(pdf)

Introduction

NTUF’s Taxpayers’ Budget Office has pointed out several shortcomings the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) current-law budgetary baseline that understate the level of likely spending and overstate tax revenues. These misleading projections are occasionally a result of faulty assumptions on CBO’s part, but more frequently they exist because Congress directs the agency to score in a manner that masks the true scale of our fiscal imbalance.

We recently became aware of another oddity in the official baseline. CBO’s budget projection includes the collection of $4 billion in fees related to management of nuclear waste despite the fact that they have not been collected since 2014. These phantom receipts are yet another example of the misleading nature of current-law estimation as opposed to current-policy projection.

CBO’s Score

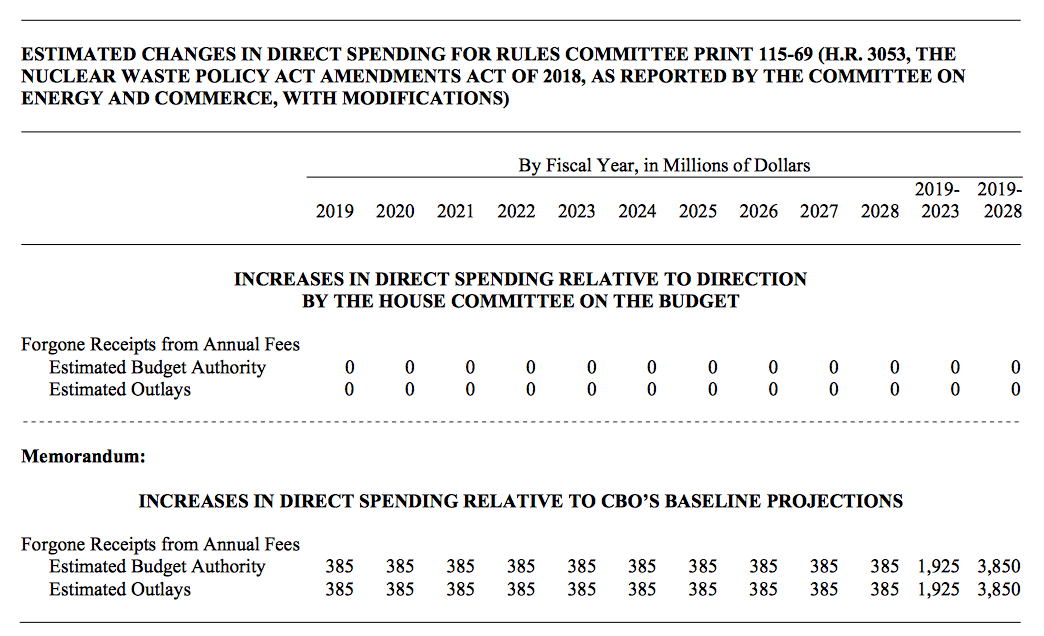

The issue came to light in a CBO cost estimate for H.R. 3053, the Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 2018. CBO’s score features a table with two sets of numbers: one showing zero change in spending over the next decade “relative to direction by the House Committee on the Budget” and another set of numbers showing an annual $385 million increase in direct spending “relative to CBO’s baseline projections.” Different than tax revenues, these types of fees are recorded in the budget as offsetting receipts to spending, so the table shows the foregone fees as leading to higher levels of spending in CBO’s baseline.

At first glance, it appears as though CBO is indicating that the Budget Committee is trying to fudge the numbers in order to mask the bill’s impact on the deficit. The score, however, leaves out the fact that the fees have not been collected for several years following a court order in late 2013.

Background on the Nuclear Waste Policy

The fees, established in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982, were assessed on nuclear power generators at the rate of a tenth of a cent per kilowatt-hour. They raised approximately $750 million per year for the intended purpose of permanent disposal of nuclear waste in a deep geologic repository. A 1987 amendment to the law restricted site studies to Nevada’s Yucca Mountain. The Department of Energy submitted a license application for a repository at the site in 2008. The state of Nevada adamantly opposed the plan citing a range of concerns, and the Obama Administration subsequently halted the process. Appropriations for the program stopped after 2010 while an attempt was made to work out a consent-based approach to agreeing on a site.

Meanwhile, despite the lack of a plan, the fees were still being assessed. This prompted a lawsuit from the utilities challenging the legality of the fees. The Department of Energy (DoE) has authority to adjust the fees as necessary in order to cover the program’s costs. The utilities argued that in the absence of a plan there is no reasonable basis upon which to determine fee rates. In November of 2013, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit agreed, ordering DoE to set the fee rate to zero due to the uncertainty over the repository.

Gone … But Not Forgotten in the Baseline

Six years since the court ruling, there has been essentially no progress on finalizing a plan to manage and deposit the nation’s nuclear waste. Last year’s bill, H.R. 3053, would have changed the law so that the fees could not be assessed until the Nuclear Regulatory Commission issues a decision on the license to proceed with the Yucca repository, and it would have changed the program from mandatory spending to discretionary, which generally entails greater programmatic oversight over annual funding levels. In order to achieve a more realistic budgetary score, the Budget Committee instructed the CBO to assume that no fees would actually be collected over the next decade – reflecting current policy (or lack thereof).

Despite the policy stalemate, CBO still includes the fees in its baseline projection of federal revenues and outlays. This is because CBO is instructed to produce its baseline based on current law. Even though the fees have been unenforceable for a number of years, they are still law. In 2015 CBO testified that given the “possibility—that the Administration could pursue actions, under current law, to reinstate annual fees—CBO’s baseline follows the agency’s usual practices for projecting spending and receipts related to activities involving uncertain administrative actions.”

Reflecting a 50/50 chance that the fees will be restored, “CBO estimates the total amounts that would be collected if fees were fully reinstated and includes 50 percent of those amounts in its baseline.”

CBO also noted that the Obama administration used the same methodology regarding the fees, but that is not the clearest way of constructing the baseline. In this particular case, the inclusion of the uncertain fees into the baseline projection makes the deficit look $3.85 billion smaller over the decade than it would be given a more realistic baseline based on current policy.

Conclusion

CBO’s confusing cost estimate for the Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act of 2018 illustrates the shortcomings of the current law baseline and it also raises questions of clarity. There are many instances in which lawmakers cleverly craft legislation in order to game CBO’s scoring process. NTUF recently highlighted an example of this in a bill designed explicitly to boost spending from the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund yet which was given a score of zero. Other reports and analyses from CBO regarding the nuclear waste fees provide details on the stalled process, noting that fees have not been collected in several years. Without this context, CBO’s score of H.R. 3053 made it seem as though lawmakers were similarly trying to rig the process, but this was not the case. They were ensuring that CBO’s score would take existing policy into account and provide a more realistic budgetary projection. Congress should instruct CBO to use current-policy projections more broadly.