(pdf)

Full expensing of capital expenditures was one of the most important elements of the tax reform law, the “killer app” of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Preserving it should be a priority, not an afterthought to be consigned to the uncertain and temporary fate of other tax extenders.

Expensing vs. Asset Depreciation

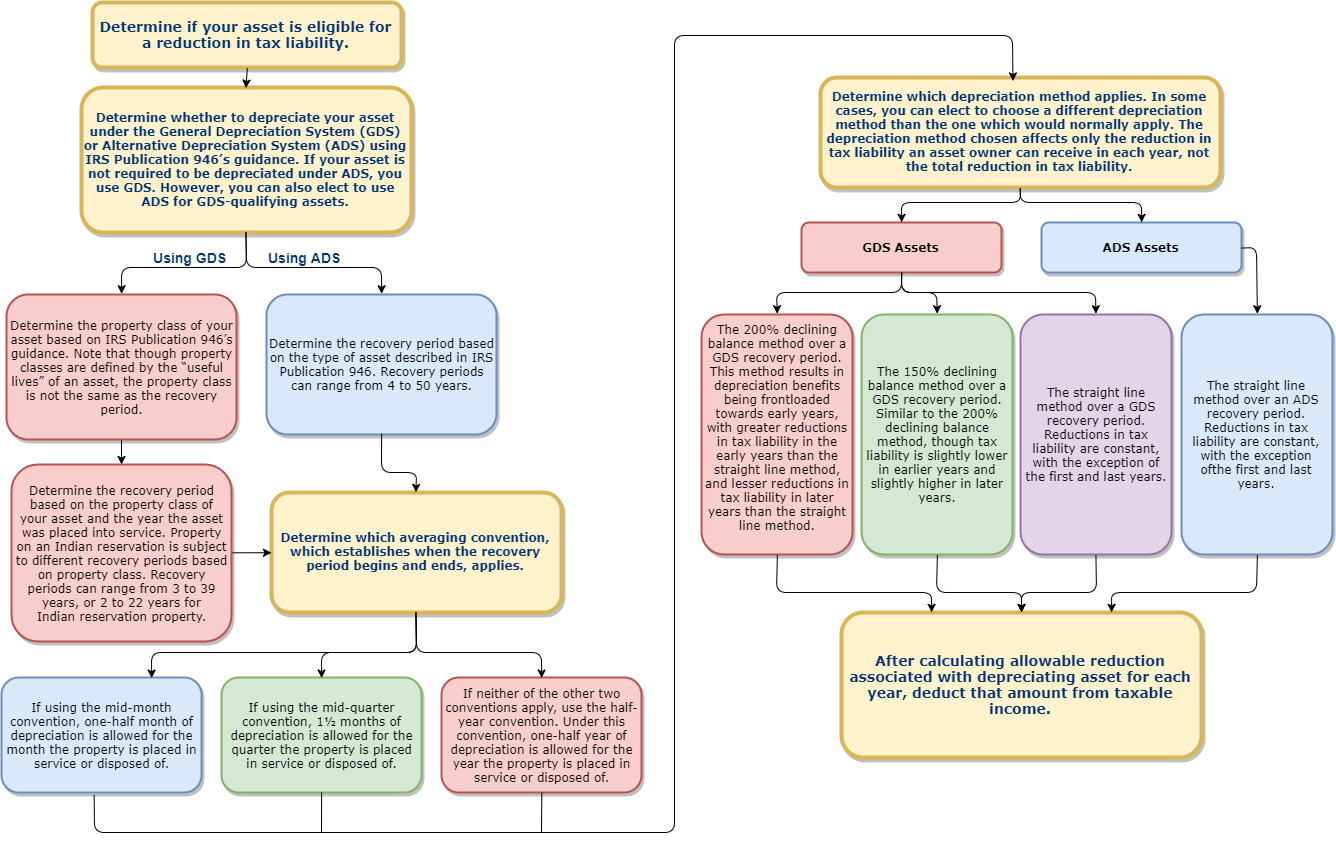

Our tax code enables businesses to deduct the cost of capital investments from their tax liability as they calculate their taxable income. Prior to the passage of the TCJA, businesses making capital investments were forced to navigate complicated asset depreciation schedules. The new tax law, however, had a full expensing provision that enabled them to do so fully and immediately in the year they made the investment.

That’s important for two main reasons. First, asset depreciation is complicated, as NTUF’s paper on the subject demonstrated:

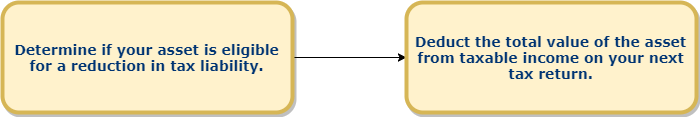

Full expensing is not.

Compliance with the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) for asset depreciation used to cost businesses approximately $23 billion, or 448 million hours, a year — a deadweight loss. Full expensing saves businesses from wasting time complying with a needlessly complicated system.

But the real benefit of full expensing comes from the effect it has on the incentive to invest. Businesses prefer cash in hand to a promised tax incentive somewhere down the line, and for good reason. Cash in hand can be reinvested immediately for more productive uses, while cash owed up to 50 years later of course cannot. Capital investments in turn lead eventually to improved productivity — and with that, higher wages.

Cash on hand also faces no “inflation tax.” One analysis of the effects of this found that businesses recovering asset value through the MACRS system received only between 95.6 percent (over a 3-year recovery period) and 37.7 percent (over a 50-year recovery period) of the value they would have recovered under full expensing.

Budget Idiosyncrasies

Despite these obvious benefits, full expensing appears to “cost” Uncle Sam revenue compared to asset depreciation because of the quirks of budget scorekeeping. Legislative proposals are scored based on ten-year budget windows, which makes full expensing appear to have a high cost.

Whether under a full expensing or asset depreciation regime, businesses receive the same absolute value of their tax break eventually. But asset depreciation can be stretched out over periods of time reaching up to 50 years — the last 40 years of which do not show up under a normal budget window for a budget scorekeeper.

As such, any revenue loss or gain that takes place outside the ten-year budget window effectively does not exist for budgetary purposes. Because expensing “books” as many as 50 years of revenue reduction in the course of a single year and the economic growth effects take place over a longer timeframe, it appears to be artificially “expensive” in terms of revenue reduction over the ten-year window.

Despite ultimately costing the federal government next to nothing, full expensing found itself a casualty of budget reconciliation rules because of this fact. Full expensing was put in place for the first five years of the tax reform law, but will be phased out to minimize its “cost” when dealing with the complicated math of legislating to a target score. The Joint Committee on Taxation score of the TCJA has full expensing “costing” $119.4 billion over the five years it is in place, but actually “saving” $33 billion over the course of the five-year phase-out.

A New Extender?

These budget quirks may be what makes full expensing so politically difficult, but they are also what could make it an attractive candidate to become another tax extender.

Tax extenders are tax breaks that are statutorily set to expire after a year or two, but are almost always extended. This is bad policy, as businesses that benefit from tax breaks in the extenders package receive no certainty that these breaks will indeed be extended until the last moment — and sometimes not even then. Congress has occasionally allowed tax extenders to expire, then retroactively put them back in place.

However, tax extenders offer one major benefit to legislators: the ability to manipulate a very credulous budget scorekeeping system. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) may score a tax break that reduces revenue by $1 billion per year as “costing” $10 billion over ten years. Yet if that same tax break is statutorily set to be in place only for one year, the CBO must score it as costing only $1 billion over ten years — even if everyone knows it will be “extended” each year for the next ten years.

Therefore, it makes some political sense that full expensing could become another extender to mask the “score” it receives. It’s hard to overstate how ludicrous this state of affairs is. To sum up:

Full expensing effectively costs the federal government nothing relative to the alternative of asset depreciation, and provides superior incentives while reducing compliance costs.

Because of the ten-year budget window, it artificially appears to reduce revenue by a significant amount when scored.

Therefore, Congress may avoid this problem by using a shady budget maneuver to show only one year of this “cost” at a time.

The obvious solution here is to fix the budget scorekeeping methods that allow silliness like this to persist in the first place. That’s why NTUF launched the Taxpayer’s Budget Office to try to hold budget scorekeepers (and the Congress that establishes the rules they are forced to operate under) accountable when they fail to accurately represent the effects that legislation would have on taxpayers.

But in the meantime, Congress should resist the urge to fight fire with fire. Full expensing is too important to toss into the annual tax extenders circus.

Imagine a case in which a provision as economically impactful as full expensing was considered year to year based on the whims of Congress. Businesses seeking to make productive investments may put them off indefinitely until Congress got around to “extending” full expensing. After all, doing so could mean the difference between a 50-year, compliance-heavy recovery period and a simple one-year recovery period.

Or worse, businesses could be forced to make guesses on whether Congress would extend full expensing that year, or retroactively to investments made under a depreciation year. All along, companies would be incentivized to spend inordinate amounts of money lobbying Congress each year to achieve the desired result.

Conclusion

Whatever the politics and the optics, making full expensing permanent is the right policy. It’s a clear-cut way to encourage investment and reduce compliance burdens on businesses. It’s worth spending some political capital to permanently establish a smart tax policy like full expensing.