(pdf)

Introduction

Earlier this year, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its economic and budget baseline which projected that $13 trillion would be added to the debt over the next decade.[1] At the time, NTUF noted that the budget picture would be expected to look worse than reported through no fault of CBO’s analytical acumen.[2] The problem is that Congress requires CBO to produce the baseline using assumptions that spending and revenues will continue largely as they are set under current law. This methodology tends to mask outlays that will continue even though they may be set to expire, and it overcounts revenues by not taking into account tax breaks that are typically extended beyond their expiration date. And in a normal year, there is always the caveat that an unexpected emergency or natural disaster could completely change the budget picture.

We are no longer operating under normal conditions because of the coronavirus pandemic and the economic shutdown. So far three rounds of legislative packages have been enacted to address the health care crisis and to blunt the economic damage, and there is already talk about what might be included in a fourth bill. Congress and the President have adopted a war footing to combat the health and economic crises. After these challenges are faced down, Congress will need to focus with equal zeal and in a similar bipartisan spirit to the task of setting the budget on a sustainable path.

CBO’s Revised Baseline

CBO frequently reminds its readers that the baseline is not meant to be a “forecast of future budgetary outcomes.” Its primary purpose is to serve as the yardstick against which policy proposals are measured as CBO’s analysts produce cost estimates. However, the projections do also serve as a recurring reminder to lawmakers that the long-term budget is badly out of balance given the trajectory of spending and revenues under current law.

CBO generally produces an updated baseline projection in March that integrates the latest program-level inflow and outflow data reported in the President’s budget. Generally released in February, the President’s budget includes the administration’s proposals for the next fiscal year and also detailed information on spending levels for the current fiscal year. In addition to incorporating this data, CBO’s March baseline also takes into account legislative and technical changes. This year, the revised baseline was published on March 19 but was only based on additional legislation enacted through March 6.

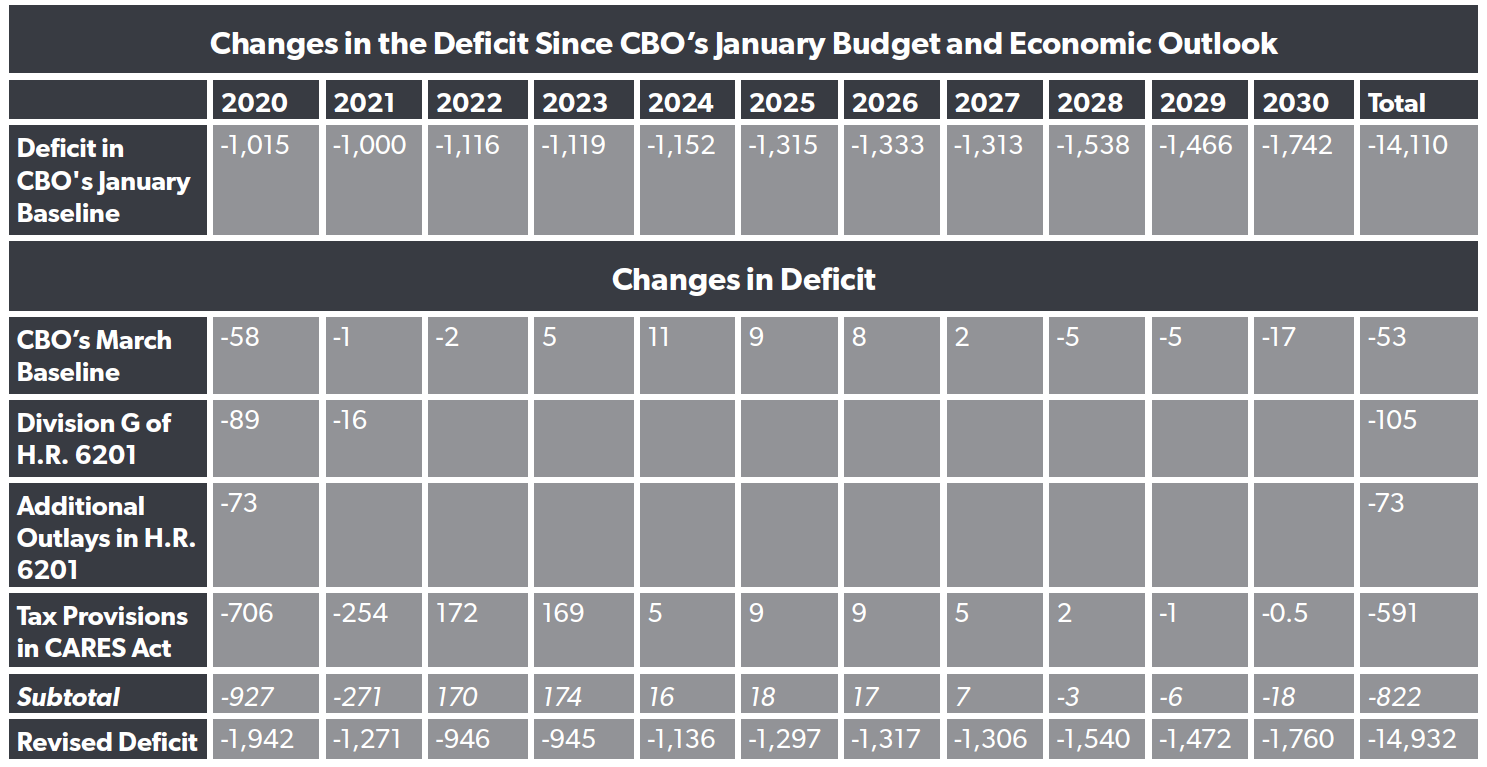

CBO determined that from the January baseline through March 6, the deficit for this year grew from $1.015 trillion to $1.073 trillion - a $58 billion increase. A portion of the change was attributable to two laws enacted since January:

- H.R. 6074, the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, added $8 billion in discretionary budget authority for this year in response to the growing public health crisis. Under the budgetary rules, these funds are assumed to continue in the baseline, growing at the rate of inflation over the budget window.[3]

- H.R. 5430, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Implementation Act impacted revenues through a provision that CBO estimated would increase tariff revenue on motor vehicles and parts by $10 million this year and a total of $3.4 billion over the next decade.[4]

In net, the changes in revenues and outlays due to enacted legislation are expected to increase debt service costs by $8 billion through 2030, relative to CBO’s $5.9 trillion January estimate.

A much larger ($57 billion) deficit change for fiscal year (FY) 2020 resulted from technical changes regarding cost information from previous estimates. For the subsidy costs of loan programs, CBO uses amounts reported by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). OMB revised the subsidy costs for student loans, adding $83 billion to this year’s deficit. On the positive side, CBO’s technical changes had estimated lower outlays for Medicare due to a slower rate of growth in spending and lower outlays for Social Security, and Disability Insurance due to a lower estimate of beneficiaries.

Changes Since the Revised Baseline Deepen the Federal Debt

Unfortunately, events impacting the budget outlook have been moving at light speed since CBO produced the revised baseline in early March. On March 18, Congress enacted the second coronavirus response package, H.R. 6201, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act.[5] The bill provided $1 billion for an Expanded Unemployment Insurance benefit, increased federal funding for Medicaid, and an emergency paid sick leave and emergency family medical leave expansion.

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) produced an analysis of the budget impact of the tax credits for paid sick and emergency leave.[6] JCT estimates it would add $89 billion to deficits this year and $16 billion in FY 2021. A complete official cost analysis has not been released yet, but the American Action Forum, led by former CBO Director Douglas Holtz-Eakin, estimated that the other provisions in the bill would cost at least $73 billion.[7]

On Friday March 27, Congress enacted H.R. 748, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act after a unanimous vote in the Senate and a voice vote in the House of the members who traveled to DC to ensure the presence of a quorum.[8] The massive package includes loans to businesses (which can be eligible for forgiveness if employees are retained), supplemental funding for several government entities (including a $25 million plus-up for the Kennedy Center on top of their FY 2020 $25.6 million appropriation), recovery rebate payments to individuals, and payroll tax relief for employers and workers.

CBO has not yet produced a cost estimate of the legislation but widely-reported preliminary White House estimates put the price tag at $2.2 trillion. A subsequent JCT analysis of the CARES Act’s tax provisions estimates a hike in the FY 2020 deficit of $706 billion, but as temporary waivers expire, the net ten-year revenue loss is projected at $591 billion.[9] This figure could grow if Congress decides to increase the levels of loan forgiveness or further extends the waivers.

The largest revenue provision is $292 billion for the recovery rebates, which will be paid out to individuals or joint filers. The second largest immediate impact results from the payroll provision which would provide a delay in employer obligations. JCT projects that this will reduce revenues by $211 billion this year but after the delayed payments, the net impact would be $12 billion through 2023, because this is largely a timing shift, not a change to the underlying tax policy.

As noted, CBO has not had time to complete a cost estimate for the spending provisions of the CARES Act, but it is safe to assume that they will add at least $1 trillion to the ten-year deficit. Looking ahead, lawmakers will probably work to prevent a massive tax hike from hitting taxpayers as the tax reductions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 are set to expire under current law. Business provisions start to expire in 2022 and the individual provisions will expire in 2026 . CBO data shows that extending the individual income tax relief would reduce revenues by $1.15 trillion through 2030.[10]

Economic Factors

Obviously, other factors will greatly impact the budget projection. Because of the loss of jobs and the halt of significant economic activity, revenues will be much less than forecast and outlays will increase for unemployment payments and other safety-net entitlement programs. Before this year’s budget, CBO generally included a chapter in each budget and economic outlook that included a discussion of alternative fiscal outcomes. That was not done this year, but CBO did produce a follow up paper discussing how changes in the economic outlook might alter the budget outlook.[11] CBO analyzed four key economic variables and devised rules of thumb for each:

- Productivity: if productivity grows 0.1 percent less each year than CBO’s projection, deficits would be $306 billion larger over the decade.

- Labor force: if the labor force grows 0.1 percent slower each year than CBO’s projection and unemployment remains unchanged, deficits would be $162 billion larger over the decade.

- Interest rates: if interest rates are 0.1 percent higher each year than CBO’s projection, deficits would be $185 billion larger over the decade.

- Inflation: if all wage and price indexes are 0.1 percent higher each year than CBO’s projection, deficits would be $148 billion larger over the decade.

CBO also produced an interactive workbook to illustrate how changes in the variables will affect the flow of revenues to the treasury.[12] Users can select positive or negative changes for each of these four variables for each year over the decade, and the workbook will compute the changes in the levels of deficit and debt.

However, the CBO notes that the workbook was designed specifically for the rules of thumb and that calculations are only plausible within certain ranges for each variable. If productivity is down by 0.5 percent this year (the lowest usable rate for the spreadsheet), this would increase the ten-year deficit by $201 billion. If labor growth is 0.75 percent lower (the lowest usable rate) in FY 2020, $135 billion would be added to the ten-year deficit.

Due to the unprecedented economic shutdown to halt the spread of the coronavirus, CBO’s rules of thumbs can no longer be applied. Economic downturns also lead to an increase in outlays for an extended period of time as more Americans access social safety net programs. It is also unclear how long the situation will last or how quick a recovery might be, but this year’s deficit could be expected to be more than triple -- or in a worst case scenario quadruple -- the projection from earlier in the year.

Principles for Fiscal Prudence

Provisions enacted in emergency legislation should be timely, targeted, and temporary. If Congress does put together a fourth phase bill, lawmakers should ensure that it adheres to these principles, providing aid as swiftly as possible to those who need it, and there should be time limits on the programs. Politicians should resist the urge to take advantage of the situation by larding up the legislation with long-sought pet projects or by creating costly new permanent programs, such as the push by some Democrats for a new federal paid leave entitlement. All practical attempts should also be made to ensure transparency of the spending that has been enacted.

Conclusion

CBO had already painted a grim fiscal outlook based on current law in January. Even before the impacts of the COVID-19 health crisis were felt, budget observers knew the outlook was in fact even worse than CBO’s projection given Congress’s habit of adding to the deficit each year. With the onset of a global health pandemic and the resulting economic disruptions, the simple truth is that the budget math is as bad as it has ever been. We are now living through an historic health crisis that has threatened people’s lives and is also putting a heavy strain on the budget through increased spending and a drop-off in revenues. Even if the health emergency passes under optimistic timelines, and the economy roars back, the budgetary pressures will linger.

After we weather this storm by stopping the spread of the virus and turning back on the engines of the economy, lawmakers must turn to the task of averting a budgetary crisis. The path of federal debt is unsustainable. Continual deficit spending at these massive levels severely restricts the government’s ability to respond to the next crisis. While Congress must focus today on addressing the impacts of COVID-19 on our health and our economy, it must focus tomorrow on safeguarding our economic liberty from the threat of overwhelming debt.

[1] Congressional Budget Office, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2020 to 2030,” January 28, 2020. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56020

[2] Brady, Demian, “The Budget Outlook Is Even Worse than Advertised,” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, January 28, 2020. https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/the-budget-outlook-is-even-worse-than-advertised.

[3] H.R.6074 - Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020,” March 6, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074.

[4] H.R.5430 - United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement Implementation Act, December 13, 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/5430/text.

[5] H.R.6201 - Families First Coronavirus Response Act, March 11, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6201.

[6] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects Of The Revenue Provisions Contained In Division G Of H.R. 6201, The ‘Families First Coronavirus Response Act,” March 16, 2020, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5250.

[7] Soto, Isabel and Tara O’Neill Hayes, “Estimating the Cost of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act,” American Action Forum, March 17, 2020, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/estimating-the-cost-of-the-families-first-coronavirus-response-act/.

[8] Joe Courtney, “H.R.748 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): CARES Act” (2020), https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748.

[9] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects Of The Revenue Provisions Contained In An Amendment In The Nature Of A Substitute To H.R. 748, The ‘Coronavirus Aid, Relief, And Economic Security ('CARES’) Act,’ As Passed By The Senate On March 25, 2020, And Scheduled For Consideration By The House Of Representatives On March 27, 2020, ” March 26, 2020, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5252.

[10] Congressional Budget Office, “Date Underlying Figures,” January 28, 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-01/56020-data-underlying-figures.xlsx.

[11] Congressional Budget Office, “How Changes in Economic Conditions Might Affect the Federal Budget: 2020 to 2030,” February 6, 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-02/56096-CBO-rules-of-thumb.pdf

[12] Congressional Budget Office, “Workbook for How Changes in Economic Conditions Might Affect the Federal Budget,” February 6, 2020, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56097.