(pdf)

Debates over the State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction continue to take center stage in Washington. Persistent in these debates is the fallacious notion that the states that benefit most from the SALT deduction deserve this special tax code treatment because they are “donor states.”

But there is no such thing as “donor states,” only “donor taxpayers.” States that have more taxpayers benefit from the SALT deduction than others do so entirely because they have wealthy taxpayers and we have a progressive tax code (that most SALT defenders would wholeheartedly advocate for).

SALT deduction advocates from high-tax states are engaging in a classic case of wanting to have their cake and eat it too. While they want high progressive federal and state tax rates that take in large amounts of state revenue from the wealthy, they don’t want the backlash when those overtaxed individuals choose to pack up and leave for greener pastures. They seek to square this circle by providing those taxpayers with a hefty discount on their state and local tax burdens by allowing them to deduct those high tax bills on their federal income tax returns.

But while the SALT deduction prevents some of high-tax states’ and localities’ tax burdens from hitting wealthier taxpayers directly in the wallet, it doesn’t make that burden disappear. The federal government, and the taxpayers who fund it, instead take it on. It’s a shell game that leaves average taxpayers in other states as the losers.

Background: SALT and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, taxpayers who itemized their deductions (i.e. did not take the standard deduction) could deduct unlimited amounts of certain state and local taxes paid on their federal income tax return. The deduction was massively skewed to benefit the wealthiest taxpayers, with over 84 percent of the benefit flowing to taxpayers making over $100,000 per year.

As part of the TCJA’s efforts to simplify the tax code, the SALT deduction was capped at $10,000, while the standard deduction was doubled. TCJA also repealed the Alternative Minimum Tax, a parallel tax on those taking too many deductions (including SALT).

Consequently, the number of taxpayers claiming the deduction in tax year 2019 dropped to 16.4 million, as compared to 46.6 million before the cap. But more taxpayers also benefited from the increased standard deduction without having to itemize — about 30 percent of taxpayers itemized deductions before the TCJA compared to around 10 percent afterwards.

The loss of the SALT deduction was not a significant hit to taxpayers, particularly considering the capping of the SALT deduction took place in the context of other changes to rates and deductions. The Tax Policy Center estimates that over 80 percent of taxpayers received a tax cut thanks to the TCJA, while less than 5 percent received a tax increase.

Nevertheless, lawmakers in the 118th Congress have introduced numerous proposed changes to the capped SALT deduction, ranging from doubling the cap from $10,000 to $20,000 to retroactively fully restoring the deduction all the way back to 2017 and providing refunds to taxpayers for the value of the deduction for tax years since 2017. The 2021 Democratic House passed omnibus spending legislation that would have raised the SALT cap to $80,000, though this failed to pass the Senate.

Under current law, the $10,000 SALT cap is set to expire in 2025 along with the other individual income tax portions of the TCJA. Rep. Vern Buchanan (R-FL) has introduced legislation (H.R. 976) to make the individual income tax portions of the TCJA, including the $10,000 SALT cap, permanent.

“Donor States...”

The premise of “donor states” implies that certain states provide more in tax revenue than they receive back in the form of grants and federal spending. Other analyses have tackled the question of whether or not this is true directly, pointing out that seven of the ten states benefiting most from the SALT deduction receive more in federal grant expenditures per capita than the national average.

But it’s worth asking why this matters at all. Nowhere else in our tax code is any effort made to ensure that taxpayers receive back benefits and grants exactly proportionate to their tax burden — even programs like Social Security where benefits are determined by taxpayers’ contributions benefit less wealthy taxpayers disproportionately. Why would this be any different for states with higher-than-average per capita incomes?

…Or “Donor Taxpayers?”

In fact, the progressivity of our tax code is underpinned by the idea that wealthier taxpayers should contribute more than lower-income taxpayers. There’s little reason to insert an asterisk if groups of wealthier taxpayers happen to live in the same state.

NTUF’s “Who Pays Taxes” series has consistently found that the tax code is highly progressive, with taxpayers in the top 1 percent of income earners paying 42.3 percent of federal income taxes despite earning 22.2 percent of adjusted gross income (AGI) — a nearly 2:1 ratio.

The rhetoric of SALT advocates consistently suggests that the capping of the SALT deduction affects the middle class just as much as wealthy taxpayers. According to the Tax Policy Center, increasing the SALT cap from $10,000 to $80,000 as proposed by House Democrats in 2021 would have seen about 70 percent of the benefit go to the top 5 percent of income earners.

Legislators from states that benefited most from the uncapped SALT deduction would undoubtedly argue that those national-level statistics look different within their states. So it’s worth examining what state/local tax bills look like in specific states.

To do this, we will look at the four states with the highest percentage of SALT benefits claimed as a percentage of AGI: California, Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York.

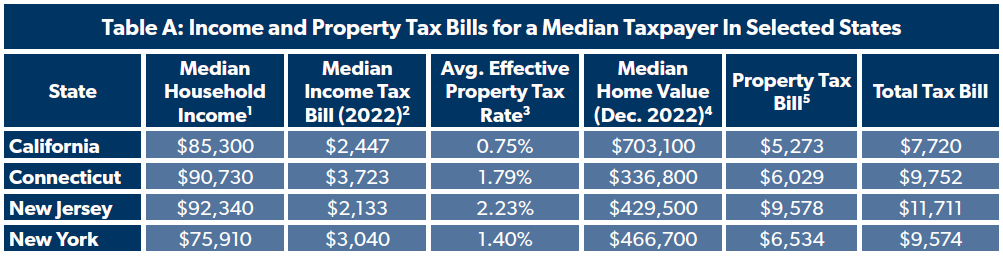

In Table A, we look at the tax bills of taxpayers in each state earning the median household income and owning a home valued at the median home value in the state at the end of 2022. We will assume the taxpayer is married, files jointly, and has one dependent child. As taxpayers cannot claim SALT deductions for both their income and sales taxes at the same time, we will assume the taxpayer chooses to deduct their income and property taxes.

Only in one of these states (New Jersey, the highest-taxed state in the nation), is this hypothetical median taxpayer affected by the existing $10,000 cap on the SALT deduction. Even here, the inability to claim the remaining $1,711 in taxes paid on federal income tax returns works out to just over $200 in additional tax liability.

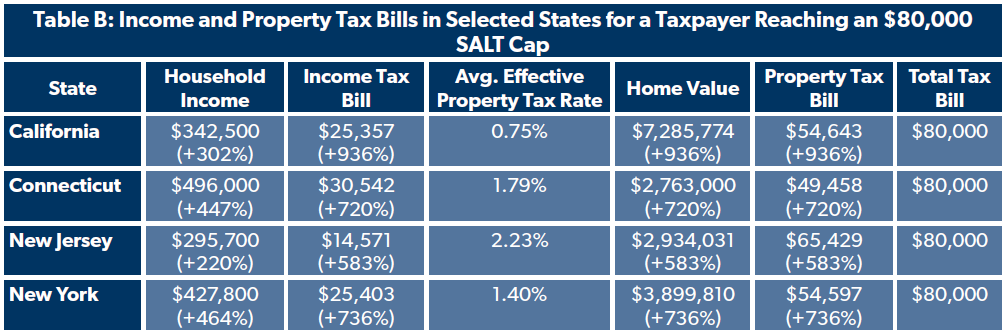

But what would a taxpayer able to take advantage of the full $80,000 SALT deduction proposed under House Democrats’ 2021 package look like? Table B calculates the necessary household income and home value in each state to reach this point, assuming the ratio of income taxes to property tax remains equal. Percentages indicate the percent increase over the state median.

Of course, the ratio of home value to household income may not remain precisely constant. But the point remains that even in these four states, a taxpayer able to claim $80,000 in SALT deductions likely has a multi-million dollar home and is earning several times the state median income.

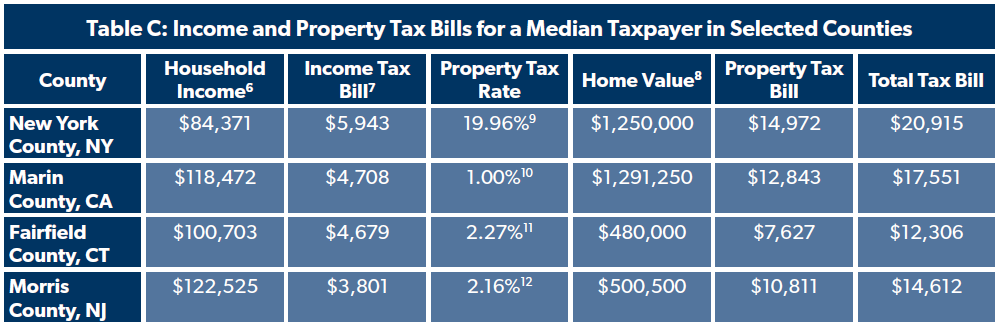

Some may argue that even state-level data is too broad, and that the SALT deduction is important to a few specific counties. Setting aside the absurdity of basing federal income tax policy on the specifics of a few counties, we will run the same calculations for the counties in each of the four above states that benefited most from the SALT deduction prior to its capping.

Table C shows that the median taxpayer does exceed the $10,000 SALT cap in each of these counties, but this is due more to the unusual wealth In these counties than high tax rates. In New York County and Marin County, the median home value exceeds the national median by more than 200 percent. Meanwhile, the median household income is 35 percent higher than the national median in Fairfield County and 64 percent higher in Morris County.

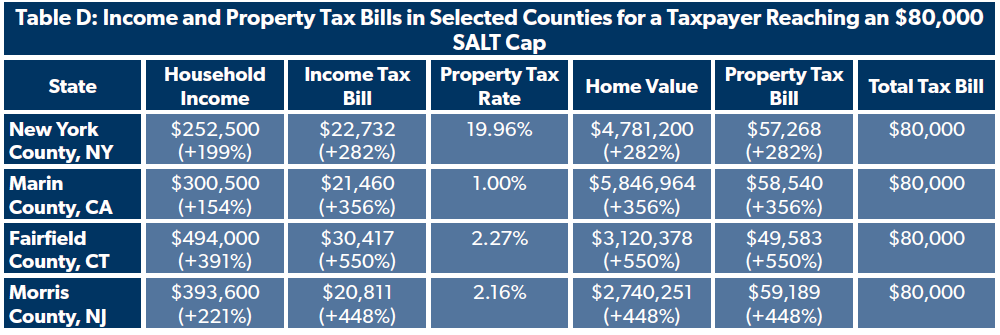

Even so, a taxpayer would have to be far wealthier than average even by these counties’ unusually wealthy standards to take advantage of a full $80,000 SALT cap. Table D calculates the necessary household income and home value in each county to reach this point, also assuming the ratio of income taxes to property tax remains equal. Percentages indicate the percent increase over the county median.

Conclusion

States and counties with more wealthy taxpayers are not “donors,” the taxpayers themselves are. A system of progressive taxation will inevitably result in wealthier taxpayers paying more in taxes — the fact that this may make high-tax states more undesirable to those taxpayers is something that the federal government is under no obligation to ameliorate through the federal income tax code.

Taxpayers should not fall for rhetoric that suggests that the $10,000 SALT cap is a financial concern to any but the wealthiest taxpayers in the country. It’s no more relevant to the middle class than taxes on fuel for private jets.

[1] Sourced from St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data, Real Median Household Income by State for 2022. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/release/tables?eid=259515&rid=249

[2] Author’s calculations, assuming married filing jointly and one dependent.

[3] Calculated using Tax Foundation’s calculations on average effective property tax rates as a percentage of owner-occupied housing value. https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/state/property-taxes-by-state-county-2023/

[4] Data from Redfin, median home value in each state as of December 2022. https://www.redfin.com/news/data-center/

[5] Author’s calculations.

[6] Sourced from FRED county-level median income data.

[7] Author’s calculations, assuming married filing jointly and one dependent.

[8] Data from Redfin, median home value in each county as of December 2022. https://www.redfin.com/news/data-center/

[9] New York County assesses this rate on 6 percent of a home’s market value.

[10] California homeowners are able to deduct $7,000 in home value from their home’s market value.

[11] Connecticut assesses this rate on 70 percent of a home’s market value.

[12] Rates differ by town or borough in Morris County, so the average effective rate was used instead.