(pdf)

Introduction

Since the late 1970s, the consumer welfare standard and economics-focused U.S. competition policy approach has provided an effective legal framework for promoting technological innovation and consumer welfare while addressing anticompetitive conduct.[3] However, U.S. competition policy increasingly appears to be at a crossroads as antitrust regulators and some lawmakers seek to move the country away from decades of bipartisan antitrust consensus. As the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) continue to reshape U.S. antitrust law without explicit Congressional authorization, U.S. lawmakers have done little to hold these agencies accountable.[4] Instead, a small but growing faction of lawmakers now seeks to upend the U.S. antitrust tradition by advocating laws that could hamstring innovation while introducing new privacy and security risks. As the United States braces for yet another heated, increasingly partisan political season in the run-up to the 2024 Presidential Elections, maintaining a sensible, evidence-based approach to competition policy is more important now than at any other time in recent years.

A better understanding of recent trends in the U.S. competition landscape is helpful to understanding the growing challenges to a dynamic digital economy sector. More specifically, there are two separate but related challenges to traditional U.S. antitrust policies. The first challenge comes from the Federal Trade Commission and, to a lesser degree, the Department of Justice — which seek to reshape U.S. competition law by jettisoning its traditional focus on consumer welfare in favor of a more ideological, politicized approach.[5] While courts have played an important role in constraining the FTC and DOJ’s regulatory overreach, Congress will ultimately need to step in by holding them accountable.

However, the more substantial, longer-term challenge comes from within Congress itself. In the 117th Congress, at least two bills would have significantly curtailed virtually all mergers and acquisition activities (M&A) by large technology companies.[6] If passed, such policies would not only hamstring the abilities of large U.S. firms to acquire new technologies, but they would also restrict exit options for start-up founders. Although many such overly restrictive bills were ultimately not passed, future laws along these lines could create significant challenges for the U.S. regulatory environment.

Some of the less restrictive proposed laws would also introduce new unintended consequences for many areas of online life beyond antitrust.[7] For example, two recent bills proposed to mandate data portability and interoperability between different dominant online platforms.[8] In the absence of a federal privacy framework, such requirements can easily introduce substantial data breach and cybersecurity risks for U.S. and non-American users of U.S. online platforms.[9] At a time when the United States is increasingly gaining a global reputation as a jurisdiction with substandard privacy protections, such developments could further reduce the attractiveness of the U.S. regulatory environment.

Recognizing the two-pronged challenge to the future of U.S. competition policy, this report is structured as follows. First, it discusses why a permissive regulatory environment for mergers and acquisitions is essential to technological innovation and consumer welfare. Second, it analyzes the FTC’s changing antitrust role under the Biden administration and the challenges that it poses to the U.S. digital economy sector. To that end, the brief provides a timeline of the FTC’s growing deviation from bipartisan antitrust consensus under its new leadership.[10] Third, it discusses problematic aspects of recent antitrust legislation and how they should inform future U.S. competition policy. Finally, the report concludes by briefly discussing the role that Congress can play in maintaining the traditional, evidence-based U.S. antitrust approach and ensuring a more dynamic, globally competitive U.S. digital economy.

The Need for Permissive, Innovation-Friendly Competition Policy in the Context of the U.S. Digital Economy

While certain traditional business conduct can be anticompetitive and harmful to consumers, existing statutes and case law are generally well-developed to address such harm. More specifically, the Clayton Act, the FTC Act, and the Sherman Act, and court decisions provide an extensive body of rules and legal precedents well-equipped to address anticompetitive conducts of dominant firms, as well as online fraud and deception.[11] Indeed, these are areas where the FTC and the DOJ have an important role as enforcers of existing competition law and other applicable statutes.[12] In the future, a well-designed federal privacy law can also help mitigate emerging policy challenges related to privacy and data security malpractices and better define the FTC and the DOJ’s role in such domains.

While legitimate competition policy concerns should be addressed through appropriate legislative and regulatory channels, they should not detract from the benefits of a more permissive, evidence-based antitrust approach. Given the extensive body of scholarship on the benefits of market-friendly antitrust policies for the broader economy, this report does not discuss such benefits in detail.[13] Instead, this section briefly discusses why a permissive, innovation-friendly regulatory environment is particularly important in the context of the U.S. digital sector.

Implications for Technological Innovation by Large Firms and Consumer Welfare

The practice of mergers and acquisitions in the technology sector is paramount to economic development and innovation. As start-ups scale, they often lose their earlier innovativeness. Acquiring new start-ups can help larger companies acquire new technologies and business models and remain on the cutting edge despite their larger size. For instance, although apps like Instagram and TikTok are often innovative in the early days of their founding, they risk falling behind newer entrants as they scale up. Acquisitions can help such apps acquire new tools and capabilities that allow them to remain innovative despite their larger size.[14]

Likewise, mergers and acquisitions can help firms improve structural weaknesses, develop new niches, and enter new markets. One demonstrative example is Amazon’s acquisition of the Austin-founded Whole Foods Market for approximately $13.7 billion in 2017, which allowed Amazon to enter the retail food market while gaining physical infrastructure for in-store pickup and retail facilities.[15] Without a regulatory environment that allows this commercial dynamism, tech companies risk becoming less innovative as they age and fall behind new competitors from other sectors and foreign jurisdictions, who might not be subject to the same regulatory restrictions.

Although causal links remain challenging to establish in antitrust analysis, case studies of specific market segments provide insights into how competitive pressure from mergers and acquisitions often promotes innovation and consumer welfare. According to the Congressional Research Service reports, Amazon’s entry into the retail food market via its acquisition of Whole Foods likely increased competitive pressures on other grocery retailers like Kroger and Walmart, who sought to compete with Amazon by offering grocery delivery services online.[16] For instance, during the same year that Amazon acquired Whole Foods, Walmart launched its online delivery service in selected U.S. cities, while Kroger launched a similar delivery service for some U.S. cities the following year. Likewise, to compete with Amazon Prime, Walmart launched “Walmart+” — a membership-based delivery service without a minimum order requirement for deliveries.[17] Meanwhile, newer Instacart and UberEats have also begun to offer delivery without extra charge for orders beyond a certain threshold.[18]

In the aforementioned cases, companies were largely able to offer these products and services due to a broadly permissive antitrust regulatory environment in the last few decades. The recent developments in the retail food market serve as one example where market-friendly antitrust policies and the resulting competitive pressure for incumbent firms and new entrants can benefit consumers through greater consumer choice, low prices, and better services. These benefits do not preclude the possibility that specific anticompetitive conduct by dominant firms can result in consumer harm in certain instances. Such harms should be addressed appropriately within the scope of existing antitrust law rather than jettisoning the current antitrust approach in favor of an overly restrictive one.

Implications for Technology Start-ups and Entrepreneurs

Notwithstanding some concerns, mergers and acquisitions can be largely beneficial for start-ups. A general perception among some management scholars is that dominant firms acquire start-ups because they represent future competitors. In the aftermath, erstwhile innovative start-ups flounder and ultimately fail — a phenomenon that management professors from the London Business School and Yale School of Management have termed “killer acquisitions.”[19]

This issue remains a highly complex one, as the eventual success of a start-up depends on the complex interplay of various factors, such as its market environment, technological strengths, business strategy, and managerial efficiency. Eventually, many start-ups and new business models fail, irrespective of whether another firm has acquired them. That said, the rate of failure is likely to be lower for acquired start-ups since i) they likely have already demonstrated some success that led to buyout offers, and ii) they can draw from the expertise and resources of the acquiring firm.[20] Whether a specific merger or acquisition contributed to a start-up’s long-term success or failure is a highly fact-intensive, context-dependent enterprise, the results of which are difficult to generalize for firms across the economy.

However, with the right business strategy, acquisitions can enable start-ups to manage their strategic challenges more successfully as they scale up. Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram, another social networking platform, provides an interesting case study case in this context. Facebook acquired Instagram for $1 billion in April 2012, when Instagram was a relatively new and innovative social media platform with a fraction of its current user base. Following the acquisition, Instagram’s user base grew from 100 million monthly active users in February 2013 to 500 million users in June 2016, ultimately reaching a billion users in June 2018.[21] As Instagram’s user base multiplied, the app was able to utilize Meta’s digital infrastructure and technological know-how, which has been instrumental to Instagram’s profitability as a social media platform.[22]

Despite this success, whether Instagram would have succeeded on its own and eventually gone on to rival Facebook or eventually floundered is a counterfactual question that remains difficult to evaluate.[23] With an appropriate business strategy and financing from venture capital firms or through an eventual initial public offering, it is possible that Instagram might have eventually eclipsed Facebook’s popularity as a social media platform while remaining an independent company. However, it is also possible that, like other social media platforms, Instagram might have struggled to compete globally because of potential resource constraints and operational difficulties.[24]

In 2003, an erstwhile popular social media platform called Friendster rejected a $30 million buyout offer from Google.[25] As Friendster’s user base grew, it suffered technical and operational difficulties, and users began switching to other platforms. Such difficulties, along with management failures and intra-company clashes, contributed to the eventual decline of the platform and its shutdown in 2015.[26] Whether start-ups succeed depends on a whole range of factors, including business strategy and the market environment, which go beyond the policy question of mergers and acquisitions. Ultimately, such business decisions should be left to the devicesof start-ups and founders — not regulators or lawmakers — who should make informed decisions based on their strategic objectives and available information.

Likewise, permissive antitrust policies make it easier for start-up founders to develop and sell their companies for a high price. Contrary to popular perception, only a minority of U.S. start-up founders intend to launch the next technological behemoth. On the contrary, the majority of U.S. founders seek to scale and sell their companies and use the proceeds for new ventures.[27] In a permissive regulatory environment, competing bids from different tech companies and venture capital firms drive up the valuation of start-ups. This lucrative exit option attracts more entrepreneurs, contributing to the creation of new start-ups and a more dynamic tech ecosystem.[28]

A comparative view of the U.S., UK, Canadian, and Chinese start-up financing ecosystems provides additional insights into why a permissive antitrust approach is essential in the U.S. context. According to the 2020 Startup Outlook Survey, 58 percent of U.S. start-up founders listed being acquired as the most realistic long-term goal, while only 17 percent planned to take their companies public through an IPO, and another 14 percent intended to keep their company private.[29] These figures are also broadly similar for start-ups in Canada and the UK but not in China, where the trend is roughly the inverse.[30] In contrast, 46 percent of Chinese start-up founders saw going public via an IPO as the most realistic long-term option, whereas only 14 percent and 21 percent of entrepreneurs expected their companies to be acquired and remain public, respectively.[31]

These numbers largely reflect the available financing options for start-ups in different ecosystems. Notwithstanding the increasingly unfriendly regulatory environment and economic difficulties in China, the country’s initial public offerings have raised five times as much money as those in the United States in the first half of 2023.[32] As China has emerged as the world’s largest IPO market, initial public offerings have understandably become the most popular exit plan for Chinese entrepreneurs.[33] In contrast, against the backdrop of a more lackluster IPO market, buyouts remain the most viable exit options for most U.S. start-ups.

That is another reason why maintaining a more flexible approach to antitrust policy is more important in the United States than in countries with thriving IPO markets. Nevertheless, some recent legislation sought to impose blanket restrictions on merger and acquisition activities, which would further dampen the regulatory outlook for U.S. tech firms and start-ups.[34] If such restrictions were implemented along with restrictive policies in other domains, they could significantly reduce the country’s regulatory attractiveness for U.S. and foreign companies.

The Federal Trade Commission’s Efforts to Reshape U.S. Privacy Law without Explicit Congressional Authorization

Regulators play a vital role in maintaining a permissive, evolving, and flexible regulatory environment for the digital economy. However, developing and maintaining such an environment is challenging for several reasons. First, as the Congressional Research Service points out, antitrust law remains a highly fact-specific and context-dependent domain, even when compared to other areas of law and policy. For example, the lack of clarity about the definition of the relevant market and what constitutes unfair conduct leads to considerable uncertainty for businesses. That is especially the case since the legality of specific business activities may ultimately hinge not on the behavior itself but on whether regulators deem the companies involved as having enough market power to render such behavior unlawful.[35]

Second, the rapidly changing technological landscape means regulators have a crucial role in applying relevant laws and ensuring an innovation-friendly environment while addressing anticompetitive conduct. The rapid growth of new technologies and business models means market structures can change much more quickly than in sectors with less exposure to technological change. As a result, it is complicated for legislators to predict future changes and write detailed competition laws for different sectors — meaning that overly prescriptive laws in a rapidly changing market are often counterproductive.

That is why, in jurisdictions such as the United States, regulators often have an essential role in applying and enforcing competition rules in the context of specific sectors. That is done by issuing regulations within the scope of laws passed by Congress. Courts may act as a further limiting source by weighing in on conflict of law issues and helping to clarify otherwise opaque statutory text. The combined effect of Congress, regulators, and the Courts is a delicate balance necessary to ensure a thriving digital ecosystem against the backdrop of emerging technologies and business models. However, such a system only works when regulators carry out their role while respecting the limits of their power.

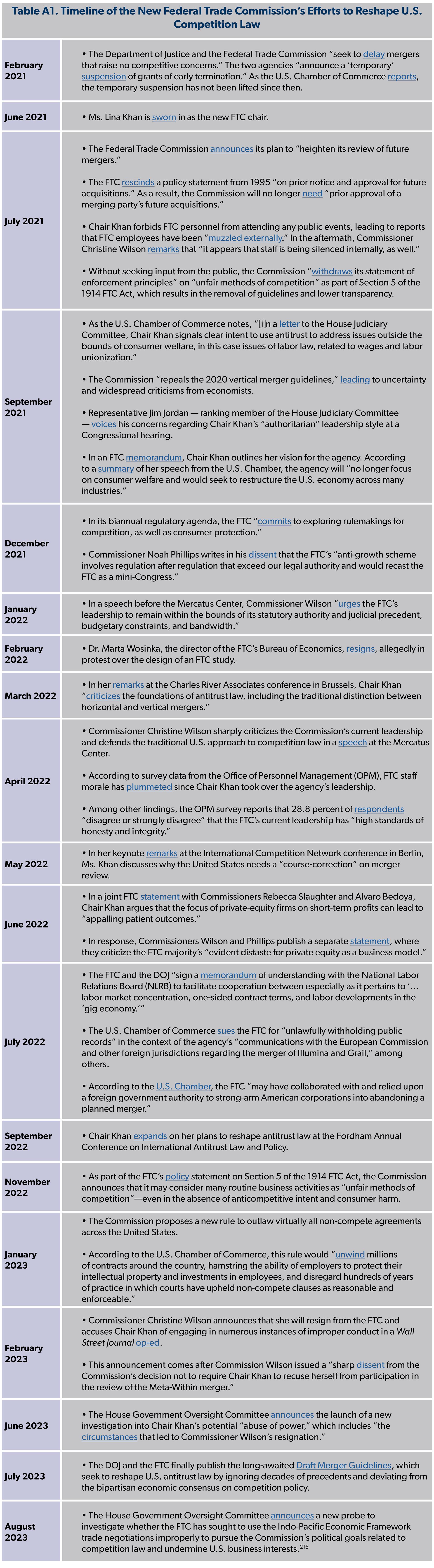

For a regulatory agency like the FTC, this limit means it must confine its efforts to that which concerns the agency and should not seek to rewrite American competition law beyond the bounds created by Congressional laws. Instead, it should enforce current laws as they exist in statutes. Nevertheless, under the FTC’s increasingly doctrinaire leadership, the agency continues to reshape U.S. competition law beyond any powers granted by Congress (Table A1). As a result, an overly activist FTC represents the most immediate challenge to traditional U.S. competition policy and a permissive regulatory environment. That is why U.S. lawmakers should seek to understand the FTC’s growing challenges for the U.S. digital economy sector, which are discussed in greater detail in this section.

The FTC’s Disregard for the Consumer Welfare Standard as a Cornerstone of U.S. Competition Policy

Following the overly activist U.S. approach to antitrust and its adverse economic effects, U.S. Courts and regulators adopted the consumer welfare standard and pursued an economics-focused approach to antitrust policy since the 1970s.[36] Since then, the consumer welfare standard has provided a predictable and effective legal framework for U.S. competition policy. In recent decades, successive Democratic and Republican administrations — including under Presidents Obama and Trump — have pursued this approach, which also enjoyed support from broad swathes of FTC commissioners and staff members alike.[37]

However, under the aegis of Chair Lina Khan, the FTC has gradually sought to move away from this decades-long bipartisan economic consensus. While Chair Khan, a professor on leave from Columbia Law School, is no doubt a noteworthy legal scholar, she has increasingly sought to fundamentally reshape U.S. antitrust law — a role that belongs to Congress, not regulators.[38] In a letter that Chair Khan sent to the FTC staff shortly following her appointment, in which she outlined her vision of U.S. antitrust policy, she rejected the consumer welfare standard as a “somewhat narrow and outdated framework.”[39] Instead, Chair Khan advocates a “holistic” approach to competition policy, which prioritizes the interest of “workers” and “independent businesses” in addition to consumers.[40]

According to Chair Khan, antitrust enforcement should also address broader issues of the U.S. digital economy, including “power asymmetries,” “structural dominance,” and “rampant consolidation.”[41] To that end, Chair Khan also expressed her intention in a letter to the House Judiciary Committee to use competition policy tools to “address issues outside the bounds of consumer welfare,” including labor law issues like unionization and wage determination.[42] As a result, the FTC now appears to be asking businesses questions related to corporate governance, environmental standards, and corporate governance. [43] While environmental and labor policy questions are important ones, these belong to the domain of Congress and the respective agencies, not the FTC. This growing change in direction signals the FTC’s efforts to jettison its traditional antitrust focus and instead instrumentalize antitrust policy tools to pursue political objectives in domains far beyond the agency’s remit.

The FTC’s Growing Focus on “Structural Factors” Instead of Actual Evidence of Anti-Competitive Conduct and Negative Effects on Consumers

Instead of focusing on evidence of anticompetitive conduct, the FTC appears to increasingly focus on poorly defined structural factors in antitrust enforcement.[44] Such an approach poses several major challenges. First, despite the FTC’s growing focus on “structural” factors and “root causes” of industrial concentration, they are often poorly defined, increasing the risk of exacerbating market uncertainties. By shifting its focus away from economic analysis, this approach also enables the FTC to punish companies in politically “disfavored” industries like technology and healthcare.[45]

Second, the lack of economic consensus about the relevant market means that the FTC can define the market in a way that overstates the dominance of a given company.[46] One prominent example is the FTC’s decision to adopt an overly narrow definition of the relevant market in its ongoing litigation against Amazon. By defining the relevant market as an online superstore market, the FTC effectively excludes physical retail stores with a significant online presence, as well as physical retail stores, with which Amazon also competes for retail shopping.[47]

The “relevant market fallacy” problem of U.S. competition policy has only been exacerbated under the FTC’s approach.[48] Instead of focusing on whether specific business activities are anti-competitive and negatively affect consumers, the growing emphasis on structural factors and politically expedient definitions of markets risks paving the way for an increasingly politicized, arbitrary approach to U.S. competition policy.[49]

Finally, the FTC’s jettisoning of the consumer welfare standard means that the agency’s enforcement actions are increasingly based on speculative arguments instead of evidence of consumer harm.[50] As Sean Heather of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce explains, one such example is the recent FTC lawsuit related to Amgen’s acquisition of Horizon Therapeutics. More specifically, Amgen — a California-headquartered biotech company with an annual revenue of $26.3 billion in 2022 — agreed to acquire Horizon Therapeutics, a smaller biotech company with a reported revenue of $3.63 billion.[51]

As part of the agreement, Amgen would gain Horizon Therapeutics’ capabilities to manufacture medicines for chronic refractory gout and thyroid eye disease.[52] No company except Amgen has heretofore received regulatory approval to produce these “orphan drugs”— a designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to encourage the development of drugs for rare diseases and medical conditions.[53] This acquisition would allow Amgen to scale up the production of such drugs and complement Horizon’s strategy of delivering medicine for rare diseases.[54] Increased production can also be significantly beneficial for consumers since no other company has FDA authorization to produce such drugs.[55] Therefore, because of the potential to scale up the production capacity of such drugs, there is a strong consumer welfare argument in favor of the deal.

Notwithstanding such potential benefits, the FTC sought to block the transaction. In the lawsuit, the Commission acknowledged that Horizon had no competitors for the production of these two drugs.[56] However, according to the FTC, if any of Horizon’s competitors were to receive FDA approval eventually, Amgen could then offer pharmacies rebates and discounts on a range of drugs.[57] In turn, that would theoretically allow Amgen to charge high prices for both drugs in such a scenario.[58] This argument is based on the argument that i) other companies might also apply for an FDA license, ii) Amgen would respond by engaging in certain predefined business activities, and iii) those activities would be illegal.[59] However, the opposite may also be true. For example, it could be the case that i) no rivals apply for any FDA license or that ii) Amgen responds by scaling production, cutting drug prices, and pursuing other competitive strategies within the bounds of competition law. The FTC’s decision also ignores potential consumer benefits in the form of expanded availability and lower drug prices.

While it remains unclear whether the lawsuit will ultimately succeed in the courts, it indicates the FTC’s willingness to block mergers based on scarce evidence, even in cases where potential benefits to consumers could be significant.[60] If such efforts succeed in stopping companies from offering new products or services, it could pose a serious long-term challenge to innovation and consumer welfare. Such a development would be especially concerning in an increasingly competitive global market where U.S. companies compete increasingly with their international counterparts.

The FTC’s Approach to Merger Review and Challenges for U.S. Competition Policy[61]

The FTC’s approach to mergers and acquisitions is a further case study of the challenges associated with the agency’s move away from the bipartisan antitrust consensus. As the agency seeks to reshape U.S. competition law, Chair Khan and her progressive counterparts have recognized merger review as an essential policy tool. Indeed, as Chair Khan has remarked before the International Competition Network in Berlin, the United States needs a “course-correction” on merger review.[62] This change underscores the new FTC’s efforts to target “root causes” of consolidation and to restrict M&A activities — without regard to whether specific mergers promote competition and innovation.

The FTC’s doctrinaire approach has contravened standard agency norms and increased polarization in an agency characterized by bipartisan collaboration and collegiality. In July 2021, a month after Chair Khan’s appointment, the FTC rescinded a prior policy statement from 1995, without any public comments, on notice and approval requirements for future acquisitions (Table A1).[63] As a result, companies were required to seek prior FTC approval of future acquisitions, resulting in dissent from the two minority Commissioners.[64] Likewise, in November 2021, the FTC released a report on merger and acquisition activities, which was criticized for the politicization of typically fact-based reports and for using such findings to advocate sweeping changes to merger review.[65] The two Republican-appointed minority Commissioners — Christine Wilson and Noah Joshua Phillips — went on to argue that the majority Commissioners “are destroying the merger review framework established by Congress and displacing actual antitrust enforcement.”[66]

Most recently, in June 2023, the FTC and the DOJ issued the most recent merger review guidelines.[67] Since 1968, merger review guidelines issued jointly by the Department of Justice and the FTC have played an essential role in improving transparency and promoting awareness regarding U.S. antitrust policy.[68] As a result, merger review guidelines — like the ones issued in 2010 under President Obama — are beneficial to companies as a source of guidance in understanding how they should achieve regulatory compliance with existing laws.[69]

In lieu of providing such clarification, the new guidelines seek to upend well-established antitrust practices and legal assumptions and create new competition rules. For example, the seventh and eighth rules of the merger guidelines stipulate that mergers “should not entrench or extend a dominant position” and “should not further a trend toward concentration.”[70] Such broad provisions suggest that any merger activity by a sufficiently large firm could be declared illegal by the FTC without considering how it would affect market structure, competition, and consumer welfare.[71] Likewise, under the first rule, firms with as little as 30 percent market share could come under the commission’s regulatory crosshairs for mergers or acquisitions of any size.[72]

This overly broad scope of the guidelines — combined with the absence of detailed guidance — means that they will be of limited value to companies seeking to comply with existing antitrust statutes. Instead, the guidelines appear designed to grant an increasingly ideological FTC the power to block any potential merger or acquisition.[73]

The Erosion of Agency Norms and Traditions under the FTC

The growing erosion of agency norms and traditions also appears to be a key characteristic of the FTC. As former Commissioner Christine Wilson points out, the FTC has been long marked by non-partisanship, open dialogue, and civility. This bipartisan tradition has largely been the product of agency norms and practices — such as the emphasis on the consumer welfare standard, rulemaking processes that value public input and impartiality, and the agency’s appreciation for the limited jurisdiction as set by Congress.[74] However, such practices have been under attack under the current FTC.

To a certain extent, this trend began shortly before Chair Khan’s tenure. In 2018, Rohit Chopra was appointed as an FTC commissioner, a role in which he served until 2021.[75] Commissioner Chopra — who is a mentor to Chair Khan and previously hired her as a legal fellow — quickly gained a reputation for his vitriolic attack on both the FTC and its staff.[76] Under his tenure, attacks against the bipartisan antitrust approach grew, with Commissioner Chopra suggesting that FTC staff were “captured by the industries they oversaw.”[77] Having been known for distrusting FTC staff, he also suggested that the Commissioner’s Inspector General should review staff’s output related to mergers in the pharmaceutical industry.[78] He went on to serve as the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau,[79] where he remarked that financial regulators are often “corrupt lawyers and economists” who merely use their current position for future private sector jobs.[80] Unsurprisingly, Chair Khan has also adopted a similar outlook, suggesting that the Department of Justice employees who seek to join large financial institutions “may hesitate to antagonize a potential employer.”[81]

This worldview –- based on a deep-rooted distrust of non-partisan, evidence-based antitrust policy –- helps understand recent FTC developments.[82] A month after Ms. Lina Khan became the FTC chair, she removed internal transparency checks intended to prevent overly aggressive investigations and eliminated safeguards, providing her with more control over Section 18 rulemaking procedures for “unfair” or “deceptive” practices (Table A1).[83]

Around the same time, as Chair Khan made the highly unusual move of forbidding agency personnel from attending public events, news reports grew that FTC staff were being “muzzled internally.”[84] Meanwhile, due to the sidelining of agency personnel and the growing lack of input in agency rulemaking, then-Commissioner Wilson observes that FTC personnel “are being silenced internally as well.”[85] In the following months, as the FTC further continued its efforts to concentrate power at the top and suppress meaningful dialogue, the FTC’s problems became quickly apparent — with the House Judiciary Committee ranking member Jim Jordan expressing his concerns about Chair Khan’s “authoritarian” leadership style during a hearing in September 2021.[86]

Unsurprisingly, such changes have driven a decline in employee satisfaction and high-profile departures from the agency. The FTC has traditionally been one of the federal agencies with high employee satisfaction and approval ratings — a trend that has reversed under Chair Khan’s leadership. Recent Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS) results are particularly concerning in this context. In a survey of more than 500 FTC employees, the FEVS results indicate that overall satisfaction of agency personnel has declined from 89 percent to 60 percent between 2021 and 2022.[87] Likewise, the share of respondents who did not have a “high level of respect” for senior FTC leaders increased from 6 percent to 35 percent during the same period.[88] Against this backdrop of low employee morale, it is not surprising that many of the FTC’s talented lawyers and economists are leaving the agency.[89]

Jettisoning of Due Process in the Federal Trade Commission

The FTC has also been increasingly willing to abandon due process in pursuit of its objectives, three aspects of which are of note. First, the Commission has become more willing to discard procedural rules. The same month that Chair Khan became FTC chair, the Commission ignored statutory deadlines under the Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) Act in settling disputes related to 7-Eleven’s acquisition of nearly 4,000 retail stores — causing additional costs and creating legal uncertainty for affected parties.[90] Since then, the agency has failed to respect the statutory deadline to respond to HSR pre-merger notification by M&A parties on multiple occasions. The FTC has also announced that it will send “pre-consummation warning letters” to companies that the Commission fails to investigate within the HSR deadline, raising the possibility that the FTC can use the excuse of filing surge to ignore its legal obligation and keep investigations longer than the statutory deadline.[91]

Second, the Commission has sought to bypass public comments and provide a limited notice window, purportedly to avoid scrutiny of its rulemaking decisions. For example, the Commission’s recent decision to rescind the 1995 policy statement and mandate prior approval for future acquisitions, as well as its withdrawal of the agency’s enforcement principles statement related to “unfair methods of competition” under the 1914 FTC Act, were both conducted without any public input.[92] These policies have enabled the FTC to become aggressive in antitrust enforcement without public input, which is typically characteristic of such decisions.[93]

Third, the FTC repeatedly attacked merger guidelines for being insufficiently aggressive and repealed the 2020 vertical merger guidelines in September 2021 — without providing any alternative set of merger guidelines. The FTC and the DOJ would not release the joint draft merger guidelines until July 2023 (Table A1). Even then, the overly vague merger guidelines appear to have little guidance value for firms.[94] According to a recent survey from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 87 percent of respondents believe that the new merger guidelines do not reflect existing antitrust laws.[95] Repealing previous merger guidelines while delaying the timely publication of new guidelines further suggests how an increasingly arbitrary antitrust approach can exacerbate legal uncertainties for firms.

Declining Ethical Standards in the FTC

Along with the Commission’s growing disregard for due process, ethical issues have become a major concern in the FTC. These concerns have become especially important in light of Chair Khan’s decision not to recuse herself in the Meta-Within case and the circumstances leading to former Commissioner Wilson’s resignation. More specifically, in February 2023, a month before announcing her resignation, then-Commissioner Wilson criticized Chair Khan in a highly critical Wall Street Journal op-ed for her “defiance of legal precedent, and her abuse of power to achieve desired outcomes.”[96] She also expressed her concern that Chair Khan did not recuse herself from the case involving Meta’s acquisition of Within, a virtual reality (VR) developer.[97]

In response to Meta’s petition, the FTC argued that, despite Chair Khan’s prior statements about Facebook, she did not need to recuse herself because the case involved Meta, which involved a “different acquiring company” and a “different industry.”[98] In a previously confidential FTC memorandum –- which was later published by the FTC — Chair Khan wrote that none of her “prior statements that Meta cites in support of its petition even involve any of the relevant markets or products being reviewed here, let alone the ‘same facts and issues.’”[99] Before a House panel in April, Chair Khan also confirmed that she had checked with the Ethics Office whether she should recuse herself in cases where companies like Amazon and Facebook petitioned for her recusal — which was the case for the FTC’s Meta-Within review.[100]

However, recent evidence came to light that the FTC’s ethics official had actually advised that Chair Khan should be recused.[101] Although the advice of ethics officials is not binding, the official went on to add that “no FTC employee has participated in a specific party matter when the agency designee has recommended recusal on appearance or other federal ethics grounds.”[102] Against this backdrop, there have been growing calls to investigate the FTC’s ethical compliance in its enforcement decisions. Most recently, in June 2023, the House Oversight Committee launched an investigation into the circumstances around Commissioner Wilson’s resignation and whether Chair Khan had abused her powers as FTC chair.[103]

Nevertheless, the Commission has dismissed such investigations as “nothing more than a coordinated effort between Big Tech monopolies and their allies in Washington to intimidate public servants.”[104] While the outcome of such investigations and whether they will amount to any change in the FTC’s approach remains to be seen, FTC employees also appear to share U.S. lawmakers’ ethics-related concerns. According to a recent Federal Employment Viewpoint Survey, the share of employees who disagreed with the statement that the agency’s leadership maintained “high standards of honesty and integrity” increased from six percent in 2021 to 35 percent in 2022.[105] Such developments indicate serious concerns about the direction in which the agency is headed under Chair Khan and calls for increased Congressional scrutiny.

Concerns about the FTC’s Role in Cross-Border Regulatory Engagement and Trade Negotiations

Finally, the FTC’s recent efforts to export its political values through international collaboration and trade negotiations have become another source of concern. For example, in recent years, the FTC has sought to pursue international engagement by collaborating with foreign regulators, particularly the European Union. Against this backdrop, some policymakers have opposed the FTC’s growing international efforts; however, such opposition tends to be based on the premise that international regulatory cooperation is per se harmful.[106] However, the policy discussion would benefit from a better understanding of the precise contexts in which the FTC has engaged with its foreign counterparts and evaluating whether such engagement has had positive or adverse effects.

In many contexts, cross-border regulatory cooperation can help design policies that promote consumer welfare and innovation. For example, in the context of AI governance, regulatory cooperation can allow different governments to share best practices in developing risk assessment frameworks and enhancing scientific and research collaboration. Likewise, multilateral institutions like the Organisation for International Economic Cooperation (OECD) provide an important platform for developing international AI norms and principles that OECD members like Japan and the UK have contributed to and borrowed from in the formulation of their national AI policies.[107]

Likewise, in the U.S. context, regulatory cooperation can help develop innovative policy solutions — as was the case with designing U.S. financial technology (fintech) regulatory sandbox programs. When the Arizona government sought to develop the country’s first state-level regulatory sandbox programs, its regulatory cooperation with the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority enabled the state’s policymakers to design the country’s first fintech sandbox.[108] Such efforts demonstrate how cross-border regulatory cooperation can help design beneficial policies that draw from regulatory learning in foreign jurisdictions.

However, that has unfortunately not been the case with the FTC’s international regulatory efforts in the context of competition policy. More specifically, under Chair Khan’s leadership, the FTC has sought to aid the European Commission — the EU’s executive arm — in implementing the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA), the protectionist provisions of which could hamper the long-term innovation potential of U.S. companies.[109]

Indeed, there are growing concerns that the FTC is pursuing such initiatives to punish U.S. companies that the agency disfavors — but against whom the FTC would have only a weak case under U.S. law. However, by aiding the European Commission (EC) in its enforcement efforts, the FTC could help the EC constrain such U.S. companies in the single market. That would provide a roundabout way for the FTC to pursue its regulatory objectives at a time when its litigation efforts have faced multiple defeats in U.S. courts.

However, such an approach risks constraining U.S. innovation and strengthening international norms toward more restrictive competition policies, representing a particular challenge in transatlantic economic and tech relations. At a time when Europe has struggled to produce successful tech companies and risks falling further behind China and the United States, more restrictive policies would hardly be in European interests.[110]

Instead of hamstringing the EU’s digital economy further by encouraging restrictive competition policies, the Biden administration should encourage better European policies. Of course, such initiatives should be done diplomatically and with respect for the sovereignty of the EU and member states. The Biden administration’s recent statement regarding the EU’s AI Act is a good recent example to that effect, whereby the administration pointed out that the proposed law is likely to benefit large companies at the cost of their small and medium-sized counterparts.[111] Instead of advocating overly restrictive, hyper-partisan competition policies, the U.S. government should encourage market-friendly policies — which would help promote innovation and consumer welfare on both sides of the Atlantic.

While the FTC’s success in transatlantic regulatory cooperation has been somewhat limited, it has been more successful in disrupting U.S. trade negotiations. Currently, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and the Department of Commerce are leading trade negotiations for the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF),[112] a U.S.-led trade initiative with 13 member states that account for approximately 40 percent of the global domestic product and 28 percent of international trade in goods and services.[113] However, according to recent reports, the FTC and the DOJ have sought to prevent the USTR and Commerce from successfully tabling the IPEF’s text[114]

Recently negotiated U.S. trade agreements like the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) include boilerplate language related to competition policy.[115] For example, the USMCA text includes, among others, provisions that each signatory state maintain national competition and consumer protection regimes, abide by certain procedures in antitrust investigation and enforcement, and pursue limited cooperation concerning antitrust enforcement against a company from another member state.[116] However, the FTC and the DOJ have objected to the competition policy provisions in the IPEF and insisted the trade agreement reflects certain political goals, leading to delays in the USTR and Commerce Department’s drafting of the IPEF’s text.[117]

As pointed out by Rep. James Comer, the Chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability, the FTC’s recent efforts in trade policy are yet another effort of the agency’s overreach, as it now seeks to influence U.S. digital trade and competition policy and “undermine U.S. business abroad.”[118] Against this backdrop, Congress should ensure that U.S. trade policy does not become yet another avenue through which the FTC seeks to export its political goals overseas. Instead, trade negotiations should primarily be guided by U.S. trade policy objectives and enable the United States to strengthen economic relations while addressing new trade policy challenges.[119] Of course, in an eventual agreement like the IPEF, the FTC might have an essential role in implementing specific data-related provisions.[120] However, to carry out such a role, it is all the more crucial that the FTC regains its reputation as a neutral, impartial regulator that acts within its remit.

Trends in Recent Tech Antitrust Legislation: Insights for U.S. Lawmakers

Against the backdrop of the Federal Trade Commission’s overreach, Congress has an important role in ensuring that the FTC operates within the scope of its mandate. However, as Congress has grown increasingly factious, it has struggled to hold the agency accountable. Instead, some U.S. lawmakers now seek to author poorly designed competition legislation that could introduce unintended consequences in cybersecurity and privacy, among others. If such trends continue, Congress could replace the FTC as the most significant long-term challenge to the traditional U.S. approach to antitrust, as seen in the last few decades.

While a detailed overview of all recent tech antitrust legislation goes beyond this policy brief's purview, a discussion of selected legislation can be particularly helpful for U.S. policymakers. To that end, this section discusses the following legislation: i) the American Innovation and Choice Online Act (S. 2992, H.R. 3816, and S. 2033); ii) the Ending Platform Monopolies Act (H.R. 3825); iii) the Augmenting Compatibility and Competition by Enabling Service Switching Act (H.R. 3849 and S. 2521); iv) the Open App Markets Act (H.R. 7030); v) the Prohibitive Anti-Competitive Mergers Act (S. 3847); vi) the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act (H.R. 3826 and S. 3197); vii) the State Antitrust Enforcement Venue Act (H.R. 3460); and viii) the Merger Filing Fee Modernization Act (H.R. 3843). While these bills are not intended as an exhaustive list of recent antitrust legislation, a discussion of such bills helps understand broader legislative trends and evaluate current and future competition policy proposals.

Classification and Discussion of Antitrust Legislation

In evaluating tech antitrust legislation, it is helpful to distinguish between different types of legislation based on the firms and relevant markets that they seek to cover. To that end, the Congressional Research Service provides a helpful framework for understanding recently proposed antitrust laws.

The first and most common category of recent digital antitrust legislation can be broadly described as “sectoral competition legislation,” for which there appear to be two general subcategories: the designated-platform approach and the market-specific approach. Whereas the designated-platform model applies the same set of rules to covered entities across a range of markets (e.g., e-commerce and social networks), the market-specific approach creates competition rules for specific markets, like app stores and digital advertising.[121]

More specifically, the first sub-category of sectoral competition legislation — or the designated-platform approach — seeks to designate certain online platforms that offer specialized services as “designated platforms” on the basis of several “qualitative and quantitative criteria intended to capture platforms with bottleneck power over business users.”[122] Certain “gatekeeper firms” could be classified as designated platforms if i) they offer “core platform services” (e.g., search engines, online marketplaces, and social networking platforms) and ii) fulfill certain predefined quantitative and qualitative criteria. Several pieces of recent tech antitrust legislation follow this model.[123] One such example is the American Innovation and Choice Online Act, which seeks to regulate vertical integration and self-preferencing by designated platforms. Likewise, under the more restrictive Ending Platform Monopolies Act, covered companies would have been forced to restructure their business model, discontinue vertical ownership of some products and services, and stop offering certain products and services altogether.[124]

The second subcategory of sectoral competition legislation — the market-specific approach — adopts a more targeted strategy than the designated platform model. Instead of mandating the same regulations to covered companies operating in various technology markets, such legislation tends to propose competition rules for specific markets like app stores and digital advertisement.[125] For instance, the Open App Market Act sought to create certain rules for Apple and Google’s app markets, several of which would have exacerbated data security risks while reducing consumer choice.[126] Likewise, although not examined in this report for brevity, the Competition and Transparency in Digital Advertising Act would have mandated structural separation requirements and customer-protection rules for covered digital advertising firms.[127]

Apart from sectoral competition legislation, another type of proposed law seeks to restrict virtually all merger and acquisition activities by dominant technology companies that exceed certain predefined thresholds. Such proposals include the Prohibitive Anti-Competitive Mergers Act and the Trust-Busting for the Twenty-First Century Act.[128] Notwithstanding some differences, the two bills sought to impose blanket restrictions on acquisitions by large technology companies as long as they exceed certain thresholds — without considering the effect of individual transactions on innovation and consumer welfare.[129] Although such bills were ultimately unsuccessful, future legislation along these lines could pose substantial challenges to innovation and consumer welfare.

Lastly, some proposed antitrust laws, such as the State Antitrust Enforcement Act, tend to focus on procedural or financial aspects of antitrust enforcement. Although the U.S. regulatory architecture would benefit from some reform, this legislation’s recommended decentralization of antitrust enforcement would have exacerbated the growing regulatory fragmentation of the U.S. digital economy and increased regulatory uncertainty.

Given different ways of classifying antitrust laws and substantial overlaps between various categories, the taxonomy of tech antitrust legislation is more helpful as a general guideline than as a rigid classification. As the Congressional Research Service reports, the larger body of U.S. competition legislation tends to fall into five categories: “i) ex-ante conduct rules; ii) structural separation and line-of-business restrictions; iii) special merger rules; iv) interoperability and data-portability mandates; and v) changes to general antitrust doctrine.”[130] In practice, recent competition legislation has combined multiple elements of different legislative categories. For example, the AICOA is a classic ex-ante legislation with some interoperability and data-portability requirements.[131] Therefore, instead of treating these groups as mutually exclusive categories, they are more helpful in identifying general characteristics and developing criteria against which new competition legislation can be compared and evaluated.

Selected Recent Technology and Competition Legislation

1. The American Innovation and Choice Online Act (S. 2992 and H.R. 3816 in 117th Congress, S. 2033 in 118th Congress)

The American Innovation and Choice Online Act (AICOA), sponsored by Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA), is arguably the most prominent recent tech-related antitrust legislation.[132] The bill, which was first introduced in the 117th Congress and then reintroduced in the 118th Congress in June 2023, enjoys support from a small and eclectic assortment of Democratic and Republican lawmakers.[133] The AICOA proposes to designate certain technology companies — which exceed certain thresholds for the number of active U.S.-based users, annual sales revenue, and other variables — as “covered platforms.”[134] The proposed law would prohibit the operators of those platforms from ten specific kinds of “self-preference” conduct, that is, activities that privilege the products and services offered by those platforms at the cost of competitor firms.[135] The legislation — which has been criticized as being overly broad and vague — would also provide regulators substantial discretion in deciding who the law would apply to, which activities would be illegal, and what the penalties for such violation should be.[136] In response to wide criticisms, the original legislation was subsequently revised, but the subsequent versions of the legislation remained problematic. Therefore, if passed into law, the AICOA would not only risk dampening technological innovation but also introduce new data security and privacy risks, especially in the absence of comprehensive federal privacy legislation.[137]

First, the AICOA’s overly restrictive provisions would negatively impact consumer welfare — which has been and should remain the cornerstone of U.S. antitrust policy. For instance, the AICOA would target products and services such as Amazon Basics, Google Maps, and Google search results, all of which appear to remain highly popular with consumers.[138] Self-preferencing restrictions would mean that Amazon could not offer its price-competitive “Basics” line of products — unlike the case for retailers such as CVS and Walgreens, which also sell their own lines of products.[139] Likewise, self-preferencing restrictions in the context of search engines would mean, for example, that users searching for stroke symptoms or the nearest hospitals would view less relevant results, including in emergencies. There are instances where specific self-preference activities can be anti-competitive, and these should be addressed through existing legal frameworks. However, the AICOA’s blanket self-preferencing restrictions appear to ignore the question of consumer welfare that has been central to recent U.S. competition policy.

Second, the AICOA’s overly broad and vague language would have accorded too much power to the FTC and the DOJ in defining, interpreting, and enforcing different provisions of the law.[140] Such a move could be especially problematic at a time when the FTC has sought to reshape U.S. competition law without Congressional authorization. Likewise, as Josh Withrow points out, while the DOJ and the FTC would need only a “preponderance of the evidence” to prosecute cases, the burden of proof would fall on companies that they are not causing “material harm” to competitors.[141] This provision not only violates due process by deeming companies guilty unless proven otherwise, but it would also reduce their willingness to offer new innovative products and services for fear of litigation.[142]

At the same time, because of the bill’s overly broad scope, it would have touched virtually all sectors of the digital economy and how companies operate — from search engine results for medical services to spam filters and malware.[143] As the Congressional Research Service notes, many AICOA restrictions mean that the bill would move U.S. antitrust practices beyond the scope of the consumer standard and fundamentally reshape the U.S. competition policy landscape.[144] Recognizing the uncertainty that the proposed law’s overly broad terms would pose to U.S. competition law, the U.S. Bar Association made the highly unusual move of issuing a statement outlining its concerns about the legislation.[145]

Finally, the AICOA would have substantially exacerbated data privacy and security risks because of its interoperability and open-access requirements. As multiple policy experts have noted, the interoperability and open-ended data access requirements mean that there would be few limitations for third-party companies to request and access consumer data from large online platforms.[146] In the absence of a national data privacy framework, such practices could significantly increase risks of data breaches and misuse.[147] That is especially likely when nefarious domestic and foreign actors hide their true identity, disguise themselves as private companies, and mask the purpose of why they seek to access data. Furthermore, overly broad data portability and interoperability requirements — combined with the higher burden of proof on companies — mean that platforms would focus less on ensuring data security and user privacy and more on avoiding legal liability by sharing user data with other companies more freely.[148] As a result, laws like the AICOA risk exacerbating data privacy and security risks at a time when the United States is developing a global reputation as a jurisdiction that cares less about data protection compared to its international counterparts like the European Union and Japan.[149]

2. Ending the Platform Monopolies Act (H.R. 3825, 117th Congress)

While the American Innovation and Choice Online Act would have restricted self-preference activities by designated platforms, some other proposed legislation sought to go further. The Ending Platforms Monopolies Act — introduced by Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and originally cosponsored by Reps. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY), Ken Buck (R-CO) and Lance Gooden (R-TX) — is one such example.[150]

More specifically, the proposed law sought to ban designated entities from selling their own products and services on their platforms.[151] Accordingly, covered entities would have been forced to restructure their business model, discontinue vertical ownership of different businesses, or stop offering certain platform-owned products and services altogether.[152] Beyond the likely discontinuation of Amazon’s Basics line of products, such a law could also impact the operation of many free or low-cost online services, such as Meta’s Facebook Messenger and Alphabet’s YouTube and Google Maps. The reduced availability of such products could ultimately diminish consumer welfare and small businesses that rely on these platforms to sell products and services.[153] However, although the bill cleared the House Judiciary Committee, it was ultimately not introduced in the Senate.[154] Nevertheless, similar future legislation could pose significant challenges to current business models, restricting consumer choice and negatively impacting consumer welfare.

3. Augmenting Compatibility and Competition by Enabling Service Switching (ACCESS) Act of 2021 (H.R. 3849, 117th Congress) and the ACCESS Act of 2023 (S. 2521, 118th Congress)

The ACCESS Act — which sought to promote competition in social media platforms by mandating extensive interoperability and data portability requirements — ranks among the most intrusive recent tech antitrust legislation.[155] Introduced by Reps. Mary Scanlon (D-PA) and Burgess Owens (R-UT), the legislation would have imposed interoperability and data portability requirements for social media platforms and enabled regulators to develop technical standards for their implementations.[156] Although the ACCESS Act failed to become law in the 117th Congress, it was reintroduced in the 118th Congress in July 2023.[157] Due to its overly vague provisions and the granting of substantial legal authority to regulators, its negative impact on data privacy and security could potentially be much larger than under the AICOA and many other policy legislation discussed in this report.[158]

First, the ACCESS Act would grant the FTC too much power in defining technical standards for social media platforms and enforcing them. For example, it would be up to the FTC to define which data would be subject to the ACCESS Act, which interoperability requirements online platforms have to comply with, and how they would implement such requirements.[159] In addition to its rule-making responsibilities, the FTC would supervise compliance with such regulations, and covered companies would have to petition the FTC for approval before making design changes that could affect the platform’s interoperability.[160]

As the Congressional Research Services notes, such requirements could even impact operational decisions like how users send each other “friend requests” on Facebook and other operational requirements for creating interoperability between different social media platforms.[161] These requirements could easily leave the FTC as a de facto overseer of many operational aspects of online platforms and introduce regulatory supervision and surveillance in a way that would be fundamentally at odds with the concept of limited government.

Second, the proposed portability and interoperability requirements would be significantly difficult to implement, especially given the heterogeneity of social media platforms like Facebook, LinkedIn, and TikTok. There are certain contexts, such as transferring a phone number to a new account or email archives to a new email account, where portability and interoperability are desirable and easily implementable. However, in light of the heterogeneous social media landscape, an overly broad portability and interoperability mandate for various data types will be significantly cumbersome and costly, if not virtually impossible in many contexts.[162]

Third, legislation like the ACCESS Act could also create significant future data security and privacy risks. While some jurisdictions, such as the European Union, have sought to create limited data portability rights and interoperability rules, such requirements are often less expansive than would be the case under the ACCESS Act. More importantly, the EU has also created well-developed comprehensive privacy legislation with clear limits on how businesses collect user data and share such information with other platforms.[163]

Without a comprehensive federal privacy law and clear data privacy rules, nefarious actors could easily exploit interoperability requirements. One well-known example of such exploits — as Ms. Caitlin Chin-Rothmann of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) points out — is the Cambridge Analytica scandal.[164] More specifically, Facebook created an application programming interface (API), which allowed developers of one application to access the data of other applications. Cambridge Analytica, a London-headquartered political consulting firm, used this feature to collect and analyze the data of millions of Facebook users without their consent for political profiling and targeting of voters.[165] In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, Meta did not admit to any wrongdoing, but it shut down Facebook’s API features and settled for $725 million, making it the largest U.S. class action data privacy lawsuit at that time.[166] The scandal also paved the way for legislative action worldwide and saw tech platforms limit user tracking and data-sharing with third parties.[167] Without a well-designed federal privacy law, overly broader interoperability and portability requirements could exacerbate the risks that many online platforms and governments have sought to mitigate in recent years.[168]

Lastly, the ACCESS Act would also introduce more surveillance risks. Unlike the case under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, U.S. state privacy laws and sectoral federal states often do not impose significant restrictions on government access to private data.[169] Without such protections against government access to sensitive data, the availability of user-generated data in readable and interoperable format will introduce surveillance risks for American and foreign users of U.S.-based social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

In summary, notwithstanding the best intentions of the ACCESS Act’s co-sponsors, the proposed law and its potential unintended consequences is a case study of how Congress should not write competition and privacy law. U.S. lawmakers should ensure that future technology policy legislation does not introduce significant data protection and government surveillance risks, as would be the case under the ACCESS Act. Finally, given the growing politicization of the FTC and the DOJ and their willingness to act beyond their remit, Congress should be wary of granting such agencies overly broad lawmaking and law enforcement powers. Instead, any future technology and competition legislation should specify clear limits on the powers of regulatory agencies and recommend mechanisms to hold such agencies accountable.

4. Open App Markets Act (H.R. 7030, 117th Congress)

The Open App Markets Act (OAMA) is an example of sectoral competition legislation that adopts a market-specific approach to promote competition in the mobile app markets.[170] The OAMA — which was introduced by Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and included seven Democratic and seven Republican co-sponsors — garnered considerable bipartisan support in its efforts to regulate the mobile app market.[171] Although the OAMA did not target specific companies, its definition of covered company (with more than 50 million U.S. subscribers) meant that both Apple and Google’s app markets would have been subject to the proposed law.[172]

Currently, Apple and Google charge developers between 15 and 30 percent of their subscription fee for offering apps as part of their arrangement with developers.[173] The Open App Markets Act proposed a series of requirements to regulate app markets and reduce Apple and Google’s market shares. Of such requirements, three are particularly noteworthy. First, the OAMA would require that users not be limited to using only in-app stores for purchasing apps. Second, dominant platforms would not be able to take punitive actions against developers for offering subscriptions outside the app store and communicating such offers to consumers. Finally, equal or better pricing should be available in the app store than elsewhere offered by developers.[174]

Although the Open App Markets Act might appear beneficial, its problematic aspects become more evident upon careful evaluation. First, as Dr. Wayne Borough points out, the OAMA’s proposed requirements would have significantly weakened the long-term viability of app stores as a business model — which enables start-ups to develop new apps. Although lawmakers might consider the app store fee a value-added tax for selling subscriptions, the underlying business model is more complex. By participating in Apple and Google’s app stores, developers benefit from a range of tools that help them develop and improve apps by addressing potential design flaws and security concerns.[175]

Furthermore, under the current business model, the most popular apps tend to subsidize the costs of developing novel, innovative apps by new entrants, further contributing to innovation in the app market.[176] In turn, since such applications are tested and vetted through reputable platforms, customers are more willing to take risks and try new apps — which would have been less likely outside a trusted app store environment.[177] Consequently, lawmakers should be wary of policies that could weaken the dynamism of this ecosystem and negatively affect the development of new, innovative apps.

Second, because such a law would require app store platforms to allow the installation of third-party applications (called “sideloading”), it would introduce new security vulnerabilities. That is particularly the case for Apple, which does not allow the download of apps outside the App Store. (In contrast, Google does allow the installation of third-party apps, albeit a warning accompanies such installation.)[178] A major reason behind this approach is Apple’s greater focus on the privacy and security of its iOS ecosystem. According to Apple, although there were 84 million discovered malware attacks, the incidence of successful attacks for Apple’s iOS-operated devices was estimated to be 15 to 47 times fewer than for Android devices.[179] Requiring Apple to allow the side-loading of external applications could easily introduce new vulnerabilities — to the detriment of users who value security and privacy. Ultimately, such a mandate would hamper the ability of companies to develop distinct app ecosystems and harm consumers who would benefit from more diverse choices.[180]

5. Prohibiting Anti-Competitive Mergers Act (PAMA) (S. 3847, 117th Congress)

Whereas proposed legislation like the AICOA and the ACCESS Act are sector-specific competition legislation, some other bills have sought to target tech mergers and acquisition activities more broadly. One such example is the Prohibitive Anticompetitive Mergers Act, which was introduced by Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Representative Mondaire Jones (D-NY). The legislation, which had no Republican co-sponsors, intended to ban certain mergers outright without review.[181]

More specifically, the PAMA would have banned: “i) mergers valued at more than $5 billion, ii) mergers that result in a market share of over 33% for sellers or 25% for employers, and iii) mergers that would result in specified levels of market concentration.”[182] In addition, the bill outlined several changes to the current merger review process. For instance, it recommended extending the HSR waiting period from 30 to 120 days. More worryingly, the PAMA would have allowed regulators to retroactively review mergers completed after January 2000 and to unwind transactions retroactively — if the regulators now viewed those transactions as “prohibited mergers.[183] Due to these overly broad provisions, the proposed law risked dampening technology-related mergers and acquisitions activities and innovation in broad swathes of the U.S. economy.

First, unlike the AICOA or the OAMA, the Prohibitive Anti-Competitive Mergers Act did not focus on regulating specific activities of designated platforms or within specific markets. Instead, the law sought to impose virtually a blanket ban on M&A activities by large technology companies beyond a certain threshold.[184] Such an approach is based on the ideological premise that mergers and acquisitions are, per se, bad for the economy and thus fail to distinguish between anti- and pro-competitive mergers. Consequently, transactions that could increase competitive pressure and promote consumer welfare would be subject to a ban in the same way as transactions that could negatively impact consumers.

Second, defining a “relevant market” — which remains a complicated issue in antitrust enforcement — would have been a significant challenge in the context of the proposed law.[185] For example, a fundamental question that the FTC considered in defining the relevant market for Amazon is whether the market only includes “online superstores” (e.g., Amazon and Target) or whether the definition should be expanded to include other online platforms (e.g., eBay and Etsy) and retail outlets (e.g., H&M and Zara)?[186] Amazon’s market share of all U.S. online retail sales is estimated to be 38 percent; however, this share would decline to around six percent if the definition included all online shopping platforms and retail stores.[187] The way that a market is defined, in turn, affects the share of a specific company within the relevant market.

By allowing regulators to define the relevant market, the PAMA would have exacerbated the problem that some economists call “market fallacy.” Once regulators have made the political decision to sue a firm for anticompetitive conduct, they could define the relevant market in a way that exaggerates a company’s market share and use this definition to block unfavored transactions.[188]

Third, the Prohibiting Anti-Competitive Mergers Act would also have allowed regulators to review transactions and take corrective actions retroactively. Such provisions would not only reduce the international attractiveness and reputation of the U.S. regulatory environment, but they would also raise significant constitutional concerns regarding the prohibition of retroactive laws.[189]

Ultimately, due to the proposed law’s overly partisan nature and its departure from traditional U.S. antitrust thinking, the PAMA did not have a high likelihood of becoming law. Nevertheless, U.S. lawmakers would benefit from taking such legislation seriously for two reasons. First, because of its radical departure from the traditional U.S. antitrust approach, such proposals make legislation like the AICOA appear reasonable by contrast — notwithstanding the latter’s risks to data security and privacy. Second, the PAMA’s overly restrictive approach to antitrust should serve as a reminder of the potential adverse effects of a U.S. departure from the consumer welfare standard. Abandoning an economics-focused, fact-based approach to individual antitrust cases in favor of an overly ideological position could seriously dampen innovation and consumer welfare in the long run.

6. Platform Competition and Opportunity Act (H.R. 3826 and S. 3197, 117th Congress)

Like the Prohibitive Anti-Competitive Mergers Act, the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act (PCOA) is another recent legislation aimed at restricting mergers and acquisitions by tech companies more broadly. Introduced by Representatives Mary Scanlon (D-PA) and Burgess Owens (R-UT), the PCOA sought to prevent covered entities exceeding certain thresholds meeting certain criteria from acquiring current, emerging, and potential competitors.[190] More specifically, the proposed law would apply to companies that have i) at least 50 million U.S.-based monthly users or 100,000 business users and ii) sales revenue or market capitalization higher than $600 billion.[191] For such entities, the legislation would prohibit horizontal mergers, mergers involving “nascent or potential” competitors, and certain vertical mergers that help firms enhance or maintain market positions regarding products and services “offered on or directly related” to an applicable platform.[192] Through such restrictions, the bill’s proponents sought to prevent what its supporters referred to as “killer acquisitions that harm competition and eliminate consumer choice.”[193]

Such an overly broad and vague bill would risk creating significant challenges for U.S. digital innovation and growth. First, as the Congressional Research Service notes, considerable legal uncertainties exist about the definition of mergers that involve “nascent” and “potential” competitors.[194] Such uncertainties would create significant legal challenges and exacerbate uncertainties for large tech companies and start-ups alike — especially if regulators adopt an overly broad definition of who could be considered “competitors” of a covered entity.

Second, the PCOA did not distinguish between anticompetitive mergers and pro-competitive mergers, even though the latter tend to benefit consumers.[195] For example, the bill would have outlawed mergers that help large companies improve the quality of their products and services. That would be the case even if the target company were in a separate industry and did not represent a current, emerging, or potential competitor. Such restrictions would constrain larger technology companies’ ability to become more innovative by acquiring new startups. Instead, they would have to rely on licensing eligible technologies and in-house development for innovation. Consequently, such companies would face difficulties in improving the quality of their product offerings — from displaying more relevant online search results to offering more cost-effective products on shopping platforms. The resulting decline in innovation might benefit the rivals of targeted companies — but not consumers, who would have benefited from improved products and services, irrespective of whether they were offered by larger or smaller companies.[196]

Finally, such an overly restrictive law could weaken the start-up financing ecosystem by dampening the rate of start-up formation and technological innovation. Although some founders might want to scale up their companies, many founders simply want to sell their companies and use the proceeds for new ventures.[197] Even if large technology companies might not purchase a particular start-up, competing interest from tech companies, venture capitals, and other firms could easily drive up start-up valuation and help maintain a more competitive start-up financing ecosystem.[198] Stricter acquisition rules could significantly restrict the ability of companies to acquire new start-ups and weaken the attractiveness of the most popular exit option for prospective start-up founders.

Meanwhile, some legislation, such as the Trust-Busting for the Twenty-First Century Act (S. 1074), sought to introduce even stricter requirements for M&A activities. Whereas an amended version of the PCOA would have set the threshold of exempt transactions at $50 million, S. 1074 would have prevented designated companies from engaging in acquisitions involving deals higher than $1 million.[199] While neither legislation became law, such an extreme approach to M&A transactions remains possible in future legislation. Because of the chilling effect such legislation could have on the start-up ecosystem and digital innovation, U.S. lawmakers should caution against such an overly restrictive antitrust approach.

7. The State Antitrust Enforcement Act (H.R. 3460, 117th Congress)

Beyond antitrust legislation that focus on designated platforms and specific markets or target mergers more broadly, some proposed laws have sought to improve procedural and financing aspects of antitrust enforcement. One such example is the State Antitrust Enforcement Venue Act, which was introduced by Rep. Ken Buck (R-CO) and co-sponsored by Reps. David Cicilline (D-RI), Dan Bishop (R-NC), Burgess Owens (R-UT), and Joe Neguse (D-CO).[200] The legislation, which enjoyed broad bipartisan support, sought to decentralize state-level antitrust efforts. However, several aspects of the proposed law could be harmful, especially in the context of the growing regulatory fragmentation of the U.S. digital economy.