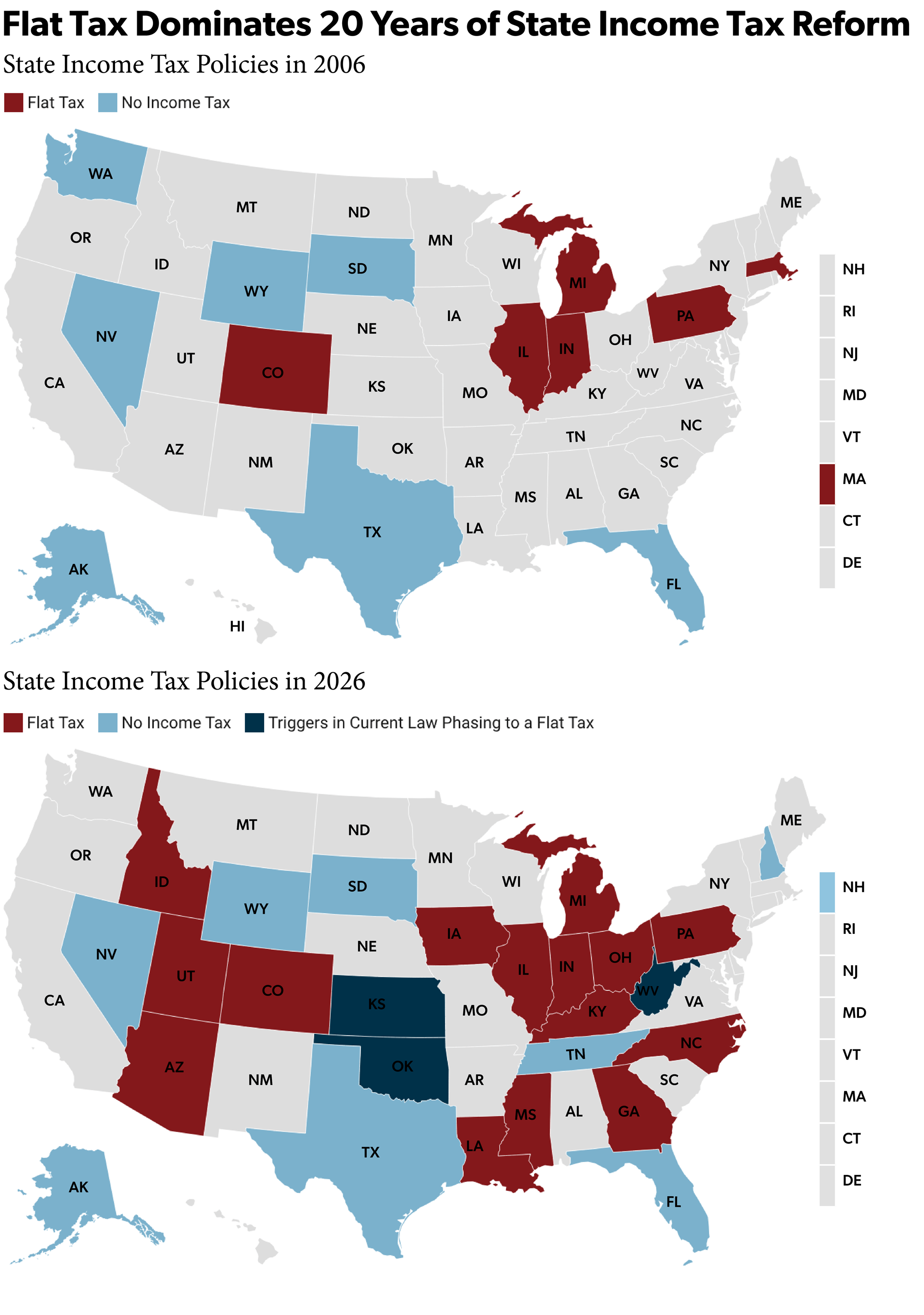

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have reformed their state tax system or otherwise substantially reduced their state taxes in the past two decades, especially in the last five years.[1] These reforms have dramatically changed the landscape of state taxes: in 2006, 13 states either had a flat income tax or no income tax; it is 24 states today.[2]

These state tax reforms have common features: reducing income tax rates and brackets, increasing the standard deduction or a 0% bracket exempting a basic level of income from tax, inflation-adjusting brackets and thresholds, reducing business taxes, and expanding the sales tax to previously untaxed services. Tax triggers, which condition future tax cuts on certain revenue or budget targets, are now commonly used by red and blue states alike to schedule longer-term tax changes while avoiding a sudden state budget crisis.[3]

While this record is impressive, not all state tax overhauls have succeeded. Florida, Kansas, Maryland, Nebraska, and Utah are examples of states where ambitious proposals failed to win enactment, were gutted due to political opposition, or were rolled back after passing. Florida, Maryland, and Nebraska attempted to expand the sales tax base, but also would have imposed sales tax on selected service providers without exempting business-to-business transactions. Kansas cut income taxes on pass-through businesses deeply without using triggers or cutting spending, leading to a budget crisis. Utah’s reform increased sales taxes without much income tax reduction. Some of these lessons were also encountered in states that ultimately passed reforms.

From this record, policymakers should keep in mind ten tips for a successful state tax reform:[4]

1. Start with principles.

Those leading the tax reform effort should lay out a set of uncontested principles, like a desire for a fair, simple, pro-growth tax system. This vision should guide the effort from beginning to end.

2. Listen!

Seek out the advice of taxpayers (and tax administrators), as they often have unique insight into what works and what is possible. If a goal is to attract new jobs and investment, don’t just talk to existing in-state incumbents.

3. Push for broad bases and low rates.

Broad tax bases are best for long-run revenue adequacy and minimizing the effects of economic volatility. The tax code shouldn’t be used to pick winners and losers by giving carveouts to the politically connected and punishing others with multiple, punitive, or special taxes. Rate reductions, if sufficient, can be the tradeoff for losing special tax benefits.

4. Triggers are successful for multi-year efforts.

Making future reductions contingent on hitting revenue or spending restraint targets can ease concern about future budget impacts. Triggers can be based on revenue growth above inflation (Massachusetts), revenue growth above a target with a cap on spending growth (North Carolina), or if spending is less than the prior year’s revenue (Mississippi).

5. Repairs, even revenue-neutral ones, matter.

If a tax system is inequitable, inefficient, complicated, unstable, or insufficient, there are likely flaws in its structure. Examples include selective taxes or carveouts for certain economic activity, lack of inflation-indexing, or hostile tax administration practices. Fixing these can reduce compliance burdens and create incentives for investment and job creation, sometimes even without collecting less revenue. Reform may be less controversial if it is made clear that a goal is repair of the unstable tax structure.

6. Build for the future, not just the now.

A state’s tax system should work for the economy the people of the state want to have, not necessarily the one they have now. A tax system geared toward existing businesses and existing taxpayers may not set up the state for future growth.

7. Keep an eye on the competition.

Cross-state movement of people and dollars is real, and being the only state among your neighbors to do something could be a game-changer or a liability. Ask national experts about recent policy trends in target states.

8. Apply principles to the whole, not just the parts.

Individual components of the tax reform may satisfy one criterion or stakeholder but fall short with others. The reform should be measured as an entire package, not individual parts.

9. Acknowledge the downside.

Transparency means being honest about the “losers” in tax reform as well as the “winners.” Show illustrative taxpayers and how their tax bills will change before and after. Good reform means the good will still outweigh the bad, and that there will be far more winners than losers.

10. Educate.

Complexity of tax issues is one reason that reform is difficult, and misunderstandings are widespread. Opposition can arise just from caution about change from the status quo.

The past two decades of state tax reforms offer roadmaps for success as well as cautionary lessons from missteps. Reforms like North Carolina’s, Iowa’s, and even the District of Columbia’s, which were guided by clear principles, grounded in broad bases and low rates, informed by stakeholder input, and structured with safeguards like triggers, are far more likely to endure and deliver economic benefits. Equally important is a willingness to be transparent, forward-looking, and attentive to competitive pressures, while recognizing and addressing the tradeoffs inherent in any major policy change. When policymakers approach tax reform as a comprehensive, educational, and principled effort, they can design tax systems that are fairer, simpler, and better suited to promote long-term growth.

[1] Arizona (2021-23 flat tax), Arkansas (2022 tax cut), Colorado (2022 tax cut), Connecticut (2024 tax cut), Georgia (2022 flat tax), Idaho (2022 flat tax), Indiana (comprehensive reforms in 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015, tax cuts in 2022, 2023, 2025), Iowa (2018 comprehensive reform, 2022-24 comprehensive reform), Kansas (2012 pass-through exclusion repealed in 2017, 2025 reform), Kentucky (2022 flat tax), Louisiana (2024 comprehensive reform), Michigan (2023 tax cut), Mississippi (2023 flat tax, 2025 reform), Missouri (2025 repeal of capital gains tax), Montana (2025 tax reductions), Nebraska (2023-26 tax cut), New Hampshire (2025 repeal of tax on dividends and interest), New Mexico (2024 tax cut), North Carolina (comprehensive reforms in 2013, 2015, 2017, 2021), North Dakota (tax cuts in 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015, 2023 reform), Ohio (2005 CAT, 2025 flat tax), Oklahoma (2005-06 tax cuts, 2014 tax reform, 2021-22 tax cuts), Pennsylvania (2022 comprehensive reform), Rhode Island (2010 comprehensive reform), South Carolina (2022 tax cuts), Tennessee (2016-21 Hall tax repeal), Utah (2006-07 comprehensive reform, 2019 further reform repealed in 2020), West Virginia (comprehensive reforms in 2008 and 2023), Wisconsin (2021 and 2023 tax cuts), and District of Columbia (2014-18 comprehensive reform). Seven additional states have significantly increased taxes in recent years: California, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, and Washington.

[2] Eight states with no income tax: Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming. Sixteen states with flat tax: Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Washington. Additionally, Kansas, Oklahoma, and West Virginia have laws that transition to a flat tax; and Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and West Virginia have laws that transition to no income tax.

[3] Tax triggers were first used in Massachusetts (2002), West Virginia (2008), North Carolina (2013), and District of Columbia (2014), and subsequently in Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, New Hampshire, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina.

[4] These tips are drawn from several sources, including Benjamin Russo, “State Tax Reform: Evidence, Logic, and Lessons from the Trenches,” 39 State Tax Notes 467 (2006); Joseph Henchman & Scott Drenkard, “North Carolina Tax Reform Options: A Guide to Fair, Simple, Pro-Growth Reform” (2013); American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, “Guiding Principles of Good Tax Policy: A Framework for Evaluating Tax Proposals” (2001).