Key Facts

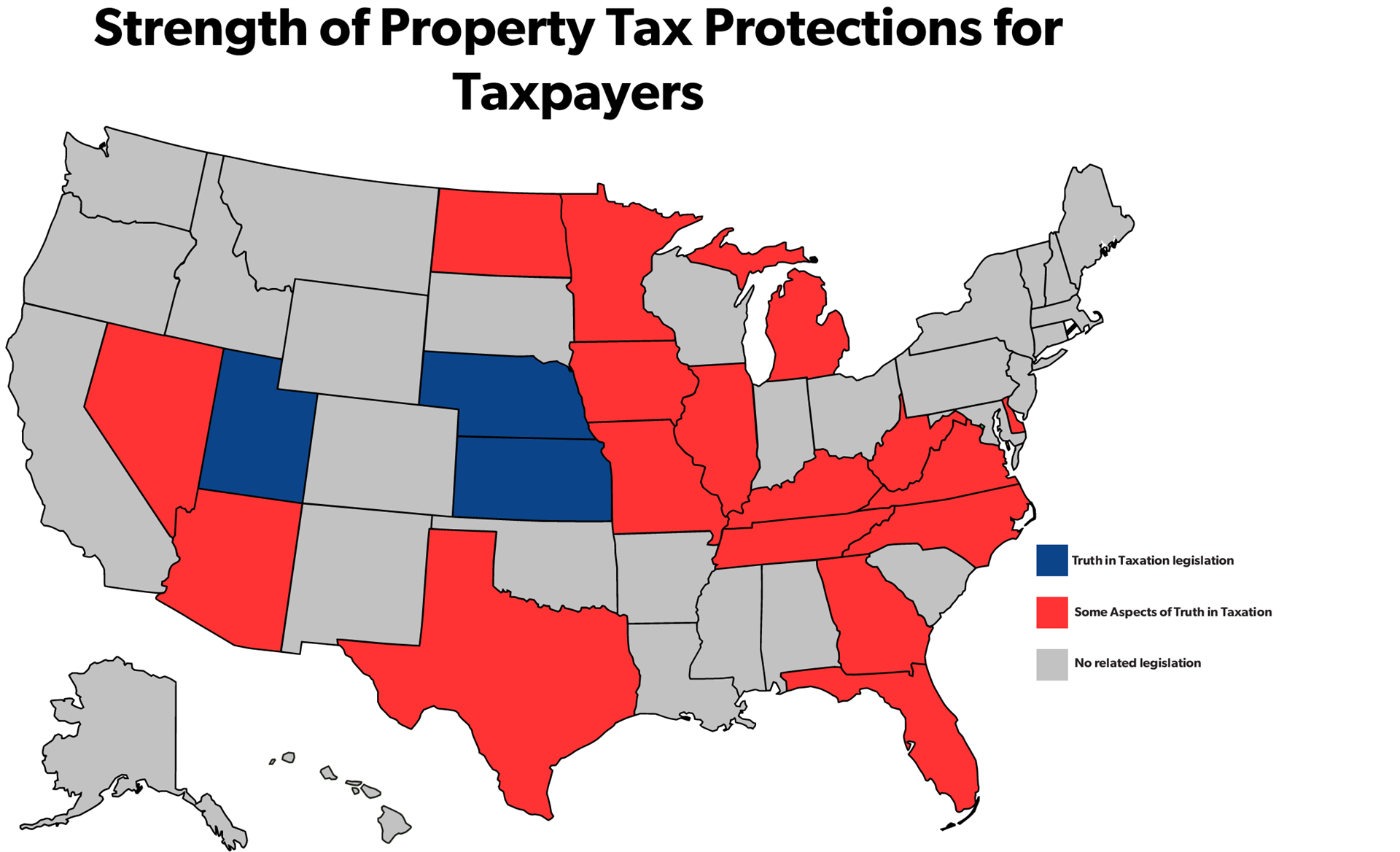

Drastic inflation in the early 2020s led to substantial property tax increases across the U.S. and debates in many state legislatures on how to address runaway costs

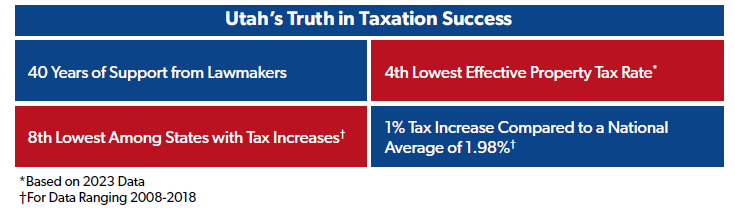

Utah pioneered Truth in Taxation legislation to prevent rampant property tax increases without stifling necessary government functions

- Kansas and Nebraska recently adopted similar legislation to curb their own problems with property tax growth

- The current economic and political climate presents an opportunity for state lawmakers to adopt Truth in Taxation

Executive Summary

Truth in Taxation legislation, created in Utah in 1985 and subsequently adopted in Nebraska and Kansas, has proven effective at countering increasing property taxes in an inflationary environment. Prior to the institution of Truth in Taxation—a combination of levy limit and public notice—in Utah, taxpayers in the state were facing some of the highest property tax rates in the country. Following the implementation of Truth in Taxation, Utah is now consistently among the states with the lowest property taxes in the country; in 2021, Utah was ranked the state with the seventh lowest property tax rate.

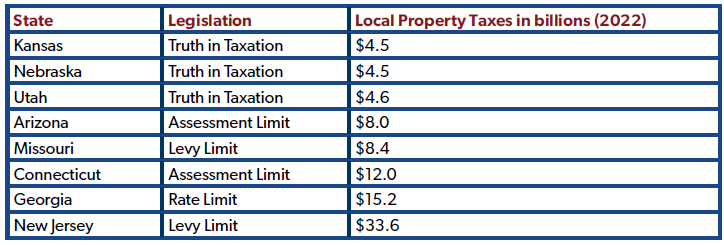

Property taxes remain a significant part of state and local tax revenue—$23 billion, or 27% of all state and local revenue, in 2022. Polls consistently rank property taxes as one of the most unpopular taxes in the United States. Numerous states have consequently seen various property tax reforms: California Proposition 13, Massachusetts Proposition 2½, Oregon Measure 47, and the Colorado Taxpayer Bill of Rights were all enacted after a period of sustained high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s. Today, after another period of record inflation, there is again pressure for property tax reform legislation. State policymakers should consider Truth in Taxation to bring property tax increases under control

What Is Truth in Taxation?

Truth in Taxation combines a property tax levy limit and two mechanisms for expanded transparency for taxpayers. A levy limit controls the total revenue collected each year in contrast to a rate limit or assessment limit (a cap on increases in the assessed value of a property). Levy limits existed prior to the 1970s tax revolt but were only found in five states (Arizona, Colorado, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Utah). Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, twenty-one states adopted levy limits, with more following suit in the 1990s.

Transparency with regard to how much households pay and how much tax increases affect taxpayers is necessary for good policymaking. Truth in Taxation requires sending each household a notice showing how much its individual taxes would increase from a proposed change and indicating the date a public hearing will be held to address the change. At the public hearing held to address the relevant tax rate increase, taxpayers can voice their opinions on the increase and officials hold a public vote on whether to approve the increase.

To effectively protect and inform taxpayers while providing states and localities with sufficient revenues, Utah brought these elements together when it implemented its Truth in Taxation legislation in 1985. By limiting automatic, exponential property tax growth and involving the voice of citizens in the process of raising taxes, taxpayers benefit.

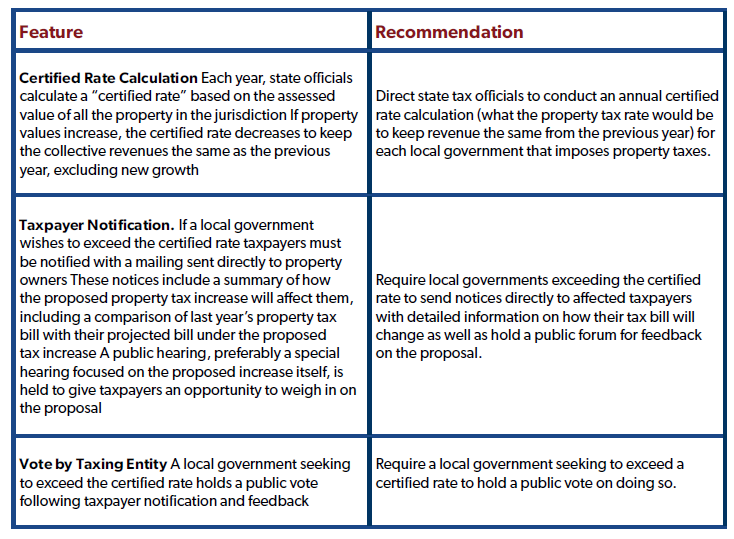

Truth in Taxation has three main elements:

- Calculations of Certified (or Rollback) Rates: Officials calculate what property tax would be to raise the same revenue next year based on new assessed values. The rate may float up or down for both the locality and individuals’ property taxes to match the same amount collected.

- Transparency with Notices to Taxpayers: When officials wish to increase the tax levy, they are required to provide notice and disclosure to taxpayers outlining how much the increase is, how much it will affect their parcel’s tax, the reasons for the increase, and the date and location of a public hearing regarding the increase. The information regarding the public hearing is published in a local, well-distributed newspaper and online.

- Accountability Through Public Hearing and Vote by Taxing Authority: Public hearings allow constituents to express their opinions on property increases and force a degree of accountability on public servants. These hearings focus on whether to exceed the certified rate. Following hearings and feedback from taxpayers, officials vote on whether to increase the tax levy. Taxpayers tend to oppose property taxes and will vote against increases in most cases. This vote protects taxpayers but ensures localities are not devoid of funds when they are needed.

For example, assume a locality collects $1,000,000 based on a 1% tax on all property in its jurisdiction. The following year, the average property value in the area increases and, with the previous year’s 1% tax rate, the collection would rise to $1,200,000. With the levy limit under Truth in Taxation, the tax rate would float down to .833% to keep the money collected at $1,000,000. Thus, some properties may experience a slight increase in their property tax, but the average property will have no increase.

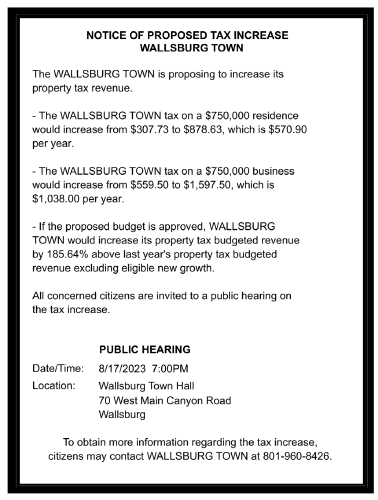

If the agency decides it wants to increase revenues, the transparency aspect of Truth in Taxation is activated. The taxing entity sends out a notice that shows the current tax rate on the home of the recipient and how much the potential tax increase would cost. Additionally, the notice includes the date, time, and place of the public hearing in which officials will discuss the proposed tax increase. A more general notice as shown above is posted on the website of the taxing agency and in a widely circulated newspaper.

out a notice that shows the current tax rate on the home of the recipient and how much the potential tax increase would cost. Additionally, the notice includes the date, time, and place of the public hearing in which officials will discuss the proposed tax increase. A more general notice as shown above is posted on the website of the taxing agency and in a widely circulated newspaper.

Though the state is imposing no limits on local governments’ ability to set their own property tax rates, simply engaging taxpayers in the process has a proven track record of restraining “silent tax increases.”

Truth in Taxation in Practice

Utah

Before adopting Truth in Taxation, Utah experimented with various property tax reforms. In 1947, Utah legislators lowered the definition of assessed value from 100% of “full cash value” to 40%. Lawmakers again lowered the definition from 40% to 30% in 1961 and again from 30% to 25% in 1969. Officials in Utah attempted to match the legal definition of assessments to assessments in practice across the state and paired these changes with various systemic changes to the state approach to property tax.

The Supreme Court of Utah invalidated the state’s property assessment laws in the 1984 case Rio Algom Corporation v. San Juan County. This forced state legislators to completely overhaul Utah’s approach to assessments and property tax. After making the change back to full fair market value for assessments, legislators enacted the Tax Increase Disclosure Act in 1985. This legislation, paired with consistent property assessments at 100% of value, stabilized Utah’s property tax.

The overhauled tax system allowed Utah to sustainably collect property taxes, and, as a result of the stable revenue stream, sizable property tax reductions were implemented in 1995, 1996, and 1998. Aside from changes to the date requirements for hearings, Utah politicians have changed very little with Truth in Taxation in 40 years. In 2009 and 2010, website notices were added to modernize notification to taxpayers.

Nebraska

Nebraska adopted Truth in Taxation in 2019 after decades of struggling to combat high property taxes. Past attempts focused on revenue limits across all tax collections and setting rate limits on property taxes. Rate limits could be surpassed with a vote from taxpayers, allowing localities to increase revenues for designated projects. Through the 2010s, Nebraska had the sixth fastest increase in housing prices, with prices increasing 26% from 2008 to 2018. Despite the rate limits, property taxes closely adhered to the rapidly increasing assessments. Between 2013 and 2018, many counties in Nebraska lowered tax rates but, due to rising assessments, levied taxes continued to increase. In Buffalo County, the average tax rate fell nearly 0.4% over this five year period but the total taxes levied increased by over $23 million.

Nebraska adopted Truth in Taxation with the passage of LB 103 in 2019, creating a certified rate, requiring newspaper notices of increases, and requiring public hearings before a vote. Initially, notifications of the increase and of public hearings were only published in newspapers rather than mailed directly to taxpayers. This was partially remedied in 2021 with LB644, the Property Tax Request Act, which requires direct mail to taxpayers but notably does not require explaining how a taxpayer’s bill would increase in the event the tax increase were approved.

Nebraska’s law differs most from Utah’s in setting an “allowable growth percentage” of 2%. In other words, property taxes can automatically increase 2% per year without triggering the taxpayer protection of Truth in Taxation. This increased percentage diminishes the relevance of Truth in Taxation as revenue can automatically increase without notifying taxpayers and without receiving feedback on the use of funds.

The problem of rising property taxes was exacerbated in 2020 by the Nebraska Property Tax Incentive Act, which increased the state income tax credit for property tax from 6% to 30%. While this took some burden off of taxpayers and made them less likely to complain about increased rates, it also incentivized further rising property taxes. With less scrutiny from taxpayers, local governments and taxing authorities are more likely to raise taxes. Despite eagerness to ameliorate the property tax burden, the expanded credits may diminish the effectiveness of the state’s Truth in Taxation measure in restraining property tax increases.

Kansas

In early 2021, Senate Bill 13 established the revenue-neutral rate, notice, and public hearings requirements of Truth in Taxation. The following year, more than half of Kansas’s taxing authorities voted against raising taxes as a result of Truth in Taxation. In 2023, the Kansas Senate passed an assessment limit in SCR 1611, but the bill ultimately died in the House, allowing the Truth in Taxation system to continue.

Truth in Taxation sought to fix problems not addressed by the previously used system, the property tax lid. This hard levy limit passed in 2015 as part of a last minute deal between Republicans and Democrats in the state legislature to offset a sales tax increase in the same bill. The property tax lid required voters to approve property tax levies exceeding the previous year’s levy adjusted for inflation. Proponents of the bill argued that although property tax rates had increased little from 2010 to 2014, property tax levies had increased. This is the silent tax increase problem tied to assessment and inflation increases that Truth in Taxation directly addresses via its soft levy limit.

How Truth in Taxation Compares to Other Reforms

The high inflation in the 2020s has taxpayers pushing their legislators for changes to property tax mirroring the 1970s. Truth in Taxation is not the only policy adopted in the past few decades and it is important to look at how other major changes have affected state property taxes and revenues. In some cases, states have adopted laws that resemble parts of Truth in Taxation but fail to encompass all of the elements that make the policy effective.

Florida

In 1980, state legislators passed the Truth in Millage (TRIM) act. Local taxing authorities calculate a certified rate and are required to advertise the tax increase via mail but no lowering of the rate occurs. The TRIM notice is sent annually and contains reference to a certified rate as a comparison to the proposed increase, but, unlike in Utah, the rate isn’t used to automatically revert revenues each year. Notices show which taxing entities are applying property taxes and give dates and times for public hearings. TRIM does not require hearings separate from standard budget hearings, meaning representatives of the taxing authority are less likely to hear complaints against property tax increases in particular.

Currently, Florida provides two property tax exemptions and an assessment limit meaning taxpayers pay substantially less on the value of their homes. Despite these mechanisms, property taxes continue to skyrocket. Recently, Governor Ron DeSantis called for an outright abolition of the property tax with local revenues supplemented by state spending, which Tax Foundation found would total between $2–4 billion.

Florida could easily move to Truth in Taxation. State jurisdictions already calculate the certified rate each year. Rather than simply publish this information, Florida legislators should modify TRIM to apply the certified rate each year to limit revenue growth. Unless there is a proposed increase in revenue, TRIM notices would not be required, saving taxpayers money on the printing and delivery of mailings. Separate public hearings focused on property tax increases would allow taxpayers to more effectively voice their opinions on increases and allow officials to explain when and why increases may be necessary.

Illinois

Legislators in Illinois passed the Truth in Taxation Act in early 1981, predating Utah’s law but lacking elements that make Truth in Taxation effective. Rather than approach levy limits with a certified rate, Illinois’s law activates if the tax levy is greater than 105% of the previous year’s levy. While a 5% increase seems minimal from year to year, the steady increase of property tax without notification is part of what Truth in Taxation is intended to combat. This 5% increase is disproportionately spread between taxpayers and over a five or ten year period could lead to a 25–50% increase with no required public notice.

Even when the 105% increase in the levy is surpassed, the Illinois notice procedure is substantially less targeted, and, as a result, less transparent. Rather than mailing taxpayers information outlining how much their individual property tax will increase, Illinois’s law only requires a notice demonstrating the levy of the current year, the levy of the preceding year, and the percentage of the increase between the two. Until 2016, these notices were required solely in a general circulation newspaper. A 2015 amendment required taxing districts to post notices on their websites and an amendment in 2024 added requirements for the location and timeframe of the notices. Adding online notices is a step in the right direction for transparency on the tax increases but a far cry from the Truth in Taxation process described above.

The element most closely hewing to a functional Truth in Taxation system is the hearings that follow the public notice. Taxing agencies in Illinois must hold hearings specifically on the levy increase, allowing authorities to explain the reasons for the increase and taxpayers to voice their dissent. Unfortunately, these hearings are largely meaningless as no vote is held in their wake. The head of the taxing district must sign off certifying the tax increase, but the signature of one official is a far cry from a documented vote from officials. It is much easier for taxing districts to avoid accountability for tax increases without a vote and the grievances voiced by taxpayers have far less strength.

In 2025, Illinois had the second highest property tax rate in the country with an effective rate of 2.07%. Taxes on a home of median value in Illinois would cost a homeowner over $5,000 per year. The current system fails to stop or even slow the rapid increase in cost to Illinois’ taxpayers. An overhaul to more closely resemble a real Truth in Taxation mechanism would ease the burden on property owners.

Iowa

In 1977, Iowa legislators capped assessment growth at 4% and tied residential and agricultural property values to one another. In 2013 and 2019, state legislators passed property tax reforms that lowered the assessment growth cap to 3% and created a 2% cap on budgets. The 2019 law also took steps toward Truth in Taxation by requiring public hearings prior to a vote by authorities to exceed the 2% cap.

In response to the continued growth of property taxes, legislators drafted expansive reforms in 2023. These included a consolidation of 15 different levies into one run by cities and a levy limit on that general fund of $8.10 per $1,000 in taxable value. The law also moved Iowa closer to Truth in Taxation by establishing a separate public hearing on proposed property tax increases and adding direct notification of the meeting and tax increases to property owners. The notices demonstrate how the proposed increases compare to the previous fiscal year, both with the difference between the two levies and using a hypothetical property valued at $100,000. Political subdivisions must also outline the projects or programs for which the increased revenue will be used.

Most of Iowa’s Truth in Taxation-related provisions went into effect in 2024. To strengthen its laws to more closely match the robust Truth in Taxation legislation which Utah and Kansas adopted Iowa lawmakers must make a few changes. Legislators should remove the soft cap on revenue growth, establish a true certified rate, and include details on how a rate increase would affect individual properties rather than using a hypothetical.

Conclusion

Rapid growth of property taxes is a widespread problem for state and local governments. Seeking solutions, state legislators have implemented a variety of policies. These are often stop-gap measures or completely hobble local governments. The Truth in Taxation policy pioneered and improved by Utah is the most effective way to address inflation and assessment driven property tax increases. The high degree of transparency and involvement of taxpayers leads to fewer tax increases and less uproar over tax rates when they do rise.