(pdf)

A bill passed recently by the House of Representatives would increase some veterans benefits through 2027 by $19 million. On paper, this spending increase is “paid for” over the decade because the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) scores the bill as reducing the deficit by $1 million. The “pay for” is extending a veterans mortgage loan fee for nine additional days in FY 2031, and using the funds for that new spending instead of its intended purpose of being a reserve against veterans’ mortgage defaults.

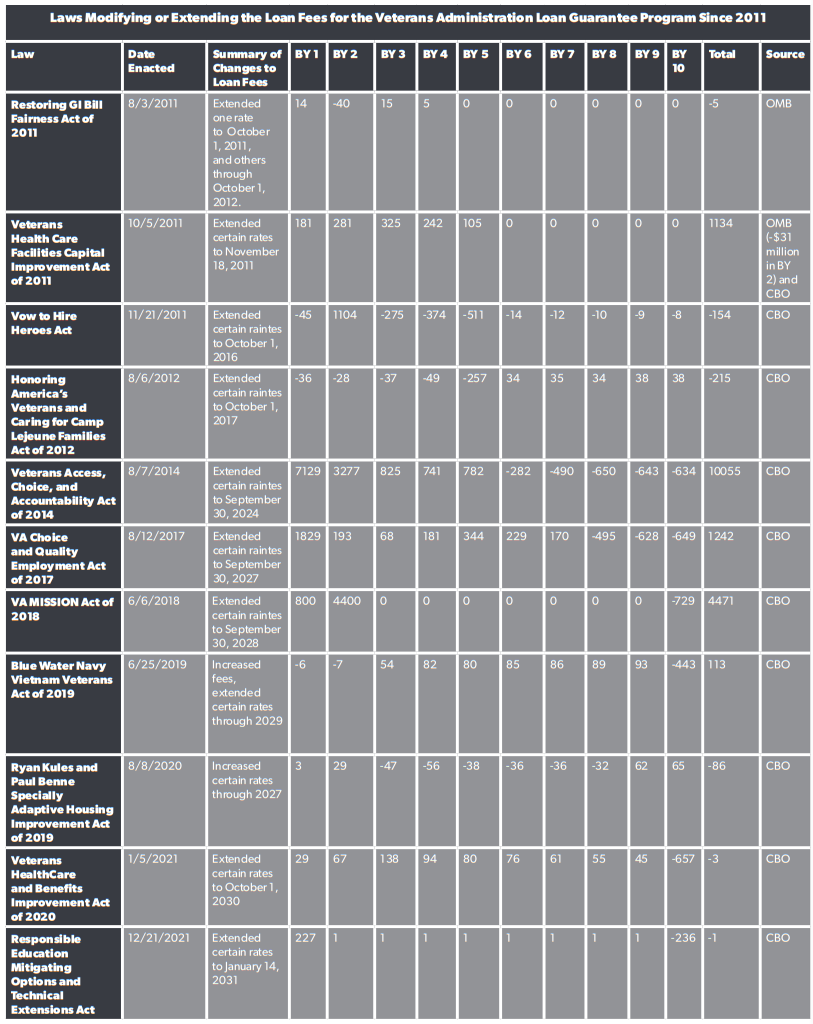

This fee was established in the 1980s to offset the subsidy cost of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) home loan guarantee program when a borrower defaults on a loan. Increasingly over the last decade, lawmakers have either extended or increased the loan rates several years out in the future as a way to offset other new spending.

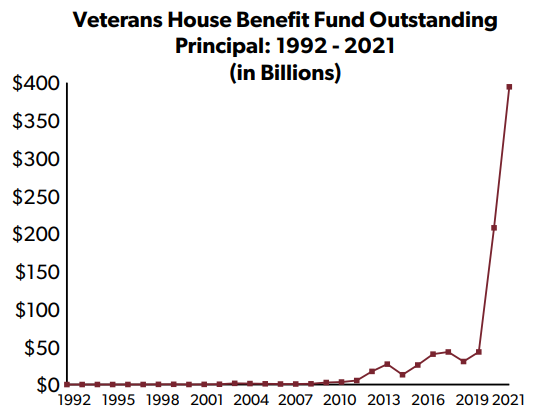

This practice is especially dangerous now, because the risks of the VA loan guarantee program have significantly increased recently. The total outstanding principal supported through this guarantee has skyrocketed from $87 million in 2000 to $394 billion today— with the vast majority of that jump occuring in the last few years. Congress should be looking for ways to safeguard taxpayers from risky loans rather than siphoning offsets to mask chronic overspending.

Background on the VA Loan Guarantee Program

The VA home loan guarantee program was established in 1944 as an alternative to cash bonuses provided to servicemembers during World War II. Since then the program has been made available to active duty members with minimum length-of-service requirements, honorably-discharged veterans (including those who served in the National Guard or Reserves), and certain surviving spouses. Through the program, the VA guarantees lenders a portion of losses in the event of default. This allows the borrower to obtain more favorable mortgage terms.

Typically, VA guarantees the first 25 percent of losses to lenders for mortgages with an original balance that is greater than $144,000. However, the maximum guarantee varies depending on the value of the mortgage and other factors. Unlike loan guarantees from the Federal Housing Administration, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac, there is no down payment requirement through the VA's program.

Background on the Fees

Fees were not established until passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1982. The current fee schedule specifies rates for 22 different conditions, with rates varying depending on when the mortgage was issued, whether there was a down payment, among other factors. For example, the fee for a loan to purchase or construct a dwelling with zero down payment that closed between October 1, 2004 and January 1, 2020 is set at 2.15 percent for active duty service members and veterans. The same type of loan closed on or after January 1, 2020, and before April 7, 2023 has a fee set at 2.3 percent. In 2021, the fees ranged from 0.5 to 3.6 percent. Certain veterans are exempt from the fee. CBO found that about half of all borrowers in 2021 were exempt from the fee for a service-related disability or for spouses of veterans who died in service.

The VA Loan Guarantee Program Budget

In 2021, the program had administrative costs of $204 million and employed 768 full-time equivalent (FTE) personnel. The Analytical Perspectives section of the FY 2023 budget shows that VA provided $117 billion in guarantees for 1,441,745 loans in 2021 – a record level of loans supported through this program. To show how much this program has grown, in 2000, the VA guaranteed less than 200,000 mortgages.

For FY 2022, administrative costs were reported to be the same as in 2021 while the number of FTEs rose to 918. The program’s budget authority provided for a guaranteed loan level of $305 billion, and had a subsidy rate of -0.08 percent, which means that the VA estimates it will collect net offsetting receipts from the loans that defray $216 million in the costs of the program.

For FY 2023, the agency’s budget requests $282 million for administrative costs and to increase FTEs even further to 978. The budget proposed to raise the loan level to $315 billion, and the subsidy rate will rise to 0.08 percent, with a $246 million subsidy cost.

Increasing Liabilities

Separate data from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) indicate that the program has become increasingly risky. The 2023 Federal Credit Supplement provides summary information about federal direct loan and loan guarantee programs. The total outstanding principal of the program has risen dramatically over recent years, as shown in the chart below.

In the first year of the OMB data, the Fund’s outstanding balance stood at $5.8 million. The balance topped $1 billion in 2003 and 2004 before receding slightly. The level topped $2.7 billion in 2009 and $43 billion in 2019. The last two years saw the most dramatic increase, with outstanding principal rising to $209 billion in 2020 and $394 billion in 2021 — nearly 68,000 times larger than the 1992 balance.

CBO notes that the growth in the program "may have resulted from a number of factors, including the stricter underwriting requirements adopted by originators as a result of the housing crisis of the late 2000s and greater use by borrowers of refinancing options through VA.” In 2008, 21 percent of VA-guaranteed mortgages were used to refinance an existing mortgage. That rose to 38 percent in 2019.

VA's lax terms relative to FHA, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac could also be a factor in the growth of the program. CBO reports that "of the borrowers purchasing a home with a guarantee made in 2019, 42 percent were classified as first-time homebuyers and 80 percent made no down payment to purchase their home [emphasis added].”

Fair-Value Accounting and the Loan Program

Congress, through the Fair Credit Reform Act (FCRA) of 1990, requires federal agencies to include default risk when estimating the costs of credit programs. This law stipulates that the discount rate for calculating the present cost of the loan or guarantee is based on projected yields of Treasury securities with the same term to maturity.

This method tends to underestimate the true value of the loans or guarantees because it does not account for the cost of risk involved —market loans being far riskier than Treasury securities. An alternative method called fair-value accounting creates estimates based on the market rate of interest that a private entity would have to pay. Fair-value accounting does a better job of incorporating the risk of defaults.

Because of the growth in VA loan guarantees, CBO took a special look at it, in The Role of the Department of Veterans Affairs in the Single-Family Mortgage Market. VA’s loan program has increased in dollar volume and also as a share of total federal loan guarantees, accounting for 12 percent of all single-family mortgages in 2020.

CBO’s report analyzed the loans VA planned to make in FY 2022. Under FCRA, guarantees of $268 billion in new mortgages that VA is projected to issue would increase the budget deficit by about $2.8 billion. CBO’s estimate is higher than the administration’s because it foresees more defaults over the lifetime of the loan. Under fair-value accounting, however, the liability is estimated at $9.7 billion – over three times larger than the prescribed methodology. CBO argues that fair-value estimates present a more comprehensive picture of the long-term costs of a program.

CBO found similar discrepancies in the cost of the VA loan program assessed through FCRA versus fair-value accounting in a more recent report. In June 2022, CBO estimated the cost of guarantees it expects the VA to issue in FY 2023. In CBO’s evaluation, the VA program would support $265 billion in loan guarantees in FY 2023. Under FCRA, this would have a 1 percent subsidy cost totaling $2.6 billion over the lifetime of the guarantees. Under fair-value, the subsidy estimate is 3.4 percent, representing a $9.1 billion lifetime cost.

The Budget Gimmick

The exponential growth of this program, compounded with the inadequate method used to account for the risk, makes it extremely concerning that lawmakers are regularly using the loan fees that are supposed to defray the cost of one specific program for all sorts of other veterans-related spending.

The most recent example was included in H.R. 6376, the Student Veteran Work Study Modernization Act, passed by the House in May 2022. CBO’s score notes that it would create a pilot program to pay work-study allowances to eligible students who are enrolled at least half-time and are hired by a VA facility, a states’ veterans agency, or a Congressional office. Under current law, recipients are eligible for work-study allowances for those enrolled at least three-quarters of full time. CBO estimates that the expanded program would increase outlays by $3 to $4 million per year through 2027.

But the bill also includes a dubious offset to the new spending. Under current law, the rates for the VA loan fees expire on January 14, 2031. After that date the rated average of the loan rates will drop from 2.5 percent to 1.2 percent. The bill extends the current-law rates through January 23, 2031. This nine-day extension will net $20 million in offsetting receipts, more than offsetting the new spending through the initial years of the budget window.

As egregious as this example is, it is just the most recent example of this budget gimmick. The table below shows the laws enacted since 2011 that either increase the VA mortgage loan fees or extend the period of time for higher rates. The common element of these laws is that they all increase spending on veterans benefits, generally in the earlier years of the budget window, and either completely or partially offset that spending with changes to loan fees.

The data also shows that over time, the duration between the enactment of the change and the extended fee rates grew. The Restoring GI Bill Fairness Act of 2011, passed in August of that year. The bill modified the amount of education benefits payable to certain veterans and dependents for three years, beginning on August 1, 2011. It offset this spending by extending certain loan fee dates to October 1, 2011 and others through October 1, 2012.

A few months later, the Veterans Health Care Facilities Capital Improvement Act of 2011 extended certain rates that were set to expire on October 1, 2011 until November 18, 2011. This provided a $31 million offset to a bill to increase spending by over $1.1 billion on construction of health care facilities.

Roughly six weeks later, the VOW to Hire Heroes Act, passed as part of a larger package in H.R. 674, extended certain rates through October 1, 2016 to offset an expansion of GI benefits and Vocational and Rehabilitation and Employment Benefits.

The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 was the first law that extended fees out to the tenth budget year in order to partially offset a law providing appropriations for veterans to seek health care from non-VA entities. The subsequently enacted laws generally continued that practice of extending the fees at the end of the budget window.

Recommendations

Lawmakers should consider enacting a point of order against the use of offsets that only appear in the ninth or tenth budget year of the underlying bill, especially in cases where the spending is front-loaded and the offset is already intended to pay for something else. The dramatic growth in the amount of loans backed by the VA should be a further reason why lawmakers should not tap these veterans’ mortgage loan fees for anything other than a reserve to cover any future veterans’ mortgage loan defaults.

Lawmakers should also implement fair-value accounting to accurately assess the risks entailed with this loan guarantee program. Fair-value is the method used by private-sector lenders and should be used for all federal credit programs. Representative Ralph Norman’s (R-SC) Fair Value Accounting and Budget Act, H.R. 3785, would make this the standard.

Last year, NTUF wrote about a similar budget gimmick. Lawmakers frequently include an extension of customs user fees for an additional period of time 9 or 10 years out in all sorts of spending packages (at least the VA loan fee has been restricted to offsetting the cost of other veterans programs). The recommendation NTUF made for the customs user fees budget gimmick also applies to the misuse of the VA loan fees:

Congress should consider changing budget rules so that customs user fees are scored on a so-called “current policy” baseline instead of a “current law” baseline. A current policy baseline provides more realistic budget projections that are based on the policies that Congress tends to enact, rather than based on a strict reading of current law. Without reforms, some Members of Congress will continue to use this budget gimmick in perpetuity in order to facilitate big spending packages. Instead of allowing the practice to continue, budget-conscious Members should advance changes that ensure these fees are included permanently in the baseline to prevent the use of this ploy.

Conclusion

The use of this budget gimmick is one reason why deficits keep growing, even though Congress passes laws that are, on paper, paid for. Moreover, it is extremely concerning that lawmakers continue to use the loan fees as offsets for other veteran benefits programs while the size of the guarantee has skyrocketed from $6 million in 1992, to $87 million in 2000, to $3.4 billion in 2010, and approaching $400 billion in 2021.