(pdf)

Introduction

The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) included nearly $80 billion in new funding for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Most of the money is intended to increase tax enforcement and reduce the “tax gap.” The tax gap is a measure of the difference between what people and businesses actually pay in taxes versus how much the IRS thinks they really owe. Whether it happens through innocent mistakes, misunderstandings of the laws, or willful tax fraud, the Department of the Treasury estimates that people underpay their taxes by $600 billion per year (This estimate itself is in dispute, a subject covered more in a May 2021 NTU Foundation policy paper.).

Now that the IRA is law, there are concerns regarding how the $80 billion for the IRS will be used, who will feel the brunt of increased audits and other new enforcement efforts, how many new “agents” will be hired with the money, and how much revenue will be raised. This paper explores many of the claims surrounding the expanded IRS.

87,000 Or Not: How Many New Staff is the IRS Hiring?

After passage of the IRA, critics of the tax enforcement measure warned that taxpayers would face intensified scrutiny from an IRS supersized with nearly 87,000 new staff. The figure is from an official government report from May 2021 when the Biden administration was pushing for passage of the original “Build Back Better” plan. The Treasury Department, which oversees the IRS, published The American Families Plan Tax Compliance Plan, laying out the case for expanding the IRS and significantly increasing enforcement activities. The report includes a table showing that they would use the funding boost to add precisely 86,852 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees over the next decade. This would more than double the size of its current workforce: the IRS employed 78,661 FTE positions in FY 2021 and 79,808 during FY 2022. Below is the table as it appeared in the Treasury report.

However, many news outlets pushed back at the use of this figure and disputed that these FTEs would all be new hires, including the following:

Yahoo News wrote, “Republicans are taking that figure from a chart buried in a report the Treasury Department issued last year.”

Reuters used the same phrasing in its reporting, “The 87,000 figure does exist, buried within a May 2021 Treasury Department report.”

PolitiFact also acknowledged the origin of the number but wrote “it isn’t set in stone.”

Grid News called the 87,000 number an “obscure factoid.”

If the figure was “buried,” does that mean that Treasury was trying to hide it or that people outside of the administration should not cite it? There is little reason that taxpayers should not take at face value what the administration said they would do.

Natasha Sarin, the Treasury Department’s counselor for tax policy and implementation, has since argued that the net number of hires would be much less than 87,000 because the funding would be used to replace 50,000 workers who are expected to leave the agency over the next few years. Media fact-checkers echoed this line of argument. PolitiFact wrote, “The hires would be phased in over time and come as the agency braces for a projected loss of 50,000 employees over the next five or six years largely because of retirements.”

Sarin’s statement has led to some confused reporting, such as the tangled web of numbers featured in this syndicated news article: “About 80,000 people work for the IRS today. Add another 87,000 employees and that means the IRS is set to double its staff over the next 10 years, right? Not quite. Enforcement staffing has fallen by 30 percent since 2010 and the agency has lost approximately 50,000 agents over the past five years due to attrition, according to the IRS.” Time Magazine’s particularly misguided account observed that “In all, the IRS might net roughly 20,000 to 30,000 more employees from the new funding.”

However, Sarin’s claim contradicts a sentence in Treasury’s tax compliance agenda that explicitly indicated the purpose of the new funding was to steadily and significantly increase the IRS’s workforce: “Because the expansion in the IRS’s budget is phased in over a 10-year horizon, each year the IRS’s workforce should grow by no more than a manageable 15 percent.”

It is unclear exactly what Treasury based its 15 percent growth rate on, but assuming that the IRS were to grow annually at 15 percent of 2021 levels by hiring approximately 11,800 FTEs per year, over ten years this would include the 87,000 new hires and accommodate replacement of 31,000 FTEs otherwise lost through attrition. To reiterate, Treasury’s compliance agenda, which is not “buried” but is a careful statement of proposed policy, accounts for both attrition and new hires. There is no “net” figure in this plan that results in only 20,000, or 30,000, or some similarly “small” number of new FTEs.

Furthermore, attrition is a constant in the IRS’s workforce. In the FY 2023 budget justification, IRS Commissioner Chuck Rettig wrote that the agency expects over 60 percent of its employees will retire within the next six years. Based on recently reported hiring levels, this amounts to 8,700 employees per year and a total of 47,000 employees leaving the IRS over the time period (a figure which was probably the basis for Sarin’s 50,000 estimate). There was no mention of overall attrition rates in the IRS’s budget justifications over the recent previous years (except a note in 2019 that it planned to replace attrition and hire approximately 2,000 additional enforcement personnel) but the Journal of Accountancy reports that the IRS average annual attrition rate is 7.3 percent.

Even before the passage of the IRA, the IRS was boosted with supplemental funding provided through the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan Act. Both of these laws tasked the IRS with additional administrative duties to oversee expanded tax credits (some of which were to be paid in advance) and to distribute economic recovery rebates to millions of taxpayers. Generally, the IRS’s workforce is funded through the regular annual appropriations process.

For the upcoming FY 2023, the Biden administration requested $14.1 billion in funding for the IRS, nearly 11 percent more than the FY2022 enacted amount. Including an estimated $1.1 billion in miscellaneous resources, the IRS’s FY2023 operating budget would total $15.2 billion. With that funding through the regular appropriations process, the agency proposed to reach an FTE level of 86,289 in 2023, a net 6,481 increase over FY 2022.

The White House’s budget office projects that the IRS’s annual regular operating budget will continue to grow over the next several years. As part of the annual budget release, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) publishes a spreadsheet of outlays for agencies and programs across the federal government. This includes historical data since 1962, the requested budget levels for the next fiscal year, and a projection of regular budgetary resources for the next four years after that. For the IRS’s operational budget, OMB projects outlays growing to $15.7 billion in 2027, presumably to build on the primary goal of “building back a strong workforce,” noted in Rettig’s FY 2023 budget justification. In the absence of the IRA’s supplemental $80 billion, the IRS would have continued the process of replacing and expanding its workforce.

For additional evidence that the IRS was addressing attrition and growing its staff level, Commissioner Rettig testified in a May 2022 Senate committee hearing that, “The full fiscal year 2022 President’s Budget request would have allowed us to maintain current staffing levels and fund 4,200 additional full-time equivalent employees." That budget request was for $14.25 billion and would have increased the number of FTEs from 76,202 to 80,717. By the time Congress completed the FY 2022 budget process, the IRS ended up with $13.98 billion in total budgetary resources, a little less than they requested, including $11.92 billion from the FY 2022 appropriations and an additional $2.05 billion in other budgetary resources. Again, the regular budget and appropriations process has been addressing the agency’s attrition problem, albeit imperfectly, for several years.

Sarin has said that agency officials don’t yet know how large the workforce would ultimately be with the funding hike, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has tasked the IRS to come up with a plan on how the funding will be used. If the administration is now pursuing a different path, it might be because of widespread concerns raised about an expanded and more powerful IRS.

The Department of Treasury could easily clear up the matter by producing a table showing its projection of IRS workforce levels, accounting for annual attrition and new hires. In the absence of any additional data showing the projected net workforce baseline, taxpayers should conclude that the Biden administration plans to expand the IRS’s workforce by bringing on new employees, including auditors, revenue agents, revenue officers, investigators and (based on the congressionally directed allocation of the $80 billion) a notably smaller number of customer service and support employees.

What is the Right Size for the IRS?

The administration and IRS officials have argued that the IRS workforce has been significantly reduced as a result of budget cuts. The agency’s budget was indeed reduced in the 2010s, partly in reaction to revelations that some (primarily conservative) nonprofit organizations were denied tax-exempt status in the run up to a federal election. Lois Lerner, who headed the division approving these tax-exempt status applications, became the lightning rod for subsequent reforms and budgetary decisions. Investigations uncovered that the emails and computer data of the principal personnel involved in the controversy had been erased or destroyed, leading to even greater ire among conservative appropriators in Congress. As a result of this budget tightening, Treasury’s compliance agenda notes that the IRS enforcement budget decreased by 15 percent between 2010 and 2021 period, resulting in a 20 percent decline in the IRS workforce.

IRS’s Annual Budget

The IRS’s operating budget is a blend of annual appropriations and miscellaneous resources, including reimbursement for services provided to other federal agencies, offsetting collections, user fees, and unobligated funding carried over from previous years. The table below shows the IRS’s annual budgets since 1962, based on OMB data.

IRS Workforce Levels

The table below shows the size of the IRS workforce since 1962. The data through 1986 is based on average annual employment levels reported in the 1988 Data Book. Data since 1987 reflect the total number of FTEs listed in each of the annual editions of the IRS Data Book.

IRS employment peaked in 1991 with over 138,000 employees, which included over 29,000 seasonal employees brought on to assist with processing returns. Workforce levels since then have generally decreased in line with the rise of electronic filing and increased automation of IRS administrative processes.

Unfortunately, the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) found that the IRS could do a better job of automating tasks and maximizing efficiencies. Still, with technological progress and agency reform, the IRS should be able to provide more services with fewer taxpayer dollars.

Modernization of IRS systems and technology has always been a part of this equation, especially as it relates to labor costs. To give just one example, the 1997 report of the National Commission on Restructuring the IRS, which later became the basis for a landmark reform law, explicitly delineated several advantages of encouraging greater e-filing of returns:

“In addition to labor, overhead, and management costs to operate the returns processing pipeline, there are other cost reductions that could be realized with an increase in electronic filing, such as the following:

Heavy dependence on manual labor creates additional recruitment and training costs for IRS since it causes spike demands for low-cost labor that is not always available.

Facility and physical handling equipment associated with paper filing is much higher than that used for electronic returns.

After the data is manually entered into the database, the paper return is archived. Storage costs for paper returns are higher than those for electronic returns. Any subsequent need to access a return, such as an examination or collection, or requests by taxpayers for a copy of the return, results in retrieval costs as well.”

NTUF laid out a package of reforms needed at the IRS to improve its operations and become more efficient, including reducing barriers to electronic filing, bringing in private sector experts by reconstituting and revitalizing the IRS Oversight Board, and implementing Government Accountability Office recommendations for the IRS to more effectively make use of its existing funding. In addition, simplifying the tax code not only reduces taxpayers’ compliance burden, but it also makes it easier for the IRS to administer with a smaller workforce.

Will the New Employees Work on Enforcement or Taxpayer Services?

Fact-checkers have also pushed back on the 87,000 new IRS “agents” data point because some of the new hires would also work on taxpayer services, which have been languishing at the agency. While it is true that some resources will be devoted to improving services provided to taxpayers, it represents a small portion of the $80 billion. After all, the administration’s plan was called the “Tax Compliance Agenda” and not the “Taxpayers Assistance Agenda.”

It is quite true that many techniques to improve tax compliance need not involve direct enforcement such as audits or criminal investigations. Returning once again to the IRS Restructuring Commission’s 1997 report, Commissioner Ernest Dronenburg, a former leader with California’s State Board of Equalization, observed that “a .5 percent increase in voluntary compliance resulting from taxpayer education and changing attitudes would increase revenue in my state by over $400 million annually. Conversely, doubling our current audit coverage from 3% to 6% would produce less than half that amount.”

Nonetheless, Treasury’s chart indicates that the additional employees would effectively yield higher tax revenues through the combination of additional direct revenue from taxpayers who are not currently in compliance with tax law, and through “revenue protected” program integrity efforts such as reducing improperly claimed tax credits. Given the return on investments figure calculated by the administration, taxpayers could reasonably conclude that the bulk of these new IRS employees would be involved in enforcement rather than taxpayer assistance.

The text of the document also heavily stresses compliance. Below is a chart showing the frequency of use of certain words and phrases in the document, illustrating the focus on compliance over services. “Compliance” was used 120 times throughout the document (including the title of the report repeated 23 times). Meanwhile, the word “assistance” was used just twice. The word “services” appears eight times in the agenda, including two appearances in the phrase “taxpayer services.”

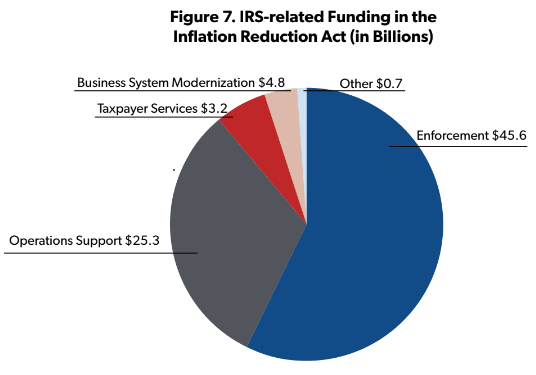

The focus on compliance is also clearly evident in the distribution of the IRA’s $80 billion in funding, illustrated in the chart below. Over half of the amount goes to enforcement while just four percent of the amount goes to taxpayer services. The amounts under “other” include $400 million for the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, $153 million to the U.S. Tax Court, $105 million for Treasury’s Office of Tax Policy to promulgate regulations, and $50 million to Treasury for IRS oversight.

Increased Enforcement Will Not Just Impact “Tax Cheats”

President Biden and Treasury Secretary Yellen had promised that no one earning less than $400,000 per year would be impacted by the new enforcement measures, and that new audits will only target a small class of wealthy taxpayers who are not paying their “fair share.”

The number of millionaires being audited has dropped off significantly since 2015, when nearly 40,000 millionaire returns were reviewed. In 2020, 11,000 millionaires were audited, and the figure rose to nearly 14,000 in 2021. This number will continue to rise with the new emphasis on enforcement, but additional taxpayers further down the income ladder will likely be swept up in the IRS’s net. In the wake of the IRA’s enactment, Republicans and other critics of the IRS expansion warned that new revenue agents will inevitably target the middle class.

Treasury’s Sarin told Reuters in response, “The speed and voracity with which (Republicans) are coming at this is really a testament to how important these resources are going to be - because there are many wealthy tax evaders that stand to lose a lot.” A college professor and columnist separately argued that taxpayers only need to worry about a supercharged IRS if they are “tax cheats.” And on NBC’s Meet the Press, Chuck Todd said, to the delight of his fellow panelists, “ … you know my answer to people afraid of more IRS agents is well, you know, then don’t cheat on your taxes.” This type of argument ignores the disproportionate impact that IRS enforcement activities can have on low- and middle-income taxpayers, as well as small business owners, who don’t have the resources to challenge enforcement claims. These taxpayers may also ultimately be innocent of what the IRS is charging, or may have made an honest mistake on their tax returns.

In reality, many additional taxpayers will likely be affected by stepped-up enforcement efforts. The IRS is expected to focus more scrutiny on the self-employed, whether as sole proprietors, limited liability corporations, or S-corps. Moreover, the IRS collects mountains of data from employers, contractors, and financial institutions and feeds them into the IRS databases. Any discrepancy among the data automatically generates tens of millions of notices annually that are mailed out to taxpayers. The more data the IRS collects, the more opportunities it will find to claim that taxpayers are underpaying.

It costs money and time for the IRS to conduct audits, and when the IRS determinations are challenged, the court cases can drag on for years. Targeting complicated tax arrangements of wealthy individuals and businesses can be more difficult because they have resources to obtain the best tax attorneys. For households making $75,000 or less, the IRS makes $10 for every $1 it spends in the collection process, and 50 percent of IRS audits fall on these households. Low-income earners are audited at five times the rate of all other taxpayers, due in part to the high record of improper payments for wrongly or incorrectly claimed refundable tax credits. Also, they are generally easier tax overpayments to reclaim because the taxpayers are less likely to contest the IRS.

One reason why people suspect that the IRS tax enforcement will focus on the middle class is that the Biden administration initially included a proposal to give the IRS access to nearly everyone’s financial transactions. The plan was to require banks and other financial institutions to report all transactions from any account with at least $600 in annual activity to the IRS. Because of its far-reaching implications on nearly all taxpayers, the proposed threshold was raised to $10,000, but eventually the idea was dropped. Separately, the American Rescue Plan Act lowered the 1099-K reporting threshold from $20,000 and 200 financial transactions to just $600 with no limit on the number of transactions. This was projected by CBO to increase tax receipts by $7.7 billion over ten years, but the substantially lower threshold is set to cause significant headaches for taxpayers who use payment services like Venmo or use eBay as an ongoing online garage sale.

Some households will, in theory, be protected by Treasury Secretary Yellen’s directive that the additional resources provided in IRA “shall not be used to increase the share of small business or households below the $400,000 threshold that are audited relative to historical levels.”

The order does raise some confusion for several reasons. For one, Yellen did not indicate what “historical levels” would be the basis for further audits. For example, in 2011, just prior to a multi-year drop in IRS funding, the examination coverage rate of individual returns reporting $75,000-$100,000 of positive income was five times greater than the 0.1 percent coverage rate reported in 2019.

Other questions include:

Who gets to define $400,000? Does that amount represent Adjusted Gross Income, Modified Adjusted Gross Income, or Taxable Income? Is it what a taxpayer reports on their return for the year the IRS wishes to conduct an examination, or is it what the IRS believes the taxpayer’s taxable income ought to be after proposed adjustments? If the latter, greater numbers of Americans than advertised will be subject to scrutiny, perhaps to no avail.

Does this directive create a “marriage penalty,” in the sense that the IRS could investigate a single taxpayer’s return reporting above $400,000, but could also look into a joint return where each taxpayer earns $200,000? Dual-earner households in large cities – many of which are located in blue states – could be surprised to find themselves under the microscope.

What year will govern the audit decision – the year of the return under examination, or the taxpayer’s present circumstances? A business owner who earned $500,000 during the good times of 2019 might be shocked to get an audit notice next year if she finds herself struggling with half that cash flow today. In fact, high-income tax returns are also among the most volatile in reporting year over year incomes.

What happens if the directive is disobeyed or unintentionally violated? The Secretary’s ability to impound funds is highly limited. And if “accidents” happen, how can a taxpayer possibly be made whole? A Treasury directive does not carry the force of law in court, and regardless, no outside entity will be monitoring IRS audit rates in real time.

Do these concerns amount to parsing words? Perhaps, but the operation of the entire tax system often amounts to this very exercise, as Congress proves with myriad technical corrections to various tax laws. For its part, the IRS has frequently denied taxpayer appeals, pursued exotic enforcement and litigation strategies, issued absurd rules, and reversed its own mind, based on interpretations (and contortions) of a few words. In this environment, taxpayers are entirely justified in wondering how exactly Secretary Yellen’s directive will translate to IRS personnel on the ground.

Beyond these considerations, Secretary Yellen is asking the IRS to do something that is neither practical nor transparent. Money is fungible – nothing the IRS receives in annual appropriations, over and above the IRA funds, would be subject to the $400,000 taxpayer income limitation. The Service could also simply request from Congress, or to a more limited degree, redirect, more funds from what it would otherwise normally spend on high-income enforcement activities toward those lower on the scale. Furthermore, neither Secretary Yellen nor Congress demanded that any kind of public accounting be kept on how enforcement dollars will be used against certain types and classes of taxpayers. Additional monies in the IRA to the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration could be employed for such purposes, but here again, the legislation is silent on where TIGTA is supposed to look.

For definitional reasons above and others these vague protections would have been better implemented through the force of law, but Senate Finance Committee Chair Mike Crapo’s (R-ID) attempt to amend the IRA to prevent the IRS from using any of the funds to audit taxpayers with taxable incomes below $400,000 was defeated on a party line vote. However, Secretary Yellen’s directive did confirm that Biden’s pledge on increased tax enforcement against the middle class would have been broken. CBO revised its revenue estimate from tax enforcement downward by $20 billion, taking the official directive into account.

Over the decades, there have been far too many examples of poor treatment of taxpayers by heavy-handed IRS actions. Among the most egregious include the case of Tom Treadway, who lost his business after a bogus $247,000 tax assessment that was later thrown out on appeal ( the IRS also raided his girlfriend’s bank account), and Alex Council, who lost his business and took his own life after a badly handled IRS audit that was eventually overturned. Reforms and strong oversight will be necessary to guarantee that taxpayers are protected as the IRS cranks up tax enforcement.

New Revenues May Fall Short of Estimates

IRA’s proponents had counted on new tax collections to reduce the deficit. However, the estimate of the new revenues that will be collected via enforcement has already been reduced, and there are several factors that could mean that receipts will fall short of the revised estimate.

The compliance agenda had estimated that its plan would lead to $316 billion in additional tax revenue collected over the decade. This estimate also included the financial reporting for accounts with at least $600 in annual activity that was eventually withdrawn. Estimates from the executive branch about their own proposals tend to be overly optimistic, which is one reason that Congress established its own scorekeeping agency, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Last November, CBO estimated that the earlier version of the reconciliation package which contained the same IRS funding increases, would lead to $207.2 billion in new revenue. CBO estimated that IRA’s tax enforcement provisions would generate $203.7 billion over the decade. A few weeks after passage, the agency announced it had lowered the estimate of revenues from enforcement by a total of $23 billion to $180.4 billion.

As noted above, most of the change was due to Yellen’s directive limiting audits on those earning less than $400,000 – essentially an admission that somehow part of the funding would have an impact on taxpayers below Secretary Yellen’s threshold. In addition, the final version of the IRA dropped a provision granting the IRS expedited hiring authority. In the absence of that authority, it will take longer to onboard and train new employees, reducing the level of expected collections.

As inflation leads to higher cost-of-living adjustments for federal workforces, the IRS may not be able to hire as many people with the funding provided (though the number of additional FTEs would still be much larger than mainstream media estimates). This would further undermine revenue estimates.

In addition to IRS’s ability to hire and train new staff, other points of uncertainty noted by CBO include, “the composition and productivity of the additional audits and other enforcement actions undertaken by the IRS, changes in taxpayers’ behavior in response to greater IRS enforcement, and the effect of increased IRS spending in areas other than enforcement (such as technology).”

The success of an audit by the IRS is not guaranteed. Challenging the IRS can be costly and drag on for a long period of time, but the agency is by no means always successful in securing judgments against those it accuses of fraud. NTUF previously compiled a list of news articles where the IRS had taken an overaggressive position against taxpayers and ultimately lost in court.

The IRS also needs to do a better job of identifying potentially non-compliant taxpayers. Through various auditing programs, the IRS will use comparative analysis to select taxpayers the agency believes may be underreporting income. But a high percentage of those audits yield no net change in the reported income tax liability.

Earlier this year, a review of audits of partnerships saw high no-change rates, ranging from 78 percent to 90 percent from 2017 through 2019. TIGTA also reported in 2020 that nearly half of IRS examinations of large businesses were closed with no change to the tax return. The program is supposed to select cases for review where the IRS thinks that enforcement efforts will close the tax gap. TIGTA estimated that these no-change examinations potentially cost the IRS $23 million and consumed over 200 administrative hours. This also imposes unnecessary burdens on businesses who are in compliance with tax laws. The IRS taxpayer burden model calculates that large businesses spent an average of 895 hours per return, but those with income over $100 million spent an average of 5,083 per return. These estimates do not include the time incurred through the examination process.

Conclusion

Despite assurances from the administration, the IRS will be much larger than it is today and will engage in more aggressive enforcement strategies with the IRA funding boost. Over the course of its history, there are recurring examples of abusive treatment of taxpayers. Safeguards and strong oversight will be needed to protect taxpayer rights.