(pdf)

If remote work was a growing trend before the pandemic, then COVID-19 kicked it into overdrive. Businesses that would have never considered allowing employees to work remotely were pushed by lockdowns and health concerns to experiment with the work arrangement, and often as not found it to be successful. Though millions of Americans have returned to work in person, Gallup estimates that as of September 2021, just under half of Americans work from home at least sometimes, while a quarter work exclusively from home.

While this shift in attitudes towards remote work has all kinds of implications, one that businesses and employees may not consider is the impact on their tax exposure. During the pandemic, National Taxpayers Union Foundation warned businesses that states could surprise them by using their employees’ remote work to claim income tax nexus for the business.

However, while we have urged states to provide clarity on the issue and warned about the potential for double taxation, the focus so far has largely been on the tax impact remote work can have on individual employees. That’s in large part because that’s where states’ focus has been as well. States worried they’d be revenue-starved due to the pandemic, in particular those that attract commuters from surrounding states, have grasped at the income tax revenue from employees switching to working from home.

But remote work is just one front in a broader state campaign to expand their tax and regulatory powers beyond where their borders end. Given that goal, states can be expected to attempt to exploit remote work to claim the right to as much tax revenue as they can — as a recent statement by the Multistate Tax Commission (MTC) and its subsequent adoption by California’s Franchise Tax Board (FTB) shows.

California’s Tax Nexus Rule

NTUF recently released a report on California’s attempt to circumvent the protections offered to out-of-state businesses by P.L. 86-272, or the Interstate Income Act of 1959. This law prohibits states from taxing the income of out-of-state businesses that have no physical presence in the state besides the solicitation of sales. NTUF’s report focuses primarily on how California uses dubious logic to claim tax revenue from a large number of out-of-state e-retailers with California customers.

The guidance from the FTB largely mirrors a statement by the MTC, a working group of state tax administrators that has been seeking a workaround to P.L. 86-272 for years now. Yet one change that California makes is to describe a business that has an employee working remotely within California performing functions other than those directly related or ancillary to the solicitation of sales as voiding the protections of P.L. 86-272.

Under this standard, the vast majority of remote workers would likely create business income tax nexus for their employer. From data analysts to developers to writers to engineers, all common remote-working positions, each would likely exceed the bounds of “solicitation of sales.”

Impact on Businesses

Consider that for many businesses – particularly smaller ones less savvy about tax preparation – allowing their employees to work remotely may not have been a decision that considered impacts on tax liability. Businesses may have allowed employees to work from home as a favor, or out of concern for their health during the pandemic, all without fully considering the tax implications. After all, the employee is doing the same work for a business — the only difference is that the employee is collaborating with coworkers through the internet rather than being physically in the office.

And even for businesses aware that states may attempt to claim income tax nexus on the basis of remote work, they might not have had a choice. Forced by lockdowns or employee discomfort with in-office work, they may have had to allow employees to work remotely. Going so far as to dictate the locations permissible for performing remote work may have proven infeasible or downright impossible for most businesses.

Alarmingly, California’s rule would apply retroactively to all open tax years, or up to four years in the past. Out-of-state businesses that believed that there was no tax liability change from allowing employees to work remotely in California could be on the hook for California business income taxes, with no way to avoid them.

States use apportionment formulas that take into account some combination of a business’s sales, payroll, and property within that state in order to attribute income properly for business income tax purposes. Many businesses carefully plan out their apportionment to maximize taxable factors in low-tax states and minimize them in high-tax states (such as California).

California, however, is a so-called “single sales factor” state, meaning it weighs only a business’s proportion of sales into the state in its apportionment formula. Practically, this means that out-of-state businesses with a large proportion of sales into California could find a substantial percentage of their profits subjected to California’s relatively high 8.84 percent business income tax rate, instead of Missouri’s 4 percent or North Carolina’s 2.5 percent rate.

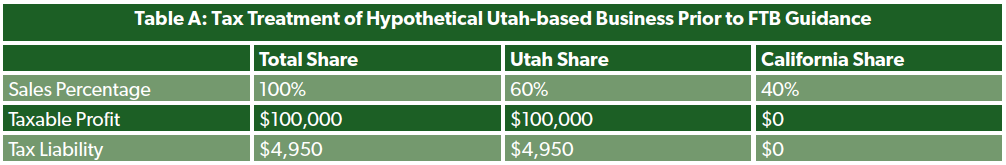

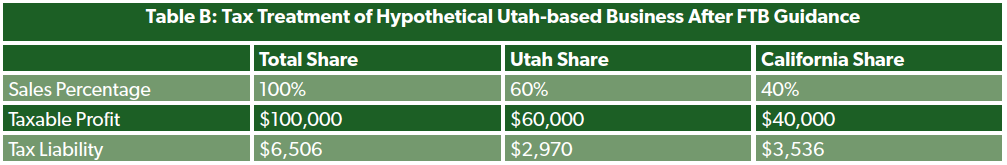

Take the below hypothetical example of an Utah-based e-retail business that currently pays business income taxes solely to Utah, a state with a 4.95 percent corporate income tax rate, but has substantial sales into California and a remote-working employee performing accounting and administrative tasks in the Golden State.

For simplicity’s sake, let us assume that this business sells only to Utah- and California-based customers. California and Utah each use single-factor apportionment methods.

In this example, this hypothetical business, by virtue of a single employee working remotely in California, had its effective tax rate rise from 4.95 percent to 6.51 percent, a percentage increase of over 31.4 percent. Of course, the greater the share of sales sourced from California-based consumers, the higher the effective tax increase would be.

Now, an added wrinkle comes in the form of throwback or throwout rules, which complicate apportionment for business income tax. These rules dictate changes to the numerator or denominator of a tax calculation with the intended purpose of preventing so-called “nowhere income,” which is income that is not subject to business income tax in any state. While a little more than half of states with a corporate income tax utilize one of these means to capture untaxed corporate profits, many do not, including California’s neighbor Arizona.

For a small-to-medium-sized e-retail business in one of these states that previously lacked tax exposure in other states, being subjected to California’s corporate income tax code would mean not just an income tax increase, but also an increase in taxable income. Take a similar hypothetical example, this time for an Arizona-based e-retail business which sells across the country but only has physical presence in Arizona — though it allows an employee to work remotely in California performing accounting and administrative duties.

Arizona allows taxpaying businesses to choose whether to use single-sales factor apportionment or three-factor, double-weighted sales apportionment. Let us assume for simplicity’s sake that this business chooses to use single-factor apportionment for Arizona, a state with a 4.9 percent corporate income tax rate.

Thanks to Arizona’s lack of a throwback rule, this business is paying tax on only 10 percent of its total profits, as Arizona only can tax 10 percent of its profits.

As can be seen here, the business in question would owe over 17 times more in state corporate income taxes simply by virtue of allowing an employee to work remotely in California. Since California has a throwback rule, it is able to include not only sales apportionable to California, but also sales not apportionable anywhere else — effectively entitling it to tax 90 percent of this business’s profits.

Now, one might be tempted to say that this hypothetical business has been getting away with tax avoidance, and would now be properly taxed. There’s a couple problems with this logic, however.

First, under California’s new guidance, this business would be facing an enormous tax increase going back retroactively. That means that not only would it be impossible to avoid the tax assessment, but it would also be impossible to plan for it or build it into a budget. Retroactive tax enforcement is always a bad tax policy practice, but large retroactive tax bills are always more disruptive than small ones.

Second, whatever one thinks about how the 90 percent of profit not taxable under Arizona law should be taxed, determining its taxability on the basis of whether or not a business has a remote-working employee in another state is arbitrary. Though functionally no different than an employee commuting to work from another state, one exposes a business to new tax obligations while the other does not.

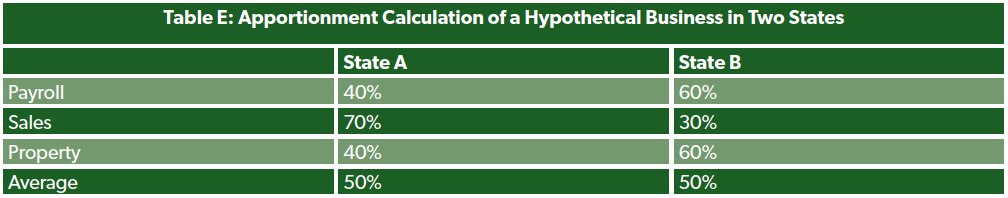

And at an even more basic level, adding more states to a business’s apportionment calculation makes it more likely that a business will be left paying tax on more than 100 percent of its income. Take the below example, illustrating a case where a business has taxable nexus in two states, one of which uses a three-factor apportionment calculation while another uses a single-sales factor calculation. The percentages represent the percentage of each category the business has in each state.

If each state used the same apportionment calculation, this business would owe tax on half of its profits in each individual state. However, because State A uses single-sales factor apportionment, it would claim the right to tax 70 percent of this business’s profits. Meanwhile, State B would claim the right to tax 50 percent, based on its three-factor calculation. In total, this business would owe tax on 120 percent of its profit.

Of course, this is a situation that happens already, and often. But when states are added to a business’s apportionment calculation due to factors they have little to no control over (such as past decisions to allow employees to work remotely when they were unaware it would affect tax liability), it reduces their ability to plan to avoid this kind of overtaxation.

The examples above illustrate ways in which businesses can see tax liability increase as a result of California’s retroactive guidance. But more to the point is the fact that taxable nexus should reflect some sort of connection to the state and the services enjoyed by businesses operating there. From this perspective, does a business with an employee working from home in a state receive anything more from a state’s tax-funded services than a business with an employee who commutes from that state?

It seems most accurate to treat remote work under these circumstances as “digital commute.” After all, the employee is doing essentially just that — traveling to the same office job using technology instead of their feet, public transportation, or a car.

Yet while this designation accurately describes a business that continues to operate a previously in-person employee’s office location, it becomes more complex for an entirely-remote business. After all, if remote workers do not create taxable nexus, then for a business without a physical office location, what state does have the power to tax the business’s income? Such a business could, admittedly, encourage their employees to work remotely then close their office, or move to a state with a less attractive labor market but more favorable tax treatment.

Nevertheless, a solution to this problem that recognizes the nature of remote work cannot be for all 48 states with a corporate income or gross receipts tax to grab a slice of the business income of any business that allows an employee to work remotely in their state. For small businesses used to filing income taxes in just one or a few states, the burden of filing income taxes nationwide would be prohibitive to allowing employees to work remotely. Not only would this lose these employees access to remote work situations, but it would create a competitive imbalance where larger businesses are more able to offer flexible work situations than smaller ones.

Properly utilized, technology helps businesses, making it easier for them to operate and saving them money. However, technology also confuses the application of once-straightforward laws. Unfortunately, tax bureaucrats have every incentive to reinterpret these laws in whatever way maximizes tax revenue.

Conclusion

In our previous report on California’s new income tax guidance, we pointed to the Business Activity Tax Simplification Act (BATSA) introduced in the previous Congress by Rep. Steve Chabot as solving most problems that businesses, particularly e-retail businesses, are likely to face under the new FTB guidance. BATSA would prohibit states from taxing businesses that lack physical presence in the state, set standards for what constitutes “physical presence,” and apply the income tax protections currently enjoyed by sellers of traditional goods and services to digital commerce as well.

Yet the tax treatment of businesses with remote workers is one area that BATSA would not fix. Since California is arguing that a single remote worker constitutes “physical presence” for that worker’s employer, the employer would still likely have taxable nexus under California’s interpretation, even with BATSA in place.

But however Congress chooses to fix the issue, one thing is clear: Congress cannot go on allowing states to ensnare taxpayers in an increasingly unrestrained and overlapping web of tax nexuses.