(pdf)

July 15, the delayed date when taxpayers in most states are liable to file and pay state and federal taxes, has come and gone. Given the ongoing pandemic and recession that Americans are facing, it’s likely that tens of thousands more taxpayers will risk falling afoul of privacy-violating “tax delinquent lists” that some states make public.

Given the unique challenges that taxpayers are facing this filing season, NTU spearheaded a group of over 50 organizations,[1] many of them state-based, advocating for Treasury Secretary Mnunchin to push back the payment deadline into 2021. Unfortunately, the Secretary failed to act, and taxpayers in nearly all states are expected to have filed and paid taxes, pandemic notwithstanding.

For most who fail to file or pay on time, this means the usual (and stressful enough) process of dealing with scary revenue agency letters and trying to find the money to clear one’s tax debt. For an unfortunate few, however, it can mean having one’s privacy violated by state departments that try to enlist the help of public shaming to get tax delinquents to cover their outstanding balances.

That’s because for taxpayers in certain states, outstanding tax debt can merit inclusion in publicly available lists of “tax delinquents,” or taxpayers who have failed to square their debts with state revenue officials. These lists often include a great deal of private tax information in an attempt to utilize public shame to collect unpaid tax debts.

The Practice of Publishing Tax Delinquents Lists

Americans fail to pay taxes on time for many reasons, very few of which are best addressed by the publication of private information such as delinquent taxpayers’ names, addresses, and amounts owed. The economic pain that many Americans are facing at this moment drives home the inadvisability of this method of tax collection, but it nonetheless represents a violation of taxpayer rights even in the best of economic circumstances.

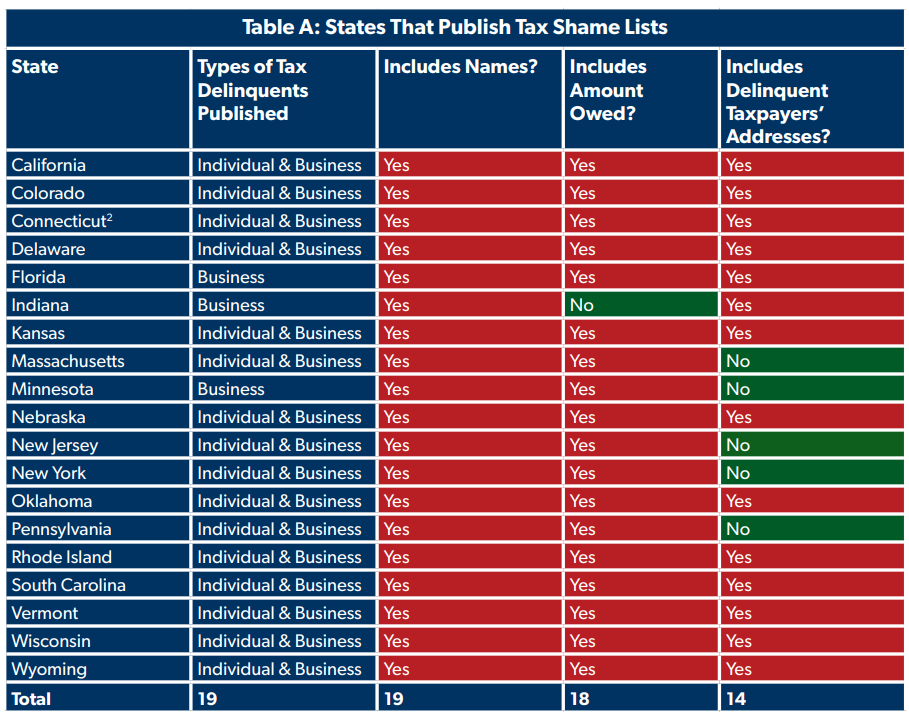

The practice is unfortunately fairly widespread across the country. Table A lists the states that make these sorts of lists publicly available, and the extent of the information that they provide. All of the 19 states that publish tax shame lists publicize the names of the individuals (or the names of the owners of the businesses) failing to pay off their tax liabilities. All but one of these states include the amount owed, and all but four display the address of the offending non-taxpayer. Many more localities also publish tax delinquents lists, even in states where the state government does not.

And “shame lists” they are. Advocates of publicly-available tax delinquents lists could, in theory, also attempt to justify their existence in the name of public knowledge. However, the authors of these arguments undermine this justification with their own words.

News releases by revenue departments publicizing these lists routinely tout the revenue recovered from delinquent taxpayers on these lists (while declining, of course, to consider that repayment may have occurred as a result of the myriad of other tools governments use to collect unpaid taxes).[3] Louisiana, one of the first states to experiment with online shame lists, gave away the game by calling its since-discontinued program “CyberShame,”[4] and Colorado named its program the “Hall of Shame.”[5]

So given that the purpose of tax delinquents lists is to shame delinquent taxpayers into paying up, it’s worth asking how exactly tax justice is expected to take place. When publicly posting the names, addresses, and financial information of Americans, it’s naive to assume consequences to be limited to tax delinquents not being invited to the neighborhood cookout.

In other words, public-shaming governments can’t have it both ways. On the one hand, if they expect tax delinquents lists to have serious consequences that will pressure Americans behind on their taxes to pay up, that represents a draconian and deeply irresponsible means of attempting to collect unpaid tax revenue. Such actions would represent an abrogation of a government’s duty to protect its citizens, regardless of the status of their tax bill.

On the other hand, if the consequences of tax delinquents lists are minimal, then they represent an also irresponsible publication of private information for little purpose. Tax shame lists can’t be simultaneously harmless and effective.

And the publication of private American citizens’ personal information in this fashion can have consequences unrelated to tax repayment. Scams where individuals impersonate Internal Revenue Service (IRS) agents to try to leech funds from taxpayers are such a concern that the IRS dedicates significant effort trying to foil them.[6] Publishing private information such as names, addresses, and even amounts owed makes it painfully easy for a would-be scammer to convincingly impersonate a state revenue official attempting to collect unpaid debts.

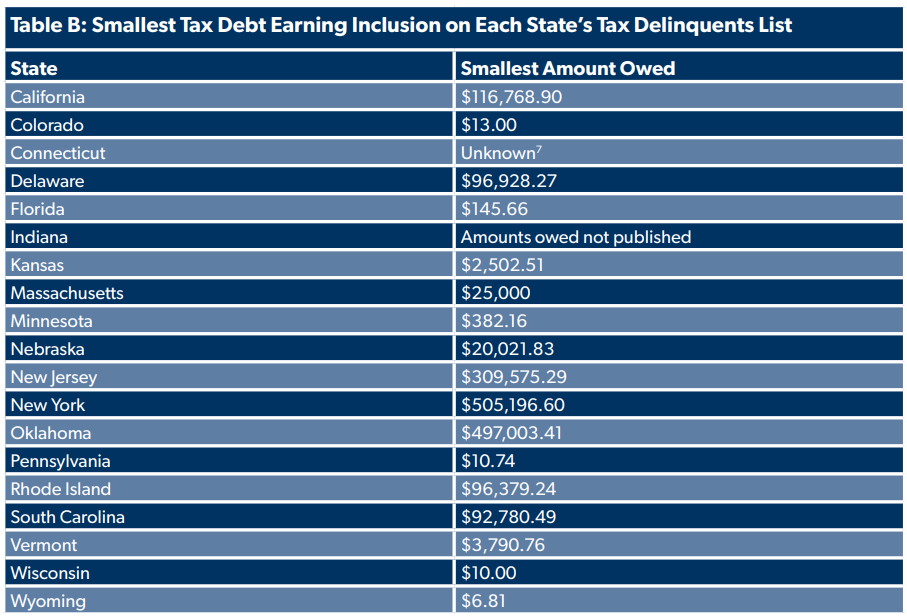

Defenders of tax shame lists could also argue that most tax delinquents lists target wealthy scofflaws, not everyday Americans behind on their taxes. While this is true for some states, many others publish almost amusingly low debts. Table B lists the smallest amount owed on the tax delinquents lists of each state described in Table A.

As Table B shows, the argument that listing only the wealthiest Americans intentionally shirking their duty to pay taxes could potentially be made convincingly in states like New York or Oklahoma. In states like Colorado, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Wyoming, on the other hand, where the smallest debts shown amount to loose change, this argument is laughable.

Neither can tax debts in the tens of thousands of dollars necessarily be dismissed as the intentional tax-avoidance of fat cat scofflaws. Debt can easily pile up on Americans down on their luck, and shaming them is rarely the solution. Even in cases where taxpayers do accrue large unpaid debts, that does not disqualify them from their basic right to privacy and confidentiality.

It’s also not necessarily the case that those included on tax delinquents lists are aware that they owe any tax. Nearly all states require that taxpayers be mailed a notice of unpaid debts, but the exact process can vary by state. States such as Nebraska require that a delinquent taxpayer be sent multiple notices, have a tax lien filed against them, and have all appeal rights exhausted before they merit inclusion on a list.[8] California, on the other hand, mails a single letter 30 days before a taxpayer can appear on its list.

It’s not hard to imagine taxpayers missing a single letter — particularly now, when many Americans have left their primary residence to avoid COVID-19 hotspots or to take care of family members. When the Hartford Business Journal ran an exposé of state legislators on the state’s tax delinquents list, three reported being unaware of their tax debts, all below $2,000.[9]

As states have continued to publicize taxpayers’ private information, the federal government has endeavored to pass legislation protecting the confidentiality of tax returns. Multiple bills at the federal level, including Taxpayer Bill of Rights 2,[10] the IRS Restructuring and Reform Act,[11] and the recently-passed Taxpayer First Act have all become federal law in the last few decades.[12]

Of course, none of this is to dismiss the responsibility of Americans to pay their tax bills and the seriousness of failing to do so. Nevertheless, taxpayers’ privacy rights do not disappear as a result of an unpaid bill. After all, states have plenty of other less invasive and more effective means of collecting tax debts — methods the 32 states that do not publish tax delinquents lists manage to use to collect unpaid taxes without resorting to public shaming.

Are Shame Lists Even Effective?

Academic research on the issue of tax shame lists suggests that, even setting privacy concerns aside, they often fail to achieve their intended purpose of retrieving unpaid tax debts. One analysis from the German University of Hohenheim found that tax shame lists can deliver some marginal increases to revenue collections in the short term, but that the effect quickly drops off.[13]

One reason for the drop-off is that the reputational damage that comes to corporations and pass-through businesses appearing on a tax delinquents list can cause significant economic harm. Causing businesses to lose out on investment and contract opportunities has an economic cost — particularly in states that are less discerning about ensuring that appeal rights are exhausted and a lien has been filed before including a delinquent taxpayer on a public shame list.

Recent history can prove instructive as to how businesses with every intention of following tax law and remitting their obligations can easily end up blacklisted. In 2018, the Supreme Court overturned longstanding precedent regarding the conditions under which remote businesses could be held responsible for collecting and remitting sales tax payments.

Almost overnight, some remote businesses saw the number of states they were expected to remit sales tax to multiply significantly. Many were completely unaware of this new responsibility, with 29 percent of small business owners reporting that they had not even heard of the change.[14] Of those that were aware, many were unprepared to implement the changes necessary to comply. Shortly after the ruling, Thomson Reuters put the number of midsized firms with the infrastructure to comply with their new tax compliance obligations at a staggeringly low 8 percent.[15]

Unfortunately, tax delinquents lists often blacklist such businesses along with the intentional scofflaws. Doing so can unnecessarily harm businesses that have failed to meet tax obligations for non-malicious reasons — and in so doing, the broader economy as well.

There are also behavioral reasons to think that tax delinquents lists may not achieve the intended results. Former Internal Revenue Service Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson noted that not only may tax delinquents list backfire among citizens with an individualistic and anti-tax worldview, but they can also “indicate to those who are compliant that the norm is not followed by many people.”[16] In other words, taxpayers viewing delinquents lists may be less inclined to shame their non-paying neighbors, and more inclined to think that not paying taxes is more widespread than they had thought (and therefore, a more valid option).

Aren’t Tax Liens Public Already?

Governments issuing public tax delinquents lists sometimes argue that a tax lien has been filed,[17] making the unpaid debt a matter of public record.[18] This is true in the most basic sense, but it misses significant differences in the accessibility of, and purpose behind, tax delinquents lists and tax liens records.

Though tax liens are public legal documents, accessing them requires a great deal more effort than clicking on a link on a state Department of Revenue page. Most records of tax liens, to the extent they are available online, require a significant payment to access, and would be difficult for a layperson to run across. Many require having a person’s specific information to search. As such, tax lien databases are highly unlikely to be useful for the purposes of creating a broad-based tax delinquent public shaming effort.

State-published tax delinquents lists, on the other hand, are often available on states’ revenue department homepages. Taxpayers currently paying their taxes, and most likely to be in an unforgiving mood towards those not doing so, could run across large, comprehensive lists easily, without needing any personal information to search.

There’s also the matter of the reasoning behind the public nature of tax liens records versus tax delinquents lists. Tax liens records are accessible (by a determined enough individual) largely for use by creditors and credit reporting agencies for the purposes of establishing the financial trustworthiness of a potential loanee. Indeed, the easiest way to access information about currently active tax liens against an individual is to view that individual’s credit report.

In contrast, tax delinquents lists serve no such purpose, and states make little effort to disguise the fact that their sole utility is to invite public shame and punish delinquent taxpayers.

Reform Options

Most of the states with tax delinquents lists have some form of Taxpayer Bill of Rights enacted into law through the legislative process.[19] Some of these Bills of Rights even reference a right to taxpayer privacy, a right that is fairly clearly being violated through the existence of tax delinquents lists.

State legislatures seeking to curb their states’ usage of tax delinquents lists should focus on amending these Taxpayer Bills of Rights to clarify that public shaming for the purposes of collecting unpaid tax bills is an unacceptable reason to violate taxpayer privacy. Publication of private taxpayer information should face a significantly higher bar before it is considered justified.

News media outlets should also recognize their responsibility to stop publicizing tax delinquents lists. It’s fairly safe to say that the average American spends little time trawling through state department of revenue news releases, but news outlets frequently spread these lists by writing articles about them.

Yet they should resist this impulse. As Ninth Circuit judge Charles Merrill wrote in his decision in Virgil v. Time, privacy violations for “newsworthy” topics cease to be justified when “the publicity ceases to be the giving of information to which the public is entitled, and becomes a morbid and sensational prying into private lives for its own sake, with which a reasonable member of the public, with decent standards, would say that he had no concern."[20]

Conclusion

There’s some reason for optimism that tax delinquents lists may eventually die out, as at least three states — Illinois, Maryland, and New Jersey — have discontinued or stopped updating their lists since last year. But eighteen is still far too many.

Taxpayers should be able to expect that generally, private information will remain between themselves, the tax officials reviewing their cases, and potentially the legal system should they fail to pay their tax bills.

The coronavirus and the economic pain it has led to provide an extra incentive to stop punishing delinquent taxpayers through violations of their privacy. But there is ample enough reason in the best of times to expect state revenue departments to be more discerning with who they provide personal information to.

[1] National Taxpayers Union. (2020). “Letter to: Sec. Steven Mnunchin (United States Secretary of the Treasury).” June 29, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.ntu.org/library/doclib/2020/06/Tax-Day-Delay-Endorsement-letter.pdf

[2] Connecticut does not publish its list of delinquent taxpayers online. However, it is available to be picked up in person at the state’s Department of Revenue office, and portions of the list have been publicized by news outlets.

[3] State of California Franchise Tax Board. “Top 500 Delinquents Taxpayers list.” May, 2018. https://www.ftb.ca.gov/about-ftb/newsroom/tax-news/may-2018/top-500-delinquents-taxpayers-list.html

[4] Louisiana Department of Revenue. “Names of Delinquent Taxpayers.” January 17, 2001. https://revenue.louisiana.gov/NewsAndPublications/NewsReleaseDetails/55

[5] Crummy, Karen. “Worst tax evaders owe $63 million.” Denver Post. April 14, 2008. https://www.denverpost.com/2008/04/14/worst-tax-evaders-owe-63-million/

[6] Internal Revenue Service. “Tax Scams/Consumer Alerts.” May 22, 2020. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/tax-scams-consumer-alerts

[7] Because Connecticut’s list must be accessed in-person in Hartford, NTUF did not view the list itself, but merely confirmed its existence.

[8] Nebraska Department of Revenue. “Nebraska Delinquent Taxpayer List.” July 20, 2020. https://revenue.nebraska.gov/about/nebraska-delinquent-taxpayer-list

[9] Bordonaro, Greg and Pilon, Matt. “CT state lawmakers among delinquent taxpayers.” February 10, 2020. https://www.hartfordbusiness.com/article/ct-state-lawmakers-among-delinquent-taxpayers

[10] Public Law 104-168, Taxpayer Bill of Rights 2, July 30, 1996. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-104publ168/html/PLAW-104publ168.htm

[11] Public Law 105-206, Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998, July 22, 1998. https://www.congress.gov/bill/105th-congress/house-bill/2676

[12] Public Law 116-25, Taxpayer First Act, July 1, 2019. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3151

[13] Dwenger, Nadja and Treber, Lukas. “Shaming for Tax Enforcement: Evidence from a New Policy.” Hohenheim Discussion Papers in Business, Economics and Social Sciences, August 4, 2018. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/182441/1/1031664017.pdf

[14] Puri, Ritika. “What the Wayfair Decision Means for American E-commerce.” Performance Magazine, April 9, 2019. https://www.performancemagazine.org/wayfair-decision-american-ecommerce/

[15] Paladino, Alex. “Tax day of reckoning comes for e-commerce companies.” Thomson Reuters, August 15, 2018. https://blogs.thomsonreuters.com/answerson/tax-day-of-reckoning-comes-for-e-commerce-companies/

[16] Olson, Nina. “National Taxpayer Advocate 2007 Report to Congress, Volume Two.” Taxpayer Advocate Service, 2007. https://www.irs.gov/pub/tas/arc_2007_vol_2.pdf

[17] South Carolina Department of Revenue. “South Carolina's Top Delinquent Taxpayers.” Retrieved from: https://dor.sc.gov/top250 (Accessed July 20, 2020.)

[18] This is not always a prerequisite for ending up on a tax delinquents list, in any case. States such as Delaware, Nebraska, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina affirmatively state that a tax lien or warrant must be filed before a delinquent taxpayer ends up on one such list, but most others only require attempted notice a certain period beforehand.

[19] Note that Taxpayer Bills of Rights discussed in this section are different from Colorado’s TABOR, which pegs the limit for growth in state tax revenues to that induced by inflation and population growth. Taxpayer Bills of Rights discussed in this section refer to enumerated lists of taxpayer rights during the taxpaying process.

[20] Virgil v. Time, Inc., 527 F.2d 1122 (9th Cir. 1975) https://casetext.com/case/virgil-v-time-inc