(pdf)

I. Introduction

It’s been just over a year and a half since Puerto Rico was devastated by Hurricane Maria. The natural disaster hit the territory hard at a time when it was already reeling from over a decade of economic recession and a long-standing debt crisis. Now, Puerto Rico is at a crucial crossroads as it looks to restore solvency and rebuild its economy. One such track that is seriously being explored is incorporation toward official statehood. In the summer of 2017, Puerto Ricans voted in favor of becoming the 51st state in the union. After the vote, the Governor appointed shadow representatives and senators to petition Congress for statehood. Legislation to establish parameters for Puerto Rico’s incorporation has been introduced in the previous Congress and is expected to be reintroduced this year.

If this process continues forward, there are policies and reforms that both the federal government and the territory’s government would need to coordinate in order to ease the imposition of new federal taxes on Puerto Rico residents and businesses. Yet, such would also be the case even if Puerto Rico’s territorial status is maintained. The twin goals that policymakers pursue should be to lift the U.S. citizens of Puerto Rico while safeguarding federal taxpayers through reasonable, achievable reform benchmarks.

II. Puerto Rico’s Challenges

A. Fiscal & Economic

Puerto Rico’s recession started in the fourth quarter of 2006, pre-dating the onset of the 2008 national economic downturn. Over that span, Puerto Rico’s economy contracted by over 10 percent and it is estimated that its population declined by 300,000 as younger people moved to the mainland United States in search of jobs.

This economic contraction worsened an already overextended budget. Puerto Rico’s government issued bonds in order to finance persistent annual deficits, piling up over $70 billion in debt. Some $48 billion of this amount is the result of borrowing from more than a dozen public corporations. Like too many states, Puerto Rico has also amassed a large unfunded liability for public pensions. Its pension funds have a combined shortfall of $55 billion, and a funding ratio of 8 percent.[1]By comparison, the two states with the lowest funding ratio are New Jersey and Kentucky, both around 31 percent funded.[2]

The situation boiled over in 2015. That June, Governor García Padilla warned during a televised address that “the debt is not payable.”[3]Debt service costs began to consume a greater portion of tax revenues flowing into Puerto Rico’s Treasury, and in August it was unable to make a full interest and principal payment on bonds issued by the Public Finance Corporation.[4]The ongoing financial crisis led to the passage of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Security Act (PROMESA) by Congress in 2016. This legislation provided for a Financial Management & Oversight Board empowered to work with the territory’s government toward setting the island on a path to balance. It also established a legal framework to restructure the accumulated debt. Under the provisions, the Governor produced a fiscal plan to close the budget gap which was approved by the Board in the spring of 2017. The Board then initiated a PROMESA-created bankruptcy process in conjunction with creditors to begin to restructure the debt load.

Puerto Rico’s challenges were already extremely difficult and were intensified by Hurricane Maria, which decimated homes, businesses, and basic infrastructure, further straining a fraught financial situation. In its annual survey of Puerto Rico’s business climate, the New York Fed found that 77 percent of small businesses reported losses due to the hurricane. The costs took a toll: only 4 percent of businesses had their losses fully covered, and just 23 percent had them partially covered.[5]Puerto Rico’s government estimated that the storm caused over $94 billion in damages. To assist with the recovery, Congress authorized $32 billion in federal aid in October 2017.[6]

Although the mass disruption of communications networks and the destruction of infrastructure slowed the disbursement of funds, Puerto Rico is making progress in rebuilding. Its Treasury Secretary Teresita Fuentes recently announced that net revenue to the island’s general fund totaled $858 million in December – a $158 million improvement from a year ago.[7]Improvement in receipts throughout the year were due in large part to the influx of contractors and widespread recovery efforts.

B. Puerto Rico’s Territorial Status

Puerto Rico became a territory in 1898, its residents were granted U.S. citizenship in 1917, and Congress approved its constitution in 1952. Its territorial status has played a role in its economic development, which has come with a mix of advantages and disadvantages.

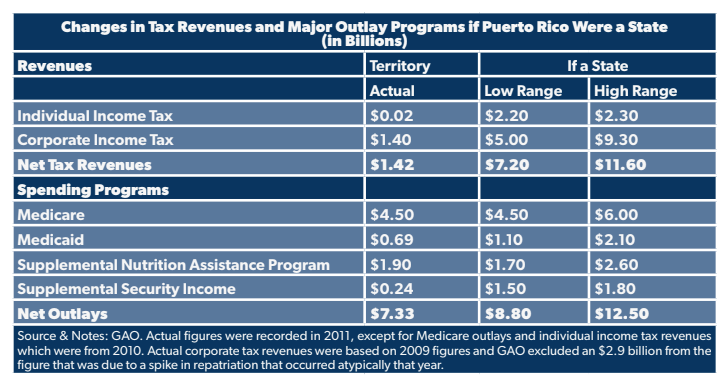

Residents are exempt from the U.S. federal income tax on income earned in Puerto Rico but are liable for taxes on income earned outside of Puerto Rico. In 2014, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that if Puerto Rico were a state, individual income tax receipts would have risen from $20 million to up to $2.3 billion.[8]

Residents are not eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit. To qualify for the Child Tax Credit, a resident must have three or more qualifying children, a higher threshold than in the states. In 2016, a report estimated that equalizing these tax credits would increase transfers to Puerto Rico by $1 billion per year, a combination of higher tax credits and for outlays via the “refundable” portion of the credit which can be claimed regardless of one’s income tax liability.[9]

Citizens pay into Social Security and have access to Medicare and Medicaid, but instead of being eligible for Supplemental Security Income assistance, low-income, elderly and blind or disabled people can get help from a similar program run by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In 2014, GAO reviewed how selected federal spending programs would be impacted under statehood and estimated that outlays would have been from $1.5 billion to $5.2 billion higher.[10]

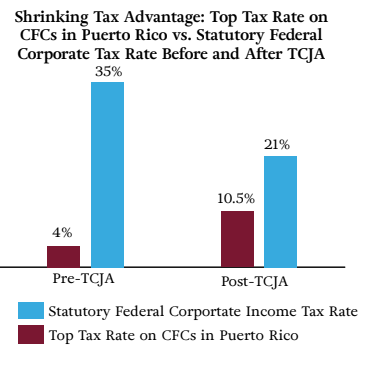

U.S.-owned corporations operating in Puerto Rico have their island-sourced income treated in the Tax Code as foreign earnings when the companies are organized as Controlled Foreign Corporations (CFCs). This conferred a tax advantage to U.S. corporations operating in Puerto Rico versus one of the fifty states where they would be subject to the federal corporate tax rate. GAO estimated that if Puerto Rico were a state, corporate income tax collections in FY 2011 would have been $3.6 billion to $7.9 billion higher.[11]However, this tax advantage was narrowed as a consequence of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).

C. Tax Reform and Puerto Rico

Before passage of the landmark tax reform bill at the end of 2017, the U.S corporate tax rate was a hefty 35 percent. Having the highest statutory rate in the industrialized world hurt the nation’s competitiveness and sent jobs, and tax revenues, abroad.[12]To stem this outflow the TCJA cut the corporate tax rate to 21 percent. The law was also designed to encourage domestic investment. The Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) section of the TCJA made it more expensive for U.S. corporations to operate CFCs overseas. The complicated provision assesses an effective tax rate of 10.5 percent through 2025, rising to 13.125 percent thereafteron a CFC’s profits earned from “intangible” intellectual property assets such as trademarks, patents, and copyrights.[13]Those companies that manage to escape GILTI might instead face the Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT), which hits income flowing the opposite way: from U.S. parents to foreign-based companies (at a rate of 10 percent through 2025 and 12.5 percent thereafter). There is also a new Foreign-derived Intangible Income (FDII) tax with an effective rate of 13.1225 percent (rising to 16.83 percent in 2026) on earnings from intellectual property held by foreign companies (including CFCs in Puerto Rico with parent firms in the rest of the U.S.).

Calculating the loss of Puerto Rico’s corporate tax advantage over U.S. states remains somewhat speculative, given the fact that the U.S. Treasury Department has yet to issue all the rules surrounding GILTI and other provisions that could seriously affect how CFCs in Puerto Rico are supposed to report income. One way of looking at the problem would be to compare the top rate on CFCs in Puerto Rico to the statutory federal rate prior to TCJA (4 percent vs. 35 percent) and after TCJA (10.5 percent vs. 21 percent).

This does not account for additional shrinkage in the tax advantage from the GILTI rate bump-up after 2025 to 13.25 percent, nor whether a given company faces BEAT or the FDII instead. Another way would be to utilize effective rates after deductions and credits. This is a difficult proposition, since different industries face different circumstances that affect their final tax bills.

Regardless, as it stands, the provisions described above will impact U.S. businesses that operate in Puerto Rico in varied ways. The pharmaceuticals and medical equipment and supplies industries, whose business models are heavily-dependent on intellectual property, comprise about one-third of the tax base. Puerto Rico’s anomalous status in the Tax Code as a foreign jurisdiction was not adequately considered when these reforms – which were designed to bolster the U.S.’s global competitiveness – were enacted.

Estudios Técnicos, a Puerto Rico-based economic and planning consultancy, projected that the number of plants operating in the territory will decline because of the tax changes:

This will probably not lead to an immediate and massive exodus of firms from Puerto Rico but it will impact future promotions and generate a slow erosion in their presence …[14]

But is this prediction too pessimistic? Opinions vary. In December 2017, around the time of TCJA’s passage, Senator Marco Rubio told reporters in an interview that:

We’ve not heard from a single company, and in fact, every one of these entities involved in Puerto Rico has told us they’re in favor of the tax bill,” Rubio said in an [sic] year-end interview with reporters. “And a few have told us – especially on the pharmaceutical side – that their general sense of it is that moving would make no sense, because it's not clear that there’s any other jurisdiction in the world that’s more advantageous logistically and from a tax perspective.[15]

A contrarian view of Estudios Técnicos’ concerns over the shrinking business tax rate differential between Puerto Rico and the mainland U.S. is that it provides public officials with greater encouragement to comprehensively reform the way business on the island is taxed. Indeed, in this respect statehood advocates could argue that TCJA has given impetus to make Puerto Rico more attractive for new investment as well as retaining current jobs, beyond what the CFC regime could possibly sustain. Other analysts contend that the GILTI, BEAT, and the 12.5 percent IP tax spread pain to many jurisdictions, to the point that Puerto Rico may not be at such a large disadvantage after all. As a recent CNN article put it:

Some experts say the 12.5% tax won’t trigger a corporate exodus off the island. They argue that it won’t make sense for companies to leave if they face the same tax in another country. And if firms move their operation to the mainland, they’ll have to pay the new corporate rate of 21%.

“This tax legislation is not intended to hurt the island,” says Cate Long, co-founder of the Puerto Rico Clearinghouse, a research firm that focuses on the island’s debt crisis. “It’s still cheaper on a tax basis to operate offshore,” in Puerto Rico.[16]

Even those with a rosier post-TCJA outlook would likely acknowledge that unless Washington and San Juan work toward additional reforms of their tax systems, the outlook for Puerto Rico is bleak. There is still time to act, but the clock is ticking. Eli Lilly CEO Dave Ricks reflected this balanced view when earlier this year he told Bloomberg, “Absent some change, it will become economically more difficult through time. We don’t have any changes planned, but I’m worried for the island in that regard.”[17]

More than a decade ago, Tax Code Section 936 was phased out. Originally enacted in 1976, this provision let subsidiaries of U.S firms to pay no federal taxes on their profits in Puerto Rico. Some have argued that the phase-out stripped away a major competitive edge for Puerto Rico with federal business taxes, contributing to the economic downturn that afflicted the island for longer than the Great Recession in the rest of the U.S.[18]Others counter that with the loss of the carve out, U.S. firms simply adopted CFC status, keeping nearly all of the 936 tax credits and that drop in employment on the island was due to other factors, such as the ending of several health care patents and increased automation.[19]These competing theories about Section 936 are a result of the tax code uncertainty facing Puerto Rico and its impact on economic uncertainty.

Left unaddressed, the unintended consequences of policies on both sides of the Caribbean again threaten to further erode Puerto Rico’s tax base. It is therefore important to seize every opportunity for the island with TCJA as well as subsequent tax legislation that may be considered in Congress. These are discussed below.

III. Opportunities & Challenges on the Path to Statehood

In June of 2017, Puerto Rico held a non-binding referendum to decide whether to incorporate as a new state in the union. Although only 23 percent of Puerto Ricans voted, the results found 97 percent of voters in support of statehood. Scientific polling conducted in Puerto Rico tends to show that strong majorities of residents believe that resolving the island’s political status (whether as a territory, state, or independent nation) is an issue of primary importance. Several previous referenda held in the 50 years preceding 2017 have shown divisions over these three options, but generally statehood has been slowly gaining in popularity.[20]A nationwide survey of American adults by Rasmussen Research found that a plurality (47 percent) supported statehood for Puerto Rico, but these margins have fluctuated in the firm’s previous polls.[21]Nonetheless, political momentum among leaders of Puerto Rico’s current governing party for statehood is strong, meaning that the fiscal implications of the issue are no longer as remote for taxpayers as they might have been previously.

The process of creating a new state is outlined in Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution, but does not provide a great deal of specificity:

The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States; and nothing in this Constitution shall be so construed as to Prejudice any Claims of the United States, or of any particular State.

After a territory votes in favor of statehood, the next step is to petition Congress for admission into the Union. Typically, a territory sends shadow representatives and two senators to lobby for statehood. After a territory files a petition there is no set process for granting statehood, Congress can determine the process for each petition on a case-by-case basis, considering factors such as the political viability, historical conditions, and fiscal situation of the territory. A majority vote would be required in the House and Senate to pass a joint resolution, and of course, it would require the President’s signature. This process allows for flexibility to craft a plan that works for the territory and taxpayers alike.

As noted above, Puerto Rico faces many significant challenges. Its median income ($19,606[22]) is about a third of national U.S. average ($59,055) and over 44 percent of the population is below the federal poverty level.[23]In August, the national unemployment rate stood at 3.9 percent[24]while in Puerto Rico, struggling with the aftermath of the decade long economic contraction and Hurricane Maria, unemployment still tops 9 percent.[25]On the positive side, this is a 2 percentage point improvement from a year earlier.

Puerto Rico’s leaders have pursued statehood as a means to improve its economic condition so that residents don’t have to flee the island in search of gainful employment. As Estudios Técnicos noted, “It shouldn’t be easier for Puerto Ricans to find work in Florida and Texas than at home.”[26]Supporters of statehood point to the historical example of Hawaii and Alaska, which each averaged double-digit economic growth for more than a decade after admission. As the GAO stated, “statehood could eliminate any risk associated with Puerto Rico’s uncertain political status and any related deterrent to business investment.”

For Puerto Rico, this process would be an opportunity for federal and regional governments to coordinate efforts to: reform and simplify the tax system, stem and eventually reverse the erosion of Puerto Rico’s tax base, reduce unemployment and increase labor participation, and set a course for long-term economic growth. This would help restore investor confidence in Puerto Rico, make it easier to resolve the long-standing debt crunch, and secure a path to a sustainable solvency.

A. Local Government Actions

Although Puerto Rico’s challenges are numerous, the municipal government has moved forward on several reforms following PROMESA’s passage. For example, under the provisions established through PROMESA, the Oversight Board has made progress on a deal with bondholders to restructure debt from the territory’s Sales Tax Financing Corporation (COFINA). The plan, recently approved by the federal judge overseeing Puerto Rico's bankruptcy, would provide for a 32 percent reduction in COFINA’s debt, and more than $17 billion in debt service payments.[27]

Puerto Rico also made important steps to cut red tape. While PROMESA was still being considered in Congress, National Taxpayers Union President Pete Sepp urged the territory to take steps to streamline the permitting process. This would reduce bureaucratic overhead and help spur business development. Last spring, the Governor of Puerto Rico signed the Puerto Rico Permit Process Reform into law. The new law will improve efficiency in the permit process for development and help boost transparency.[28]

1. Tax Reform

State legislatures across the union have been enacting laws to conform their respective tax codes to the post-TCJA federal income tax code. There were changes to many deductions, including the deductibility of state and local taxes. If Puerto Rico were to become it a state, it would need also need to conform its tax system to account for certain federal deductions that are not included at the local level and, for example, different treatment of capital gains. There is also a prime opportunity for policymakers in Puerto Rico to improve its economic and fiscal condition.

Late last year, Governor Ricardo Rosselló Nevares signed into a law a tax relief and reform package whose elements include a 5 percent credit for all who are subject to Puerto Rico’s income tax, a 1.5 percentage-point reduction in the home-grown corporate income tax rate, a reduction in the sales tax rate on prepared food to 7 percent, and a new exemption from certain business levies for entities with less than $200,000 in annual receipts. The Rosselló Administration’s latest Revised Fiscal Plan, however, is facing questions from the Oversight Board, including concerns about its revenue assumptions, the absence of pension reform, and the addition of “new policies that are inconsistent with PROMESA’s mandate.”[29]This immediate controversy aside, what areas of tax law should Puerto Rico’s policymakers examine most closely?

Corporate and Individual Taxes

Puerto Rico would need to make its business tax system more competitive with the states. It currently assesses a base rate of 20 percent with a graduated surtax added on up to a total maximum nominal rate of 37.5 percent – even higher than the U.S.’s rate before the TCJA – putting it among the highest rates in the industrial world. It follows that this is also far higher than any state. Iowa levies the highest top corporate tax rate at 12 percent, followed by Pennsylvania 9.99 percent) and Minnesota (9.8 percent).[30]

Puerto Rico does offer a number of tax incentives designed specifically to provide relief from federal taxes. Chief among them is Act 20 of 2012. This provides tax incentives for export services to set up shop or expand on the island. It also provides credits and exemptions for research and development and other operational costs. These carve-out special breaks for certain businesses that can cut the rate to as low as 4 percent.[31]To attract new residents, Act 22 of 2012 makes newcomers who live on the island for at least 183 days of the year eligible for tax exemptions on income derived from dividends, interest, and certain capital gains.

With the creation of the Opportunity Zones in the TCJA, lawmakers might reconsider whether these special carve-outs are still necessary. An ideal tax system is one that is low, flat, and equitable for all. If the Opportunity Zones are successful in attracting investments to the island, Puerto Rico would be provided breathing room to phase-down the breaks for targeted businesses.

Alternative Minimum Tax

Alternative minimum taxes (AMT) require certain filers to calculate their tax obligation a second time under a separate system of allowable credits and deductions.In Puerto Rico, the AMT applies to “alternative minimum net income at a 30 percent rate, and may be reduced by the alternative minimum tax credit for foreign taxes paid.”[32]In 2015, Puerto Rico increased the Tangible Property Component of the AMT, imposing “a tax on the value of property transferred to an entity doing business in Puerto Rico from a related party outside of Puerto Rico.” This hit Walmart with a tax liability on over 90 percent of its income, compelling the company to file a lawsuit against the excessive rate. The First Circuit Court determined that the amended AMT “is a facially discriminatory statute that does not meet the heightened level of scrutiny required to survive under the dormant Commerce Clause.”[33]

At the federal level, the TCJA’s reforms repealed the corporate AMT while greatly reducing the impact of the individual AMT, Puerto Rico should follow suit.

Gross Receipts Tax

In addition to the corporate income tax, Puerto Rico also imposes a gross receipts tax. Unlike a sales tax, which the buyer pays directly and the seller collects and remits, a GRT is essentially hidden in price of goods and services because the seller must calculate and pay the charge. Because of the lack of transparency, gross receipts taxes are generally considered to be more economically harmful than sales or income taxes.[34]According to the Tax Foundation, Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington assess a gross receipts tax instead of a corporate income tax, and only two states, Delaware and Virginia, assess a gross receipts tax in addition to corporate income taxes.[35]Puerto Rico should abolish its onerous gross receipts tax.

Sales and Use Taxes

In 2015, Puerto Rico’s sales and use tax rate was increased from 7 percent to 11.5 percent (the 2018 tax reform reduced the sales tax on prepared foods back to 7%). This tops the highest rate seen in the states. Tennessee currently has the highest average combined state and local rate, at 9.46 percent, according to the Tax Foundation.[36]States whose governments are interested in high growth tend to keep other types of taxes low as compensation. States like California that have high sales as well as income and business takes pay a penalty in lower prosperity. Thus California was ranked 47th in the 2018 edition of the Rich States, Poor States: ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index.[37]

Local leaders have recognized that the high rate has negative consequences. The budget plan released in April 2018 would reduce the sales tax back to 7 percent.

Property Taxes

The Council on State Taxation and the International Property Tax Institute have published a worldwide scorecard entitled The Best and Worst of International Property Tax Administration, in which Puerto Rico received an overall grade of “D” for its practices. The composite rating considered many factors. Puerto Rico received “A” grades in the consistency of its forms and compliance deadlines but was awarded “F” grades for items such as unequal assessment ratios and a disproportionate burden of proof on taxpayers.[38]

A tax structure that encourages more business activity in Puerto Rico could help to raise business property values and provide an opportunity for reexamining the entire assessment process for real estate and personal property taxes. Puerto Rico has not conducted a general reappraisal of property taxes since 1958. This is not unique to the territory: several U.S. states, among them New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, have no set reassessment cycle for their localities. All are characterized by heavier than average property tax burdens.

Rather than implementing a regular reassessment as simply an opportunity to fill government coffers with more revenues, the point of periodic reappraisal is to ensure accuracy, transparency, and public confidence in the entire property tax system. Over the long term, these factors lead to better voluntary compliance and more stable collections that are still sufficiently responsive to market conditions.

2. Spending & Regulatory Reform

The decades long-crisis has already made it difficult for Puerto Rico to issue more debt, but if it were to become a state, it would lose a tax advantage for bonds. Currently, the debt issued by Puerto Rico’s government, subdivisions, or public corporations are not subject to income tax. Under statehood this “triple exemption” would no longer apply, leading to further reduced demand for Puerto Rico debt.[39]If it wasn’t already clear, this is just an extra reminder for the necessity of reducing spending as a component of balancing the budget.

Strengthen the Balanced Budget Requirement

A local organization is calling for a comprehensive audit of Puerto Rico’s debt, arguing that more than half of the debt that was issued was done so in violation of its constitution.[40]The territory’s constitution contains what appears to be a robust requirement that “appropriations” in a given fiscal year “shall not exceed total revenues, including available surplus, estimated for said fiscal year, unless the imposition of taxes sufficient to cover said appropriations is provided by law.” Unfortunately, this language was subsequently translated into irrelevance. David R. Martin, who has written several books about Puerto Rico’s economic situation, recounted in The Hillhow, in 1974, Puerto Rico’s Attorney General interpreted earlier debates over this section as justification to embrace a Spanish-language iteration of “total revenues” that carried the meaning of “total resources” – thereby enabling receipts from government bonds to satisfy balanced budget strictures.[41]

Moreover, Martin explained how Congress made the “monumental mistake” of allowing Puerto Rico’s separate debt ceiling law to be weakened over 50 years ago. Because of further questionable practices, such as new borrowing through “appropriation debt,” the limit has been completely eviscerated. Unlike areas of the continental U.S., taxpayers in Puerto Rico have no standing in court to enjoin evasion of this type.

One approach to ensure that the constitution’s fiscal discipline mechanisms are updated is to convene a joint body charged with ensuring that the original English-language intent of Puerto Rico’s constitutional debt controls is clarified for the Spanish lexicon. Kobre & Kim, the financial investigative firm that was hired pursuant to PROMESA to review the source of Puerto Rico’s debt, recommended amending the constitution so that debt issued by COFINA counts toward the debt limit.[42]

Reduce Waste & Improve Efficiency

The Oversight Board was designed in part on the successful District of Columbia Financial Control Board, created in 1995 to foster better stewardship over the capital city’s finances. The city government of Washington, D.C. had amassed a $722 million budget deficit it 1994, and with its bond rating reduced to junk status, it was unable to borrow funds to cover all its operating expenses. The D.C. Financial Control Board helped to contain the debt and address mismanagement before was dissolved in 2001 once the budget was balanced for the fourth consecutive year. But to date the Puerto Rico Oversight Board has not been as effective as the drafters of PROMESA envisioned in overseeing reforms of spending or loosening regulatory burdens on employers.

Financial control boards are intended to work free of political pressures, with a focus on fixing the long-term problems that led to their creation. Like the DC Board, Puerto Rico’s has faced local opposition, but it has been much more rancorous, including an attempted lawsuit challenging its authority. In some cases, the Board has fed local resentment. It caused a controversy over its $60 million budget and the $625,000 annual salary paid to the Executive Director, angering residents who were already concerned about the established of the unelected Board.[43]The Board’s legitimacy was further challenged this February by a federal court ruling that its members were not constitutionally appointed with the advice and consent of the Senate. The ruling did not void the Board’s actions, but may prompt changes to its composition. The President has 90 days to either validate the appointments or reconstitute the Board.

The Oversight Board’s revised Financial Plan, which was unanimously approved in October 2018, projects a $30 billion surplus over the next 15 years. However, this amount is derived from positive macroeconomic feedback including the net economic impact resulting from $87 billion in expected federal and private disaster aid.[44]To adhere to this goal, it is imperative that the Board work with the territorial government to improve management and coordination. Moreover, all spending must be carefully reviewed. Local lawmakers should conduct a full evaluation of all government spending programs for efficiency and effectiveness ‒ providing for public availability and scrutiny of program data so that a comprehensive review is made before programs are automatically reauthorized.

The Oversight Board provided a notable example of this transparency function. In November 2018, the Board issued a warning on a pension spiking attempt. A bill introduced in Puerto Rico’s Senate would allow around a dozen mayors to retroactively enroll in the older, more generous Employees Retirement System instead of its more frugal successor, known as System 2000. Oversight Board Executive Director Natalie Jaresko warned that this bill is inconsistent with the certified Fiscal Plan for Puerto Rico, and that allowing a “select group” to participate in have access to a plan with larger benefits would “create a dangerous precedent.”[45]

Lawmakers should consider the sunsetting of programs, with Texas an example where programs are regularly subject to a rigorous assessment. Similarly, grants should be awarded on an open competitive basis to yield the most effective results for taxpayers. The government should continue to expand opportunities for cost-savings through Puerto Rico’s Public Private Partnerships Authority. Enhanced whistleblower protections would help safeguard these processes by making it easier for employees to report incidences of waste or wrongdoing without fear of reprisal. In addition, this could help address transparency concerns under a law enacted this year to privatize the power grid and expedite the design and approval of contracts.[46]

B. Federal Actions

There are also a number of policies that the federal government could utilize to safeguard the incorporation process, including reforms to encourage economic expansion by easing regulatory burdens.

Transition Period for Taxes

Article I, Section 8, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution stipulates that “all Duties, Imposts, and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.”

H.R. 6246, the Puerto Rico Admission Act of 2018, was introduced in the previous Congress and would trigger a transition process so that Puerto Rico in admitted to the union no later than January 1, 2021.[47]It would establish a task force to report recommendations on federal laws that would need to be either amended or repealed to phase-in equal treatment for Puerto Rico.

If such a bill were to be enacted, a transition period would be needed so that there is not a fiscal shock from tax hikes as the residents of Puerto Rico become fully-subject to federal taxes on individual and corporate income, estate, and gift taxes. Even with the lower rates enacted through the TCJA, the increase in tax liability would be significant.

Residents of Puerto Rico would also become subject to federal excise taxes on motor fuel. Moreover, under the Uniformity Clause, Puerto Rico would lose “cover over,” whereby a portion of the federal receipts from excise taxes, notably for sales of rum imported to the states, are transferred to the Puerto Rico Treasury. This is currently an important revenue source for the island.

Set Achievable Benchmarks Towards Solvency

A similar phase-in would be required to address federal taxpayer concerns on the spending side of the budget ledger, with outlays to Puerto Rico increasing incrementally until parity with other states is reached. As noted above, Puerto Rico would become eligible for an increase of more than one billion dollars through federal entitlement programs. There would also be a significant increase in outlays for “refundable” benefits under the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit that can be claimed regardless of a filer’s income tax liability.

Moreover, it may be necessary to include benchmarks as part of the transition process to ensure that the government of Puerto Rico continues on the path towards a sustainable fiscal position while paying down its debt obligations. The federal government itself is no paragon of fiscal virtue and certainly there are states such as Illinois that need to address their own massive unfunded pension liabilities, but whatever Puerto Rico’s governing status may be, Congress has a special responsibility to island and mainland residents in crafting specific fiscal remedies that set the proper precedents and avoid future crises of far greater magnitude.

Beyond fostering economic growth, there is no more urgent policy priority for reaching long-term solvency in Puerto Rico than controlling government pension obligations. As mentioned previously, the retirement system for Puerto Rico’s government employees operates at a paltry 8 percent ratio of funding. By contrast, an analysis from the National Association of State Retirement Administrators determined that the funding minimum investment agencies, federal regulators, and other entities consider to be healthy for a pension plan is 70-80 percent.[48]

As with any retirement system, changes to Puerto Rico’s structure (including increases in the retirement age, revisions to benefit formulas, and increases in contribution rates) will need to occur gradually. The five-year fiscal plan, a source of constant friction between the Oversight Board and the territorial government, is only the beginning of this process. Should incorporation ever be approved, the progress of such reform would likely be hastened if the path to statehood were conditioned on reaching an established funding ratio based on Governmental Accounting Standards Board or another credible entity. Setting a minimum ratio of 70 percent to be achieved within 10 years would be an ideal target, but its feasibility would depend upon other tax and budget policies functioning as intended. At the very least, a state of Puerto Rico ought to be able to exceed the average for the bottom third of states’ plans, which a recent survey from the Center for State and Local Government Excellence put at 55 percent.[49]

Tax Reform

Initial predictions about the effect of TCJA on Puerto Rico’s economy were often skeptical, and not without reason. Nonetheless, some positive aspects of the law have revealed themselves last year during its implementation.

Among those positives was the creation of Opportunity Zones with tax breaks to spur investment in distressed communities. Low taxes across the nation are the best option for broad-based economic growth, but practical realities recommend targeted enterprise zones for regions facing acute challenges. This past April, Puerto Rico was designated as an Opportunity Zone – one of the first of 18 U.S. entities qualifying for such status at that time. Unlike states, however, virtually the entire territory of Puerto Rico, rather than only certain communities on the island, received the designation. This distinction is important and could bode very well for an economic resurgence. Investors who choose to commit resources to genuine business and economic activity inside Puerto Rico receive: deferral on any capital gains accrued on money they roll over to Opportunity Zones, a 15 percent step-up in basis (subject to certain restrictions), and a 0 percent capital gains tax rate on Puerto Rico-base earnings once a long-held asset is sold.[50]Qualified Zones retain the designation for ten years.

Estudios Técnicos’ analysts have downplayed the potential of Opportunity Zones owing the difficulty of creating the investment infrastructure to support federal rules, but others are more optimistic. As commentators Ryan Ellis and Cesar Conda remarked, Opportunity Zones mean that:

[A]ny investment in Puerto Rico – which is a part of the United States and enjoys the same property rights and other legal protections as anywhere else – is now a tax free activity for those who commit to keep their capital there… Businesses should be eager to set up shop there and provide superior services to the 3 million American citizens still living on the island.[51]

Since Puerto Rico already qualifies for this relief under TCJA, although investors are awaiting clarification from the Department of the Treasury on rules surrounding several Opportunity Zone issues, statehood would perhaps require no more than a technical correction of current statutory law to continue. Yet barring the completion of the incorporation process, Congress will need to enact policies to reduce the unintended disincentives for local investment. One option would be to reduce the U.S. tax rate on Puerto Rico-sourced income, either permanently if Puerto Rico remains a territory, or as a transition during incorporation since presumably companies would not be operating as CFCs in an American state. Whatever the duration of such a rate, it would be desirable to provide Puerto Rico a federal tax climate more hospitable than those afforded our trading partners making foreign direct investment.

Clarity could be applied to the deductibility of Puerto Rico’s 4 percent excise tax. The excise tax was originally established as a temporary measure in Act 154 of 2010, and was extended in 2017. It applies to multinational companies’ purchases of products and services from their Puerto Rico-based subsidiaries. In 2016, the tax raised $2 billion, about a fifth of all general revenue that year. Currently, U.S. companies are able to deduct the amount of their liability for the excise tax from their federal taxes. In 2011, the IRS said it would not challenge any companies that deduct the taxes, but this policy is not set in stone. The IRS left open the possibility that it would reverse this position, but, if so, it would not be applied retroactively. This uncertainty is yet another byproduct of Puerto Rico's hybrid treatment in U.S. tax law.

Others have suggested more directly tying this excise tax with a more straightforward tax on all forms of GILTI and non-GILTI income declared by CFCs. Changing to a more conventional profit tax for CFCs would mean a significant Puerto Rico-level tax hike, but according to supporters of the plan it would allow fuller deductibility against federal corporate liabilities for CFCs and their parents than current TCJA law might provide.[52]Whatever pluses and minuses of this complex strategy, it would only be workable over the long run if Puerto Rico remained a territory, but it could be fashioned as a temporary provision if the island was put on a path to statehood. Federal lawmakers could also simply set a Puerto Rico repatriation rate at a similar or better level to what policymakers included in the TCJA. These provisions would tend to affect companies with a large presence in the territory, and for good reason. These firms, led by the pharmaceutical, retail, and hi-tech industries, comprise the vast majority of Puerto Rico’s tax base and private sector employment. Regardless of the short-term strategies that might be employed to retain job creators in Puerto Rico, the long-run focus must be on clear rules that attract jobs and investment to the island from all sectors and nations.[53]

Finally, the U.S. Treasury should not overlook the chance to take action that could assist Puerto Rico in transforming the tax climate on the island. In 2017, tax expert Ryan Ellis identified a number of “safe harbors” – official administrative guidance that taxpayers can rely on in filing and compliance matters – that the IRS could clarify. Among these were expanding eligibility to use the Schedule C-EZ form for small business filers, creating a simpler reporting procedure for those who rent their property through services such as AirBNB, and streamlining home office deduction rules. Through Executive Order or a Congressional inquiry, the Treasury could be asked to make an inventory of safe harbor options such as these, which might be applicable to Puerto Rico. While most citizens residing on the island are not liable for federal income tax, small and large businesses face numerous federal tax regulations that could be improved.[54]

Jones Act

The antiquated Jones Act requires that any ship traveling between two American ports be built in the United States, owned by American citizens and crewed by American sailors. Because of this protectionist mandate, the people of Puerto Rico and other jurisdictions are suffering from higher shipping costs from the U.S. mainland (and consequently higher prices for goods). In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, the Trump administration temporarily waived the requirement. There is no reason why Americans should be given relief from the Jones Act only when a natural disaster strikes.

This past July, the American Maritime Partnership published a report attempting to claim that the Jones Act has no discernable impact on Puerto Rico’s consumers. However, as Colin Grabow of the Cato Institute, observed, the report had no discernable methodology it basically cherry-picked a handful of retail items.[55]Grabow identified other products whose costs were considerably higher in Puerto Rico compared to the mainland U.S. In a separate article, he also pointed out the Jones Act is getting in the way of Puerto Rico’s energy modernization because there are no ships that meet its requirements that ship liquified natural gas, which is relatively cheaper than coal or petroleum for producing electricity.[56]

Opponents of repealing the Jones Act also frequently point to a 2013 GAO study that found “the effects of modifying the application of the Jones Act for Puerto Rico are highly uncertain.”[57]GAO’s analysts expressed concern over the ability to pinpoint the effect of Jones Act-related mandates, noting that “the impact of any costs to ship between the United States and Puerto Rico on the average prices of goods in Puerto Rico is difficult, if not impossible, to determine with precision.” The report did, however, cite U.S. Maritime Administration statistics indicating that various labor rules surrounding U.S.-crewed ships raised personnel costs aboard vessels to a level five times greater, on average, than for foreign-flagged carriers. Furthermore, despite noting insufficient data to conduct a rigorous analysis, GAO did acknowledge that “shippers doing business in Puerto Rico reported that freight rates for foreign carriers going to and from foreign ports are often – although not always – lower than the rates they pay to ship cargo to the United States.”

If there are concerns about the larger impact of repealing the Jones Act, it could be implemented as a pilot program, establishing a limited number of freeports on the island. The impact of repealing or suspending the Jones Act may not be large compared to the effects of tax and pension reform, but would be easily doable.

Minimum Wage Reform

Since 1983, the federal minimum wage has applied to Puerto Rico, in complete disregard of the island’s poverty and unemployment rates relative to the mainland and its island neighbors. Minimum wages boost income for some low-wage earners, but the regulatory mandate also decrease employment opportunities.[58]There is little doubt that the federal minimum wage law contributed to the erosion of jobs in Puerto Rico. Paul Kupiec and Ryan Nabil reported in 2016 that “the mandatory increases resulted in a minimum wage that was greater than 75 percent of the Puerto Rican median wage. And the results were predictably catastrophic for the economy… Labor costs in the Bahamas and Jamaica, two direct competitors for foreign investment, were half of those in Puerto Rico.”[59]

In an open letter to Congress in 2016, NTU President Pete Sepp suggested pro-growth reforms to minimum wage laws:

Immediately granting two proposals to waive future minimum wage hikes for younger workers, and to waive Puerto Rico from the Labor Department’s tougher salary standard for exempt employee status, would be modestly helpful. However, much more sweeping steps are necessary, such as widening the minimum wage waiver to include employees of all ages, or simply allowing the wage to adjust to the regional labor market realities in the Caribbean.[60]

IV. Conclusion: Protecting Taxpayers & Lifting up Puerto Rico

In 1980, Presidential candidate Ronald Reagan, writing in support of statehood for Puerto Rico, noted that one major challenge in this process would be “to integrate the two separate [federal and territorial] fiscal systems in a way that increases opportunity for the average island citizen.” He also identified the need to “advertise the proven secrets of economic growth, upward mobility for the poor, and ultimately, political stability – even as we return to this recipe ourselves: reasonable tax rates, modest regulation, balanced budgets, and stable currency.”[61]Some four decades later, his words continue to provide solid guidance for policymakers.

Congress, the executive branch, the Oversight Board, and Puerto Rico’s government have coordinated in important ways in the wake of the debt crisis and the devastation wreaked by the hurricane. In 2016 a congressional task force wrote that its members believed that “Puerto Rico is too often relegated to an afterthought in congressional deliberations over federal business tax reform legislation.”[62] This was also the case in the process of enacting the landmark TCJA legislation that cut tax rates and reformed many aspects of business tax code. Policymakers now have an obligation to continue to work together to address the unintended impacts of the tax code on Puerto Rico and implement reforms to promote long-term economic growth. As Pete Sepp and Max Trujillo pointed out private investment and economic growth are key to getting Puerto Rico out of the austerity trap.[63]Getting this right will not just help Puerto Rico, but also serve as a model for U.S. states that may find themselves facing similar fiscal challenges.

[1]Bradford, Hazel. “Puerto Rico Board Comes Out for Pension Reform,” Pensions & Investments, April 16, 2018. https://www.pionline.com/article/20180416/PRINT/180419895/puerto-rico-board-comes-out-for-pension-reform.

[2]Loughead, Katherine. “How Well-Funded are Pension Plans in Your State?” Tax Foundation, May 17, 2018. https://taxfoundation.org/state-pensions-funding-2018/.

[3]El Nuevo Día. “Mensaje del Gobernador Alejandro García Padilla sobre situación fiscal de Puerto Rico,” June 29, 2015. https://www.elnuevodia.com/noticias/politica/nota/mensajedelgobernadoralejandrogarciapadillasobresituacionfiscaldepuertorico-2066574/

[4]Austin, D. Andrew. Puerto Rico’s Current Fiscal Challenges, Congressional Research Service, April 11, 2016. Available via: https://www.puertoricoreport.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/CRSReportApr2016R44095.pdf.

[5]Bernal, Rafael. “Analysis: 77 Percent of Small Firms in Puerto Rico Suffered Hurricane Losses,” The Hill, September 27, 2018. https://thehill.com/latino/408819-analysis-77-percent-of-small-firms-in-puerto-rico-suffered-hurricane-losses.

[6]Acevedo, Nicole. “New Bill Pushes for Commission to Investigate Federal Response to Puerto Rico Hurricanes,” NBC News, June 15, 2018. https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/puerto-rico-crisis/new-bill-pushes-commission-investigate-federal-response-puerto-rico-hurricanes-n883341.

[7]Caribbean Business. “Puerto Rico Treasury: December Net Revenue Exceeded Projections,” February 22, 2019. https://caribbeanbusiness.com/puerto-rico-treasury-december-net-revenue-exceeded-projections//.

[8]Government Accountability Office, Puerto Rico: Information on How Statehood Would Potentially Affect Selected Federal Programs and Revenue Sources, Mar 31, 2014. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-31.

[9]MacEwan, Arthur and Hexner, J. Tomas. Including Puerto Rico in the Earned Income Tax Credit and Full Child Tax Credit, Center for Global Development and Sustainability, October 11, 2016. https://heller.brandeis.edu/gds/eLibrary/pdfs/2016_09_Oct_08_Including-Puerto-Rico-in-EITC-and-CTC.pdf.

[10]Government Accountability Office, ibid.

[11]Government Accountability Office, ibid.

[12]Arnold, Brandon. “Where Have All the Corporations Gone?” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, April 12, 2016. https://www.ntu.org/foundation/detail/where-have-all-the-corporations-gone.

[13]Geiger, Melissa. “US Tax Reform: The Good, The BEAT and The GILTI,” KPMG, January 26, 2018. https://home.kpmg.com/uk/en/home/insights/2018/01/us-tax-reform--the-good--the-beat-and-the-gilti.html.

[14]Estudios Técnicos, Inc. Perspectivas: The Federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), January, 2018. https://www.estudiostecnicos.com/pdf/perspectivas/2018/enero2018.pdf.

[15]O’Keefe, Ed. “One Potential Loser in the New GOP Tax Bill: Puerto Rico,” Washington Post, December 20, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/powerpost/one-potential-loser-in-the-new-gop-tax-bill-puerto-rico/2017/12/20/cdf4324a-e5c9-11e7-a65d-1ac0fd7f097e_story.html.

[16]Gillespie, Patrick. “Puerto Rico Governor: GOP Tax Bill is 'Serious Setback' for the Island,” CNN, December 20, 2017. https://money.cnn.com/2017/12/20/news/economy/puerto-rico-tax-bill/index.html.

[17]Koons, Cynthia and Hopkins, Jared S. “Eli Lilly CEO Says Tax Reform May Lead to More Successful Deals,” Bloomberg, January 8, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-01-08/eli-lilly-ceo-says-tax-reform-may-lead-to-more-successful-deals.

[18]Greenberg, Scott and Ekins, Gavin. Tax Policy Helped Create Puerto Rico’s Fiscal Crisis, Tax Foundation, June 30, 2015. https://taxfoundation.org/tax-policy-helped-create-puerto-rico-s-fiscal-crisis/.

[19]MacEwan, Arthur. Quantifying the Impact of 936,Center for Global Development and Sustainability, Brandeis University. May 8, 2016. https://heller.brandeis.edu/gds/eLibrary/pdfs/Godoy-Foreward-May_5_2016_PuertoRico_2.pdf.

[20]Campbell, Alexia Fernández. “Puerto Rico’s Push for Statehood, Explained,” Vox, September 24, 2018. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/1/11/15782544/puerto-rico-pushes-for-statehood-explained

[21]Rasmussen Reports. “Americans More Receptive to Puerto Rico as a State Than D.C.” January 23, 2018. https://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/politics/general_politics/january_2018/americans_more_receptive_to_puerto_rico_as_a_state_than_d_c.

[22]United States Census Bureau. Quick Facts: Puerto Rico. Accessed November 5, 2018. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/pr.

[23]Seeking Alpha. January 2018 Median Household Income,March 1, 2018. https://seekingalpha.com/article/4152222-january-2018-median-household-income.

[24]U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, August 2018. https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000.

[25]Puerto Rico Unemployment Rate, Trading Economics. Accessed November 5, 2018. https://tradingeconomics.com/puerto-rico/unemployment-rate.

[26]Jaresko, Natalie A. “Reforms: Realistic Hope for Puerto Rico,” Estudios Técnicos, Inc., June-July 2018. https://www.estudiostecnicos.com/pdf/perspectivas/2018/junio-julio2018.pdf.

[27]Slavin, Robert. “Puerto Rico Governor Introduces Bill for COFINA Restructuring,” The Bond Buyer, October 11, 2018. https://www.bondbuyer.com/news/puerto-rico-governor-introduces-bill-for-cofina-restructuring.

Pierog, Karen and Ortiz, Luis Valentin, “Holdout Bondholders Join Puerto Rico Sales Tax Debt Restructuring,” Reuters, September 21, 2018. https://uk.reuters.com/article/usa-puertorico-bonds/holdout-bondholders-join-puerto-rico-sales-tax-debt-restructuring-idUKL2N1W70V7.

[28]Ferraiuoli LLC. PR Development: Amendments to the Puerto Rico Permit Process Reform Act, April 5, 2017. https://www.ferraiuoli.com/news/pr-development-amendments-puerto-rico-permit-process-reform-act-2/.

[29]Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico, Letter to The Honorable Ricardo A. Rosselló Nevares, March 15, 2019. https://caribbeanbusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/FOMB-Letter-Governor-Rossello-CW-FP-NOV-March-15-2019.pdf

[30]Scarboro, Morgan. “State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2018,” Tax Foundation, February 8, 2018. https://taxfoundation.org/state-corporate-income-tax-rates-brackets-2018/.

[31]Henderson, Andrew. “Puerto Rico Tax Incentives: the Ultimate Guide to Act 20 and Act 22,” Nomad Capitalist. June 2, 2018. https://nomadcapitalist.com/2018/06/02/puerto-rico-tax-incentives/

[32]Deloitte. “International Tax: Puerto Rico Highlights 2018,” 2018. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Tax/dttl-tax-puertoricohighlights-2018.p df?nc=1.

[33]Herzig, David J. “Walmart and Puerto Rico,” The Surly Subgroup, August 29, 2016. https://surlysubgroup.com/2016/08/29/walmart-and-puerto-rico/.

[34]Ross, Justin. Gross Receipts Taxes: Theory and Recent Evidence, Tax Foundation, October 6, 2016. https://taxfoundation.org/gross-receipts-taxes-theory-and-recent-evidence/.

[35]Scarboro, Morgan. State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2018, Tax Foundation, February 7, 2018. https://taxfoundation.org/state-corporate-income-tax-rates-brackets-2018/.

[36]Walczak, Jared and Drenkard, Scott. State and Local Sales Tax Rates, Midyear 2018, Tax Foundation, July 16, 2018. https://taxfoundation.org/state-local-sales-tax-rates-midyear-2018/.

[37]Laffer, Arthur, Moore, Stephen, and Williams, Jonathan. Rich States, Poor States: ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index: 11th Edition,American Legislative Exchange Council, april 2018. https://www.richstatespoorstates.org/app/uploads/2018/04/2018-RSPS-State-Pages_Final.pdf.

[38]Nicely, Frederick et al. The Best and Worst of International Property Tax Administration, Council on State Taxation, September 2014. https://www.cost.org/globalassets/cost/state-tax-resources-pdf-pages/cost-studies-articles-reports/the-best-and-worst-of-international-property-tax-administration---scorecard.pdf.

[39]Government Accountability Office, ibid.

[40]Jackson, Johni. “Hurricane María & Puerto Rico’s Debt: How Avoiding the Audit Left the Island Unprepared,” Remazcla, September 20, 2018. https://remezcla.com/features/culture/puerto-rico-debt-avoiding-the-audit/.

[41]Martin, David R. “Back Story on Puerto Rico’s Debt Crisis,”The Hill, September 4, 2015. https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/economy-budget/252723-back-story-on-puerto-ricos-debt-crisis.

[42]Kobre & Kim LLC. The Independent Investigator’s Final Investigative Report, August 20, 2018. https://drive.google.com/file/d/19-lauVo3w9MPS03xYVe0SWhQin-Q6FEf/view.

[43]Suarez, Cyndi. “Puerto Rican Lawmakers Say No to Paying the Salaries of Its Rulers,” Nonprofit Quarterly, April 9, 2018. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2018/04/09/puerto-rican-lawmakers-say-no-paying-salaries-rulers/.

[44]Puerto Rico Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority. “Fiscal Plan for Puerto Rico: As Submitted to the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico August 20, 2018 Revision,” August 2018. https://www.aafaf.pr.gov/assets/Fiscal-Plan-for-PR-August-20-2018.pdf

[45] Jaresko, Natalie, A.Email to The Honorable Thomas Rivera Schatz

President of the Senate of Puerto Rico et al., November 12, 2018.

https://media.noticel.com/o2com-noti-media-us-east-1/document_dev/2018/11/12/FOMB%20-%20Letter%20re%20%20PS%201148%20-%20Nov%2012%202018%20FINAL_1542046323662_18525904_ver1.0.pdf.

[46]Kunkel, Cathy. “IEEFA Puerto Rico: A Step toward Renewables or Another Scandal Waiting to Happen?” October 30, 2018. https://caribbeanbusiness.com/ieefa-puerto-rico-a-step-toward-renewables-or-another-scandal-waiting-to-happen.

[47]H.R.6246 - Puerto Rico Admission Act of 2018. June 27, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6246/text.

[48]Brainard, Keith and Zorn, Paul. “The 80-percent Threshold: Its Source as a Healthy or Minimum Funding Level for Public Pension Plans,” National Association of State Retirement Administrators, January 2012. https://www.nasra.org/files/Topical%20Reports/Funding%20Policies/80_percent_funding_threshold.pdf.

[49]Comtois, James. “Average Funding Ratios of Most Public Plans Far More Divided than Previously Believed – Report,” Pensions & Investments, October 23, 2018. https://www.pionline.com/article/20181023/ONLINE/181029950/average-funding-ratios-of-most-public-plans-far-more-divided-than-previously-believed-8211-report.

[50]Caribbean Business. “Puerto Rico Designated an Opportunity Zone under US Tax Reform,” April 9, 2018. https://caribbeanbusiness.com/puerto-rico-designated-an-opportunity-zone-under-us-tax-reform/.

[51]Ellis, Ryan and Conda, Cesar. “Opportunity sprouts in impoverished areas, thanks to tax reform,” Washington Examiner, May 3, 2018. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/opportunity-sprouts-in-impoverished-areas-thanks-to-tax-reform.

[52]Hoke, William. “Puerto Rico Governor Says No CFC Tax Increase in Tax Reform Bill,” Tax Notes, October 11, 2018. https://www.taxnotes.com/editors-pick/puerto-rico-governor-says-no-cfc-tax-increase-tax-reform-bill.

[53]Sepp, Pete. “An Open Letter to the House Ways & Means Committee: Here’s How Tax Reform Can Deliver for Puerto Rico!” National Taxpayers Union, November 7, 2017. https://www.ntu.org/library/doclib/L17-11-06-Puerto-Rico-Territories-Tax-Transition.pdf.

[54]Ellis, Ryan. “Trump Can Radically Reform Taxes For Small Business And Families Without Congress,” Forbes, April 28, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanellis/2017/04/28/trump-can-radically-reform-taxes-for-small-business-and-families-without-congress/#4c5936075507.

[55]Grabow, Colin. “No Jones Act Cost to Puerto Rico? I Have My Doubts,” Cato Institute, August 8, 2018. https://www.cato.org/blog/dont-believe-amp.

[56]Grabow, Colin. “Puerto Rico, LNG, and the Jones Act,” Cato Institute, February 8, 2019. https://www.cato.org/blog/puerto-rico-lng-jones-act.

[57]Government Accountability Office. Puerto Rico: Characteristics of the Island’s Maritime Trade and Potential Effects of Modifying the Jones Act, March 14, 2013. https://www.gao.gov/assets/660/653046.pdf.

[58]Congressional Budget Office. The Effects of a Minimum-Wage Increase on Employment and Family Income, February 2014. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/44995-MinimumWage_OneColumn.pdf.

[59]Kupiec, Paul and Nabil, Ryan. “Minimum-Wage Activists Should Look to Puerto Rico for Clues to the Future,” National Review, April 13, 2016. https://www.nationalreview.com/2016/04/minimum-wage-california-new-york-puerto-rico-future/.

[60]Sepp, Pete. “Legislative Memorandum: Puerto Rico’s Finances,” National Taxpayers Union, October 9, 2015. https://www.ntu.org/publications/detail/legislative-memorandum-puerto-ricos-finances.

[61]Reagan, Ronald. “Puerto Rico and Statehood,” The Wall Street Journal, February 11, 1980.

[62]Congressional Task Force on Economic Growth in Puerto Rico,Report to the House and Senate: 114th Congress, December 20, 2016. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Bipartisan%20Congressional%20Task%20Force%20on%20Economic%20Growth%20in%20Puerto%20Rico%20Releases%20Final%20Report.pdf.

[63]Sepp, Pete and Trujillo, Max. “Getting Puerto Rico Out of the Austerity Trap,” Morning Consult, February 20, 2019. https://morningconsult.com/opinions/getting-puerto-rico-out-austerity-trap/.