(pdf)

Remote work is here to stay. The Census Bureau estimates that the number of Americans working remotely tripled between 2019 and 2021, from 9 million to 27.6 million. While some Americans have returned to in-person work, many maintain remote or hybrid work arrangements.

But while these more flexible forms of work offer benefits to Americans who prefer to avoid commutes or spend more time at home, many of those who switched have been surprised to find that they owe income taxes to multiple states, while businesses have faced withholding and business income tax obligations in new states.

Making things more complicated, remote work subjects taxpayers to changes that can be difficult to predict, as they depend on each state’s laws. Policies that can muddy the waters and even create the potential for double taxation include:

Filing thresholds - Thresholds that taxpayers must exceed before being required to file an income tax return in a state.

Reciprocity agreements - Agreements between states that allow taxpayers who commute across state lines to pay income taxes only to their state of residence.

“Convenience of the employer” rules - Requirements that taxpayers who switch from commuting into a state to working remotely in another state must keep paying income taxes to the state they used to commute into so long as they could possibly have continued commuting.

Individual income tax code - Different states’ tax codes affect taxpayers caught up in them differently, and having nexus in higher-tax states is more burdensome for taxpayers than having nexus in others.

Withholding thresholds - Thresholds that employees must exceed in a state before employers are required to withhold income taxes on the employees’ behalf.

This inaugural edition of the Remote Obligations and Mobility (ROAM) Index ranks states on the burdens they place upon remote and mobile workers and their employers. Remote workers are defined in this analysis as employees who work either fully remote or on a hybrid schedule of commuting to work and working from home. Mobile workers are employees who travel around the country as part of their job. This report uses laws as they stood as of the end of 2022.

Which states are the best? The nine states without an individual income tax and the District of Columbia are set aside from the other 41 states in the ROAM Index. Those nine states with no individual income tax do not impose any income tax burdens on taxpayers working remotely in-state, for obvious reasons. Though there are differences between these states in terms of taxation of capital gains or dividend income, all nine states with no individual income tax are ranked in a tie for first place in the ROAM Index.

The District of Columbia would receive the highest score of any state with an individual income tax, but this is because it is prohibited by the federal Home Rule Act from taxing nonresidents. Consequently, D.C. lacks the ability to impose harmful tax obligations on remote workers even if it wanted to. D.C. is therefore not ranked on the ROAM Index, though it would slot in between the nine states with no income tax and the top-ranked state with one, West Virginia, if it were.

Factors Included In the Rankings

The ROAM Index considers five factors to develop a comprehensive ranking of each state.

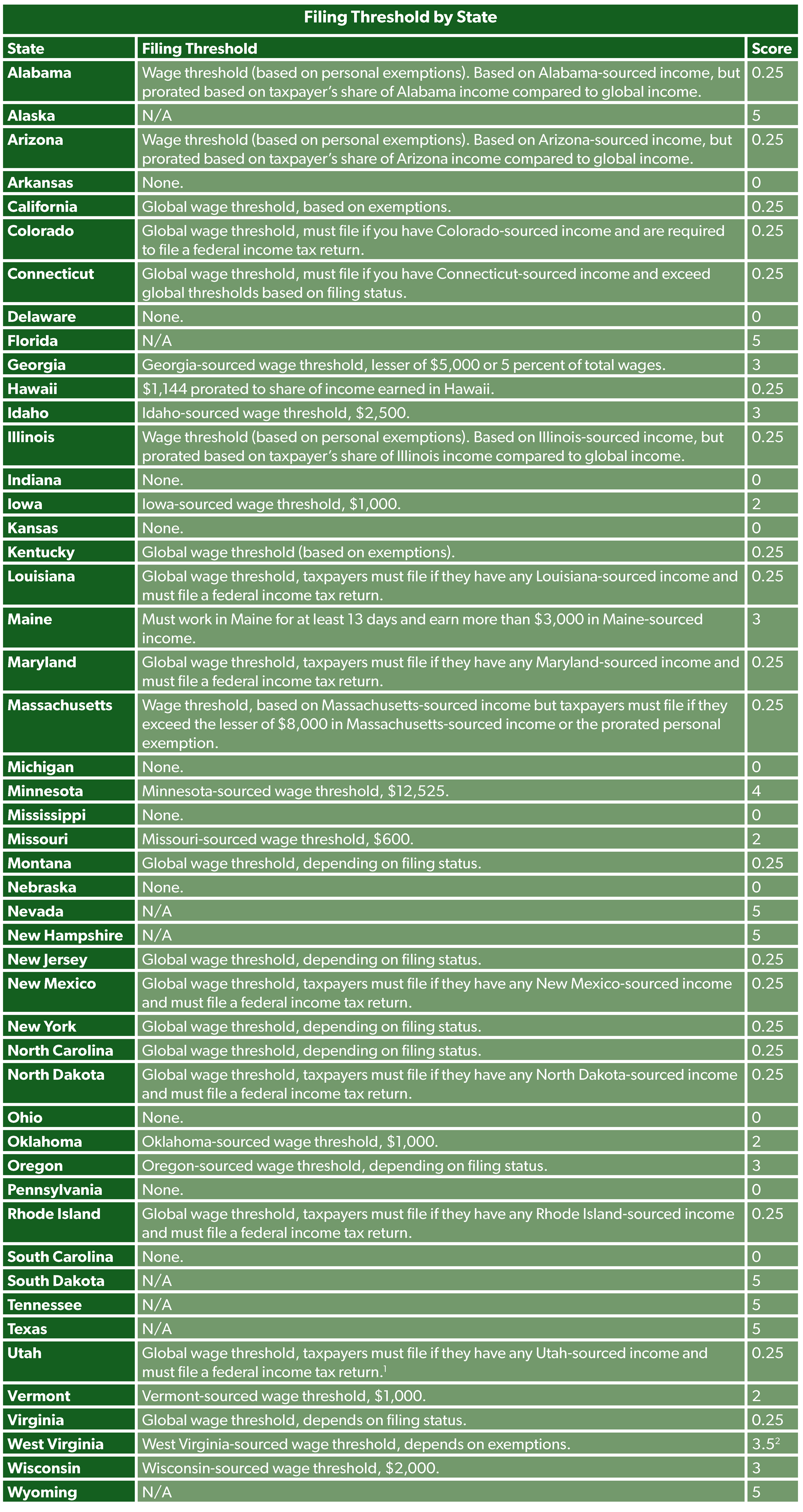

Filing Thresholds

Filing thresholds represent how long a taxpayer must work in a state before the taxpayer must file an income tax return in that state. Different states have different rules about the requirements taxpayers must fulfill before having to file an individual income tax return in each state. For all but eleven states, taxpayers must file if they earn any income in the state at all, or if they earn any income in that state and must file a federal income tax return. As the vast majority of wage earners have to file a federal individual income tax return, the latter threshold provides barely any protection at all.

Only one state has a defined day threshold for taxpayers — Maine. Nonresident workers in the Pine Tree State must only file an individual income tax return after they have worked 12 days in-state and earned $3,000 in wages. In ten other states — Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Oklahoma, Oregon, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wisconsin — a taxpayer must file an individual income tax return after surpassing a wage threshold in-state, sometimes depending on exemptions.

Day thresholds provide more certainty to taxpayers regardless of income, but wage thresholds can nevertheless provide some protection against burdensome filing obligations. To compare wage thresholds to day thresholds, we looked at the number of days a taxpayer earning the median income in each state would have to work to surpass the threshold. We assumed that the single filer has zero dependents and the married filer has one, in line with national averages.

States were then scored on the following basis:

0 points: No threshold at all. This requires taxpayers to file in a state from the first dollar they earn in that state.

0.25 points: Global wage threshold, or a threshold that looks at total income a taxpayer earns, not just income earned in-state. This does very little to help taxpayers, as the vast majority of wage earners will still have to file in a state from the first dollar they earn in that state. As such, there is a significant gap between the score this type of threshold and even a low state-sourced wage threshold earns.

2 points: Low state-sourced wage threshold, requiring taxpayers to file in-state from the 2nd to the 6th day, or equivalent based on the state median income, worked in that state. Low thresholds at least protect taxpayers from having to file an individual income tax return in a state on the basis of very minimal time worked in-state.

3 points: Medium state-sourced wage threshold, requiring taxpayers to file in-state from the 7th to the 20th day, or equivalent based on the state median income, worked in that state. Medium thresholds protect taxpayers from having to file an individual income tax return in a state on the basis of a short time worked in-state.

4 points: High state-sourced wage threshold, requiring taxpayers to file in-state from the 21st day to the 30th day, or equivalent based on the state median income, worked in that state. High thresholds provide substantial protection to taxpayers, but fall just short of the gold standard.

5 points: Defined >30-day threshold, requiring taxpayers to file in-state only after they work more than 30 days in-state, not counting equivalent days worked on the basis of a wage threshold. This is the gold standard that all states should aspire to. Unfortunately, no states earned 5 points from this category this year.

The best-performing state in this category is Minnesota, which earns a 4. While Minnesota has a threshold that would exempt a taxpayer earning a median income in-state for more than 30 days, it does not earn the full 5 points due to having a high wage threshold rather than a statutory 30-day threshold. This factor is also double-weighted, meaning a 4/5 earns 8/10 points.

Some competing model bills attempt to address this. One model from tax administrators at the Multistate Tax Commission (MTC) has been adopted by two states (North Dakota and Utah) and includes a threshold of 21 days, but undercuts it by only applying it to residents of states that do not have an individual income tax or have also adopted the same model law, and would not apply to many different subsets of employees. A better model from the Council on State Taxation (COST) has a threshold of greater than 30 days but also would only apply to residents of states having adopted the same model bill or lacking an individual income tax.

To improve in this category, states should enact a filing threshold that requires taxpayers to file an individual income tax return only after they have worked in the state for more than 30 days, and is not contingent upon widespread adoption of similar rules.

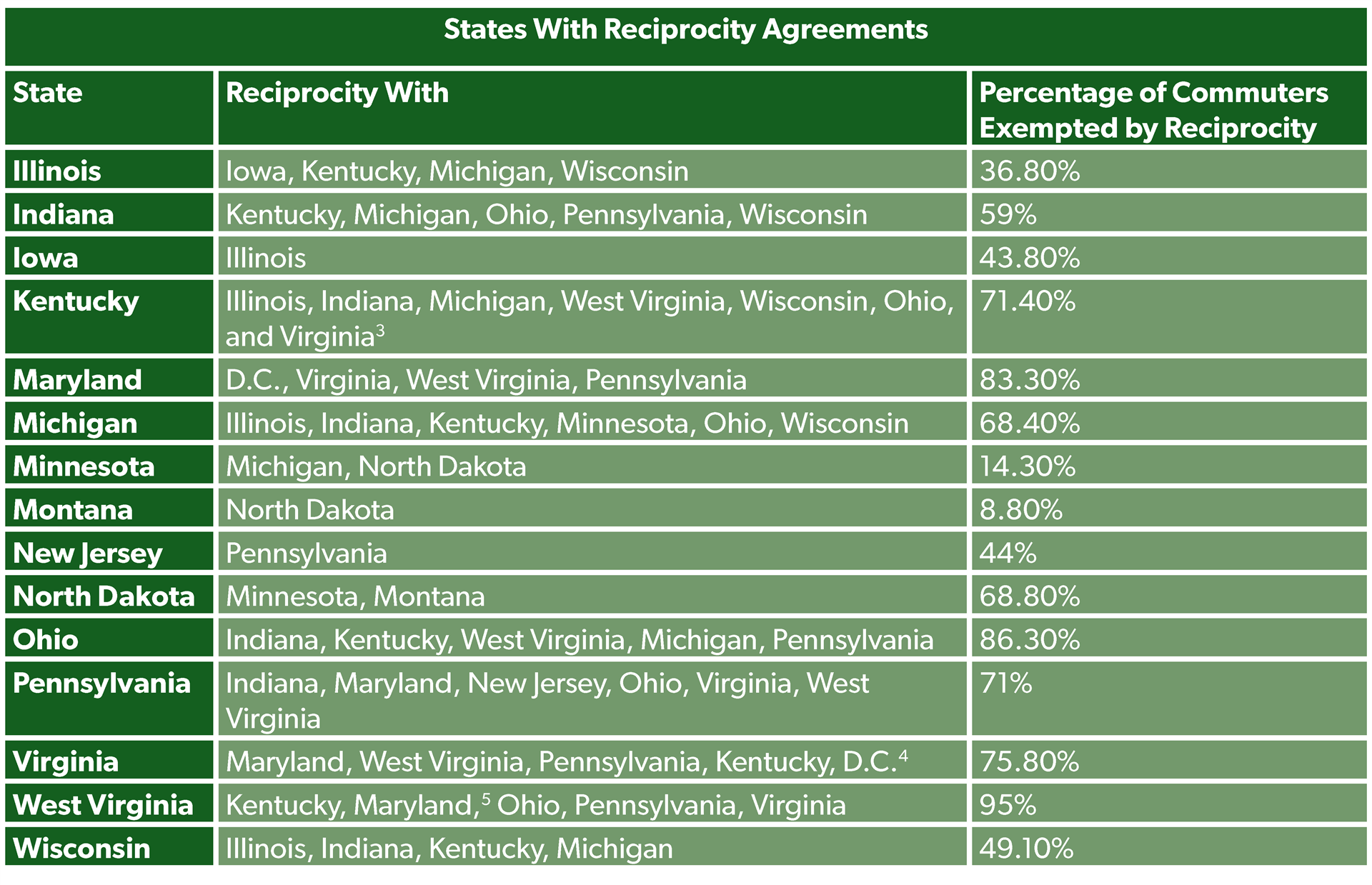

Reciprocity Agreements

Reciprocity agreements are agreements between states to treat taxpayers who live in one state but work in another as working in their state of residence for tax purposes. In other words, a taxpayer residing in Virginia who commutes to a job in Maryland pays income taxes only to Virginia where they live, because the two states have a reciprocity agreement.

To model the impact of states’ reciprocity agreements, we looked at the last release of American Consumer Survey commuting data to see how many workers are exempted by each reciprocity agreement. Though this is for the years 2011-2015, it nonetheless provides a picture of how many workers are exempted by each reciprocity agreement. States are then ranked on a ten-point scale on what percentage of commuters into the state are exempted from filing taxes to that state due to reciprocity agreements. A state exempting 100 percent of its workers would receive a 10/10, while a state exempting 52 percent of its workers would receive a 5.2/10, and so on.

With the exception of the District of Columbia, no state exempts 100 percent of commuters from income tax obligations via reciprocity agreements. The closest state is West Virginia, which exempts approximately 95 percent of commuters via its reciprocity agreements with Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Other states exempting more than three-quarters of incoming commuters via reciprocity agreements are Maryland, Ohio, and Virginia.

Of course, not all reciprocity agreements are created equal. Arizona, for example, has what are often referred to as “reciprocity agreements” with California, Indiana, Oregon, and Virginia, but these are not truly reciprocity agreements. Instead, Arizona residents pay taxes to Arizona, but must also file in California. California provides a credit against taxes paid to Arizona, but then Arizona residents must still pay the residual amount to California due to California’s higher rates. Arizona residents pay the same amount as if there was no reciprocity agreement at all, and still have to file in two separate states; the only difference is in how much tax is paid to each state. Consequently, NTUF does not count Arizona’s agreements as true “reciprocity agreements.”

Reciprocity agreements can have differing impacts. For example, New Jersey’s single reciprocity agreement with Pennsylvania exempts a greater share of commuters into the state than Illinois’s four reciprocity agreements with Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, and Wisconsin combined.

To improve in this category, states should enter into reciprocity agreements with neighboring states, particularly neighbors that have the highest commuter traffic into their state. State legislators can also provide the heads of their Departments of Revenue with statutory authority to enter into bilateral agreements, or they can extend unilateral offers of reciprocity to any state that provides the same treatment in return, as Indiana, Minnesota, and Wisconsin do.

So-Called “Convenience of the Employer” Rules

“Convenience of the employer” rules are requirements that taxpayers who live and work in another state must nevertheless pay income taxes to their employer’s state, even if they may never physically set foot in it. The term comes from New York, which imposes such a rule on employees of in-state companies unless the taxpayer proves to New York officials that working remotely is a necessity, not merely a “convenience.” Taxpayers rarely win.

For example, a New Jersey resident commutes from New Jersey to an office in New York City. Growing tired of the long commute, the New Jerseyan receives permission from their employer to switch to remote work from their New Jersey home. Because New York has determined that avoiding a commute is merely “convenience,” New York requires the taxpayer to continue paying New York income taxes.

Convenience of the employer rules are fundamentally illogical and cause significant confusion. These rules are also particularly harmful because they can result in double-taxation. Generally, when a taxpayer is required to file taxes in two states, they can receive a credit against taxes paid to one of the states, thereby avoiding being taxed by two states on the same income. However, when a high-tax state like New York claims the power to tax the income of a taxpayer who lives and works in another state, there is the risk of the taxpayer being caught in a tug-of-war between the two states, risking double-taxation.

Four states impose convenience of the employer rules: Delaware, Nebraska, New York, and Pennsylvania. Each of these four states earns a flat -5 point penalty to their overall score. Connecticut imposes a retaliatory version against states that have their own convenience of the employer rule only — while retaliation against these states is understandable, taxpayers are ultimately the ones hurt. Consequently, Connecticut earns a reduced penalty of -2.5 points.

Some states do not receive a penalty but may in future editions of this ranking. Massachusetts imposed a convenience of the employer rule for the duration of the pandemic, then rescinded it when New Hampshire brought a challenge against the rule to the U.S. Supreme Court. Nevertheless, Massachusetts could reinstitute the rule at any moment. Meanwhile, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy has pushed to institute a retaliatory convenience of the employer rule along the lines of Connecticut’s. Arkansas also had a convenience of the employer rule but repealed it in 2021.

Should these states institute their own convenience of the employer rules, their score and ranking on the ROAM Index would drop significantly. New Jersey’s retaliatory convenience rule would drop it from a middling 36th place to 42nd, while a full Massachusetts convenience rule would drop the state from 39th place to 48th, or third-to-last.

To improve in this category, states with convenience of the employer rules, even retaliatory versions, should repeal these rules. States without convenience of the employer rules can also consider passing legislation prohibiting their Departments of Revenue from instituting them.

“Convenience of the employer” rules are unique in that they affect remote workers through actively harmful policies, not just through inaction. Consequently, they are the only metric in this ranking that earns a state negative points.

Individual Income Tax Code

While it is not the most important factor in considering a state’s friendliness to remote and mobile workers, it is worth considering how burdensome it is to be caught in each state’s tax net. As such, the ROAM Index does consider a state’s individual income tax code as part of its score.

To do this, we borrow from the Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index (SBTCI), specifically the individual income tax component. Under the SBTCI’s individual income tax component, each state receives a score out of ten points that considers rates, structure, deductions, inflation indexing, and tax treatment of married couples, among other factors.

The SBTCI’s individual income tax component is on a 10-point scale, but is only half-weighted. States receive their SBTCI individual income tax component score out of five points.

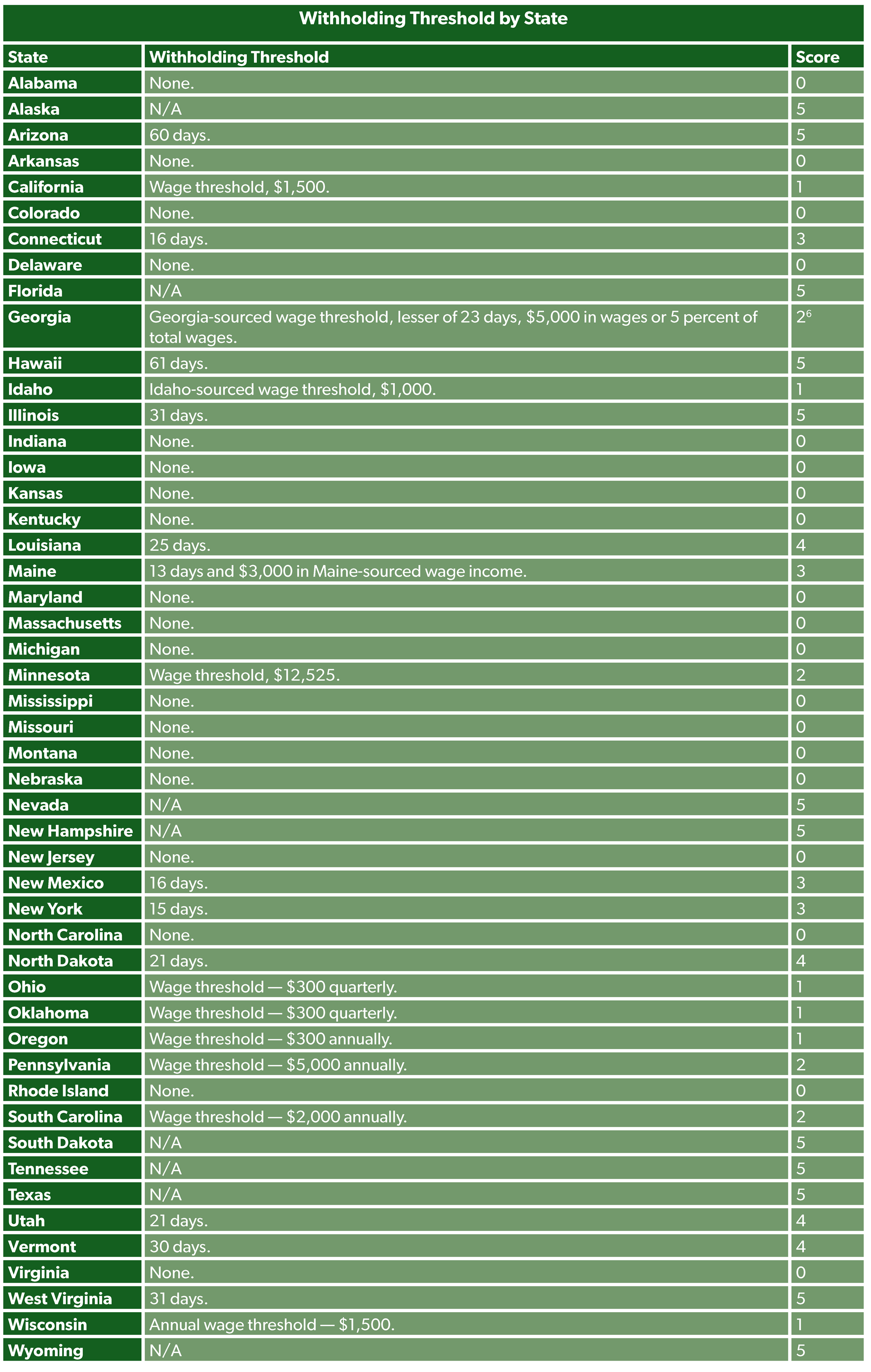

Withholding Thresholds

Only one factor in the ROAM Index directly measures business burdens, but one that is very impactful for small and medium-sized businesses with employees who travel. Withholding thresholds represent threshold that employees must exceed before a business is required to withhold income taxes on the employee’s behalf. Similar to filing thresholds for individuals, businesses can benefit from thresholds before they must withhold income taxes on behalf of employees earning income in a given state.

On this front, states have made more of an effort to provide relief than on filing thresholds. 23 states have at least some threshold that employees must exceed before their employer is required to withhold individual income taxes on their behalf. States with wage thresholds also never make those thresholds global — in other words, withholding thresholds are always based on income earned in-state.

However, in this case translating a dollar value wage threshold into equivalent days worked by an employee making the median in-state income does not make sense, as a business with multiple employees in-state earning different wages has a harder time translating income earned in a state to threshold levels. A business that has multiple employees working in a state over the course of the year can more easily hit a wage threshold even if those employees do not work in-state for very long.

For this section, states are scored on the following basis:

0 points: No threshold at all. This requires businesses to withhold employees’ income taxes in a state from the first dollar they earn and first day they work in that state.

1 point: Low wage threshold, or a threshold of up to $1,500. This requires businesses to withhold employees’ income taxes if wages paid to employees from work performed in-state exceed the threshold. This provides some protection for a business with employees working in-state for a short time, but is not difficult to exceed.

2 points: High wage threshold/low day threshold, or a threshold of over $1,500 in wages or 2-6 days worked in-state. This requires businesses to withhold employees’ income taxes if wages paid to employees from work performed in-state or employees’ days worked in state exceed the threshold. While higher wage thresholds such as Minnesota’s $12,525 can provide substantial protection, they nevertheless offer less certainty than a defined-day threshold.

3 points: Medium day threshold, or a threshold of 7-20 days worked in-state. Medium thresholds provide definite protection for businesses from having to withhold employees’ income taxes in a state on the basis of a short time worked in-state.

4 points: High day threshold, or a threshold of 21-30 days worked in-state. High thresholds provide definite protection for businesses from having to withhold employees’ income taxes in a state on the basis of a moderate amount of time worked in-state, but fall just short of the gold standard.

5 points: Defined day threshold, or a threshold of over 30 days worked in-state. A 31-day threshold provides the gold standard of protection for businesses, ensuring that they will only face withholding obligations for employees who work a substantial amount of time in a given state.

A few states receive a perfect score in this section. Arizona, Hawaii, Illinois, and West Virginia all have thresholds exceeding 30 days. Vermont very nearly reaches this standard, but falls just short with a 30-day, rather than a more than 30 day threshold. The distinction is slight, but a threshold greater than 30 days would exempt an employer from withholding requirements for an employee who works six weeks in-state, whereas Vermont’s would not. This factor is also double-weighted, meaning a 4/5 earns 8/10 points.

Similar to withholding thresholds, the MTC and COST model bills address withholding thresholds as well. The MTC model bill includes a 21-day threshold, while COST recommends the gold-standard of greater than 30 days.

To improve in this category, states should enact a withholding threshold that requires businesses to withhold employees’ individual income taxes only after the employees have worked in the state for more than 30 days.

Overall ROAM Index Score

Combining these factors yields a state’s overall ROAM Index score. The top overall score goes to West Virginia with a score of 28.95 out of a theoretical possible total of 35 points. West Virginia scores highly due to its gold-standard 31-day threshold for withholding, exempting nearly 95 percent of incoming commuters with reciprocity agreements, and a relatively high filing threshold.

There is a steep drop-off after West Virginia, with the next-closest state, North Dakota, scoring 17.87 on the ROAM Index. Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin round out the top 5 states.

Only two states receive a negative score on the ROAM Index: Delaware in last with -3.10 and Nebraska in second-to-last with -2.57. Both states are punished for their convenience of the employer rules and, unlike fellow convenience of the employer states like Pennsylvania and New York, do not have redeeming scores in other sections to get out of the red.

The state in third-to-last, Arkansas, is notable for maintaining a poor score despite repealing its convenience of the employer rule in 2021. Repeal of the state’s convenience of the employer rule brought the state out of the red on the ROAM Index, but clearly more work is needed. New York and Mississippi round out the remaining bottom 5 states.

Conclusion

States cannot keep their heads in the sand and pretend that the economy is not changing. Tax policies play a major factor in residency decisions, and remote work will likely accelerate tax migration. States can either resist the trend and bleed taxpayers, or embrace it and work to become competitive.

States can view the state of scores on the ROAM Index as an opportunity. Only West Virginia truly scores well in all sections, and the board is open for other states to become more attractive destinations for remote and mobile workers by passing common-sense laws to protect individuals and businesses from burdensome tax obligations arising from flexible work arrangements. Many of these reforms can be done at minimal revenue cost.

States scoring poorly on the ROAM Index should take it as a wake-up call that they are at risk of shutting themselves off from a digitizing economy. The quickest way to stifle the benefits of remote work to taxpayers would be a race to the bottom on policies such as convenience of the employer rules that seek to rewrite reality on where taxpayers are working.

1 North Dakota and Utah technically have a 21-day filing threshold, but it only applies to states with no income tax or that have the same threshold. Additionally, several subsets of employees are exempted from this threshold. Effectively, it is a global threshold.

2 West Virginia earns a 3.5 because its threshold is stricter for single filers than married filers.

3 Virginia residents must commute daily to Kentucky to be covered by reciprocity agreement.

4 Maryland does not extend reciprocity to Pennsylvania residents of local jurisdictions that impose income tax on Maryland residents. This is not accounted for in the percentage reported here.

5 Kentucky and D.C. residents must commute daily to Virginia to be covered by reciprocity agreement.

6 Georgia has a 23-day threshold, which would earn a 4 in this category, but the “5 percent of total wages” threshold is likely to kick in before that, assuming that wages are evenly distributed across the year.