generated that can be carried forward to reduce future tax liabilities. This helps businesses smooth profits and losses across tax years to ensure they’re taxed on their economic income and not an accounting byproduct, since profitability doesn’t always align perfectly with a tax or calendar year.

While the Pelosi draft disallowed expanded use of NOLs for companies that engaged in significant stock buybacks, the language was otherwise broadly similar to what eventually became law in the CARES Act. This is notable because the expansion of NOLs has subsequently become a controversial subject, with some detractors decrying them as “handouts” to the wealthy.[22] While that rhetoric is flawed,[23] to say the least, it bears repeating that House Democratic leaders included a similar expansion in their own draft of coronavirus response legislation, raising questions about whether current opposition is genuine or merely opportunistic.

Regulatory Provisions

Pelosi's draft would have also imposed regulatory policies entirely unrelated to the current crisis. Airlines are among the worst hit industries in the wake of the pandemic, with widespread international travel restrictions and guidelines for maintaining social distancing, but the bill would have required any air carriers that receive assistance under the bill to fully offset their carbon emissions, to include labor union representation on their board of directors, and to remain neutral for the next five years in any attempts to organize union campaigns. These policies would have the likely effect of raising ticket prices for consumers due to higher labor costs and new emissions offset expenses, all in service of checking off items that were on the progressive wish list long before COVID-19 existed. This would only strengthen the economic headwinds against the airline industry.

While businesses are struggling to stay afloat, the Pelosi bill would also have taken advantage of the situation to impose expansive new diversity reporting requirements on companies receiving COVID-19 federal aid. Businesses would be mandated to report on their employees' "gender, race, and ethnic identity (and to the extent possible, results disaggregated by ethnic group)" and also on the diversity of their suppliers, including the "number and dollar value invested with minority- and women-owned suppliers (and to the extent possible, results disaggregated by ethnic group), including professional services (legal and consulting) and asset managers, and deposits and other accounts with minority depository institutions, as compared to all vendor investments." The mandates would also demand information on salaries by ethnic group and among men and women, reports on the gender and race of board members, and on the number of staff dedicated to "diversity and inclusion initiatives."

Whatever merits these new regulatory requirements might or might not have, they cannot be said to be aimed squarely at the public health crisis associated with COVID-19. Instead, they are classic examples of exploiting a crisis to advance the goals of a much larger, more powerful, and more expensive federal government.

Round Two - The HEROES Act

On May 12, Speaker Pelosi released new legislation that contains even more significant funding increases, including over $1 trillion in aid to state and local governments alone. In total, the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act includes at least $3.5 trillion in spending increases.

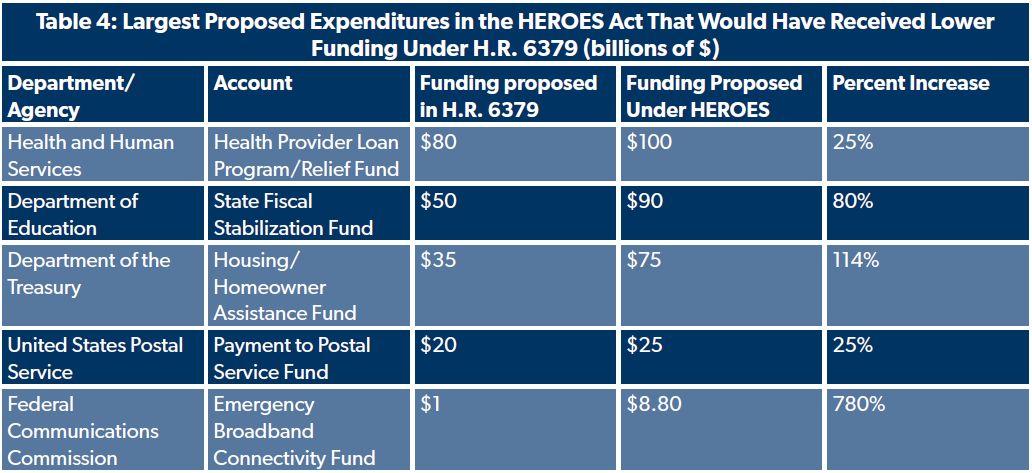

Some of the proposed expenditures in the HEROES Act are directly carried over from H.R. 6379, such as the proposal for $100 billion in emergency rental assistance. As Table 4 shows, however, most funding proposals that are taken from H.R. 6379 are funded at even higher levels in the HEROES Act.

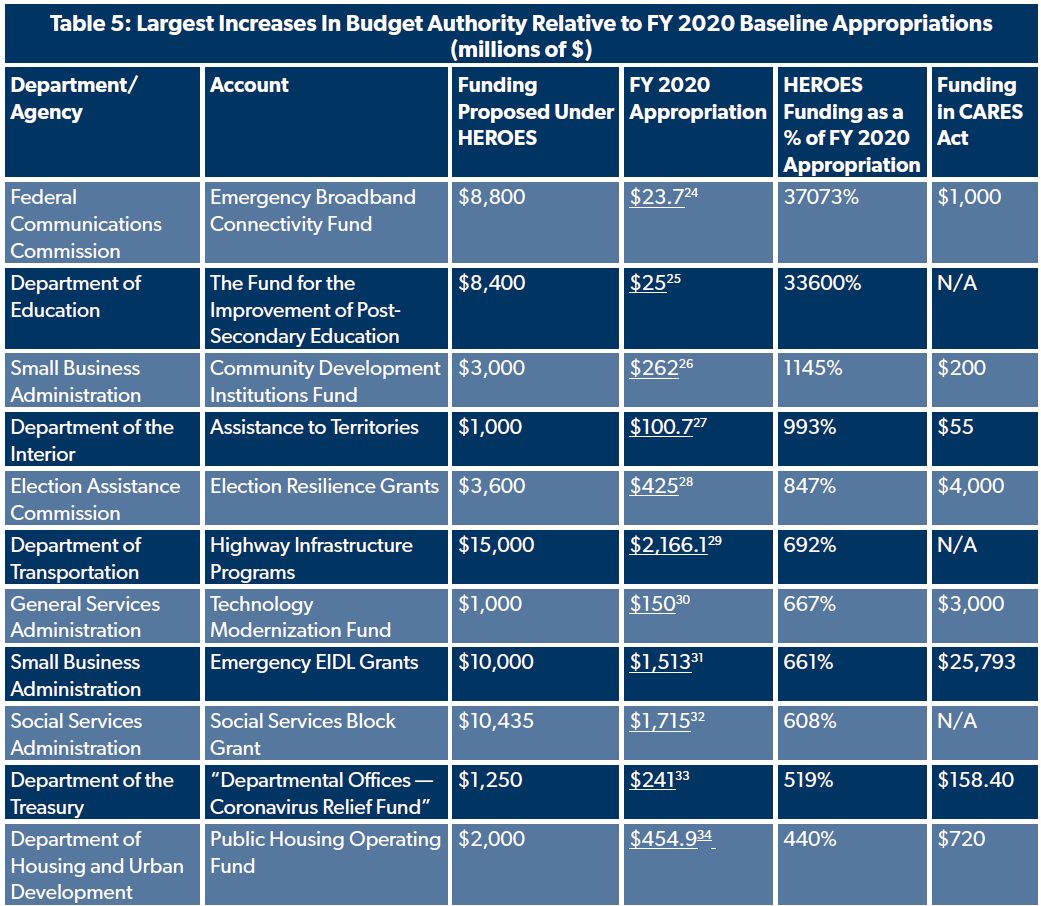

And just like with H.R. 6379, the HEROES Act includes several proposed expenditures that represent massive increases relative to baseline appropriations. Table 5 lists the ten most significant program funding increases as compared to their FY 2020 budget budget appropriations.

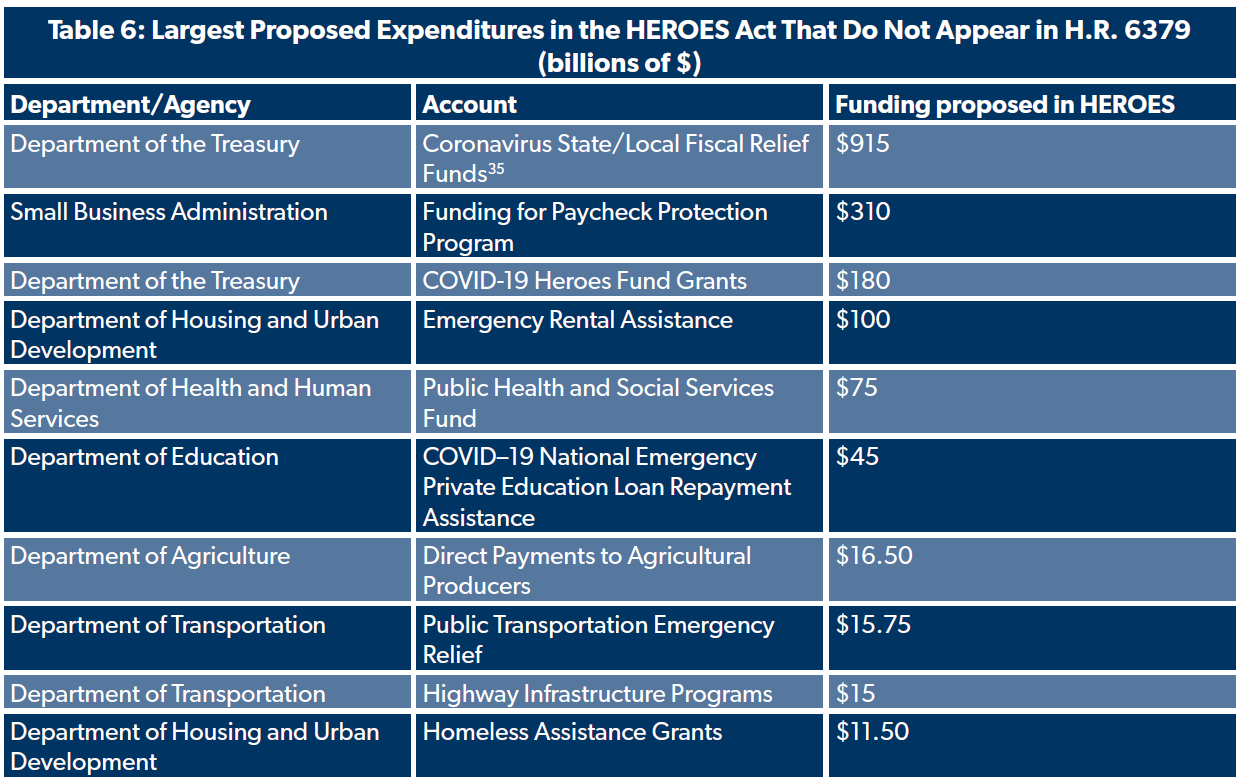

Yet while many proposed expenditures in HEROES are boosts to funding amounts proposed in H.R. 6379, many more are unique to the HEROES Act. Table 6 lays out the ten most significant spending proposals in the HEROES Act in absolute dollars.

While these funding proposals make up a significant amount of cash on their own, the HEROES Act is so flush with extravagant spending proposals that many proposals outside the “top 10” proposals still come with price tags of several billions of dollars. Notable examples include a $10 billion appropriation increase to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), a $5 billion expenditure for Community Development Block Grants, and $4 billion for tenant-based rental assistance.

Conclusion

While Congress should be thinking seriously about other actions it could take to reduce the negative impacts of the pandemic, those efforts should be targeted at the health and economic effects Americans are facing rather than being used as an excuse to fatten bureaucratic budgets and advance controversial policy schemes.

[1] Davis, William. “More Than Three Million Americans File For Unemployment, Shattering Previous Record.” The Daily Caller, March 26, 2020, https://dailycaller.com/2020/03/26/three-million-jobs-lost-unemployment-coronavirus/.

[2] Generally speaking, means-testing is a good way to prevent waste of taxpayer dollars. In this case, however, extensive means-testing would have significantly slowed down the process of getting economic relief payments out the door and into the hands of Americans that needed them;

Levine, Marianne and Desiderio, Andrew. “McConnell delays Senate recess amid coronavirus crisis and FISA deadline.” Politico, March 12, 2020, https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/12/mitch-mcconnell-delays-senate-recess-127344.

[3] Re, Gregg. “Pelosi, returning from recess, announces House Dems will have their own coronavirus response bill.” Fox News, March 22, 2020, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/pelosi-house-democrats-coronavirus-response-bill-recess.

[4] Wilford, Andrew. “The COVID Relief Bill Passed, But Democrats’ Delays Cost Americans Everywhere.” The Daily Caller, March 31, 2020, https://dailycaller.com/2020/03/31/wilford-the-covid-relief-bill-passed-but-democrats-delays-cost-americans-everywhere/.

[5] Department of Education, “State Fiscal Stabilization Fund.” Accessed May 11, 2020 at https://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/leg/recovery/factsheet/stabilization-fund.html.

[6] General Services Administration, “FY 2021 Congressional Justification.” Accessed May 11, 2020 at https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/GSA_FY2021_Congressional_Justification.pdf.

[7] In fairness, it’s possible the Speaker simply got tired of waiting for Infrastructure Week to happen.

Department of Transportation, “FY 2021 Budget Highlights.” Accessed May 11, 2020 at https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2020-02/BudgetHightlightFeb2021.pdf.

[8] General Services Administration, “FY 2021 Congressional Justification.” Accessed May 11, 2020 at https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/GSA_FY2021_Congressional_Justification.pdf.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Meant to be cut entirely by FY 2021.

[11] National Endowment for the Arts, “Appropriations Request for Fiscal Year 2021.” Accessed May 11, 2020 at https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/NEA-FY21-Appropriations-Request.pdf; Appendix, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2021. Accessed May 11, 2020 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/oia_fy21.pdf.

[12] Krieghbaum, Andrew. “Trump Seeks to Ax Humanities Endowment,” Inside Higher Ed, March 19, 2019, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/03/19/trump-proposes-axing-nea-neh.

[13] Sepp, Pete. “Another Quarterly Postal Loss, Another Taxpayer Headache,” National Taxpayers Union, August 9, 2019, https://www.ntu.org/publications/detail/another-quarterly-postal-loss-another-taxpayer-headache.

[14] Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, “Annual Report 2019.” Accessed on May 11, 2020 at https://www.pbgc.gov/sites/default/files/pbgc-fy-2019-annual-report.pdf.

[15] Wilford, Andrew. “Multiemployer Pension Plan Bailout Fails to Address Structural Problems,” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, July 22, 2019, https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/multiemployer-pension-plan-bailout-fails-to-address-structural-problems.

[16] Congressional Budget Office, “Cost Estimate for H.R. 397, Rehabilitation for Multiemployer Pensions Act of 2019.” Accessed on May 11, 2020 at https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-07/hr397_2.pdf.

[17] Department of Health and Human Services, “FY 2021 Budget in Brief.” Accessed on May 11, 2020 at https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2021-budget-in-brief.pdf.

[18] Appendix, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2021. Accessed May 11, 2020 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/oia_fy21.pdf.

[19] Appendix, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2021. Accessed May 11, 2020 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/com_fy21.pdf.

[20] Office of Governor Larry Hogan, “Nation’s Governors Urge Federal Leaders to Provide Immediate Fiscal Relief for States.” Accessed on May 11, 2020 at https://governor.maryland.gov/2020/04/11/nations-governors-urge-federal-leaders-to-provide-immediate-fiscal-relief-for-states/.

[21] Wilford, Andrew. “Governors Demand Massive $500 Billion Payday From Congress,” The Daily Caller, April 23, 2020, https://dailycaller.com/2020/04/23/wilford-governors-demand-massive-500-billion-payday-from-congress/.

[22] Drucker, Jesse. “Bonanza for Rich Real Estate Investors, Tucked Into Stimulus Package,” New York Times, March 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/26/business/coronavirus-real-estate-investors-stimulus.html.

[23] Kaeding, Nicole. “Net Operating Losses Aren’t Handouts,” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, April 14, 2020, https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/net-operating-losses-arent-handouts.

[24] Department of Commerce, “FY 2021 Budget as Presented to Congress.” Accessed May 27, 2020 at https://www.commerce.gov/sites/default/files/2020-02/fy2021_ntia_congressional_budget_justification.pdf.

[25] Office of Management and the Budget, “A Budget For America’s Future.” Accessed May 27, 2020 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/msar_fy21.pdf.

[26] Ibid.

[27] H.J.Res.31 - Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2019, February 15, 2019, https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ6/PLAW-116publ6.pdf.

[28] Appendix, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2021. Accessed May 27, 2020 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/oia_fy21.pdf.

[29] House Amendment to the Senate Amendment to H.R. 1865, December 16, 2019, https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/H1865PLT_44.PDF.

[30] General Services Administration, “FY 2021 Congressional Justification.” Accessed May 27, 2020 at https://www.gsa.gov/cdnstatic/GSA_FY2021_Congressional_Justification.pdf.

[31] Appendix, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2021. Accessed May 27, 2020 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/sba_fy21.pdf.

[32] Appendix, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2021. Accessed May 27, 2020 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/hhs_fy21.pdf.

[33] Department of the Treasury, “FY 2021 Budget In Brief.” Accessed May 27, 2020 at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/266/FY-2021-BIB.pdf.

[34] Department of Housing and Urban Development, “ FY 2021 Budget In Brief.” Accessed May 27, 2020 at https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/CFO/documents/BudgetinBrief_2020-02_06_Online.pdf.

[35] Separate line-items exist for the State Fiscal Relief Fund and the Local Fiscal Relief Fund. They are combined here for convenience.