By Demian Brady

(pdf)

As taxpayers have begun to file after the one-year anniversary of the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, it’s an opportune time to reflect on the tax relief it brought. Lower tax rates across-the-board increased take home pay for workers. And thanks to the increased standard deduction, an estimated 31 million filers will no longer need to itemize their taxes, reducing the compliance burden by 248 million hours. With a reduced corporate tax rate that has made the U.S. more competitive, the TCJA also helped spur a booming economy that is generating record levels of tax receipts.

For historical information:

- Analysis of Who Pays Income Taxes TY2015

- Analysis of Who Pays Income Taxes TY2014

- Who Pays Income Taxes TY2013

- Who Doesn't Pay Income Taxes?

Despite the achievement of the TCJA, many politicians remain opposed to the tax cuts. And they employ worn out class warfare rhetoric to inaccurately disparage the law or even any attempt to reduce income taxes. Nancy Pelosi, and several others in her party, have slammed the tax cuts as a giveaway to the rich and complain that the wealthy are not paying their “fair share.”

First of all, reducing taxes allows people to keep more of what they created and earned – that’s not a giveaway. Second, Pelosi and her colleagues neglect to take into account the fact that under the progressive tax code, the top income earners pay an outsized share of income taxes. And the biggest unreported fact about TCJA is that it will increase the progressivity of the tax system.

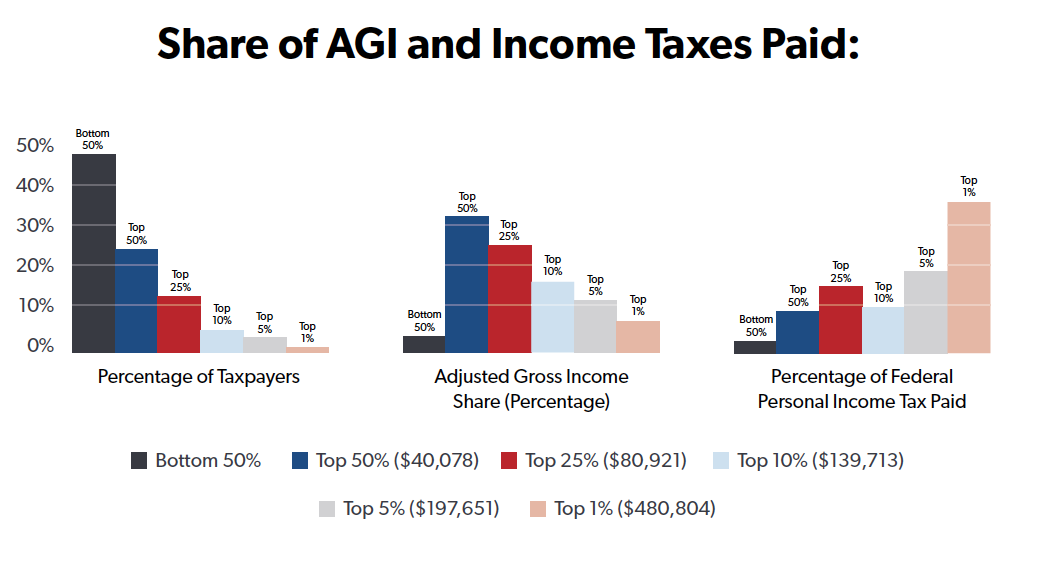

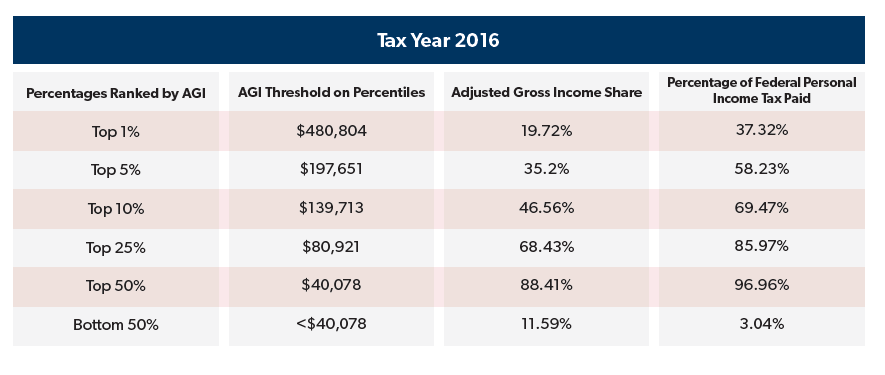

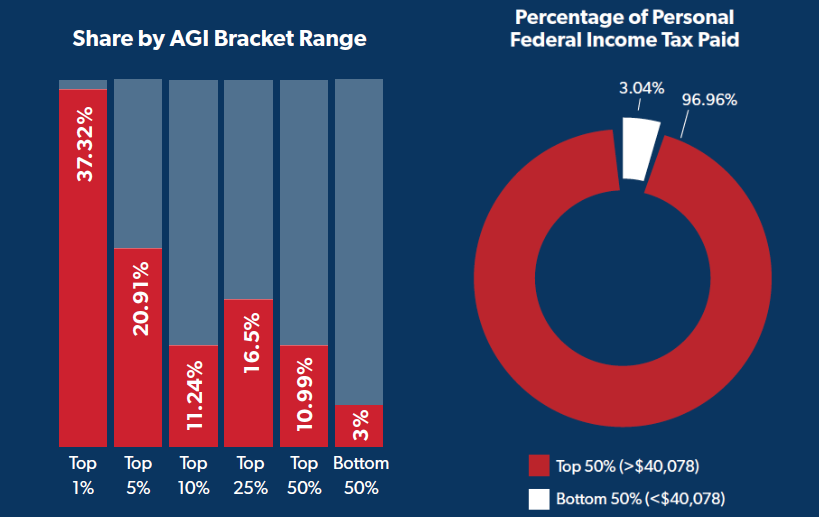

The IRS has recently released an analysis of the distribution of the income tax burden for Tax Year 2016. The new data shows that the top one percent of income earners bear the burden of 37 percent of all income taxes. This is nearly twice as much as their share of income (19.7 percent). The top 25 percent of earners shoulder nearly 86 percent of the income tax load. Combined, the top 50 percent of earners are responsible for 97 percent income taxes collected. The other half of filers pay just 3 percent of all income taxes.

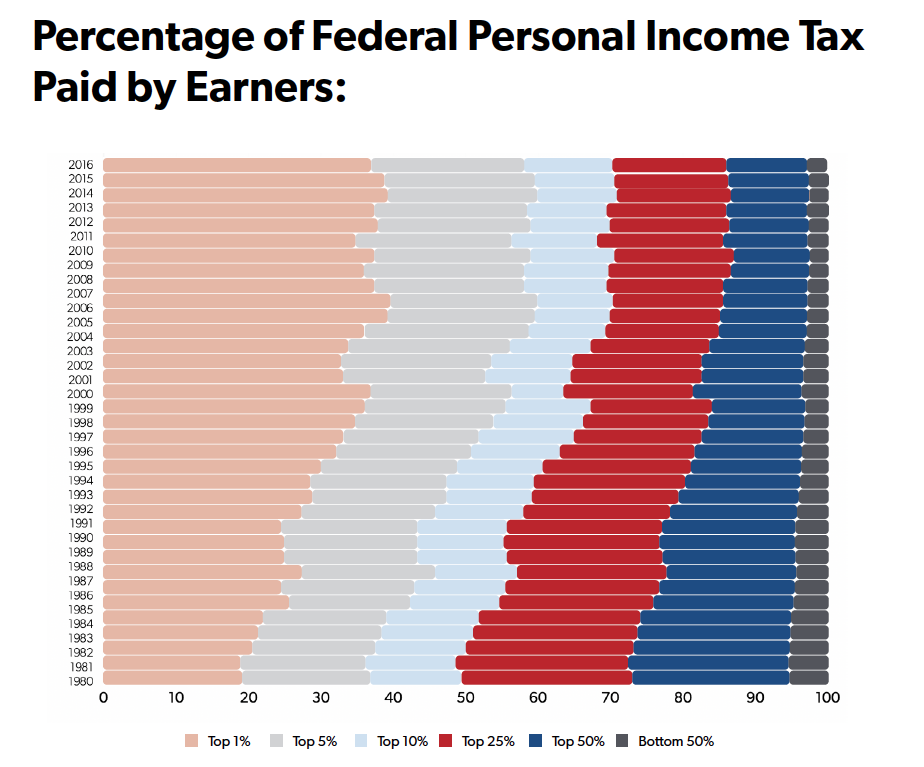

NTUF has compiled historical data tracking the distribution of the federal income tax burden back to 1980. In that year, the top one percent of filers’ income tax share was 19 percent – that’s nearly half of what it is now. On the other side of the spectrum, the bottom fifty percent’s share has been cut from 7 percent to 3 percent over the past 38 years. And this happened despite the top marginal income tax rate falling from 70 percent in 1980 to 39.6 percent by 2016.

The trends are clear: the code has become increasingly progressive, and when people are allowed to keep more of their own money, they prosper, move up the economic ladder, and pay a bigger part of the income tax bill for those who aren’t.

The tax code provides net assistance to many filers working their way up the economic ladder. A Congressional Budget Office report on shows that households in the lowest income quintiles actually have negative tax liabilities. This means that they are recipients of refundable tax credits which can be claimed above and beyond any net income taxes owed. For example, almost 26 million households received the Earned Income Tax Credit in 2016. Beyond reducing many filers’ tax obligation, this refundable credit resulted in outlays totaling $61 billion.

After accounting for low-income levels and various tax credits, 33.4 percent of returns in Tax Year 2016 paid no income tax, up significantly from 21.3 percent in 1980.

While it’s true that the benefits of the tax cuts enacted in the TCJA went to the top income earners who pay most income taxes, it is also expected that the TCJA will increase the progressivity of the code. The combination of the near-doubling of the standard deduction and the expanded child credit will increase the number of filers with zero income tax liability. The Tax Policy Center estimated that an additional 2.4 percent of tax units will owe nothing. David Splinter of the Joint Committee on Taxation simultaneously projected that the TCJA will increase the figure by 2.5 percent.

Splinter also finds that most of the increase in the number of filers with no liability over the past decades has occurred because of changes in tax policy, more so than the health of the economy. Using an econometric index, he calculates that the code has become much more progressive since 1985 – due to exclusions and increases in refundable credits – and that the TCJA will further increase its progressivity.

The lopsided income tax burden carried by the top income earners raises the question: just what is a “fair” level of taxation? Until recently, those who complained most loudly that the rich are not paying their fair share generally refrained from specifying what would be an appropriate amount. In July 2018, Senator Elizabeth Warren agreed that a 90 percent rate “sounds pretty shockingly high,” but was unwilling to state just what tax rate she would support. This year the new left has ratcheted up calls for higher taxes with some specifics. Newly-elected Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez led the charge with a 70 percent marginal rate on incomes above $10 million. Warren responded with a proposal for a 2 percent wealth tax on households with a net worth of $50 million, and a 3 percent rate on households with over $1 billion in wealth. It's worth noting that while these proposals would further increase the progressivity of the tax system – and the wealth tax in particular would impose significant additional administrative complexities and compliance burdens, and may not be constitutional – they would also only pay for a fraction of new spending programs, including Medicare for All, also being pitched by the high tax advocates.

And just who are the “rich” that are allegedly not paying their “fair share”? The minimum threshold to be counted among the wealthiest tenth of taxpayers is just under $140,000, and the top quarter’s threshold starts at just under $81,000. The latter is comparable to the median income that year in several large metropolitan areas. Many homeowners who think of themselves as middle-class may be surprised to learn that the tax code classifies them among the rich.

As pundits and politicians complain about “tax fairness” taxpayers should press them to specify what would be fair. They should also be reminded that with lower taxes, people keep more of what they earned and spend or save their dollars more productively than Washington, DC. The lesson of tax reform efforts from the Kennedy-Johnson tax cuts through the Reagan and Bush era is that tax cuts stimulate productivity and job growth. Increasing the tax rates could reverse the economic expansion. That wouldn’t just be unfair, it would be unwise.