U.S. International Trade Commission

In the Matter of:

Distributional Effects of Trade and Trade Policy on U.S. Workers

Investigation Number 332-587

Posthearing Brief from Bryan Riley

Director, Free Trade Initiative

National Taxpayers Union Foundation

May 3, 2022

National Taxpayers Union Foundation (NTUF) is a non-partisan research and education organization dedicated to showing Americans how taxes affect them. Policymakers often use innocuous phrasing referring to tariffs on foreign countries – for example, “tariffs on China” or “tariffs on France.” But tariffs are in fact taxes on American workers who buy imported goods. We appreciate this opportunity to comment on how these tariffs affect U.S. workers, particularly those whose voices have historically been disregarded in order to appease politically powerful interest groups.

U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai requested that the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) investigate the potential distributional effects of goods and services trade and trade policy on U.S. workers by skill, wage and salary level, gender, race/ethnicity, age, and income level, especially as they affect underrepresented and underserved communities, including Black, Latino, and LGBTQI+ persons.[1] This investigation provides an opportunity for the USITC to document how U.S. trade restrictions, including those maintained by the Biden administration, continue to inflict harm on underrepresented and underserved communities.

In 1947, NAACP founding member Oswald Garrison Villard observed:

The essential immorality of the tariff is that it constitutes class legislation in the interest of relatively small minorities – manufacturers, farmers, etc., and thus creates specially favored, privileged groups. It is immoral for any democratic government to use its power to aid some and not all of its citizens. Tariffs not only put the government into partnership with certain classes, but compel the government to levy upon all citizens who use the goods that are protected in order to line the pockets of the producers.[2]

NTUF urges the USITC to consider the following observations.

Women, African Americans, and Hispanic Americans tend to support trade and oppose tariffs. While many people claim to speak on behalf of various demographic groups, opinion surveys of how Americans feel about trade are revealing:

- 71 percent of non-whites and 57 percent of females view trade as more of an opportunity for economic growth than a threat.[3] (2022)

- 71 percent of Hispanics and 53 percent of Blacks say free trade agreements have been a good thing for the United States.[4] (2015)

- 52 percent of women think increased tariffs with trading partners will be bad for the United States.[5] (2015)

- 66 percent of Hispanics and 59 percent of African Americans say the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has been good for the United States.[6] (2017)

These groups’ pro-trade views have consistently been stifled by politically connected groups that benefit from tariffs.

Tariffs are regressive taxes on American workers. There is no shortage of studies, including from the USITC, documenting the impact of U.S. tariffs on poverty. For example:

- “[T]ariffs fall disproportionately on the poor.”[7] (2018)

- “[T]ariffs function as a regressive tax that weighs most heavily on women and single parents.[8] (2017)

- “Tariffs are easily the most regressive of all U.S. taxes, forcing the poor to pay more than anyone else.”[9] (2022)

- “[T]he lowest income consumers, families with young children, and women have paid a disproportionately high cost for recent U.S. trade wars.[10] (2021)

Since workers are also consumers, U.S. tariffs are a regressive tax on the American labor force. Eliminating tariffs would represent a progressive tax cut, benefiting low-income families the most.

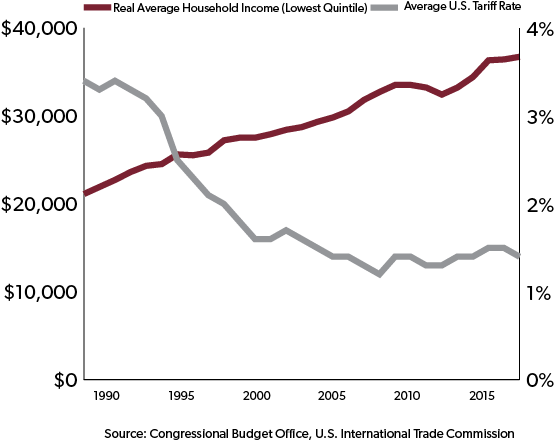

Predictably, low-income Americans prospered as the United States slashed tariffs. From 1989 to 2017, just before U.S. tariffs began to rise, the real income of the poorest one-fifth of U.S. households increased by 73.9 percent as tariffs were cut in half.[11] [12]

Figure 1: Real Average Household Income After Taxes and Transfer Payments vs. Average U.S. Tariff Rate

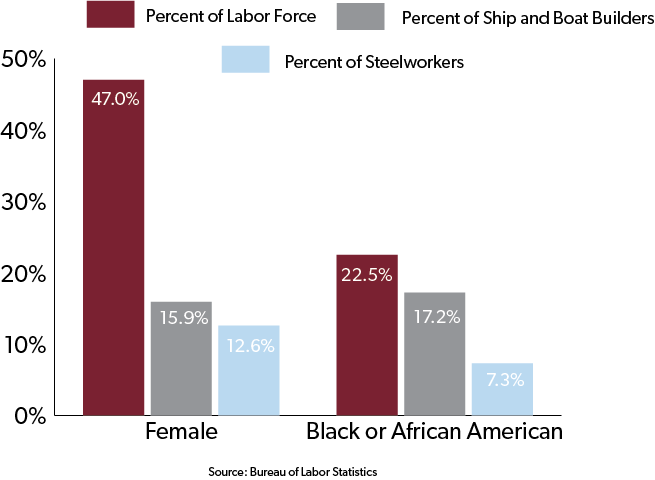

Current U.S. trade policies often run counter to the Biden administration’s stated efforts to advance equity and diversity.[13] Consider two examples of U.S. trade policy and their impact. The Biden administration and its predecessors have maintained a variety of tariffs and other barriers designed to benefit steel producers at the expense of American steel users.[14] In addition, for decades the federal government has prohibited the use of foreign-built ships to transport cargo domestically. Each of these barriers disproportionately benefit white, male workers at the expense of others.

Figure 2: Female and African American Steelworkers and Shipbuilders (2021)

When Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai boasted of the Biden administration’s efforts to protect the U.S. steel industry, and when Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg endorsed the protectionist Jones Act and its shipbuilding restrictions, they failed to mention that these actions primarily benefit a relative small number of predominantly white, male union workers at the expense of every American worker who makes or uses goods containing steel or who ships goods domestically.[15] [16]

According to the Coalition of Metal Manufacturers and Users, over 6.2 million Americans work in industries that use steel, while the steel industry employs only 141,700 workers.[17] A study from The Trade Partnership found that for every steel and aluminum industry job that could be gained through tariffs, 16 jobs would be lost, and two-thirds of the losses would be inflicted on Americans with production and low-skill jobs.[18] Economists Kadee Russ and Lydia Cox estimated that the number of jobs in U.S. industries that use steel or inputs made of steel exceeds the number of jobs involved in the production of steel by roughly 80 to 1.[19]

But the overall cost of steel tariffs is even more insidious, since these barriers inflate the price of cars, appliances, and anything else made with steel for more than 122 million U.S. households.[20]

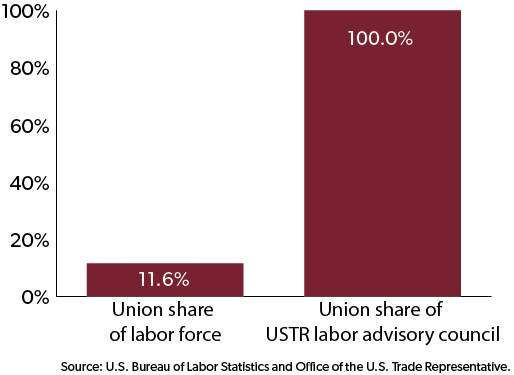

U.S. trade policy excludes input from non-union workers. Congress has established several advisory committees to ensure that U.S. trade policy reflects U.S. public and private sector interests from a variety of different perspectives. One of these, the Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations and Trade Policy, is supposed to represent the views of U.S. workers from a wide range of economic sectors that are affected by international trade policy. The committee’s charter claims that “the need to obtain divergent points of view on issues before the Committee is of great importance to the development of the Committee’s recommendations.”[21]

However, despite representing just 11.6 percent of the U.S. private sector labor force, unions comprise 100 percent of the membership of the Labor Advisory Committee.[22] [23] The Biden administration has denied the opportunity for more than 120 million American workers who are not represented by labor unions to be represented on the Labor Advisory Committee.

Figure 3: No Non-Union Workers Allowed on USTR Labor Advisory Committee (2021)

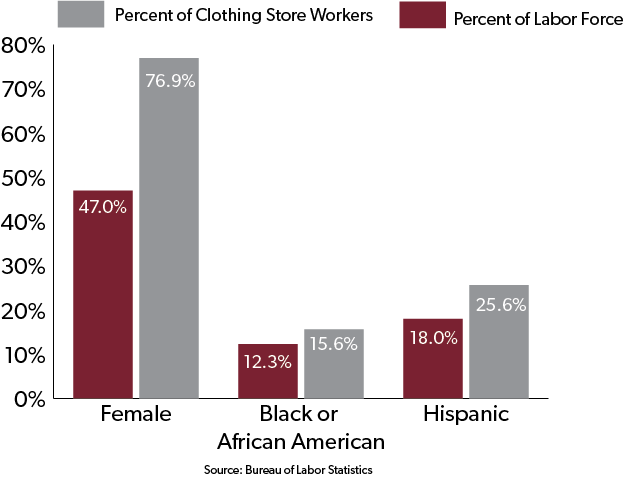

Trade barriers harm retail workers, who are disproportionately Black, Hispanic, and female. U.S. trade barriers increase the cost of many of the goods retail workers sell, reducing their earning power, while also increasing the cost of goods they buy.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, retail workers are more likely to be Black, Hispanic, or female relative to the overall U.S. labor force.[24] To provide one specific example, in 2021, the average U.S. import tax for imported clothing was 14.7 percent.[25] In addition to representing a regressive tax on the U.S. labor force as a whole, taxes on imported clothing particularly harm female, Hispanic, and Black or African American workers, who account for a significant chunk of clothing store employment.

Figure 4: Excessive Apparel Tariffs Penalize Clothing Store Workers (2021)

Trade barriers impose costs on LGBTQI+ workers. Gay and lesbian persons largely work in industries that do not directly benefit from U.S. trade barriers.[26] As a result, the impact of U.S. trade policy on these workers may be even more negative than the impact of trade barriers on the population as a whole. On average, they are less likely than other workers to benefit from tariff protection, while still being on the hook for inflated prices for high-tariff goods.

U.S. tariffs are biased against female workers. Although the exact amount is subject to debate, the current tariff schedule applies higher tariff rates to women’s clothing than to men’s. According to a 2015 study, the average tariff on clothing for females was 15.1 percent, while the average tariff on clothing for males was just 11.9 percent.[27] A USITC study concluded that the differential was even greater, calculating that the tariff burden on women’s clothing was nearly twice as high as the tariff burden on men’s clothing.[28] Any examination of the impact of tariffs on U.S. workers should include a closer look at how the tariff code discriminates against female workers.

Buy American mandates inflate costs and reduce the benefit of federal projects. Buy American laws and regulations require the government to pay inflated prices for domestically produced goods even when more affordable supplies are available from abroad. President Dwight D. Eisenhower commented: “[I]t is improper policy, unbusinesslike procedure and unfair to the taxpayer for the Government to pay a premium on its purchases.”[29] Scholars at the Peterson Institute for International Economics have calculated that Buy American policies cost taxpayers $94 billion as of 2017.[30]

Unfortunately the Biden administration has chosen to impose costly new Buy American mandates, apparently without even conducting a preliminary analysis on how these restrictions would affect U.S. workers or underserved communities.[31]

Perhaps that’s because such an analysis would be likely to show they will result in a combination of higher costs for taxpayers, a constrained ability to fund new federal projects, and fewer opportunities for U.S. workers to supply projects undertaken by foreign governments.

Recommendations:

NTUF encourages the USITC to further examine how protectionist policies may harm underrepresented Americans in order to benefit those in privileged groups. In the past, the USITC provided annual reports on the impact of U.S. import restraints, often referencing the regressive impact of tariffs. The USITC should reinstitute these annual reports, including an analysis of how U.S. import barriers affect underserved persons. It is our hope that accurate analysis from the USITC will encourage the Biden administration and Congress to pursue a worker-centered policy that reduces the damage tariffs inflict on Americans.

While beyond the purview of the USITC, NTUF further recommends that, to address the concerns raised in the Biden administration’s request letter, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) should include a breakdown of U.S. barriers to international trade and investment in its annual National Trade Estimate Report on Trade Barriers. These barriers are often the costliest to U.S. workers, and unlike foreign barriers, the federal government has the ability to eliminate them without engaging in prolonged international negotiations. USTR should also reconstitute its Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations and Trade Policy to represent all segments of the U.S. labor force and not just union workers.

[1] Ambassador Katherine Tai, letter to USITC Chair Jason Kearns. October 14, 2021. Retrieved from https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/RL_ITC_Distributional_Effects.pdf.

[2] Villard, Oswald Garrison, Free Trade, Free World (New York, Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, 1947), page 34.

[3] Jones, Jeffrey M., “U.S. Views of Foreign Trade Nearly Back to Pre-Trump Levels,” Gallup, March 10, 2022. Retrieved from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/390614/views-foreign-trade-nearly-back-pre-trump-levels.aspx.

[4] Pew Research Center, “Free Trade Agreements Seen as Good for U.S., But Concerns Persist,” May 27, 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2015/05/27/free-trade-agreements-seen-as-good-for-u-s-but-concerns-persist/.

[5] LaLoggia, John, “As new tariffs take hold, more see negative than positive impact for the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, July 19, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/07/19/as-new-tariffs-take-hold-more-see-negative-than-positive-impact-for-the-u-s/.

[6] Stokes, Bruce, “Views of NAFTA less positive – and more partisan – in the U.S. than in Canada and Mexico,” Pew Research Center, May 9, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/05/09/views-of-nafta-less-positive-and-more-partisan-in-u-s-than-in-canada-and-mexico/.

[7] Gailes, Arthur, Tamara Gurevich, Serge Shikher, and Marinos Tsigas, “Gender and Income Inequality in U.S. Tariff Burden,” USITC, August 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/working_papers/gender_tariff_1.html.

[8] Furman, Jason, Katheryn Russ, and Jay Shambaugh, “U.S. tariffs are an arbitrary and regressive tax,” VoxEU, January 12, 2017. Retrieved from: https://voxeu.org/article/us-tariffs-are-arbitrary-and-regressive-tax.

[9] Gresser, Ed, “I’ll Tax Your Feet,” Wall Street Journal, April 4, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/tax-your-feet-tariffs-good-unfair-income-inequality-regressive-shoes-shirts-imports-high-end-exempt-systemic-inequity-11649111269.

[10] Reynolds, Kara M., “Costs of Trade Wars: The Distributional Consequences of US Section 301 Tariffs Against China,” SSRN, June 8, 2021. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3862764.

[11] “The Distribution of Household Income, 2018: Supplemental Data,” Congressional Budget Office, August 4, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57061.

[12] Customs Value and Calculated Duties, USITC. Retrieved from dataweb.usitc.gov.

[13] The White House, “President Biden’s FY 2023 Budget Advances Equity,” March 30, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2022/03/30/president-bidens-fy-2023-budget-advances-equity/.

[14] Lincicome, Scott, “U.S. Steel and the Ubiquitous ‘Market Failure,’” May 5, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.cato.org/commentary/us-steel-ubiquitous-market-failure.

[15] Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai, “What new steel and aluminum deals mean for American families,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 28, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.commerce.gov/news/op-eds/2021/11/op-ed-commerce-secretary-gina-raimondo-and-us-trade-representative-katherine.

[16] “Buttigieg: ‘I Strongly Support the Jones Act,’” Seafarers International Union, March 26, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.seafarers.org/buttigieg-i-strongly-support-the-jones-act/.

[17] Coalition of American Metal Manufacturers and Users, “U.S. Metal Manufacturers and Users to Secretary Raimondo: Data Show Section 232 Steel and Aluminum Tariffs Hurt American Companies,” March 15, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.tariffsaretaxes.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/3.15_CAMMU%20Press%20Release%20_0.pdf.

[18] Francois, Joseph, Laura M. Baughman, and Daniel Anthony, “‘Trade Discussion’ or ‘Trade War’? The Estimated Impacts of Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum,” Trade Partnership Worldwide LLC, June 5, 2018. Retrieved from: https://tradepartnership.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/232RetaliationPolicyBriefJune5.pdf.

[19] Russ, Kadee, and Lydia Cox, “Will Steel Tariffs put U.S. Jobs at Risk?” Econofact, February 26, 2018. Retrieved from: https://econofact.org/will-steel-tariffs-put-u-s-jobs-at-risk.

[20] U.S. Census Bureau “Quick Facts.” Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/HCN010212.

[21] U.S. Department of Labor and Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, “Charter of the Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations and Trade Policy.” Retrieved from: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/LAC%20Charter%20052020.pdf.

[22] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Union affiliation of employed wage and salary workers by selected characteristics.” Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/union2.t01.htm.

[23] “Labor Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations and Trade Policy (LAC),” Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. Retrieved from: https://ustr.gov/about-us/advisory-committees/labor-advisory-committee-lac.

[24] Anderson, Augustus D., “A Profile of the Retail Workforce: Retail Jobs Among the Most Common Occupations,” U.S. Census Bureau, September 8, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2020/09/profile-of-the-retail-workforce.html.

[25] USITC data for U.S. Harmonized Tariff Schedule chapters 61 and 62, “Articles of apparel and clothing accessories.” Retrieved from: dataweb.usitc.gov.

[26] See for example Finnigan, Ryan, “Rainbow-Collar Jobs? Occupational Segregation by Sexual Orientation in the United States,” SAGE Journals, September 9, 2020. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2378023120954795. See also Tilcsik, András, Michel Anteby, and Carly Knight, Tilcsik, András and Anteby, Michel and Knight, Carly, “Concealable Stigma and Occupational Segregation: Toward a Theory of Gay and Lesbian Occupations,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 2015, 60(3), 446-48, Rotman School of Management Working Paper No. 2653073, August 29, 2015. Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2653073.

[27] Taylor, Lori L., and Jawad Dar, “Fairer Trade, Removing Gender Bias in US Import Taxes,” Mosbacher Institute for Trade, Economics & Public Policy, 2015. Retrieved from: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/153774.

[28] Gailes, Arthur, Tamara Gurevich, Serge Shikher, and Marinos Tsigas, “Gender and Income Inequality in U.S. Tariff Burden,” USITC, August 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/working_papers/gender_tariff_1.html.

[29] President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Special Message to the Congress on Foreign Economic Policy,” March 30, 1954. Retrieved from: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-foreign-economic-policy.

[30] Hufbauer, Gary Clyde, and Euijin Jung, “The high taxpayer cost of ‘saving’ US jobs through ‘Made in America,’” Peterson Institute for International Economics, August 5, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/high-taxpayer-cost-saving-us-jobs-through-made-america.

[31] The White House, “FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Delivers on Made in America Commitments,” March 4, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/03/04/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-delivers-on-made-in-america-commitments/.