Key Facts

- The One Big Beautiful Bill Act permanently increased the Child Tax Credit and indexed it to inflation, delivering the most significant improvement to the credit since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

- The Child Tax Credit directly targets families and provides households with greater budgetary flexibility to address the challenges they are most affected by, from the cost of food to increasing utility bills or emergency medical expenses.

- Enhancing the Child Tax Credit could be an important part of Republicans’ affordability agenda moving forward, bringing broad-based financial relief to American families through a popular part of the tax code.

Introduction

Members of Congress are looking to 2026 as a critical time to secure legislative wins prior to the midterm elections, which will shape the rest of President Trump’s final term in office. With a unified government, Republicans can use the budget reconciliation process to pass major tax and spending legislation, as they recently did with the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA).

Affordability is quickly becoming the top concern for both voters and lawmakers and will likely be a key element of any upcoming reconciliation measures. Consumer confidence is declining as expectations worsen for business conditions, the labor market, and income. Legislators are also grappling with policy questions related to the cost of health care, housing, and energy.

Enhancing the Child Tax Credit could be an important part of Republicans’ affordability agenda prior to the midterms, bringing broad-based financial relief to American families through a popular part of the tax code. OBBBA permanently increased the base per-child amount of the Child Tax Credit starting in 2025 and indexed it for inflation starting in 2026. These changes bring long-overdue certainty for families by preventing a sudden drop in the credit amount scheduled for 2026 and ensuring that the value of the credit keeps pace with the rising cost of living. Yet, the version of the bill that became law included a more modest increase in the credit than earlier versions, leaving room for agreement on further changes.

The Child Tax Credit directly targets families and provides households with greater budgetary flexibility to address the challenges they are most affected by, from the cost of food to increasing utility bills or emergency medical expenses. Furthermore, the Child Tax Credit is a simple way to address affordability in comparison to benefits that rely heavily on government-run programs and have unpredictable or unclear costs.

Crafting a Child Tax Credit that is resilient to change in economic conditions, reliable for taxpayers, and effectively targeted toward those who need it the most would be a welcome addition to the affordability agenda for 2026.

Background

Prior to the introduction of the Child Tax Credit, the tax code assisted families through the dependent exemption, which reduced taxpayers’ taxable income on a per child basis. By the 1990s, the real value of the exemption had eroded significantly since its creation in 1948. There were also concerns about the exemption providing greater benefit to higher income families and no benefit to lower income families without a tax liability.

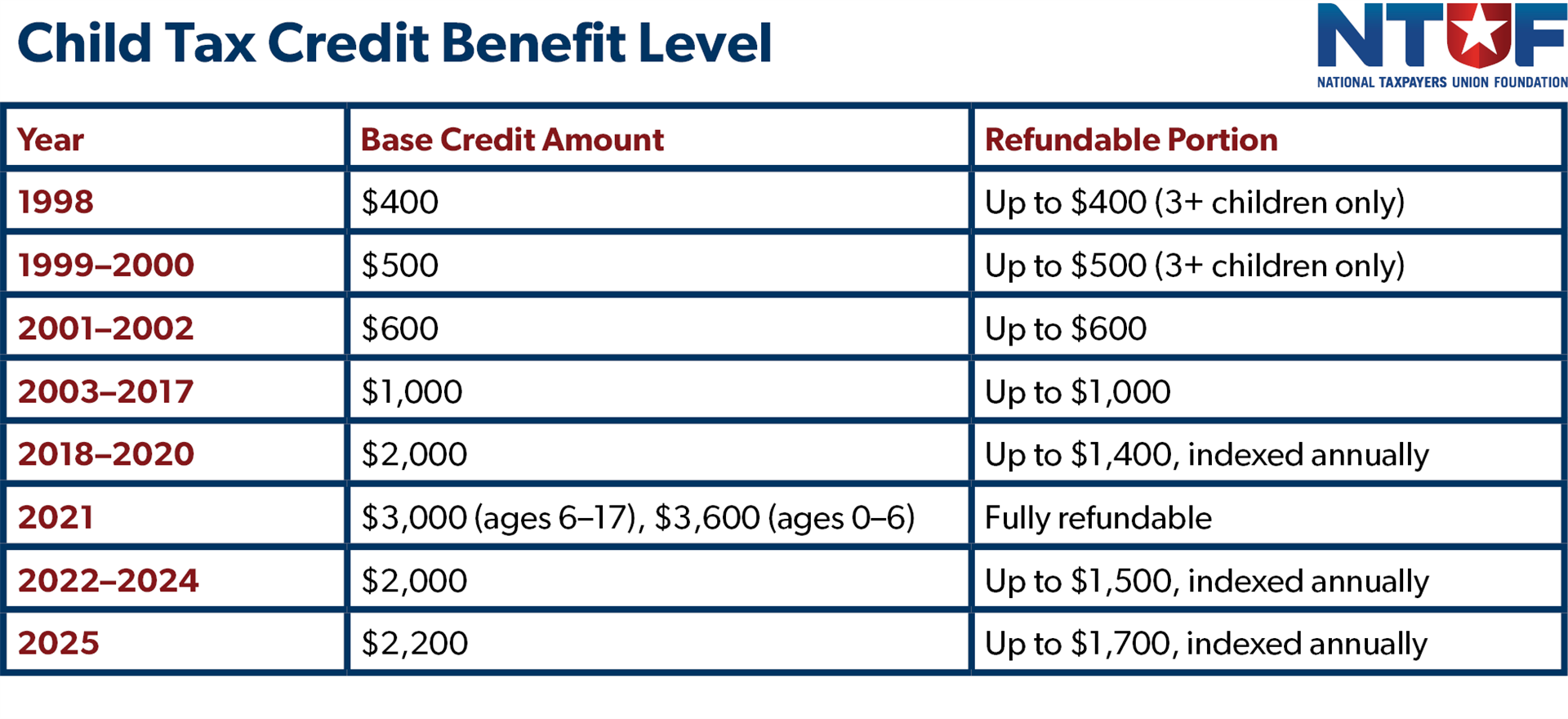

As a result, the Child Tax Credit was conceptualized as early as 1991 through a bipartisan commission and was made law by the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997. It began as a $400 credit for allowable dependents in 1998 and was scheduled to increase to $500 the following year. Credit refundability allowed for those with three or more dependents, unlike the refundability calculation today, which is determined by income level. However, due to the formula used, alongside the reduced tax liability of the lowest-income earners as a result of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the most impoverished families generally did not qualify for a refundable credit.

The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (EGTRRA) of 2001 increased the amount of the credit to $600 and broadened refundability. EGTRRA replaced the family size based formula for refundability with a new formula for taxpayers with earned income above $10,000, and adjusted that threshold for inflation. While the Child Tax Credit was due to incrementally increase until it reached $1,000, subsequent laws increased the amount to $1,000 by 2004. Laws passed during the Obama era reduced the refundable portion’s earnings threshold to $3,000.

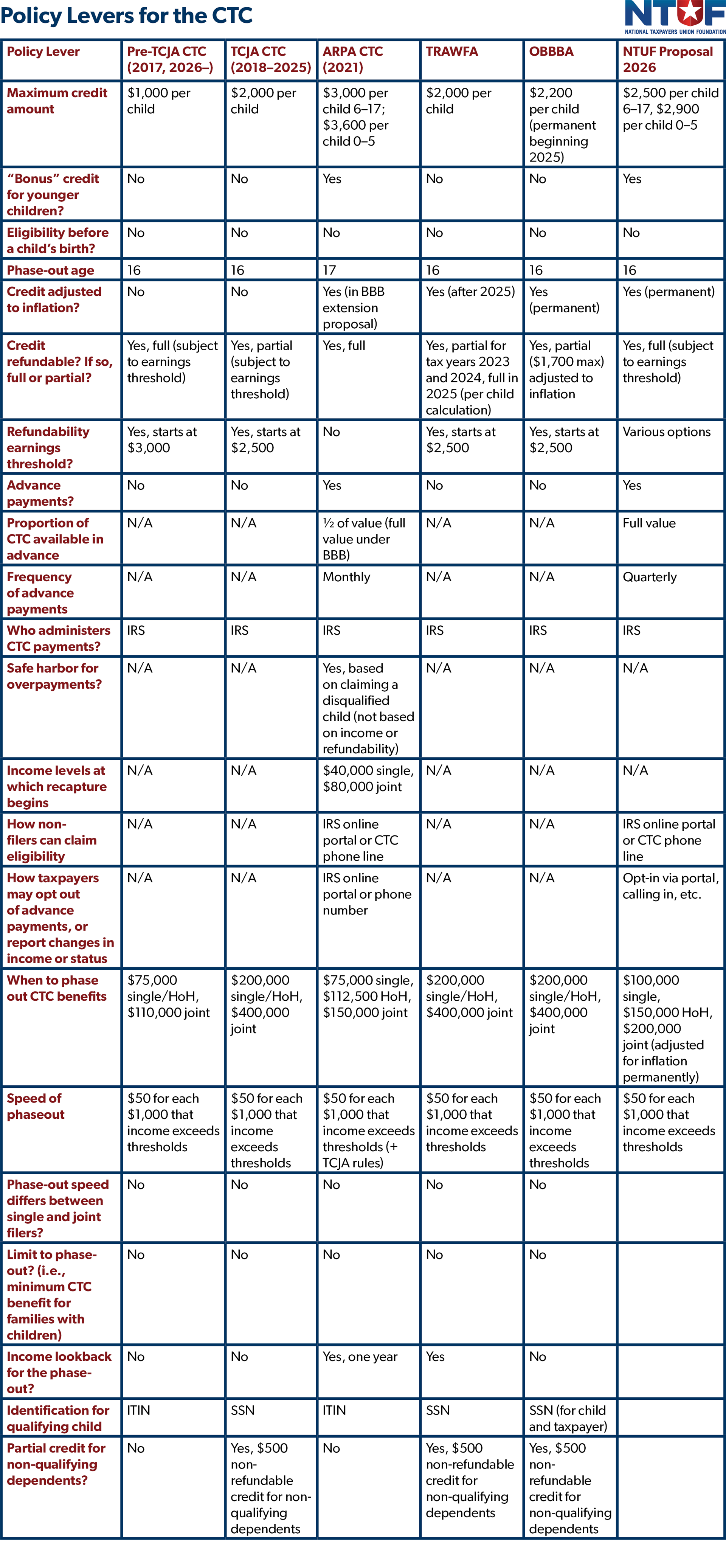

Over the past decade, the Child Tax Credit has undergone two major overhauls: first through the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, then through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021. Both reforms significantly increased the amount of the credit while expanding eligibility.

The TCJA changed the Child Tax Credit on a temporary basis through the end of 2025, when the credit amount would have reverted to $1,000 without OBBBA. Under TCJA, the $2,000 credit amount was double the permanent law amount of $1,000, was partially refundable up to $1,400 in 2018 and adjusted for inflation thereafter, was subject to a minimum earnings threshold of $2,500, and began to phase-out for single taxpayers earning $200,000 or $400,000 for married taxpayers.

Had the credit reverted to prior permanent law, the refundability earnings threshold would have increased to $3,000 and the phase-out would have decreased to $75,000 for single filers and $150,000 for joint filers.

During the pandemic, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 changed the Child Tax Credit only for the 2021 tax year. ARPA increased the credit amount from $2,000 to $3,000 per child and added a $600 bonus for children under age six, bringing the total credit to as much as $3,600 per child. It also adjusted various other policy levers of the credit by making the credit fully refundable with no minimum earnings requirement, delivering payments in monthly advanced payments, and lowering the income thresholds for phaseout to $75,000 for single filers, $112,500 for heads of household, and $150,000 for married couples filing jointly.

Though these reforms occurred under different circumstances, they are indicative of the Child Tax Credit’s bipartisan appeal and political importance. Republicans expanded the Child Tax Credit under a trifecta government as part of a plan to promote economic growth through tax reform. Democrats expanded the Child Tax Credit under a trifecta government to stabilize families’ disposable income amid the COVID-19 pandemic and economic uncertainty. While both of these changes were temporary due to Senate budget reconciliation rules, both expansions served mainly to increase the value of and access to the credit.

In 2024, the Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act (TRAFWA) was introduced by Ways and Means Chairman Jason Smith (R-MO) and Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) as a bipartisan attempt to enhance the Child Tax Credit. TRAFWA also would have calculated the refundable portion on a per-child basis, gradually increased the maximum refundable amount of the credit to the full $2,000, adjusted the credit for inflation for two years, and allowed taxpayers to calculate their maximum Child Tax Credit amount using the prior year’s income for two years.

While TRAFWA was a thoughtful compromise bill, its failure shined light on contentious issues regarding the Child Tax Credit and allowed policymakers more time to consider potential changes. TRAFWA showed that House Republicans were willing to accept full refundability and indexing the credit to inflation. Yet, it also showed that calculating the Child Tax Credit using the prior year’s income, known as the “income lookback rule,” would be too contentious to pass through both chambers.

One Big Beautiful Bill Act

Families filing their taxes for the 2025 tax year will soon benefit from OBBBA’s changes to the Child Tax Credit. OBBBA permanently increased the amount of the Child Tax Credit from $2,000 per child to $2,200 per child retroactively to the beginning of 2025, meaning that families will see the benefit immediately. For the 2026 tax year, families will see a further increase with the credit’s permanent inflation adjustment.

These changes will deliver the most significant improvement to the Child Tax Credit since TCJA. It also marks the first time the base credit amount has been tied to inflation, with previous versions of the credit only indexing the refundable portion to inflation. Not only will the permanent increase in the credit amount provide immediate and lasting relief for families across the country, inflation adjustments will provide additional certainty that the Child Tax Credit can be a reliable source of support for as long as the family remains eligible.

Despite this important progress, the credit amount set by OBBBA remains below what it would be had TCJA’s Child Tax Credit boost been adjusted for inflation. In 2026, the credit would be worth about $2,500 today had it been adjusted for inflation since being set at $2,000 in 2017.

Earlier versions of OBBBA recognized this devaluation, as the House version passed on May 22, 2025 would have temporarily boosted the Child Tax Credit amount from $2,000 to $2,500 for four years. The bill would have made TCJA's $2,000 per child credit permanent so that the credit would revert to TCJA levels after the temporary boost expired instead of the lower pre-TCJA level. The bill would have also permanently adjusted the credit for inflation starting in 2029, after expiration of the temporary increase.

Increasing the credit amount to $2,200 instead of $2,500 came with two major benefits. First, it had a more modest budget impact at a cost of $816 billion over ten years. Second, it also left the door open for further reforms should Congress wish to tackle the Child Tax Credit again as part of a developing affordability agenda.

Alongside increasing the Child Tax Credit, OBBBA enhances other tax provisions targeted toward families. First, it maintains TCJA’s $500 nonrefundable credit for dependents who are not eligible for the Child Tax Credit. Additionally, it enhances the adoption tax credit by permanently indexing both the credit amount and phase-out to inflation, while making up to $5,000 of the adoption tax credit refundable. Finally, the law also expands employer-focused benefits: Section 45F now allows a maximum credit of up to $600,000 for small businesses providing child care, and Section 45S permanently incentivizes paid family leave, offering employers a 12.5% to 25% credit on wages for qualifying leave.

Recommendations to Further Improve the Child Tax Credit

With increasing focus on a second reconciliation package during this Congress, there is both the opportunity and the desire to implement more family-focused tax changes. Because reconciliation is limited to tax and spending legislation, enhancing the Child Tax Credit represents one of the few actionable avenues for supporting families without needlessly bloating the deficit.

While there is no single solution to ensuring the Child Tax Credit works as an effective anti-poverty measure for those most in need while maintaining fiscal responsibility, there are plenty of policy principles to keep in mind when making changes to important parts of the tax code.

Changes that can reinforce the positive impact of the credit include:

- Permanently increase the base amount of the credit to $2,500 and maintain an adjustment for inflation.

- Implement a $400 bonus credit for children age 0–5.

- Make the credit fully refundable with various options for minimum earnings.

- Lower costs by decreasing the earnings at which the credit phases out to $100,000 for single taxpayers, $150,000 for head of household filers, and $200,000 for joint filers.

- Eliminate employer-specific family tax credits.

Permanently increase the base amount of the credit to $2,500 and maintain an adjustment for inflation.

A base credit amount of $2,500 is equivalent to where the credit amount would be had TCJA’s amount been adjusted for inflation since 2017. The House considered this level of Child Tax Credit benefit while crafting OBBBA, but an increase to $2,200 was ultimately what was signed into law. While OBBBA included a permanent inflation adjustment that will keep the credit from further eroding in value, failing to bring the base credit amount up to what it would have been if TCJA’s credit had been tied to inflation effectively serves as a tax increase for families.

Unlike narrowly targeted government programs or one-time cash handouts, the Child Tax Credit gives families predictable financial relief, helping cover costs including food, housing, health care, and energy. Making a $2,500 credit level permanent and keeping it indexed for inflation is a simple and highly popular pro-family option for the next reconciliation package.

Include a $400 bonus credit for children age 0–5.

The Child Tax Credit can also be improved by adding a younger child bonus credit of $400 for children ages 0–5, when parents tend to incur higher costs and have fewer options for daily childcare.

A younger child bonus credit was first introduced by ARPA, and, while that provision quickly phased out, the idea remains popular. In the lead up to the OBBBA debate, there was much discussion among conservatives about how the Child Tax Credit should treat the youngest children.

Ultimately, instead of a bonus for younger children, OBBBA included a provision to give cash to children in the form of Trump Accounts (previously called MAGA Accounts). Trump Accounts are automatically funded with $1,000 for each child born between 2025 and 2028 in an account to which parents can contribute an additional $5,000 annually until the child reaches 18 years old.

While Trump Accounts offer a path toward future savings for today’s infants and children, they do not address immediate concerns about affordability and the cost of expanding a family. A $400 younger child bonus to the Child Tax Credit would provide more immediate benefit to a child’s well-being.

Make the credit fully refundable with various options for minimum earnings.

A permanent credit amount of $2,500 indexed to inflation is critical for fiscal sustainability, fairness, and poverty alleviation. OBBBA also recognizes the importance of the refundable portion of the credit as an anti-poverty measure by indexing the partial refundability amount of $1,700 to inflation, so that the families most in need can also see a stable credit value.

Full refundability within an income range is a laudable goal for several reasons. First, partial refundability restricts few households, and those households that are restricted may see unintended consequences. About 95% of children live in households with earned income, while those that do not typically live in households with a single parent. Some children living in households with no earned income live with guardians who are not their parent or with guardians who are retired or disabled—with these forms of income not being applied to a taxpayers’ earned income for Child Tax Credit calculation purposes.

Second, taxpayers at the lowest earning levels are the most affected by tax complexity. Taxpayers who earn just enough to receive a partially refundable tax credit ($2,500 in earnings annually), yet not enough to receive the full amount, may be confused by headlines stating that the credit amount is now $2,200 per child, yet they are only receiving $1,700 per child. In addition, taxpayers may not be aware of the minimum earnings requirement to be eligible for the refundable portion of the credit, meaning those earning just under that amount may lose out unexpectedly.

Third, scholars have continuously debated the credit’s effect on work without reaching a definitive conclusion. While it is reasonable to expect that some earnings requirement would serve as an incentive for those in the lowest income brackets to stay in the workforce, it is unclear what the ideal minimum earnings requirement should be.

With this in mind, we continue to recommend that the credit be made fully refundable with various earnings options. We previously provided the options to retain the $2,500 earnings threshold, but exempt certain groups of taxpayers: those with children ages 0–5, elderly guardians, guardians with disabilities, or student taxpayers. This would effectively recognize that taxpayers in these situations are most at need and would deliver the anti-poverty benefit most effectively. However, as we previously noted, this would introduce administrative complexity as taxpayers and the IRS attempt to verify these statuses.

In future tax legislation, Congress can still honor these exemptions, but could do so in a more administrable way by simply including retirement and disability income as eligible income for Child Tax Credit calculation purposes. Currently, pensions and annuities, as well as Social Security benefits, are not considered eligible earned income when determining eligibility for the Child Tax Credit.

On one hand, this makes sense: if a taxpayer’s only earnings are from pensions, then they are not working. On the other hand, if a taxpayer’s only earnings are from pensions, then the debate around incentivizing or disincentivizing work presumably does not apply, as this taxpayer is no longer in the workforce anyway. The same is true for disabled taxpayers. Student status could be verified through use of existing tax forms, such as the 1098-T, in lieu of certifications of enrollment.

Policymakers could consider three other suggestions for reforming the earnings eligibility for the refundable portion to help those most in need:

- First, policymakers could reduce the earned income requirement to $1. This ensures that parents making between $1 and $2,499 can still benefit from the credit. The difference between $2,499 and $2,500 is arbitrary. As average hourly wages in the U.S. for the retail sector are about $25, this is the difference between working 100 hours per year and 99 hours and 57 minutes.

- Second, policymakers could make a portion of the credit refundable with no earnings threshold. This option would guarantee that there is at least some benefit for the poorest households, without the administrative complexity of the IRS verifying a taxpayers’ retirement, disability, or student status. Making 75% of the credit fully refundable for all (which would be $1,875 for a $2,500 maximum credit amount) reduces complexity for administrative purposes, but could still be confusing for taxpayers.

- Third, they could convert the existing $500 non-refundable credit for non-qualifying dependents into a refundable credit with no earnings threshold, while allowing parents to choose between the $500 credit or the Child Tax Credit. Providing this flexibility would better alleviate complexity for both taxpayers and the IRS, yet a $500 credit would be significantly less than the $2,500 Child Tax Credit and taxpayers may have a difficult time understanding which choice is best for them given the complexity of the credit and their financial situation.

Lower costs by decreasing the earnings at which the credit phases out to $100,000 for single taxpayers, $150,000 for head of household filers, and $200,000 for joint filers.

A future reform could be an opportunity to reduce the cost of the Child Tax Credit by adjusting the higher phaseout thresholds set by TCJA and maintained in OBBBA. TCJA raised the income level at which the credit begins to phase out from $75,000 for single filers and $110,000 for joint filers to $200,000 for single filers and $400,000 for joint filers.

Recent adjustments ultimately changed who benefitted the most from the Child Tax Credit, with 25% of the credit going to households earning between $100,000 and $200,000 in 2022. These taxpayers also receive the largest overall credit, on average, at over $3,000. If the goal of the credit is only to assist all households with the expenses of a growing family, then policymakers could make the credit available to everyone regardless of income. Yet, the Child Tax Credit has never been structured this way. The Child Tax Credit was designed, in part, to reduce taxes for lower-income families that did not benefit from tax exemptions in place at the time.

Policymakers must also balance family assistance with fiscal discipline. Ensuring that the neediest families receive benefits while reducing the fiscal impact of the credit necessitates cutting off eligibility at some income level. Had the earnings phaseout remained at $75,000 for single filers through TCJA and been inflation-adjusted, those taxpayers would experience a phaseout at around $97,000 annual income now. For married filers, if the earnings phaseout had remained at $150,000 and been adjusted to inflation, those filers would see the phaseout begin at around $194,500 today.

A phase-out level of $100,000 for single filers, $150,000 for head of household filers, and $200,000 for joint filers is now appropriate.

Eliminate employer-specific family tax credits.

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that OBBBA decreases revenue by $6.2 billion over ten years due to increases for the employer-specific tax credits targeted toward families, known as Section 45F and Section 45S. Ending these niche and restrictive tax breaks would help pay for some of the cost of expanding the Child Tax Credit.

Conclusion

The Child Tax Credit should be front and center in upcoming discussions to build upon the success of tax reform.

OBBBA’s expansion of the Child Tax Credit is a win for taxpayers who will see the benefit imminently as tax season approaches. The benefit to families of permanently increasing the amount of the Child Tax Credit and indexing it to inflation through OBBBA cannot be overstated. However, bringing the credit amount up to what it would be if it had been adjusted for inflation since 2017 would bring further support to families and the tax code, while reinforcing Republicans’ commitment to strengthening the family unit.

The Child Tax Credit is not an all-in-one solution to the most pressing issues facing young families today, but it is an important tool with unique benefits. Its administrative simplicity relative to other government programs and neutrality compared to other parts of the tax code make it vastly popular, as is demonstrated by its consistent bipartisan support. It can also be expanded in a manner that is fiscally responsible and would likely have more broad-based impact than other affordability proposals currently on the table.