Expensing is the “killer app” of tax reform, a subtle feature that promises to unlock tremendous growth.

The bottom line? Full expensing...

|

Despite this fantastic potential, one of the most significant sticking points in the tax reform debate is the issue of full expensing for business investments. While it can, understandably, be difficult to get excited about how the federal government taxes business investments, full expensing is one of the best and most efficient methods of corporate tax reform currently in front of Congress.[1]

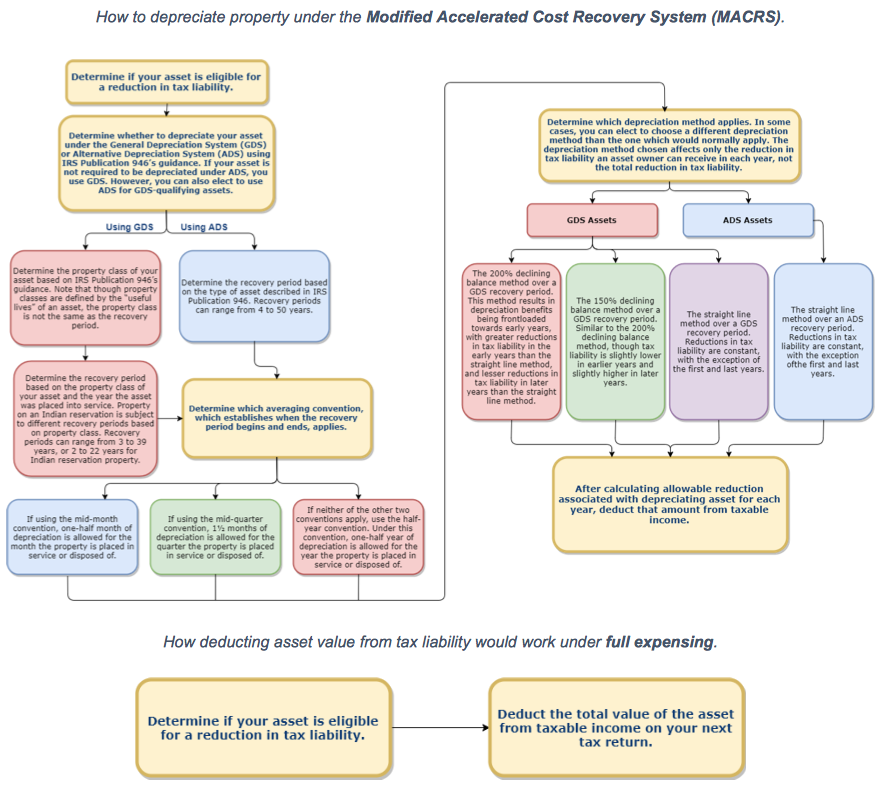

Full expensing would allow businesses to deduct the full value of investments from their tax liability the year of the investment. In doing so, it would reduce the staggering complexity of tax treatment for business assets and encourage increased investment that can fuel economic growth. Concerns about the policy – that it must “compete” with steeper rate reductions, or that it is likely to have substantial effects on our long-term deficit – are misguided.

How Does Asset Depreciation Work?

Though it provides the greatest incentives for economic investment, full expensing is not the statutory method of calculating tax liabilities related to investment.[2] The current method is known as asset depreciation, which allows businesses to deduct a certain amount from their taxes over the useful life of an asset. Assets are subject to depreciation under the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS), a bureaucratic nightmare that imposes a substantial compliance burden.[3] Since businesses spend over 448 million hours annually complying with depreciation regimes,[4] the Tax Foundation estimates that compliance costs can reach $23 billion annually.[5]

Under MACRS, the initial costs of assets can generally be recovered over anywhere from a three-year period to a 50-year period. Assets are assigned a “property class,” ostensibly determined by its “useful life.” In practice, the inefficient nature of the system means that this is often not the case.[6]

The majority of assets use the General Depreciation System (GDS), though a small percentage fall under the Alternative Depreciation System (ADS).[7] Determining which depreciation system an asset qualifies for can be difficult under the best advice, and the Internal Revenue Service’s (IRS) guidance on which of these systems to utilize seems designed to confuse people even further. In Publication 946, “How to Depreciate Property,” the IRS states: “You generally must use GDS unless you are specifically required by law to use ADS or you elect to use ADS.”[8] The bureaucrats of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 would be proud.

Under the terms of the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act of 2015, corporations are allowed to deduct 50 percent of the initial value of an investment and then depreciate the remaining value over the lifetime of the product. This is known as bonus depreciation, and represents a form of compromise between a depreciation system and one that allows full and immediate expensing. The PATH Act contains a phase-out period for bonus depreciation, where assets that go into use in 2018 are subject to a 40 percent initial deduction, and assets going into use during 2019 are subject to a 30 percent initial deduction. Without further legislation, most assets would not be eligible for any form of bonus depreciation following 2019.[9]

How Would a Switch to Full Expensing Benefit the Economy?

One major benefit of full expensing is that it is less complex. With full expensing, businesses deduct the entire cost of an investment up front, rather than spreading it out over a complicated schedule. The benefits of doing away with a complex depreciation system can go well beyond reducing compliance costs. Businesses – especially smaller companies – may not take advantage of the full deduction for which they are eligible due to the difficulty associated with complying with depreciation rules.

“Supporters of tax reform should not let smarter policy on expensing compete with smarter policy on corporate tax rates. They are, to appropriate an old advertising slogan, two great tastes that taste great together.”

Businesses may even reduce the size and number of investments they make to limit their exposure to penalties for misinterpreting the system. Rebecca Boenigk, the CEO of a Texas manufacturing company who testified before the House Ways and Means Committee in July, is just one example of a small business owner who has limited the size of her company’s investments because of asset depreciation rules. As she told The Atlantic, “We can just make the best business decision we can make and hope we don’t get penalized too much for it … [b]ut if we knew that we had full expensing, the building would probably be bigger.”[10]

Another benefit of full expensing is that businesses value money in their hands today rather than tomorrow. Deductions allowable to a business today free up resources that can be invested to generate a return; deductions provided over a longer period of years have an opportunity cost of lost interest earnings and growth. Therefore, a system of depreciation schedules provides less value than full expensing. The Tax Foundation estimates that, in 2012, businesses were able to deduct only 87 percent of the value of their investments. Without bonus depreciation, businesses would only have been able to deduct 83 percent.[11]

Full expensing ensures that businesses can write off the entire value of their investments in capital assets and equipment on their taxes. With this assurance, businesses can make purchasing decisions on a rational basis rather than having to consider and calculate the complicated MACRS tax consequences, as every dollar they put towards new investments and business growth will be deducted from their tax liabilities with limited hassle.[12]

Full expensing also targets the arbitrary nature of the depreciation system. A natural byproduct of the IRS taking on the herculean task of micro-managing the “useful lives” of assets is that fundamentally different assets can be grouped together under the same property class. Thus, the incentives for business investments weigh artificially in favor of assets with shorter recovery periods, rather than investments that will provide the greatest overall value simply as a result of their favorable tax treatment.[13]

Economists and center-right policy organizations are in broad agreement that full expensing would provide a significant boost to economic growth. In February, NTU helped lead a coalition of 29 other organizations urging Congress to adopt full expensing for business investments.[14] Other organizations that signed on to the letter include a “who’s who” of conservative groups: Americans for Tax Reform, Heritage Action for America, FreedomWorks, Citizens Against Government Waste, and many others.

So, Full Expensing Sounds Great. What’s the Problem?

Full expensing has generally run into political, rather than ideological, opposition. It would have the effect of reducing revenues somewhat in the short term by allowing businesses to write off investments immediately. Policymakers who otherwise support tax reform but who are determined to limit its impact on the short-term deficit have raised concerns that including full expensing could result in a less significant reduction in the corporate tax rate.

Additionally, while full expensing promises significant economy-wide benefits, some industries see rate reduction as a higher priority. Several business coalitions have come out against expensing, seeing it as a policy that competes with steeper rate reductions or other goals.[15] In this view, revenue reductions are essentially a “zero-sum” game in which one dollar devoted to expensing means one dollar that cannot go toward lowering the rate.

Supporters of tax reform should not let smarter policy on expensing compete with smarter policy on corporate tax rates. They are, to appropriate an old advertising slogan, two great tastes that taste great together. Both policies reduce disincentives for investment on the margin, making it more likely that businesses will expand and hire. Deficit impacts they have can be offset by eliminating distorting credits and deductions, or by reducing expenditures.

One of the great lessons of the 1986 tax reform is that an otherwise excellent package was hampered by actually lengthening depreciation schedules in ways that reduced the growth that was unleashed by that landmark legislation.[16] This is because rate reductions offer relatively fewer economic benefits for a given revenue impact than full expensing. Tax Foundation compared two policies with identical impacts on revenue when fully phased in, a 6.75 percent cut to the corporate tax rate and full expensing for corporate investment. The result was that full expensing provided more than twice as much GDP growth over the long run.[17]

The reason for this stark difference is simple: while increased corporate profits from slashing the corporate tax rate can be spent by the benefiting corporations on anything, full expensing only benefits corporations when they invest in assets. This ensures that any tax revenue that the federal government forgoes by instituting a full expensing deduction goes directly towards investment and economic growth.

Similarly, Congressional budget hawks may be misled by any Congressional Budget Office (CBO) score of a tax reform package that includes full expensing. Because CBO uses a ten-year scoring window, proposals with a front-loaded cost often appear to do more to reduce revenue than is the case after getting past the initial transition period. As noted earlier, under current law, deductions are currently scheduled to take place over 3-, 5-, 7-, 10, 15-, and 20-year (or even longer) periods. Full expensing transitions tax deductions which were originally slated to take place over the long term into immediate tax deductions. Thus, under CBO’s scoring models, a pro-growth policy with limited revenue impact over the long term appears to have significant negative revenue impact over the short term.

Full expensing represents a surefire way to grow the economy. The real “competition” in tax reform should not be between two good policies (like expensing and rate reductions), but between good policies and bad policies (like distorting credits and deductions that add complexity). Congress should move past political food fights and get behind a policy that boosts economic growth, while also decreasing the deficit over the long run.

About this Issue Brief

This is the second release in NTUF’s “What’s the Deal with Tax Reform?” series, designed to provide non-technical explanations of highly technical tax policy issue.

About the Authors

Andrew Wilford is Associate Policy Analyst at the National Taxpayers Union Foundation, the research and educational affiliate of National Taxpayers Union.

Andrew Moylan is NTUF’s Executive Vice President.

Notes

[1] Pomerleau, Kyle, Why Full Expensing Encourages More Investment than A Corporate Rate Cut, Tax Foundation, May 3, 2017. https://taxfoundation.org/full-expensing-corporate-rate-investment/

[2] Michel, Adam N., Full Expensing Will Create Jobs and Economic Growth, Economics21, January 29, 2015. https://economics21.org/html/full-expensing-will-create-jobs-and-economic-growth-1229.html

[3] Fichtner, Jason J. and Feldman, Jacob M., The Hidden Cost of Federal Tax Policy, Mercatus Center, 2015. https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/fichtner_hidden_cost_ch5_web.pdf

[4] Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, Office of Management and Budget, Compliance Burden of Form 4562 - Depreciation and Amortization, May 2014. https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewICR?ref_nbr=201312-1545-029

[5] Hodge, Scott A., An Open Letter to Chairman Peter Roskam on Full Expensing, Tax Foundation, July 18, 2017. https://taxfoundation.org/open-letter-chairman-peter-roskam-full-expensing/

[6] Olson, John, Tax System’s Reliance on Economic Depreciation Hinders Growth, Tax Foundation, August 11, 2016. https://taxfoundation.org/tax-system-s-reliance-economic-depreciation-hinders-growth/

[7] Department of the Treasury, Report to The Congress on Depreciation Recovery Periods and Methods, July 2000. https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/Report-Depreciation-Recovery-Periods-2000.pdf

[8] Internal Revenue Service, Publication 946, How to Depreciate Property, 2016. https://www.irs.gov/publications/p946/ch04.html

[9] Puhl, Jacob, Bonus Depreciation: The PATH Act and Beyond, The Tax Advisor, March 1, 2017. https://www.thetaxadviser.com/issues/2017/mar/bonus-depreciation-path-act-beyond.html

[10] Berman, Russell, The Tax Break Dividing the Republican Party, The Atlantic, August 17, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/08/tax-reform-gop-full-expensing/537114/

[11] Greenberg, Scott, Cost Recovery for New Corporate Investments in 2012, Tax Foundation, January 21, 2016. https://taxfoundation.org/cost-recovery-new-corporate-investments-2012

[12] Michel, Adam and Furth, Salim, For Pro-Growth Tax Reform, Expensing Should Be the Focus, The Heritage Foundation, August 2, 2017. https://www.heritage.org/taxes/report/pro-growth-tax-reform-expensing-should-be-the-focus

[13] Norquist, Grover et. al., Coalition Letter in Support of Full Business Expensing and Advertising Deduction, February 22, 2017. https://www.theamericanconsumer.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Coalition-letter-in-support-of-full-business-expensing-and-advertising-deduction.pdf

[14] National Taxpayers Union, NTU Joins Free-Market Coalition Urging Congress to Pass Tax Reform, February 6, 2017. https://www.ntu.org/governmentbytes/detail/ntu-joins-free-market-coalition-urging-congress-to-pass-tax-reform

[15] Mui, Ylan, One Tax Break Could Save Companies $2 trillion, but They Don’t Want It, CNBC, September 19, 2017. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/19/major-companies-are-taking-a-pass-on-this-2-trillion-tax-break.html

[16] Ellis, Ryan, Low Rates Shouldn’t Compete with Full Business Expensing in Tax Reform, Forbes, September 18, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanellis/2017/09/18/low-rates-shouldnt-compete-with-full-business-expensing-in-tax-reform/

[17] Pomerleau, Kyle, Why Full Expensing Encourages More Investment than A Corporate Rate Cut, Tax Foundation, May 3, 2017. https://taxfoundation.org/full-expensing-corporate-rate-investment/