(pdf)

Over the past couple of years, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has released a decade’s worth of reports on the size of the “tax gap,” or the theoretical gap between the revenue the IRS takes in and amount of revenue the IRS believes it is owed. The IRS’s 2021 tax gap estimate of $625 billion has grown nearly $250 billion from the $381 billion estimate a decade ago.

While the latest report, covering tax years 2020 and 2021, appears at first glance to reveal worrisome increases in uncollected tax revenue, in truth it shows little more than business as usual at the IRS. The increase is not because taxpayers have become more dishonest; the increase in the estimated size of the tax gap is based primarily on increased levels of economic activity.

Crucially, it’s important to note just how theoretical these estimates are. The estimated size of the tax gap is just that — an estimate, and one with a high degree of uncertainty at that. Not only is the “tax gap” really just an amalgamation of many individual and distinct “tax gaps” for different sections of the tax code and economy, there are areas that the IRS’s “tax gap” estimate does not even attempt to measure. In short, while $625 billion is a clean number, it has a margin of error in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Particularly as the new $625 billion number makes its way into debates over enforcement resources for the IRS, policymakers should be aware of the figure’s limitations — as well as how much of the “tax gap” can realistically be closed.

Is the Tax Gap Becoming More of a Problem?

First and foremost, it should be noted that media outlets, and even the IRS itself, tend to highlight the $688 billion “gross tax gap,” rather than the $625 billion “net tax gap.” But there is little reason to focus on the “gross tax gap,” as the “net tax gap” figure is the one that takes into account late payments and enforcement efforts. What’s relevant to policymakers is tax revenue that is not being paid by taxpayers, not tax revenue that isn’t being remitted to the federal government on a fully voluntary basis.

Of course, by any metric, $625 billion is still a large sum of money. However, in relative terms, it’s almost precisely in line with previous years’ estimates.

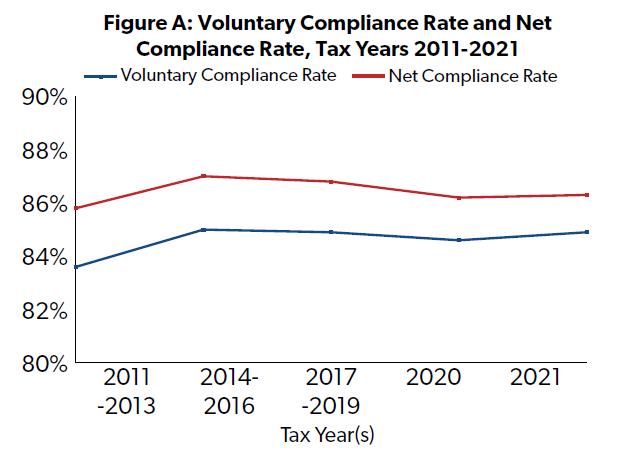

The IRS has come out with five separate estimates of the size of the tax gap over the past couple years, covering tax years 2011-2013, 2014-2016, 2017-2019, 2020, and 2021. Over that period, particularly the four most recent estimates, the estimated voluntary and net (accounting for late payments and enforcement actions) compliance rates have remained largely unchanged, as illustrated by Figure A.1

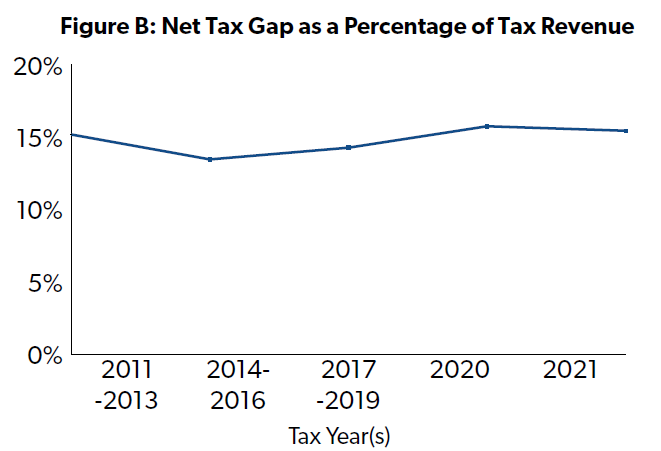

Similarly, as revenue collections increase, it can be expected that the tax gap will increase as well — even if compliance remains roughly the same. Figure B shows that as a percentage of total tax revenue, the tax gap has remained fairly constant.

Therefore, while the size of the tax gap continues to increase, that’s mostly a function of economic growth and increased tax collections. Put another way, the more the IRS taxes, the more it will also not tax.

The other consideration is the pandemic. The IRS’s estimated nonfiling tax gap nearly doubled between the 2017-2019 estimate and the 2021 estimate, from $41 billion to $77 billion. Presumably, much of this is due to Americans who took up gig jobs during the pandemic but did not file returns on their income, either willfully or because they were unaware of their obligation to report this income to the IRS.

But this should not be cause to conclude that gig work is becoming an underground, untaxed economic activity. Absent proof to the contrary, it is best to assume ignorance rather than malice — a maxim that holds just as true for tax noncompliance as any other wrong. Unfortunately, noncompliance in the gig economy is often cited as a reason to impose new draconian reporting and compliance requirements.

And in this case, it is likely that many of these non-filers were first time gig workers who chose to bridge a gap between traditional jobs with some short-term gig work. Given the non-traditional and temporary nature of these jobs, not to mention the general disruption coming from the pandemic, they may simply have been unaware that the income they earned was taxable. That’s a unique circumstance that is unlikely to hold true moving forwards — and to the extent it does, the first tool employed by the IRS to combat it should be taxpayer education, not enforcement.

How Accurate is the Tax Gap Estimate?

As previously noted, any estimate of the size of the tax gap must inherently be taken with a grain of salt. Any accurate reckoning of the size of the tax gap would necessitate a precise knowledge of the sources and scope of noncompliance — something that would make the IRS’s job in closing the tax gap far easier.

The IRS itself would probably be the first to say that its estimate of the size of the tax gap is imprecise. Former IRS Commissioner Chuck Rettig made headlines and spurred a renewed focus on IRS enforcement funding two years ago by claiming that his personal opinion was that it was “not outlandish to believe that the actual tax gap could approach and possibly even exceed $1 trillion per year.”

Though NTUF wrote at the time exactly why the “$1 trillion tax gap” number that some subsequently latched on to was inaccurate, we also acknowledged that the true number was likely higher than the official $381 billion IRS estimate that was the most up-to-date estimate at the time.

Even the IRS’s updated estimates generally apply the same methodology to newer years of data, basing its estimates of taxpayer compliance around the last round of completed audits from tax years 2014-2016. It also makes little attempt to estimate the scope of noncompliance due to unreported gains from cryptocurrency and untaxed assets in offshore holdings, for example.

On the one hand, the IRS elevates the exaggerated gross tax gap figure, on the other hand, the agency does not provide adequate transparency on key factors in its methodologies. Generally, statistical analyses of this nature include a consideration of error rates or indicate a confidence interval. But the IRS notes, “Because multiple methods are used to estimate different subcomponents of the tax gap and then are projected into future tax years, no standard errors are reported.” Table 8 of the IRS’s projection notes thirteen different methodologies involved in estimating components of the measured tax gap. The information provided along with that table does not include a reporting of the standard error rates for those components. The IRS does at least discuss some points of uncertainty in the data, including sampling errors, measurement errors, estimation errors, coverage errors, and projection errors.

And while the IRS’s breakdown of the tax gap by tax subcategory makes logical sense on its face, it does not contribute to a good understanding of the driving factors behind the tax gap. After all, the umbrella of the individual income tax contains everything from traditional W-2 income to pass-through income and gains from cryptocurrency. A thorough understanding of the sources and scope of noncompliance from one of these sources of income does little to lend an understanding to the sources and scope of noncompliance for another.

What Does This Tax Gap Estimate Tell Us?

Even acknowledging the limitations of this latest estimate of the tax gap, there remain important insights to be gleaned.

Non-Filing and Underreporting Are Driving Increases

While the underpayment gap remained steady, the nonfiling and underreporting gaps grew by 87 percent and 13 percent respectively between tax years 2020 and 2021. Underreporting remains a far larger problem in terms of volume (an estimated $582 billion compared to $77 billion for underpayment), but non-filing is increasing at a much faster rate.

As mentioned before, many of these taxpayers were likely either unaware that income from what they viewed as temporary side hustles was taxable — or, if they did realize, may not have been aware of their obligation to remit self-employment taxes and quarterly estimated payments. And indeed, the individual income tax non-filing tax gap increased between the time before the pandemic and after — more than doubling between 2019 and 2021. Underreporting under the individual income tax and self-employment taxes increased by around 26 percent, while all other components of the underreporting tax gap increased by just 3 percent.

Closing the Tax Gap Would Require Targeting Average Americans

Rhetoric around the tax gap reports often suggests that the tax gap can be closed by going after unsympathetic wealthy tax cheats, but much of the tax gap comes from small businesses and lower-income taxpayers who are likely contributing to the tax gap unintentionally.

Small businesses, for example, are the single biggest driver of the tax gap, accounting for roughly half of the tax gap in 2021 between self-employment taxes, pass-through income, and corporate tax on small corporations. Credits targeted at low-income taxpayers add a further 7 percent, or $51 billion. Large corporations, meanwhile, make up less than 4 percent of the tax gap.

These fundamental facts, along with the fact that the IRS has consistently found targeting lower-income taxpayers with less means to challenge audits to be more productive, are why average Americans almost inevitably get caught up in stepped-up IRS enforcement efforts. It’s simply impossible to comprehensively address the tax gap without doing so.

These complications show why it is a mistake to present the IRS’s tax gap estimate as the metric of tax cheating in the country. The tax code is incredibly complex, particularly to taxpayers without experience dealing with its most confusing portions (or the ability to hire someone with said experience), and it is extremely easy for taxpayers with the best of intentions to make mistakes. Of course, intentional tax evasion does exist, but the “guilty until proven innocent” position often taken by the IRS in tax disputes does a disservice to many average taxpayers.

The Ideal Tax Gap Is Not Zero Dollars

Focusing on the sheer size of the IRS’s tax gap estimate can disguise the fact that it is neither possible nor particularly desirable to reduce the tax gap to $0. Increased encroachment into taxpayer’s private information yields diminishing returns, and there exists a point at which the potential revenue to be gleaned from additional reporting and disclosure requirements are outweighed by the compliance burden on taxpayers (not to mention the privacy costs of government intrusiveness).

This may seem like an obvious statement, but a $625 billion tax gap does not equate to a potential $625 billion in additional annual revenue. While some of this revenue could be recaptured by expanded enforcement efforts, by no means could all of it be.

This is particularly worth noting in the context of some proposed enforcement efforts that would greatly increase taxpayer compliance costs in terms of both time and money for minimal revenue reward. An example of this is the IRS’s continued failure to provide a reasonable estimate for the increased taxpayer burden of the coming changes to Form 1099-K reporting requirements which will require millions of taxpayers to file Form 1099-Ks over transactions that may or may not even be taxable.

For another example, the IRS estimates that the new reporting requirement for digital asset transactions (cryptocurrencies) will result in an inflow of 8 billion information returns annually impacting 13 to 15 million taxpayers. This inflow would be twice as much as all the information returns the IRS currently collects. Meanwhile, the IRS Project Director for Digital Assets said, “Our technology, the way it is today, will not support the data and the volume.”

Similarly, past proposals to give the IRS access to details on all financial accounts exceeding a certain threshold (gross transactions exceeding either $600 or $10,000 at different points) would have represented an enormous intrusion into the personal information of millions of average taxpayers and a gigantic compliance burden for financial institutions.

These proposals and reporting regimes entail enormous compliance burdens for businesses and taxpayers, as well as significant intrusions into taxpayer privacy when the IRS has yet to prove it takes protecting taxpayer data seriously enough. A continued focus on enforcement without acknowledgement of the associated costs is likely to yield even more intrusive proposals.

Conclusion

Even though the estimated size of the tax gap continues to grow in absolute numbers, it is important to consider these numbers in context. Jumping to an inaccurate conclusion that noncompliance is a growing problem is likely to result in hasty, poorly-considered decisions that lead to more aggressive enforcement methods.

Any effort to reduce the size of the tax gap must be cognizant of the costs. Out-of-compliance taxpayers are not solely intentional tax cheats — many are simply confused and misled by our labyrinthine tax code. Education and help for taxpayers who make honest mistakes has just as much of a place in efforts to address the tax gap as punishment for intentionally delinquent taxpayers. What’s more, policymakers must recognize that increasingly draconian and intrusive enforcement methods are likely to impact compliant taxpayers as well as noncompliant ones.

While the dollar figure headlining this year’s IRS estimate of the tax gap has grown, the actual problem remains largely the same. Without understanding that context, policymakers are likely to respond to this updated estimate with exactly the wrong solutions: a more complicated tax code, and more aggressive enforcement.

1 The IRS released tax gap estimates as three-year averages between 2011 and 2019. For 2020 and 2021, the IRS released individual year estimates.