(pdf)

As Democrats scramble to craft together a $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation bill, the question of pay-fors looms large. One popular potential revenue-raiser among progressives has been, and remains, increases to capital gains taxes.

Capital gains taxes, or the taxes paid on realized appreciation in the value of certain assets, have long been a target for rate increases on the left. But proposed changes to capital gains tax rates thus far floated for inclusion in the budget reconciliation bill are likely to do economic harm outweighing whatever revenue they would raise.

Background

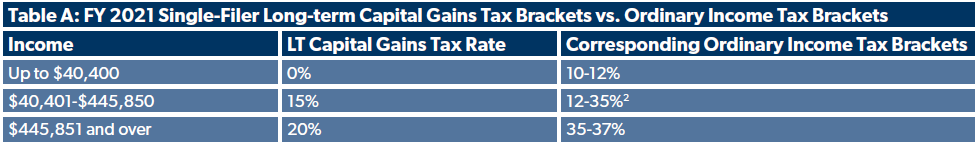

Long-term capital gains and qualified dividends are often discussed as benefiting from a “preferential rate,” as they are taxed at lower rates than other forms of income.[1] Currently, long-term capital gains face just three tax brackets of 0 percent, 15 percent, and 20 percent, as opposed to ordinary income tax brackets which can go as high as 37 percent. Investment income also faces the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) of 3.8 percent for single taxpayers with income above $200,000.

But to call this a “preferential rate” is somewhat of a misnomer. In reality, the lower rate that capital gains income faces is largely in recognition of the fact that capital gains taxes are a form of double taxation.

That’s because most assets subject to capital gains taxes are taxed in other ways as well. Stock appreciation and qualified dividends are subjected to taxation through the corporate income tax code before any benefit is passed on to the taxpayer.

Consider a highly simplified example of the fictional Acme Corporation. In a world without a corporate income tax, Acme would only have to generate $100 in net profits in order for shareholders in the company to receive $100 in capital gains or dividend income. But because of our 21 percent corporate income tax, they in fact have to generate $126.58 in pre-tax profits in order to have $100 in post-tax profits that can be distributed to shareholders. A single shareholder receiving $100 in capital gains or dividend income would then be subject to as much as 23.8 percent in taxes, leaving just $76.20 in post-tax income from the original $126.58 in pre-tax profits.[2] The capital income that finally reaches an individual in this example was subjected to a total of 39.8 percent in taxes, illustrating the double-taxation effect that can push actual tax rates on capital income higher than the current top individual income tax rate of 37 percent.

Therefore, while it is true that long-term capital gains and qualified dividends face lower tax rates than ordinary income, it is also true that they face a layer of taxation that most ordinary income does not. A tax code that taxed these forms of income the same as ordinary income would actually be disfavoring them. At the top rate of 37 percent, our shareholder’s post-tax income drops to just $63 from the original $126.58 in Acme’s pre-tax profit, which equates to a total tax rate of 50.2 percent.

With this in mind, let’s take a look at some of the proposals on the table to alter the tax treatment of capital gains.

Proposed Changes to Capital Gains Taxation

Taxing Capital Gains As Ordinary Income

President Biden has publicly supported taxing capital gains as ordinary income since he was on the campaign trail. Combined with his proposal, also likely to be included in the upcoming reconciliation bill, to raise the top income tax bracket to 39.6 percent, as well as the 3.8 percent NIIT, long-term capital gains could face a top tax rate of 43.4 percent at the federal level. In our Acme example, this would convert to a total tax rate of 55.3 percent on qualified capital gains or dividend income associated with the company’s pre-tax profits.

The previous section addressed the “tax fairness” argument often made to justify capital gains tax increases, but such a significant tax hike on investment would likely create serious economic harms. We know from past capital gains tax increases that investors tend to rush to realize their gains when a hike to capital gains taxes is imminent, then hold onto them once tax hikes kick in. Drastic changes to capital gains tax rates create drastic distortions to taxpayer behavior.

Another problem is one of competitiveness. Even before factoring in the average state capital gains tax rate of 5.2 percent, a 43.4 percent capital gains tax rate would be the highest in the OECD, and the highest rate in the United States in about a century. Even under current law, the American capital gains “preferential rate” is still relatively high compared to OECD countries.

We know that higher capital gains tax rates discourage saving and investment, the drivers of productivity and wage growth. The United States would be placing itself at an economic disadvantage compared to other developed countries by disincentivizing these beneficial economic activities.

Ending the Step-Up in Basis

The step-up in basis received special attention recently with the release of a report by investigative outlet ProPublica based on the tax records of thousands of wealthy individuals that ProPublica somehow managed to access. The report, which NTUF responded to here and here, alleged that the wealthy manage to effectively avoid taxes by using the step-up in basis to pass on assets to heirs and zero out any taxable capital gains.

The step-up in basis allows heirs to “reset” the tax basis of inherited assets, meaning that were they later to sell an inherited asset they would pay capital gains taxes based on the value of the asset when it was inherited, not when it was purchased by the decedent.

Take the example of a person who buys stock at a value of $10 a share in 1970. Upon their death in 2000, the stock was worth $30 per share. Should this person’s heir choose to sell a share in 2005 when the stock has appreciated in value to $35, they would have realized only a $5 capital gain (from $30 to $35) since the basis was “stepped up” in 2000, rather than a $25 capital gain if the basis was still its 1970 price.

The step-up in basis is by no means a shining example of ideal tax policy. On the other hand, it exists in large part to shield taxpayers from other flawed portions of the tax code.

One such flaw is the lack of indexing for inflation. In the above example, the stock share’s growth has actually not kept up with the pace of inflation, since $10 in 1970 was worth about $45 in 2000. Thus, the $25 “appreciation” in the stock price in the 30 years between 1970-2000 was in fact a real loss of $20 per share, after accounting for inflation. The step-up in basis in this instance shielded the heir from having to pay a tax bill on an asset that, though it nominally appreciated in value, is actually worth less in real terms than it was when it was purchased.

The step-up in basis also acts as a bulwark against the death tax. When cash-poor heirs inherit a substantial estate, such as a family business, they can be forced to sell off significant assets just to pay their family member’s death tax bill. In the absence of the step-up in basis, the assets sold to pay a tax bill would also be subject to capital gains tax on the appreciation in value. The death tax is unfair enough as it is without compounding the burden by taxing heirs on assets they sell to pay another tax.

Another reason to be skeptical of step-up in basis repeal is more mundane — decedents can’t always be counted upon to keep good records, especially going back decades. The step-up in basis protects heirs from being held responsible for locating records that could go back to before they were even born, and limits the extent to which the Internal Revenue Service is tasked with the time-consuming and expensive work of valuing long-held assets for tax purposes. The death tax is an administrative nightmare in large part due to these valuation challenges, and step-up in basis helps to reduce the odds that capital gains taxation becomes a similar administrative disaster.

Deemed Realizations

Another proposal which would effectively end the step-up in basis in a more roundabout way would be to impose deemed realizations on gains above $1 million when assets are gifted, the owner of the asset dies, or the asset has not been realized in over 90 years. This would take place in concert with other proposals to tax capital gains as income.

Aside from the moral issues entailed in forcing taxpayers in some cases to pay tax on long-held assets despite there being no sale and no transfer in ownership, such a proposal would likely be administratively unworkable. As the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) warns, a system of deemed realizations may require partial owners of assets to value their proportionate share when they lack necessary information, and even the legal right to acquire it.

Moreover, it could also end up pushing people out of the country. One of the major consequences of expatriation is that expatriates are required to pay capital gains taxes on asset appreciation prior to leaving. A system of deemed realization for wealthy individuals who stay would make this requirement largely redundant. Combined with other proposals contained within which send a clear message that the wealthy are only likely to be targeted more and more for additional taxation, this may provide the push to send some wealthy Americans elsewhere.

Establishing a Mark-to-Market System

Legislators such as Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) have long proposed to annually tax unrealized capital gains as a way to raise revenue, minimize taxpayer sensitivity to capital gains tax changes, and open the door to taxing wealth. Wyden has more recently proposed legislation to be considered for the reconciliation bill that would establish systems to tax unrealized capital gains (known as “mark-to-market” taxation) for derivatives and carried interest, perhaps as a precursor to broader mark-to-market proposals.

Mark-to-market taxation would be a form of wealth tax, as it would assess a tax on assets that are held but not sold. As such, depending on the scope, it would suffer from most of the same drawbacks as wealth taxes.

The first and most obvious problem is administrative. While some assets (such as shares of publicly-traded companies) are relatively easy to value at any given moment, others (such as shares of privately-held businesses, or real property like art) are not. Most developed countries have avoided attempting to tax wealth in large part because it is monstrously difficult to do so.

At a time when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has launched a full-court press to beg Congress for a funding bailout, any mark-to-market system would require the IRS to massively expand its administrative capabilities.

There are other technical issues as well. It’s not uncommon for entrepreneurs and start-up owners to hold assets which are worth a great deal on paper, but at the same to have few liquid assets in hand. Expecting these individuals to pay large tax bills based on the theoretical value of their unrealized assets could force them to sell off parts of their businesses before they intended to just to pay a tax bill.

There’s also the question of capital losses. While proponents of mark-to-market taxation relish the thought of huge revenue windfalls when asset prices are rising, it is not uncommon to see massive on-paper losses in lean economic times, particularly among the wealthy that such a system would target. Volatile assets can spike in value one year then crater the next, and any fair tax system would have to allow taxpayers to recoup losses just the same as they’re forced to pay tax on gains. Otherwise, a mark-to-market system would be a classic “Heads I win, tails you lose” scenario for revenue agents, with huge tax burdens on the upside and no loss allowance on the downside.

Increasing Taxes on Carried Interest

General partners of hedge funds or private equity funds are often compensated through what is known as “carried interest,” or a commission on returns. Because the commission represents dollars that are subject to investment risk, it is taxed as a capital gain. Carried interest is also traditionally kept invested in the fund for years until the partner cashes out — in other words, the partner’s “interest” in the fund is “carried” over year after year.

Taxation of carried interest as capital gains is often referred to as a “loophole,” as though it exists in the tax code by accident. It does not. It is an appropriate classification of income, since the dollars are subject to investment risk and represent value for the “sweat equity” provided by fund managers. And Congress already limited the scope of carried interest in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, requiring assets to be held for more than three years to qualify for treatment as investment income. Further restricting or outright eliminating the ability to treat carried interest as investment income would represent a substantial tax increase on the over 4 million partnerships in the United States, arbitrarily targeting them over other types of investment.

Nevertheless, proposals to close the so-called “carried interest loophole” have surfaced in budget negotiations. The aforementioned proposal by Sen. Wyden would go one step further than taxing carried interest realizations as ordinary income, subjecting them also to mark-to-market taxes on an annual basis.

By restricting and penalizing investment, increasing taxes on carried interest could entail substantial economic impacts. A recent report by the Chamber of Commerce estimates that proposed tax increases to carried interest would cost 4.9 million jobs within 5 years and cause pension funds to lose up to $3 billion annually.

Conclusion

To legislators desperate for pay-fors to ameliorate a truly enormous $3.5 trillion spending agenda, capital gains may appear to be a tempting target. Yet proposals to increase taxes on capital gains would do more harm than good, and would entail gargantuan administrative challenges.

After a pandemic spending surge which is already set to see the national debt increase by over $6 trillion over just two years, legislators should be thinking about how to rein in spending, not pursuing never-ending tax-and-spend schemes. The last thing the country can afford right now is to have the economy run into the ground by poorly-considered tax hikes.

[1] Long-term capital gains are distinct from short-term capital gains, which are taxed at the same rates as ordinary income. To qualify for the lower long-term capital gains tax rate, an asset must be held for over a year before any gain is realized. Dividends are similar — dividends from an asset held for a year or less are taxed as ordinary income, while dividends from an asset held for more than a year are known as qualified dividends and taxed at lower rates.

[2] Note again that this is a highly simplified example, not taking into account corporate tax deductions or state corporate taxes.