(pdf)

This past June, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report estimating the potential financial benefits of implementing its thousands of open recommendations across 10 government entities. The report concluded that if the agencies followed through and implemented all of GAO's open recommendations, this could produce measurable savings in the range of $92 billion to $182 billion.

Among GAO’s recommendations, one particular unimplemented reform stands out because it highlights inefficiencies and waste in Medicare. Higher rates are provided for services at hospital outpatient care facilities than for similar services provided by physicians. If there are opportunities to save taxpayer dollars in Medicare – one of the fastest growing federal programs and a source of long-term budget liabilities – lawmakers and the directors of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) should pay attention. In 2020, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that this could save taxpayer funds in the range of $39 billion to $141 billion over ten years (details below).

The Rise of Hospital Outpatient Departments

The open Medicare recommendation originates from a 2015 GAO report on the rise in outpatient care and the rise in costs for services at hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) as compared to those provided in a physician’s office

GAO notes that since the late 1970s, the number of HOPDs has greatly increased as hospitals began either acquiring physician practices, or hiring physicians to work as salaried employees, a phenomenon GAO calls “vertical consolidation.” By 1981, 41 percent of hospitals had HOPDs and only six years later, in 1987, that number had grown to 69 percent.

The growth in HOPDs has not slowed. According to GAO’s 2015 report, the number of vertically consolidated hospitals and physicians nearly doubled going from 96,000 to 182,000 from 2007 to 2013.

Why Are HOPDs and Costs Growing So Rapidly?

Two main factors contribute to the rise in HOPDs and the more recent decline in individual practices. The first is driven by hospitals' push for increased bargaining power vis-à-vis insurers. When hospitals vertically consolidate, they have increased leverage over insurers to bargain for higher prices for the services they provide to patients.

The second factor, and of more concern, is Medicare’s incentive structure. Although hospitals cannot bargain with Medicare for higher prices, they don’t need to because Medicare already pays a higher rate to hospitals if care is rendered in an HOPD.

As a recent health services study notes, this occurs due to Medicare payments being tied to fee schedules, and the fee schedules are tied to the site of care. Care provided by an individual physician is tied to the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). On the other hand, care provided in a hospital-based facility is billed through the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS).

When billing is done through the PFS, one payment is released, and this payment is based on the physician's work effort and office expenses. However, when billing goes through the OPPS, there are two payments: one payment for office expenses, and a second payment that covers facility services.

This creates a payment disparity because payments through OPPS generally exceed payments to individual physicians. On average, individual physicians would have earned 80 percent more had they billed through OPPS rather than the physician fee schedule. The health services study went on to calculate the disparity and found that, “Medicare reimbursement for physician services would have been $114,000 higher per physician, per year, if a physician were integrated compared to being non-integrated.”

Further data, published by the Medicare Payment Advisory Clinic analyzing the period between 2012 to 2018, shows physicians saw a 2 percent decrease in billing for office visits, whereas hospital clinics saw a 37 percent hike.

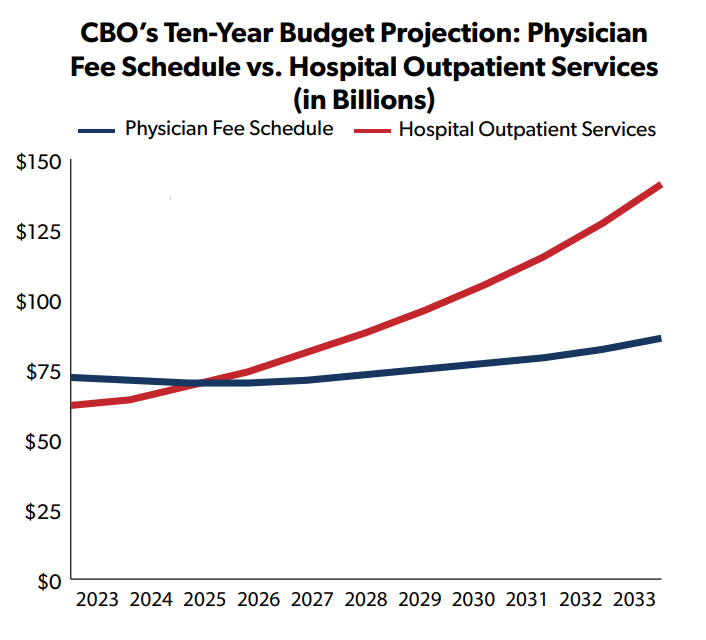

CBO’s most recent budget baseline estimates that in FY 2023, Medicare will spend $72 billion through the PFS program and $62 billion for hospital outpatient services. However, over the next decade PFS is projected to grow by 2 percent annually while the outpatient program will increase by 9 percent.

The current payment structure with different rates at different locations for the same services creates incentives for both physicians and hospitals to shift to outpatient care. Hospital-based billing increases total payments, and these payments are disbursed at the discretion of the hospital. In other words, when physicians and hospitals consolidate, everyone makes more money. This creates a large incentive for hospitals to buy, and physicians to sell, physician practices.

Medicare Payment Schedules Should Be Equalized

Providers are able to charge a higher rate even when the same service is being performed and transfer that rate increase onto the taxpayers’ tab. In 2012, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recommended site-neutrality in determining payment rates. The report noted:

In 2011, Medicare paid about 80 percent more for a 15-minute office visit in an [H]OPD than in a freestanding physician office. The Commission maintains that Medicare should seek to pay similar amounts for similar services, taking into account differences in the definitions of services and differences in patient severity. Setting the payment rate equal to the rate in the more efficient sector would save money for the Medicare program, lower cost sharing for beneficiaries, and reduce the incentive to provide services in the higher paid sector.

In 2015, GAO agreed that Congress should direct the Secretary of Health and Human Services to equalize payment rates between physician office visits and visits to an HOPD. GAO recommended the OPPS and PFS rates be equalized because on average, Medicare paid an additional $51 when the same service was performed in an HOPD as opposed to a physician’s office.

The recommendation was partially addressed in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015. This law gave CMS some authority to address the discrepancy in rates charged through HOPDs versus PFS, however its reach was limited to newer HOPD facilities, existing facilities were grandfathered in with the previous rate structure. This was estimated to save $9.3 billion over 10 years.

With broader implementation, the savings could be much greater. Then-President Trump’s FY 2021 budget proposed two related reforms. The first would equalize the payment rates regardless of when the facility was established. CBO estimated that this would reduce outlays by $39 billion over ten years. The second would equalize payment rates for certain services to include imaging tests, clinic visits, and drug administration. CBO estimated this would save $102 billion over the decade.

Several bills have been introduced in the House and Senate that would implement these reforms.

H.R.2863, the Preventing Hospital Overbilling of Medicare Act introduced by Representative Victoria Spartz (R-IN) would eliminate the grandfathering provision.

H.R. 3561, the Promoting Access to Treatments and Increasing Extremely Needed Transparency (PATIENT) Act, introduced by Reps. Cathy McMorris Rogers (R-WA) and Frank Pallone (D-NJ) includes a provision to implement site-neutral policies only for prescription drugs administered under Part B of Medicare in off-campus HOPD for a savings of $3.8 billion over ten years, according to CBO. The bill includes many other provisions and in total would increase spending by $11.4 billion over the first five years. With other spending reforms in the later years of the budget window reduce the net ten-year cost $3.2 billion. It would also increase revenues by $3.5 billion over the decade.

H.R. 4473, the Medicare Patient Access to Cancer Treatment Act, introduced by Rep. Jodey Arrington (R-TX) would provide for site neutral payment for cancer care services starting in 2025. A savings estimate is currently unavailable.

H.R. 4822, the Health Care Price Transparency Act of 2023, introduced by House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Jason Smith (R-MO), would phase-in site-neutrality over four years. The bill, which also includes additional provisions related to billing and pricing transparency, was passed by the Committee on Jul 26, 2023. A CBO cost estimate is not yet available.

S. 1869, the Site-based Invoicing and Transparency Enhancement Act, introduced by Senators Mike Braun (R-IN), Maggie Hassan (D-NH), and John Kennedy (R-LA), would eliminate the grandfathering provision, implement transparency for outpatient billing practices, and “prevent off-campus emergency departments from charging higher rates than on-campus emergency departments when standalone emergency facilities are located in close proximity to a hospital.” $100 million of the savings in the package would be used to fund a new nurse training program.

Conclusion

The current Medicare incentive structure costs taxpayers billions and, according to some observers, can lead to a lower quality of care. It is imperative that lawmakers work with federal agencies to dismantle this incentive structure carefully, and delicately to disrupt further unnecessary spending and protect American taxpayers from fraud, waste, and abuse.