(pdf)

Note: NTUF thanks former Director of Federal Policy Andrew Lautz and former Policy and Government Affairs Manager Will Yepez for their contributions to this paper.

Executive Summary

The Child Tax Credit (CTC), first enacted in 1997, became a much more generous tax benefit to millions of American families in 2021. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) required the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to deliver the CTC – typically a lump-sum benefit delivered once per year in conjunction with a tax return – to parents on an advance, monthly prorated basis, from July through December 2021. ARPA also significantly increased the size of the CTC, from $2,000 per child per year in tax year 2020 to $3,000 per child per year (or $3,600 per child per year aged 0-5) in 2021.

ARPA’s expansion of the CTC, and its requirement for the IRS to deliver CTC benefits monthly, expired with the end of the 2021 tax year. For 2022 through 2025, the CTC is once again a $2,000 per child benefit delivered once per year. Absent further legislative changes, parents will receive their entire CTC benefit when they file their taxes. ARPA also expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for tax year 2021 – but for workers without children. Those changes also expired with the end of the 2021 tax year.

The EITC and the CTC are supposed to help primarily low-income workers (with or without children) and low- and middle-income families with children, respectively. According to U.S. Census data, in 2021 more than 47 million households out of 131 million total households in America (36 percent) reported making less than $50,000 during the year. Of the more than 37 million households with children under 18, 26 percent (9.6 million) reported making less than $50,000 in 2021 and 54 percent (20 million) reported making less than $100,000 in 2021.

The temporary expansion of the CTC and EITC has set off a fierce debate in the halls of Congress, the White House, and in think tanks and policy circles around the nation. Critical questions for policymakers include:

- Should the CTC and EITC be expanded over a longer term?

- Should the CTC transition from a lump-sum benefit at tax filing time to a more frequent, regular payment?

- How can Congress design or reform these credits going forward to be built to last, best supporting families and low-income workers?

- How should lawmakers address some critics’ concerns that significant expansions of these credits may actually disincentivize individuals to work when they are otherwise able?

Some policymakers have proposed one- or two- or four-year extensions of ARPA’s expanded CTC and EITC to mask the full 10-year budget impact of permanent expansion.[1] We see this effort as ‘working the refs’ at the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) who are responsible for scoring the fiscal impacts of proposed legislation. CTC and EITC reforms should be designed (and paid for) with permanency in mind, not just for short-term political benefits with gimmicky budget scores attached.

Some CTC debates have centered on who can recommend the largest credit expansion on a per-child basis, but few have pointed out that the CTC, currently $2,000 per child and proposed to be $3,000 per child under ARPA, was $1,000 per child just four short years ago – and returns to just $1,000 per child in fewer than three years.[2]

We are used to assessing these programs in terms of their multi-billion dollar per-year budget impacts, but improper payment rates in both the CTC and EITC are persistently high. Every dollar that goes to an improper payment could be seen as one fewer dollar to struggling workers or families who most benefit from the program (especially under its refundable provisions).

Both Republicans and Democrats have presided over expansions of the CTC and EITC – and these credits present benefits to taxpayers, including lower overhead and administrative costs for implementation when compared to often complex and bureaucratic government-run programs with reams of rules for beneficiaries and administrators to follow. Less important than one party claiming political victory over the other is making sure that these programs are fiscally sustainable, targeted at the taxpayers who most need support, effectively managed by the federal government, and sensible to the families and workers who must sort through program rules.

This paper presents and analyzes CTC and EITC reform with the following elements:

CTC Reform Recommendations

- Make permanent a $2,000 base credit per child, and add a $400 bonus credit for children ages 0-5. Phase out the credit for single filers making $75,000 per year or more, head-of-household filers making $112,500 per year or more; and joint filers making $150,000 per year or more; the credit would phase out at $50 for each $1,000 in income above these thresholds;

- Allow the refundable portion of the credit to increase with inflation as under current law, meaning that eventually parents will be able to claim the full $2,000 (or $2,400) per child benefit regardless of their income tax liability;

- Allow parents to opt in to quarterly payments of the credit, rather than distributing the CTC as a lump-sum benefit at tax filing time, but require that parents estimate updated income, qualifying children, and filing status when they opt in; and

- Administer the credit through the IRS, but conduct a multi-year study (and possible pilot) on the benefits and drawbacks of the Social Security Administration administering CTC benefits instead.

EITC Reform Recommendations

- Use IRS funding from the Inflation Reduction Act to improve administration of the EITC, in order to better serve taxpayers who may be confused by the complex credit and reduce improper payment rates;

- Consider adjusting the childless worker credit, eliminating the credit for three children or more, and reforming the two-child credit amount to two children or more, to simplify the EITC and to help transition the credit to a work subsidy (rather than a child subsidy);

- Educate EITC claimants on tax preparation options so that they may make more informed choices about the credit;

- Harmonize the definition of a qualifying child between CTC and EITC; and

- Instruct the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA), and others to conduct more studies and more oversight of the program, to reduce improper payment rates and complexity in the future.

Some of these reform recommendations, especially for the CTC, may on their own increase government spending and/or reduce tax revenues. If not offset, our proposals could increase deficits in the short and long run. Therefore, this report includes several pay-for options that Congress could consider when assessing this proposal, including addressing the dependent exemption, reforming the child and dependent care (CDCTC) credit, adjusting CTC phaseout thresholds, extending the state and local tax (SALT) deduction cap, and reducing government spending.

Tax Foundation produced an estimate of the revenue effects of our proposal, with selected pay-for options, and their model found that it is essentially revenue-neutral on a static basis over the 2024 through 2033 window, decreasing revenues by just $10.3 billion over that time period. The proposed extension and expansion of the CTC decreases revenues by $717 billion over the decade, while the elimination of the dependent exemption (+$526 billion), repeal of the child and dependent care credit (CDCTC; +$82.5 billion), and a one-year extension of the SALT cap (+$98 billion) increase revenues by a total of $706.5 billion.

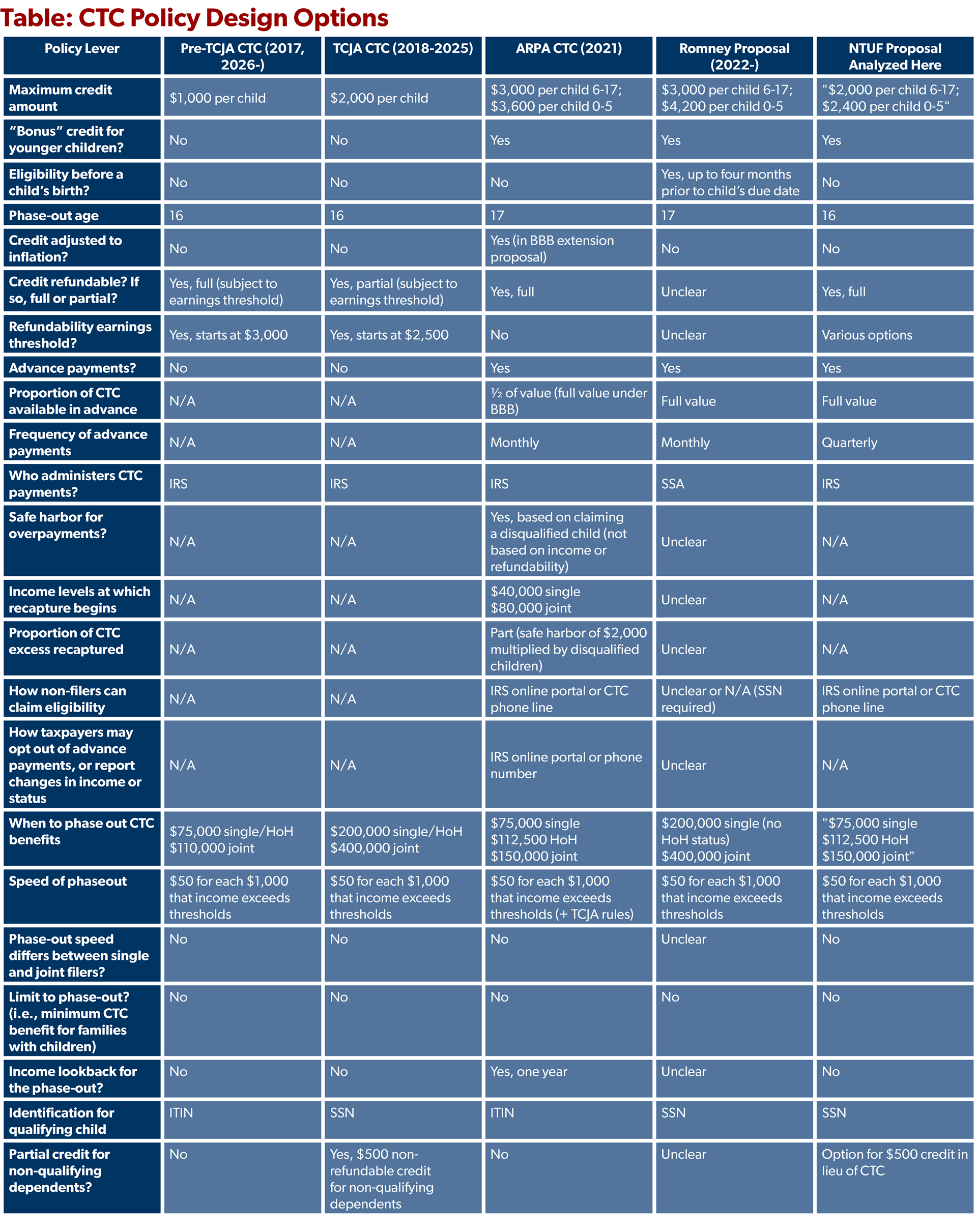

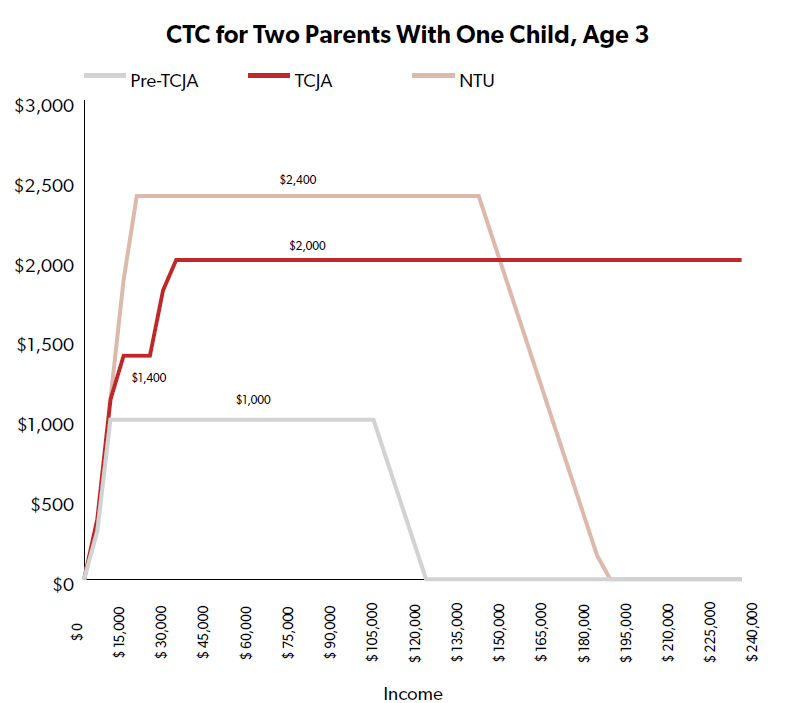

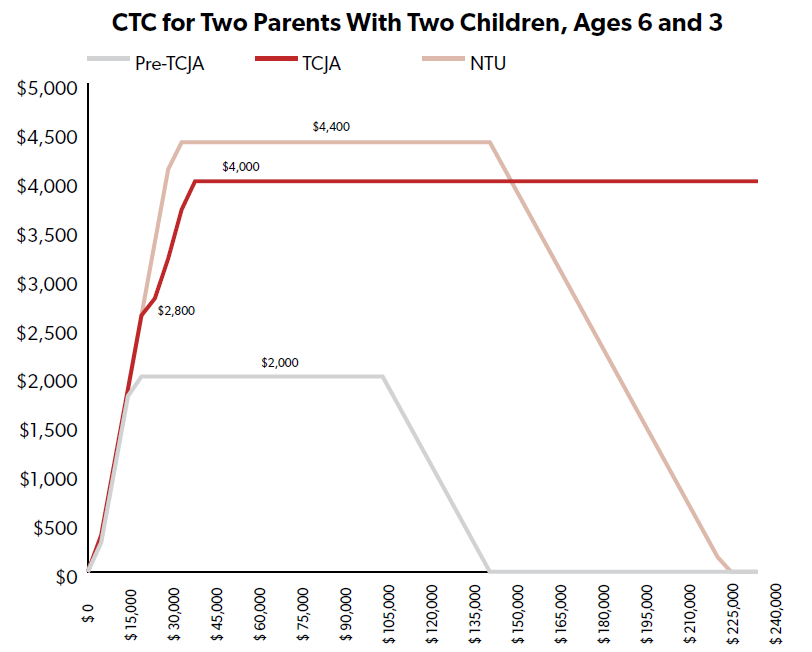

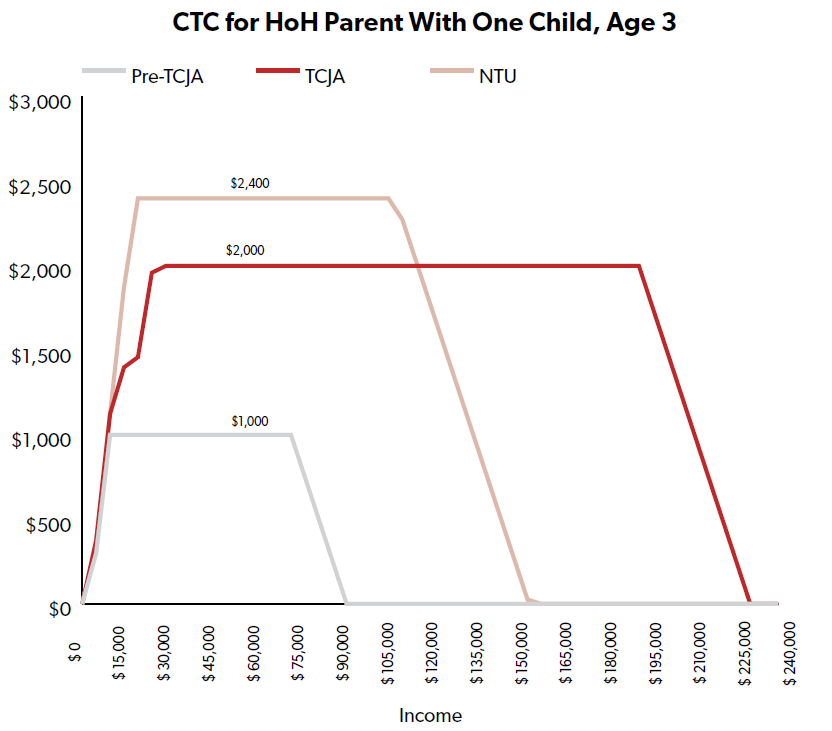

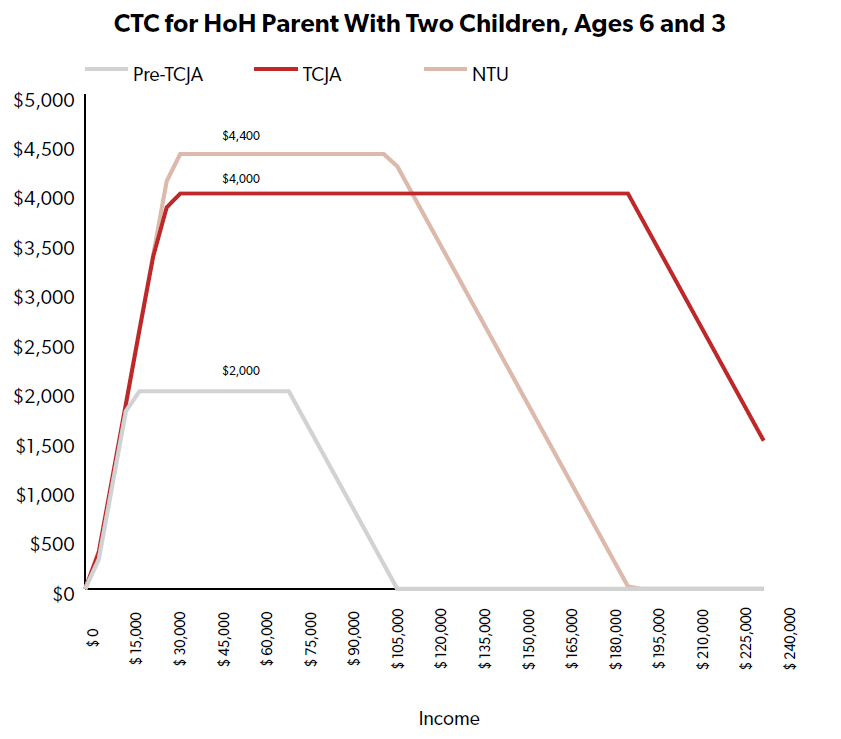

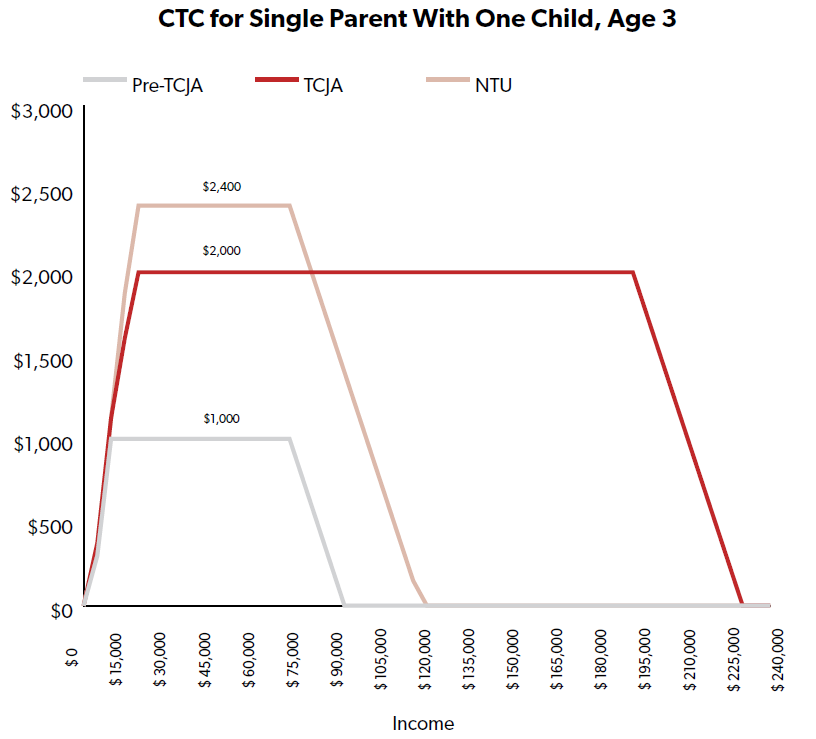

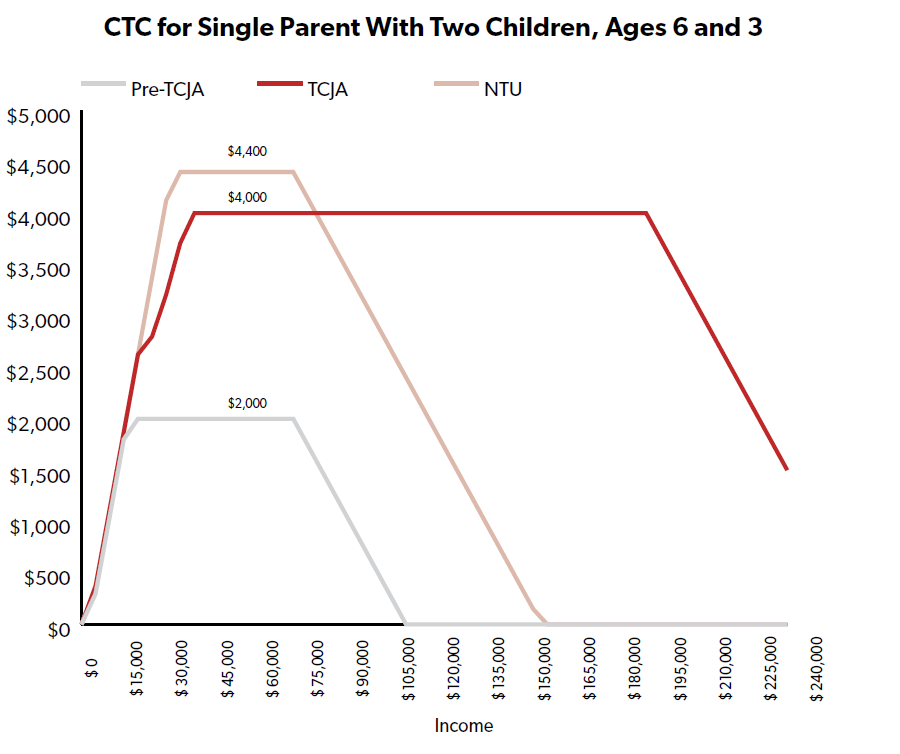

The following charts compare what NTUF’s CTC reform proposal would look like against TCJA’s CTC expansion and the pre-TCJA CTC. We make a few key assumptions in designing these charts: 1) we assume lawmakers keep the $2,500 earnings threshold in order for the NTUF version of the CTC to start kicking in, but we make the $2,400 NTUF CTC option fully refundable; and 2) for purposes of estimating the non-refundable portion of CTC a taxpayer would receive, we assume the taxpayer takes the 2022 standard deduction ($12,950 for single filers, $19,400 for head of household, and $25,900 for joint filers).

Background on the CTC and EITC

Republicans in Congress, center-right policy experts, taxpayer advocates, and fiscal hawks might wonder why a paper outlining a “pro-taxpayer, anti-poverty, and fiscally sound pathway” to an expansion of the CTC, and to reform of the CTC and EITC, is necessary. As of this writing, efforts by the Biden administration and Congressional Democrats to significantly expand the CTC and EITC appear to have stalled, while Congressional Republicans who are generally more skeptical of CTC or EITC expansion control the House of Representatives for a minimum of the next 20 months.

There are at least six compelling reasons, though, why it will become necessary for those in the center, on the center-right, and in fiscally conservative circles to have robust discussions in the months to come about the future of two of the largest and most significant credits in the entire tax code:

- CTC expansion will remain a tax policy priority for Congressional Democrats and President Biden well into the future, and some Congressional Republicans have proposed CTC expansion plans of their own; in other words, the CTC expansion debate is not going away.

- The current CTC expansion space has been dominated by proposals to significantly raise the credit amount compared to Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) levels; specifically, from $2,000 per child to $3,000, $3,600, or even $4,200 per child; up until now, few proposals have attempted to square significant reform efforts (i.e., advance payments, expanded refundability, a bonus credit for young children) with a more fiscally sustainable credit amount (like the one passed in TCJA).

- Even Republicans who support the CTC expansion passed in TCJA will eventually need to grapple with the fiscal impacts of extending the TCJA CTC; the non-partisan CBO estimated in 2022 that even a six-year extension of the TCJA CTC (from tax years 2026 through 2031) would reduce revenues by $500 billion from fiscal years 2026 through 2032.[3]

- A bonus credit for young children could be a more efficient, simple, and fiscally sustainable way to offset the rising costs of child care than the $225 billion President Biden proposed investing in child care subsidies and spending – which, other experts and CBO have pointed out, would increase child care prices while also significantly increasing government subsidies for child care.

- Reform to the CTC and EITC could, if properly designed, reduce the need for more bureaucratic and less efficient, government-run social welfare programs currently in place, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance (SNAP).

- Reform, if properly designed, could also reduce the hours taxpayers spend attempting to comply with the complex rules for the EITC and, to a lesser extent, the CTC.

One question that may remain for readers: why NTUF? Our organization has not engaged in every CTC and EITC reform debate since the 1990s, nor do we work intensely on family policy. We are, however, experts on sound tax policy, fair tax administration, fiscal responsibility and sustainability in the federal budget, and the tax burdens faced by taxpayers.

CTC expansion or reform should put fiscal sustainability, simplicity, and sound tax administration at the center. Some CTC proposals focus on either maximizing the size of the credit – using fiscal gimmicks in the process to suggest such an expansion is ‘paid for’[4] – or on the family policy implications of CTC expansion.

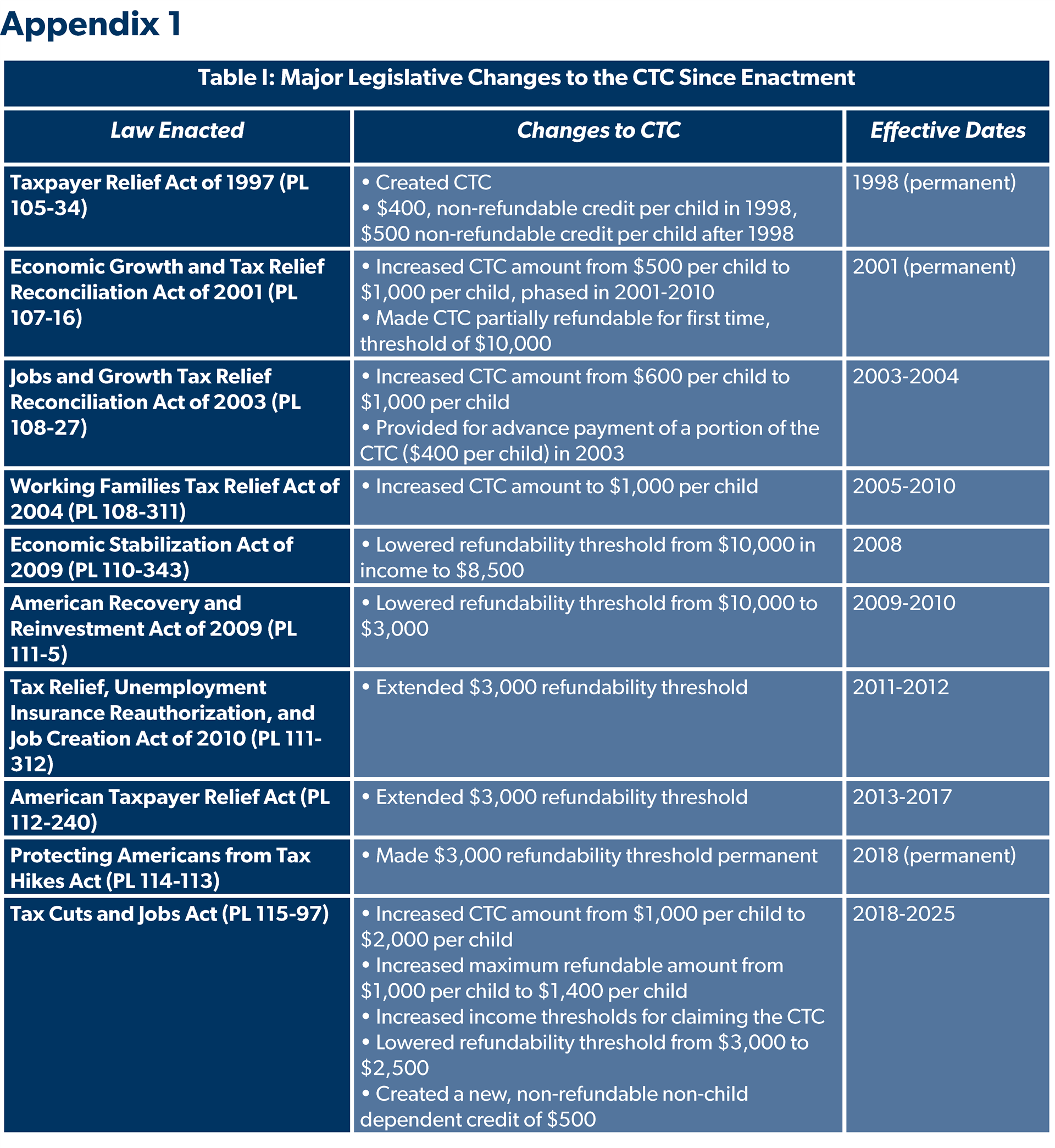

History of the Child Tax Credit. (See Appendix 1 for a complete legislative history of CTC changes.) As detailed by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service (CRS), the CTC was first enacted in 1997 as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act. At the time, the credit was $400 per child in 1998 (almost $725 in 2023 dollars) and $500 per child (more than $875 in 2023 dollars) in the immediate years after that. Refundability of the credit (i.e., whether or not families can receive CTC dollars even after their income tax liability is reduced to $0[5]) was based not on whether or not the family had earned income, as under current law, but instead on family size. Families with three or more children could use an “alternative payroll formula” to receive some CTC dollars as refundable, while families with fewer than three children could only receive a non-refundable CTC.

One goal for the original 1990s-era CTC was to offset the impact inflation had on the value of the personal exemptions a taxpayer could claim for their children on their annual tax filings.[6] As CRS put it:

“Congress indicated that the tax structure at that time did not adequately reflect a family’s reduced ability to pay as family size increased. The decline in the real value of the personal exemption over time was cited as evidence of the tax system’s failure to reflect a family’s ability to pay. Congress further determined that the child tax credit would reduce a family’s tax liabilities, would better recognize the financial responsibilities of child rearing, and would promote family values.”

Three laws passed under President George W. Bush effectively doubled the value of the CTC. In 2001, Congress set out to increase the value of the CTC over time, from $500 per child in 2001 to $1,000 per child in 2010. This 2001 law also made the refundable part of CTC available based on earned income, rather than family size. In 2003, Congress temporarily increased the value of the credit to $1,000, for tax years 2003 and 2004 only (between $1,550 and $1,600 in 2023 dollars). A 2004 law, though, increased the value of the credit to $1,000 through 2010, effectively ending the phase-in first envisioned by the 2001 law.

Under President Obama, several laws effectively lowered the earned income threshold at which the credit would be refundable. The 2009 stimulus package lowered the earnings threshold where a refundable CTC started kicking in from $8,500 to $3,000, not adjusted for inflation.[7] A 2010 law extended both the $1,000 credit (which was scheduled to expire in 2011) and the $3,000 refundability threshold for the 2011 and 2012 tax years only. The 2012 American Taxpayer Relief Act made the $1,000 CTC permanent, and finally the 2015 Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act made the $3,000 refundability threshold permanent.

The one major change to CTC under President Trump came in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which significantly expanded the CTC (and changed CTC rules) temporarily. Under TCJA, from tax years 2018 through 2025, the CTC is doubled in value, from $1,000 to $2,000. The credit is also available to more high-income earners than the pre-TCJA CTC, with the credit beginning to phase out for individuals making $200,000 per year or more and couples making $400,000 per year or more (rather than $75,000 and $150,000, respectively, under pre-TCJA law). Up to 80 percent of the value of the credit (i.e., $1,600 per child) is available as a refundable credit, but there is an earned income requirement to receive the credit.[8] Taxpayers may receive 15 percent of their income above $2,500 as a refundable credit, up to the maximum amount of $1,600 per child. Another major change in TCJA is that, for the first time, children are required to have a Social Security number (SSN) for their parent(s) to receive the credit instead of just a taxpayer identification number (TIN).[9]

In 2021, under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), the CTC was temporarily expanded to $3,000 per child, and $3,600 per child for children ages 0-6. For the first time since 2003,[10] half of the benefit was distributed in regular payments, from July through December 2021, with the IRS sending tens of millions of families monthly checks equal to up to half of the per-child CTC benefit under ARPA. The 2021 law also made the benefit fully refundable for the first time, and had no earned income requirement for full refundability, meaning that parents or guardians with $0 in earned income could receive the full $3,000 (or $3,600) per child benefit. The more generous CTC under ARPA began phasing out at $75,000 in gross income for single filers and $150,000 for couples. ARPA also removed the child SSN requirement for parents obtaining the benefit. All of the ARPA changes were only in effect for tax year 2021.

Congressional Democrats and President Biden have expressed interest in extending the ARPA expansion of CTC. President Biden proposed extending the expanded CTC for four years (2022-25) under his American Families Plan. The House-passed version of the Build Back Better (BBB) proposal would have extended the ARPA version of CTC for one year. The extraordinary budget impact of CTC expansion has affected how long policymakers have proposed extending this more generous CTC.

History of the Earned Income Tax Credit. The EITC is a refundable tax credit available to workers with relatively low incomes. According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), it was first enacted on a temporary basis as part of the Tax Reduction Act of 1975 to encourage economic growth in the face of a recession and rising prices on food and energy. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was concern in Congress about the growing number of families receiving welfare benefits. Legislative proposals focusing on welfare reform surfaced, including the Family Assistance Plan (FAP), proposed by President Richard Nixon in 1971. FAP included a negative income tax (NIT) which would provide a level of guaranteed income even if a taxpayer had zero tax liability. However, the Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee at the time, Sen. Russell Long (D-LA), expressed concerns that the largest benefits of this plan would flow to those without earnings. Sen. Long instead proposed a “work bonus” plan that he believed would encourage workforce participation and offset the impact of the Social Security payroll tax on low-income earners. This work bonus plan was eventually renamed the Earned Income Tax Credit and was targeted primarily to single mothers with children.[11]

Congress’s goals for this tax credit can be found in a 1975 Senate Finance Committee report:

“[T]he committee agrees with the House that this tax reduction bill should provide some relief at this time from the social security tax and the self-employment tax for low income individuals. The committee believes, however, that the most significant objective of the provision should be to assist in encouraging people to obtain employment, reducing the unemployment rate and reducing the welfare rolls. Thus, the provision should be similar in structure and objective to the work bonus credit the committee has reported out previously.”

At the time that Congress created the EITC, the credit was equal to 10 percent of the first $4,000 in earnings, with a maximum credit size of $400 ($2,145 in 2023 dollars), and phased out between $4,000 and $8,000 in earnings. Since its 1975 enactment, the EITC has undergone several changes, including changes in the size of the credit, eligibility criteria, and permanence:

- The Revenue Act of 1978 made the credit permanent, after it had been extended temporarily several times. It also increased the maximum credit amount to $500 (around $2,130 in 2023 dollars) in response to cost-of-living increases, since the original credit had not been indexed to inflation. The credit amount was increased again in 1984 and 1986, primarily to address cost-of-living adjustments and increases in payroll taxes. The 1986 law also permanently tied the credit to inflation going forward. At the end of the 1980s, policymakers began to view the EITC as a well-targeted anti-poverty tool.

- The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 increased the credit and adjusted it for family size. Notably, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 increased the credit and extended the credit to individuals without children. However, around this time, lawmakers were concerned about the costs of the expanded credit and the potential for fraud and abuse. A Government Accountability Office report found significant amounts of the credit were claimed in error. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 denied the credit to any person who improperly claimed the credit in prior years.

- In 2001, policymakers “simplified the calculation of the credit by excluding nontaxable employee compensation from earned income, eliminating the credit reduction due to the alternative minimum tax, and using adjusted gross income rather than modified adjusted gross income for calculating the credit.” In response to a report from the Joint Committee on Taxation that found the structure of the EITC as a primary cause of the marriage penalty among low-income taxpayers, the 2001 law also provided marriage penalty relief by raising the phase-out income level for married couples. Changes in 2009 created a new credit category for three or more eligible children with a 45 percent credit rate and temporarily increased the marriage penalty relief by raising the phase-out level by $5,000 for married couples. The 2001 changes were extended until they were made permanent in 2012, and the 2009 changes were eventually made permanent in 2015.

- The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act (PATH Act), included in the 2015 appropriations package, made changes intended to address improper payments (which include both honest mistakes and fraud). These changes included preventing retroactive claims of the EITC after issuances of Social Security numbers (SSNs). Essentially, “a family issued an SSN in 2017 could not amend their 2016 income tax return and claim the credit on its 2016 return.” Another change required the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to hold income tax refunds until February 15 if the tax return claimed the EITC. Additionally, it required employers to furnish the IRS with W-2s earlier in the filing season. This was intended to provide more time to check income on returns. The IRS reported the most frequent EITC error was incorrectly reporting income, and the largest error in dollars was incorrectly claiming a child.

- In 2021, the American Rescue Plan (ARPA) expanded the benefits of the credit for “childless” workers (those without qualifying children) and reduced the minimum age of eligibility from 25 to 19 for most workers. The childless worker changes included raising the credit rate (phase-in), increasing the maximum credit amount from $543 to $1,502, increasing the income level the credit phases out at, and raising the phase-out rate. These changes were temporary and expired at the end of 2021.

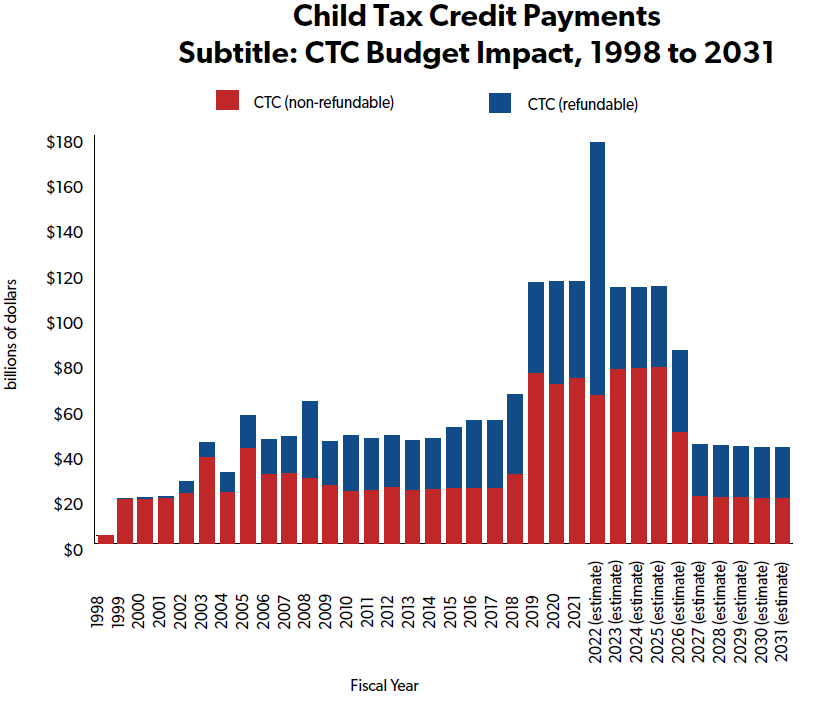

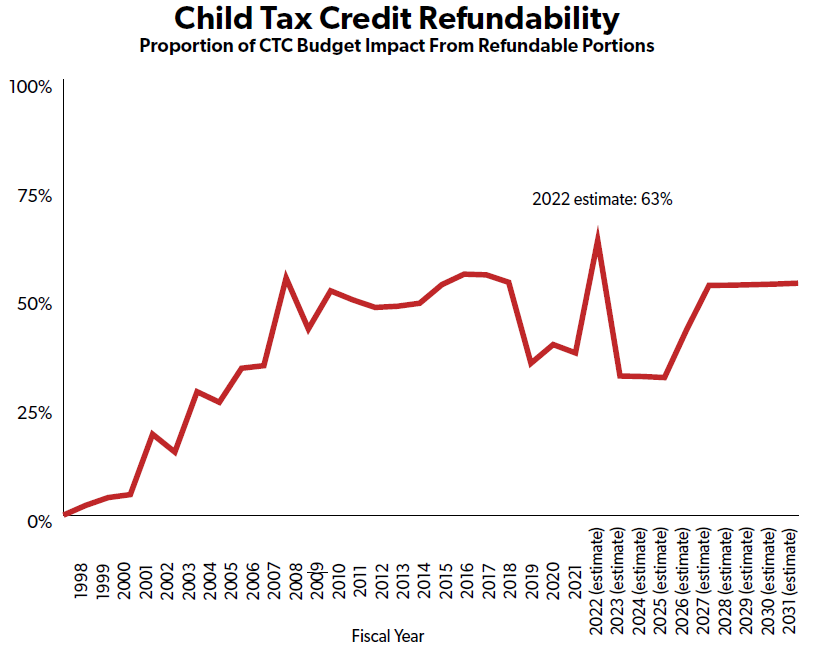

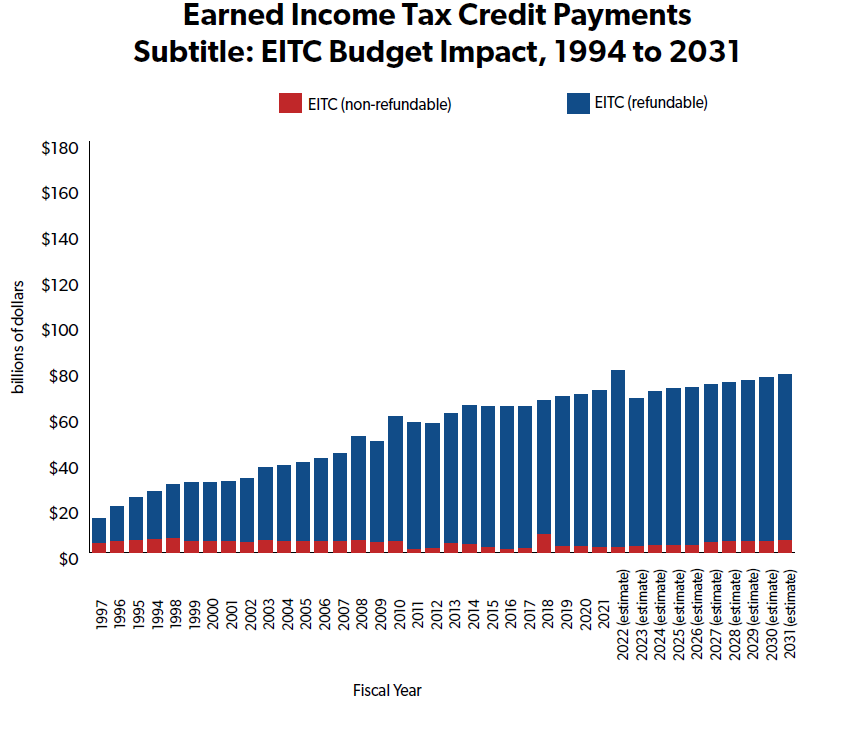

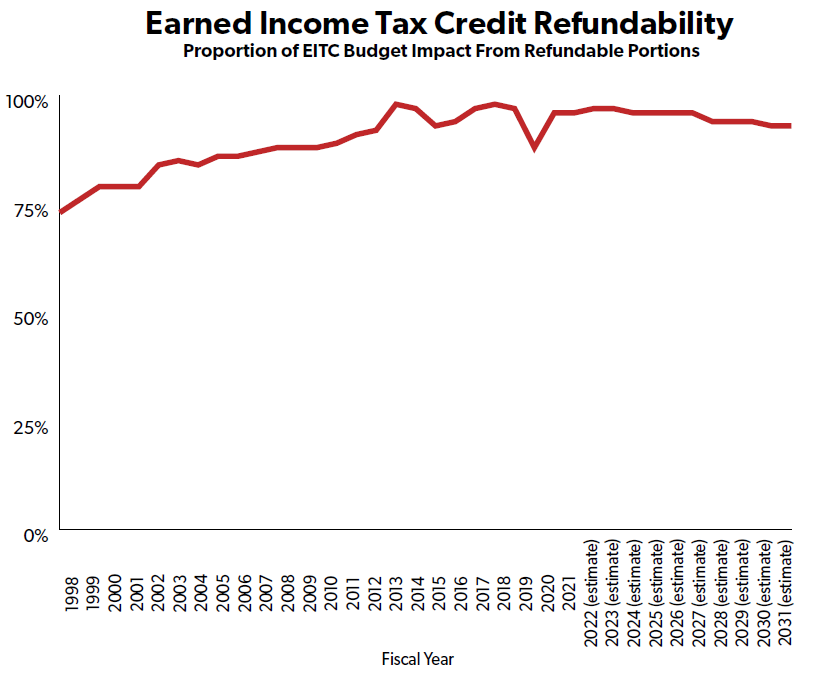

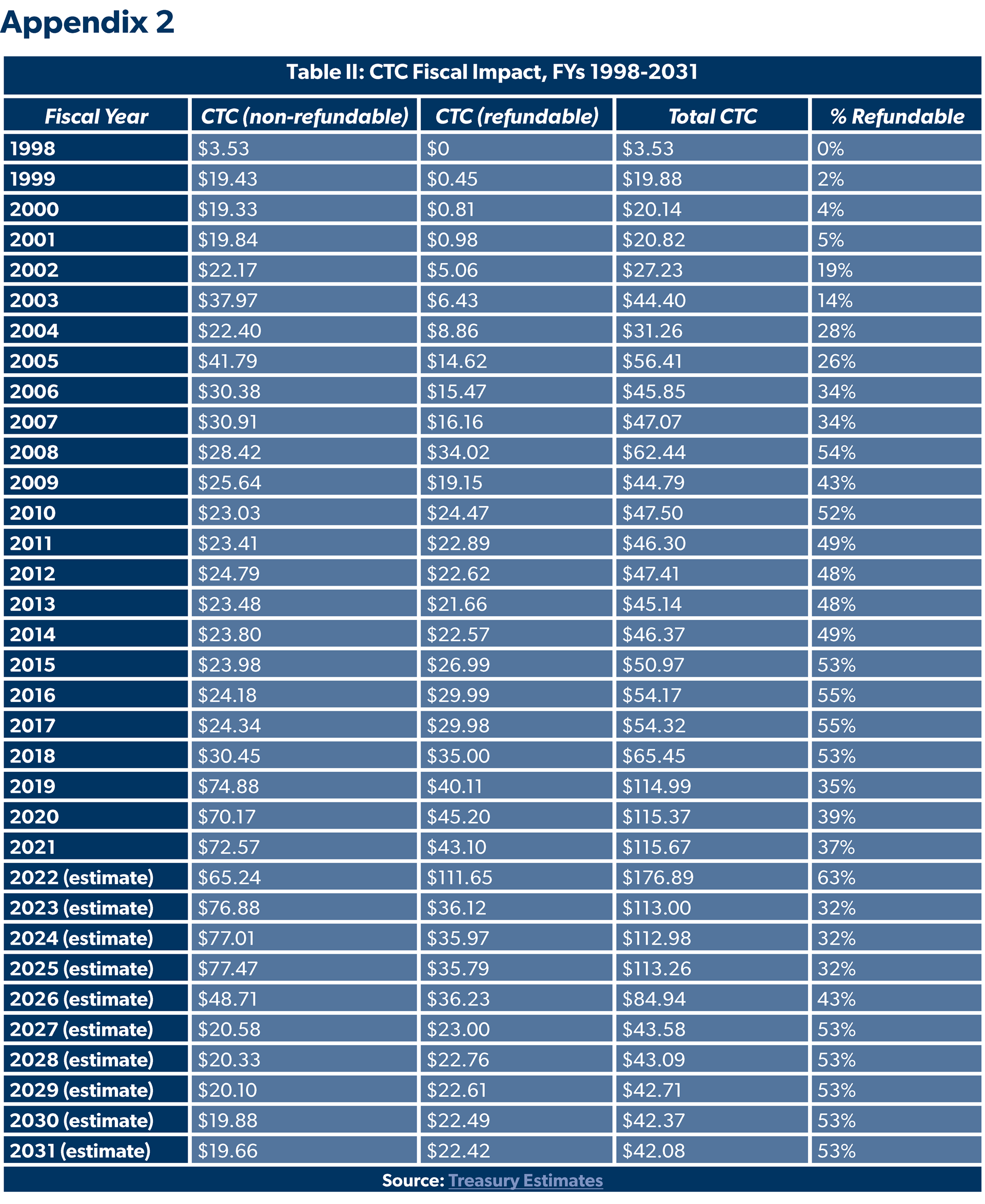

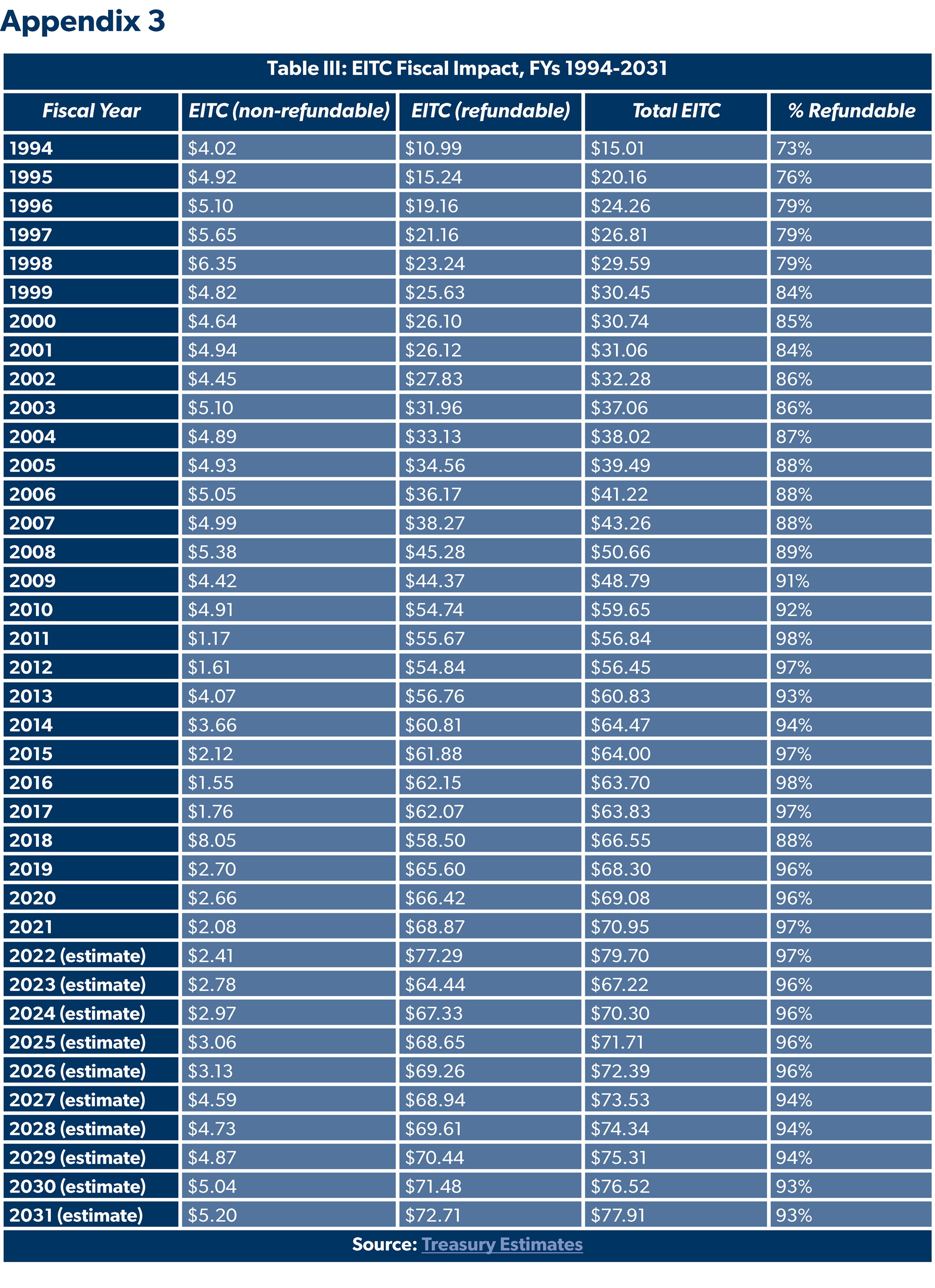

Fiscal Impact. Appendix 2 details the actual and projected fiscal impacts of the CTC from FY 1998 through FY 2031, and Appendix 3 the EITC from FY 1994 through FY 2031, both illustrated in chart form below. Fiscal-year estimates do not line up perfectly with tax-year estimates, since the federal fiscal year runs from October 1 through September 30 while the tax year runs from January 1 through December 31.

Current Problems With the Child Tax Credit

The CTC has enjoyed bipartisan support for decades. There is even bipartisan support for the recent growth in CTC amounts per child, as evidenced by GOP support for a doubling of the CTC in TCJA – and Democratic support for growing the CTC even further in ARPA and Build Back Better Act (BBB).

The CTC is not without its flaws. Unfortunately, hastily written proposals to expand the CTC too often gloss over or, worse yet, ignore these flaws, along with the urgent need to reform both the CTC and the programs that overlap with CTC.

The following is a brief review of the major historical and current issues facing the CTC.

Fiscal Sustainability. The CTC is becoming a more and more expensive program over time. At the national level, the CTC both reduces tax liabilities and increases government spending. The non-refundable portion of the benefit reduces tax revenues collected by the government, because it reduces income tax liabilities for parents. The refundable portion of the benefit increases government spending, because it provides parents with tax credit dollars even after they have $0 in income tax liability.

Combining the non-refundable and refundable portions of the CTC, and the ARPA expansion of CTC had a budget impact of around $180 billion for FY 2022. The TCJA version of CTC had a little more than two-thirds of that annual impact (around $125 billion per year).[12] The CTC before TCJA had a budget impact of only around $50 billion to $55 billion per year in the years leading up to TCJA. Put another way, the CTC’s budget impact almost quadrupled in five years, from FY 2017 to FY 2022.

It is critically important for lawmakers to reduce debt and deficits or, at a minimum, fully offset proposed spending increases whenever possible. It is proper to treat the pre-TCJA CTC as a baseline, so that future expansions are deficit neutral when measured against the average budget impact of the credit before the TCJA expansion from $1,000 per child to $2,000 per child (around $50 billion to $55 billion per year, not adjusted for inflation since FY 2017).

This presents significant challenges. Just making permanent the TCJA-era CTC may have a budget impact of hundreds of billions of dollars in the first decade, whereas the ARPA CTC would have a budget impact of $1.6 trillion over the first decade to sustain on a permanent basis.[13]

Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) contemplated fully offsetting a more generous expansion of CTC in his Family Security Act framework. That proposal would authorize a $3,000 ($250 per month) CTC for parents of children aged 6-17 and a $4,200 ($350 per month) CTC for parents of children under 6. Sen. Romney proposed offsetting this budget impact by eliminating the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, the child and dependent care tax credit (CDCTC), and the head-of-household tax filing status.

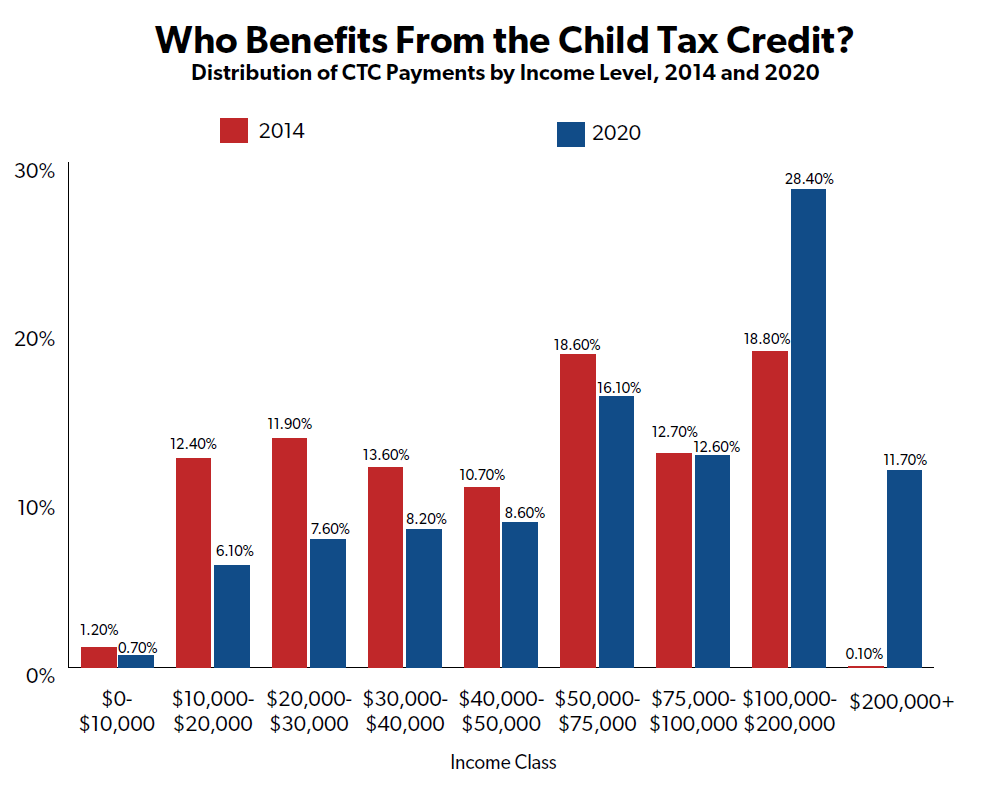

Credit Dollars Flowing to High-Income Families

TCJA expanded the universe of upper-income taxpayers who can claim the CTC, with the phaseout for the $2,000 per child benefit starting at $200,000 in income for single filers and $400,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly. This was a significant increase from the pre-TCJA CTC, which had a phaseout of $75,000 for single filers and $150,000 for joint filers.

American Enterprise Institute’s Kyle Pomerleau has argued that this expansion was included in TCJA in part to “offset the loss of the dependent exemption” that TCJA repealed:

“Prior to the passage of the TCJA in 2017, one way the tax code adjusted tax burdens for household size was with the personal and dependent exemption. The personal exemption allowed households to reduce taxable income by $4,050 per member, but the exemption phased out at $258,250 ($309,900 married filing jointly) in AGI. The TCJA expanded the CTC for households earning up to $200,000 ($400,000 married filing jointly) in AGI to offset the loss of the dependent exemption. This trade helped maintain the adjustment for households with children.”

The expanded CTC, Pomerleau explains, helps ensure the tax code retains some “horizontal equity” – that is, “taxpayers in similar economic situations should face a similar tax burden.” Put another way, the expanded CTC helps ensure that, despite TCJA’s (temporary) repeal of the dependent exemption, policymakers and the tax code still account for the fact that two households making the same income have different expenses if one household has children and the other does not. A dollar of income goes further for a worker who has only herself (or herself and her spouse) to feed, than if she has herself, her spouse, and her child(ren) to feed.

That said, policymakers must grapple with the fact that TCJA significantly skewed the benefits of CTC to households comfortably in the upper middle class. According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), in tax year 2020 more than 40 percent of CTC benefits went to households making $100,000 per year or more. In 2014, only 18.9 percent of CTC benefits went to households making $100,000 per year (less than half their share of the TCJA CTC).

Congress must therefore balance efforts to concentrate the benefits of the CTC more firmly on low-income families, with a narrower CTC eligibility base.

Refundability. One of the most salient aspects of the CTC debate in 2022 has been around the full refundability of the benefit passed by Democrats in ARPA (and proposed by Democrats in BBB), and so-called “work requirements” for CTC. Economists and policy experts have fiercely debated the full refundability of CTC and whether or not policymakers should require work (or, by proxy, earned income) to receive part or all of the benefit. There are at least two separate but related policy decisions to make here: 1) whether or not to make part or all of the CTC refundable, i.e., available even to taxpayers who have no income tax liability, and 2) whether or not to make part or all of the CTC contingent on having earned income.

Regarding refundability, there is bipartisan support for making at least some of the CTC benefit refundable: Democrats prefer to make 100 percent of a $3,000 per child benefit refundable, while Republicans made up to 80 percent of the $2,000 per child TCJA benefit (i.e., $1,600) refundable. There should be a way to bridge this gap.

Work Requirements. During the BBB debate, Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) insisted on work requirements for families receiving the CTC. On one end of the work/earned income debate, experts like the University of Chicago’s Bruce Meyer (and several colleagues) estimate that “weakened work incentives” in the BBB version of CTC “would lead approximately 1.5 million working parents to exit the labor force,” dampening the impact an expanded CTC would have on reducing child poverty.

On the other end of the work/income debate, experts like Foundation for American Innovation's Samuel Hammond (formerly at the Niskanen Center) argue that work or earned income requirements for the CTC are not only unnecessary but actually counterproductive to policymakers’ stated goals for the CTC. Hammond finds that “child allowance” programs in countries similar to the U.S. did not substantially decrease employment rates. He argues that work or income requirements for CTC will increase red tape (bureaucracy) within the CTC benefit, in turn making the benefit more complex and increasing the likelihood of improper payments in the program. Hammond also argues that many zero-income households with children are not “slackers,” but typically are retired grandparents, parents with disabilities, or college students.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) has examined children in families living in poverty,[14] and a few of their findings are relevant to this debate:

- In 2017, 95 percent of U.S. children “lived in families with earned income from work”;[15] in other words, the work debate should affect a relatively small slice of families with children, even accounting for potential work disincentives of an expanded CTC;

- Four million children lived in families with no earnings in 2017; these children are presumably most affected by work requirements for the CTC;

- More than two-thirds of these four million children (2.7 million in total) lived with a single mother or single father, and the vast majority of these 2.7 million children lived with a single mother (2.4 million);

- An additional 600,000 of these four million children lived in families with no parent (i.e., they lived with a grandparent or other guardian), meaning that more than four in five children living in families with no earned income had only one or no parent in the house;

- Some common characteristics of these four in five children are that they lived in families where someone received either disability benefits, retirement benefits, or both.

In other words, many of the children living in families with no income are living with a parent or guardian that is retired, disabled, or a college student.[16]

A separate question is whether a newly expanded CTC will disincentivize work for parents who are already working. American Enterprise Institute (AEI) survey data from October 2021 found that 90 percent of households said CTC payments “[had] not affected my employment (or someone else’s in [my] household).” 5 percent of respondents said the CTC payments helped them work less, while 5 percent of respondents said the CTC payments helped them work more. AEI cautioned that they “would not necessarily expect to see households changing their employment situations due to the new CTC payments in such a short time, mainly because the payments are currently temporary.” Time would tell if the employment effects are consistently a wash under an expanded CTC, but the work requirement question will remain a relevant one in the CTC debate for some time to come.

Design Complexity. CRS notes that the “complexity associated with child-related tax provisions is particularly burdensome for lower-income families.” While the CTC probably has never been as confusing for taxpayers and families as the EITC, several design choices by Congress and the IRS make the CTC a potentially challenging benefit to navigate.

Before ARPA, the refundable portion of the CTC had a phase-in with earned income that lawmakers changed several times during the Obama and Trump administrations.[17] Every version of the CTC, since its passage into law, has included phase-outs that could be confusing to taxpayers in the phase-out range. The ARPA version of CTC actually included two phase-outs, one for the $3,000 per child (or $3,600 per child) benefit, which started at $75,000 in income for single filers and $150,000 for joint filers, and a second phase-out for the $2,000 per child TCJA benefit, which starts at $200,000 in income for single filers and $400,000 for joint filers.

Refundability amounts may be confusing as well. While the pre-TCJA CTC of $1,000 was fully refundable for most taxpayers (subject to an earnings threshold), only a portion of TCJA-era CTC is refundable ($1,600 per child out of the total CTC of $2,000 per child, subject to an earnings threshold). This may confuse some low-income families, who read headlines of a $2,000 per child CTC but only receive $1,600 or less.

And while a majority of families claiming the CTC might have a typical income tax situation (i.e., two parents, married and filing jointly, made up 57 percent of CTC claims in 2019 according to IRS data), many families will not – the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has reported confusion regarding the ARPA version of CTC for separated or divorced parents, and for families with mixed immigration status.

Some of these complexities are hard to avoid. However, policymakers must balance their numerous goals for the CTC and its proposed expansion – reducing childhood poverty, making the benefit fiscally sustainable, avoiding abuse of the program, avoiding widespread work disincentives, and more – with the reality that more complicated benefits contribute to taxpayer confusion, tax administration challenges, and the potential for improper payments.

IRS Administration of Advance Payments. Arguably the most significant CTC reform made by ARPA – even more significant than the increase in the credit value from $2,000 per child to $3,000 per child – was the advance distribution of half the benefit value via monthly payments by the IRS. As other experts have noted, this change brings the ARPA-era CTC closer to a child allowance for parents than a credit claimed once per year at tax filing. The monthly payments may also help reduce child poverty by reducing significant fluctuations in low-income households’ cash flow and reducing the need for those households to go into debt, according to Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

However, policymakers will need to further examine how the IRS performed in distributing monthly CTC payments from July through December 2021.Congress should heed the lessons and recommendations of stakeholders like the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) and adjust CTC advance payment rules accordingly. CRS reported four broad challenges for the IRS in determining advance payment amounts for the CTC:

- A lack of data on eligible households, especially those that do not typically file a tax return;

- The lagged nature of available data, especially when many taxpayers experience significant family changes (e.g., the birth of a new child or a divorce of parents) or significant income changes (e.g., a raise, a new job, or a second job) from year to year;

- Changes in household circumstances, like those mentioned above; and

- Household reconciliation of advance payments, which may hit low-income households particularly hard.

Evidence from other advanced, refundable tax credit programs suggests that overpayment of advance credits, and not underpayment, is the norm. For example, more than half (58 percent) of the households that receive advance premium tax credits under the Affordable Care Act have an overpayment that needs to be paid back (see more below on recapture).

The IRS did run into early challenges administering the CTC monthly payments in 2021, including difficulty navigating the Non-filer Sign-Up Tool on a mobile device, difficulty using the portal for Spanish-language users, the inability of parents to reach an IRS customer service representative through the agency’s CTC phone line,[18] and a general lack of taxpayer knowledge about the importance of using the agency’s CTC portal to update the IRS on changes in family status, income, or size.

More recent TIGTA reporting on IRS performance in delivering the advance CTC indicates a mix of successes and failures, all of which policymakers in Congress should scrutinize and incorporate in any revival of an advance payment option for the CTC:

- On the one hand, the IRS sent correct advance payments to taxpayers roughly 98 percent of the time, according to a September 2022 report;

- One the other hand, roughly 3.3 million payments totaling $1.1 billion were sent to taxpayers “who should not have received the payment,” while a larger 8.3 million payments totaling $3.7 billion that should have been made to “eligible taxpayers” were not made;

- In communicating with tens of millions of taxpayers at the end of 2021 in regards to the advance CTC payments they had received, the IRS got the information correct the vast majority of the time – about 99.99 percent;

- However, the IRS failed to allow taxpayers to update their number of qualifying children or filing status in the online CTC Portal, despite the law requiring them to do so;

- Given more than two million taxpayers used the Portal to unenroll in advance payments, there was clearly an interest among taxpayers in avoiding potential overpayments of the CTC, so any future Portal should immediately provide the ability for taxpayers to update qualifying children and filing status; and

- Unfortunately, TIGTA identified thousands of potential security vulnerabilities with either the Portal or the related Secure Access Digital Identity system that taxpayers could use to access or update information in regards to CTC advance payments.

Given the challenges the IRS faced, there is also an ongoing debate among policymakers over whether to have the IRS or the Social Security Administration (SSA) distribute monthly CTC payments. The IRS has administered the CTC from its creation through the present day, and it distributed the monthly payments of CTC under ARPA. But some policymakers, like Sen. Romney, have argued for SSA to distribute the payments instead. Tax Policy Center’s Elaine Maag has a good summary of this debate:

“Neither SSA nor IRS is the obvious best choice. In the short-term, the IRS holds a slight edge: It has political support and expanding a program is easier than starting a new one. In the long-term, SSA may be better because it has experience delivering monthly payments and shifting benefits when families change. But transitioning from a tax credit delivered by the IRS to a child allowance delivered by SSA might prove difficult and should be done cautiously.”

Would SSA have avoided the hiccups the IRS had in the middle of 2021? It is unclear. If monthly payments are extended in the future, though, Congress must pay close attention to recommendations from GAO, TIGTA, and non-government stakeholders to improve the distribution of monthly payments and uptake of CTC information portals.

Recapture of Overpayments. An additional layer of complexity with the ARPA-era CTC is the recapture of excess advance monthly payments. As noted above, taxpayers’ experience with the ACA’s premium tax credits indicates that a large number of CTC recipients may receive advance monthly payments in excess of what they should receive.

Under ARPA, parents who are provided too much in advance payments are allowed a safe harbor, in effect preventing them from having to pay the IRS back for some of the overpayments – but only if the overpayment was due to “changes in the number of qualifying children” (i.e., a child was eligible for the CTC in 2019 or 2020 but not in 2021). The safe harbor amount is $2,000 multiplied by the number of previously qualifying children who are no longer eligible, and the safe harbor begins to phase out at $40,000 for single filers and $60,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly.[19]

Notably, the safe harbor does not apply for overpayments due to income changes or change in marital status, meaning that taxpayers who receive too many CTC dollars as a result of changes in income during tax year 2021 must pay the whole excess payment back.

It is unclear if Congress will expand the safe harbor with any CTC extension in future legislation, but the recapture matter will be relevant so long as policymakers insist on delivering all or part of the CTC to families on a regular basis.

Improper Payments. While the CTC does not suffer from improper payments at the same scale as the Earned Income Tax Credit (more on that below), the improper payment rate for the refundable portion of the CTC is still unacceptably high.

TIGTA reported in September 2021 that, for FY 2020, the estimated improper payment rate for the refundable portion of the CTC was 12 percent. That means $4.5 billion of refundable CTC dollars were improper payments, or nearly one in every eight dollars disbursed under the program.

Importantly, just because a payment was “improper” does not mean that it was fraudulent. While some improper payments can be due to fraud or abuse of government programs, not all improper payments are fraudulent. Some improper payments are simply due to a federal agency not being able to verify necessary details to ensure that government payments were made to the proper party, at the proper time, and in the proper amount.

Still, high improper payment rates are often an indicator that a government agency is not running a program as efficiently and effectively as it should, and TIGTA has made several recommendations to the IRS to improve their administration of the CTC. One is to give the IRS “correctable error authority to address refundable credit claims with identified income reporting discrepancies.” Another is to make income requirements consistent between the CTC and the EITC.

Current Problems With the Earned Income Tax Credit

Overall, the EITC is a well-targeted anti-poverty tool, with the benefits of the credit heavily concentrated among low-income workers, but it does suffer from some key flaws. This credit is complex for taxpayers to navigate, contributing to a consistently high improper payment rate. There are also questions on how the credit incentivizes workforce participation and the number of hours worked.

Complexity. A taxpayer must meet eight requirements to be eligible for the EITC:

- Have a federal income tax return;

- Have earned income;

- Meet residency requirements;

- Determine if they have qualifying children, based on relationship, residency, and age requirements;

- Be between the ages of 25 and 64 only if there are no qualifying children;

- Have investment income below a certain amount;

- Not be disallowed the credit due to prior fraud or disregard of the rules when previously claiming the EITC; and

- Provide the Social Security number for themselves, their spouse (if married), and any children the credit is claimed for.

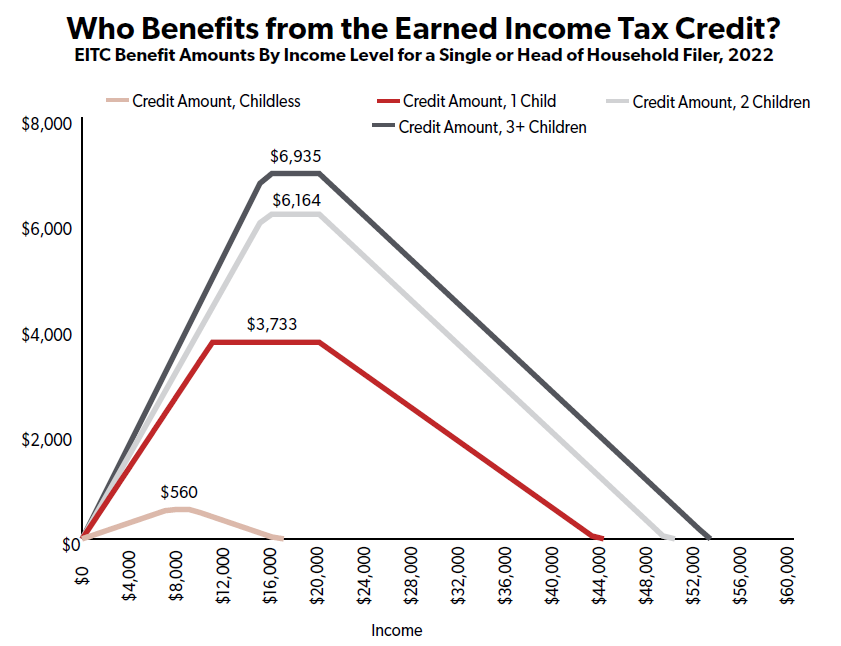

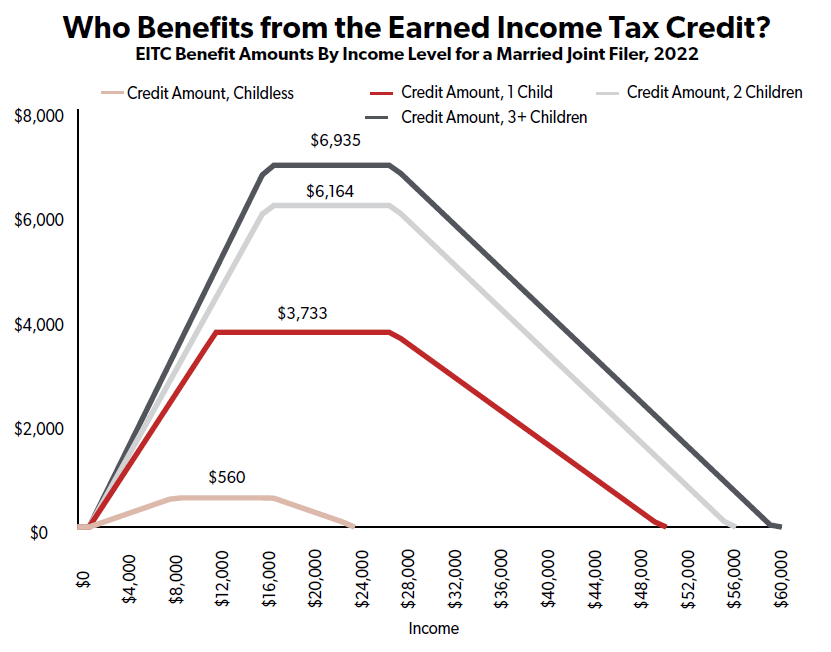

Once these requirements are met, the credit is calculated on the earned income, number of qualifying children, marital status, and adjusted gross income (AGI) of the filer. There is then a “phase-in” range, a “plateau,” and “phase-out” range (see charts). A 44-page guide published by the IRS is meant to assist taxpayers with understanding EITC eligibility requirements and rules.

Improper Payments & Overclaims. The credit’s complexity leads to common mistakes and a high improper payment rate. Improper payments are a fiscal measure of the amount of the credit that is erroneously claimed but not recovered by the IRS. Similarly, overclaims refer to the amount of the credit incorrectly claimed but does not include the impact of enforcement activities. A Treasury Department report states that refundable tax credit overclaims are largely due to statutory design and the complexity taxpayers face when self-certifying eligibility. A CRS report notes the main difference between these two measures is improper payments net out amounts recovered by the IRS, and overclaims do not.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has declared the EITC program a “high-risk program,” meaning that the budget agency has determined the EITC is susceptible to high improper payment rates and, therefore, the IRS must report more robustly and more often on improper payments in the EITC. In FY 2021, the IRS estimated that 28 percent ($19 billion) of the total EITC payments of $68 billion were improper. In the prior five years, the improper payment rate averaged 24 percent. Since 2003, the EITC error rate has not fallen below 23 percent. The credit has the second highest amount of improper payments (in total dollars) in comparison to other government spending programs, behind only Medicaid.

In 2014, the IRS released an EITC compliance study examining the EITC overclaims from 2006 to 2008. This study found the majority of tax filers who overclaim the credit are ineligible for the EITC instead of eligible for a smaller amount. However, this study did not estimate the proportion of errors which were intentional versus honest mistakes made while attempting to comply with complex EITC rules. The three major reasons for errors among claimants, according to the study, were:

- Claiming children who were not qualifying children (largest contributor to overclaimed dollars);

- Misreporting income (most frequent error); and

- Using an incorrect filing status when claiming the credit.

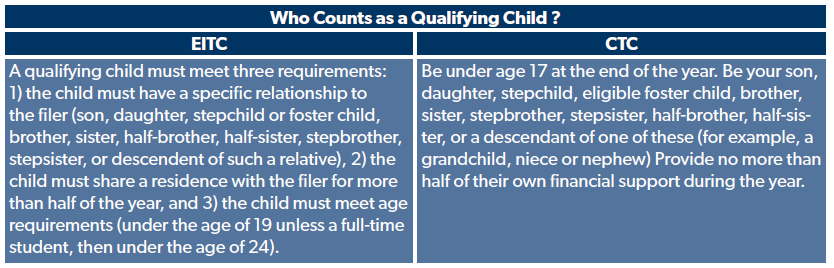

A qualifying child must meet three requirements: 1) the child must have a specific relationship to the filer (son, daughter, stepchild or foster child, brother, sister, half-brother, half-sister, stepbrother, stepsister, or descendent of such a relative), 2) the child must share a residence with the filer for more than half of the year, and 3) the child must meet age requirements (under the age of 19 unless a full-time student, then under the age of 24).

The IRS notes that one of the most common sources of improper payments is when a filer incorrectly claims they have a qualifying child: more than 40 percent of EITC errors pertain to the eligibility of a qualifying child. However, the IRS study from 2006 to 2008 did find the majority of all children claimed for the EITC were claimed correctly (87 percent). Among the 13 percent claimed incorrectly, the residency requirement was the most frequent error (76 percent). The second most common error pertaining to qualifying children was children failing to meet the relationship requirement.

One possible explanation for the high improper payment rate is how the IRS administers the credit. Rather than screening each participant upfront, the EITC relies upon the submission of a filer’s tax return. As the National Taxpayer Advocate office notes:

“Using tax returns as the ‘application’ for EITC benefits rather than a traditional screening process results in low cost with high participation as well as the risk of improper payment. The IRS has pointed out that for the EITC current administration costs are less than 1% of benefits delivered. This is quite different from other non-tax benefits programs in which administrative costs related to determining eligibility can range as high as 20% of program expenditures.”

The IRS also described five barriers to reducing improper payments for refundable tax credits: (1) Complexity of the credit and a lack of data to verify statutory eligibility requirements; (2) A lack of correctable error authority at the IRS (Congress should operate with significant caution here, the agency made mistakes regarding advance CTC errors for the temporary expanded ARPA credit); (3) High turnover of eligible taxpayers from year to year; (4) Unscrupulous and/or incompetent tax return preparers; and (5) Fraud.

In FY 2019, the EITC program accounted for 9.9 percent of all improper payments across government agencies, totaling $17.4 billion. Unfortunately, as a recent Treasury report states, the IRS has made little progress in reducing improper payments in the program.

Marriage Penalty. A marriage penalty occurs in the tax code when a married couple’s net tax liability, after accounting for deductions, exemptions, and tax credits, is larger than if both filers had filed separately. The EITC’s marriage penalty has existed since the credit was enacted in the 1970s, and it occurs due to the structure of the credit, including the phase-out when income rises, and the variation in the size of the credit by number of qualifying children.

A marriage penalty can occur in a number of ways. Two low-income taxpayers who marry may individually both be in the “phase-in” or “plateau” regions of the EITC. However, once married and filing jointly, their combined income could push them into the “phase-out” region, resulting in a smaller credit. For example, in 2018, two single parents claiming one child each, and each with $15,000 in income, would receive $3,461 in EITC each (or $6,922 total), but if they married (with a combined income of $30,000 and two children) their combined EITC would be $2,263 each (or $4,526 total), or 34 percent less.

ARPA temporarily expanded the EITC for workers with no qualifying children for 2021. BBB proposed extending this temporary expansion further for one more year. Aside from the concerns that temporary tax provisions hide costs from taxpayers and complicate the tax code, this change also worsened the marriage penalty. As the Niskanen Center notes, under Democrats’ reconciliation bill, getting married could result in EITC recipients losing access to $2,500 in tax credits per year. Thirty-five Senate Republicans echoed these concerns in a letter to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden.

As a CRS report explains, determining the effect of a marriage penalty on a couple’s decision to marry is challenging due to the number of factors that go into the decision. The research on this topic is inconsistent, but studies typically suggest that the EITC has a modest negative effect or no effect overall on marriage. In NTUF’s view, marriage should not be materially impacted (and certainly should not be penalized) in the tax code.

Impact on Number of Hours Worked. One goal of the EITC was to encourage unmarried mothers to enter the workforce, and studies indicate that the credit has a positive effect on this group’s labor force participation. Additional research from the 1990s found that the EITC reduced new entries into the cash welfare programs. A CRS report states that, based on research around workforce participation and the expansion of the EITC, “many single mothers chose to work, and receive the EITC, rather than apply for welfare.”

A CRS report notes that for married workers, the research is less conclusive. Some evidence suggests that the EITC led a small percentage of mothers to stay out of the workforce, and another study found that legislative changes that expanded the EITC resulted in some married women choosing not to work. However, the report also notes that the more recent research has found the EITC has had a negligible effect on labor force participation for married workers. A GAO report states that the EITC has had a positive effect on labor participation for certain claimants but much less, if any, effect on hours worked.

Of course, most workers don’t consider complex, often competing economic theories as they are making near-term work decisions. While some research points to tax filers taking the size of the credit into consideration when making decisions about the number of hours to work, the impact of the EITC’s design on work incentives is still not conclusive. For example, a study of self-employed workers showed that bunching occurred at the first kink point at the EITC, where the credit is highest. This study points to workers making decisions about the number of hours to work based on the size of the EITC. However, self-employed workers are generally able to exercise greater control over the hours they work than wage workers, and similar bunching did not occur when examining EITC recipients only with wage income.

Policy Options for CTC and EITC Reform

As lawmakers ponder CTC and EITC reform, there are several policy ‘levers’ they can pull on to change these programs. For example, lawmakers could change the credit amounts, or who is eligible for the credits, or what income level the credits phase in and/or out, or any combination of these options and more.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of policy levers for the CTC, followed by reform options for both the CTC and EITC.

These policy levers are only some of the major challenges facing lawmakers in reforming the CTC. Additional challenges include how to handle divorced parents, how to handle legal guardians who are not parents (i.e., grandparents, godparents), how to handle parents or guardians with mixed immigration status; and whether or not to reform potentially overlapping or duplicative programs (e.g., EITC, CDCTC).

For the EITC, as noted in a July 2021 paper, NTUF generally has four principles when it comes to reforming and expanding the CTC:

- Focus the CTC as an anti-child poverty measure, rather than a subsidy for upper-middle class parents;

- Make an extension of the expanded CTC deficit-neutral compared to a pre-TCJA baseline;

- Make anti-poverty programs more efficient for beneficiaries and taxpayers by simplifying and reforming complex and bureaucratic programs in favor of a lump-sum child benefit; and

- Leave low-income households, on net, better off financially than before,[20] with any additional necessary offsets coming from or cuts to wasteful spending throughout the federal budget or highly regressive tax benefits (like SALT).

While balancing these considerations is a difficult act, each of NTUF’s reform proposals below attempts to adhere to one or more of our principles cited above. NTUF proposes the following changes to the CTC, effective from 2024 on[21] (i.e., made permanent unless stated otherwise):

- A $2,000 base credit per child;

- A $400 bonus credit for children ages 0-5;

- Eligibility for the credit starting at birth and through age 16;

- A phaseout of the credit for single filers making $75,000 per year or more, head-of-household filers making $112,500 per year or more; and joint filers making $150,000 per year or more; the credit would phase out at $50 for each $1,000 in income above these thresholds;

- Indexing the refundable portion of the credit to inflation, as enacted under TCJA;[22]

- An income or earnings threshold for the CTC; it was $3,000 before TCJA, $2,500 after TCJA, and $0 (no earnings threshold) under ARPA; NTUF provides a menu of options for policymakers considering how to construct an earnings threshold;

- Allowing parents to opt in to quarterly payments of the credit, rather than receiving the CTC as a lump-sum benefit at tax filing time; and

- Administration by the IRS, paired with a multi-year study (and possible pilot) on the benefits and drawbacks of the Social Security Administration administering CTC benefits instead.

Congress must also ultimately decide whether taxpayers must provide a Social Security Number (SSN) to claim the CTC or just an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN). Undocumented individuals may have an ITIN, but they will not have an SSN. NTUF does not take a position on immigration policy generally.. We assume, for fiscal modeling purposes, that Congress retains the SSN requirement to claim the CTC as passed in TCJA.

CTC: $2,000 Base Credit, with $400 Bonus Credit for Young Children. NTUF’s proposal analyzed here would make permanent the $2,000 per-child per-year base CTC enacted in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), with a new, $400 per-child per-year bonus credit for children ages 0-5.

While President Biden, Congressional Democrats, and some Congressional Republicans (like Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT)) have proposed expanding the CTC to $3,000 per child or even more, estimates from CBO and non-government experts indicate that the permanent budget impacts of a $3,000 per child credit are extraordinary. CBO and the Penn-Wharton Budget Model have both pegged the budget impacts of a permanent, $3,000 CTC at around $1.6 trillion in the first ten years.

Making permanent the $2,000 base credit from TCJA is a much more fiscally sustainable path for Congress, while the $400 bonus for parents with children ages 0-5 would acknowledge and partially offset the higher costs of child care for children ages 0-5.

CTC: Maintaining Eligibility From Birth Through Age 16. Expanding the proposed CTC from 16-year-olds to 17-year-olds, as proposed in BBB, would be a significantly expensive endeavor with a questionable return on taxpayers’ investment. There has yet to be a compelling case from policy experts as to why the CTC should be expanded to 17-year-olds, many of whom have part-time jobs, and some of whom are even in college.

Phase Out the Credit at $75,000 for Single Filers, $112,500 for Head of Household Filers, and $150,000 for Joint Filers. As proposed for the expanded version of CTC under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), the proposed $2,000/$2,400 CTC would phase out at $50 in credits per $1,000 in earned income above the thresholds of $75,000 in modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) for single filers, $112,500 in MAGI for head of household filers, and $150,000 in MAGI for joint filers.[23] The exact level at which the CTC would completely phase out for taxpayers would therefore depend on the number of children they claim a credit for and the age of those children. For example:

- A head of household filer with one child, aged 12, would see the CTC completely phase out at $152,500 in income;

- A head of household filer with one child, aged 3, would see the CTC completely phase out at $160,500 in income;

- A couple jointly filing with two children, aged 15 and 11, would see the CTC completely phase out at $230,000 in income;

- A couple jointly filing with two children, aged 4 and 1, would see the CTC completely phase out at $271,000 in income.

Under both TCJA and pre-TCJA law, the CTC phased out at the same income level for single and head of household filers ($200,000 and $75,000, respectively). However, given the benefits of the pre-TCJA dependent exemption tended to grow with income (making the DE a regressive tax benefit), holding the phaseout threshold at $75,000 for the NTUF CTC expansion proposal – rather than matching the higher, ARPA $112,500 threshold for heads of household – could leave single parents making between $75,000 and $112,500 with higher tax liabilities than they had before TCJA. Our proposal to add a permanent $112,500 phaseout threshold for heads of household is an effort to protect middle-class and upper middle-class single parents from experiencing a significant increase in their tax liability.

CTC: Full Refundability, With a Menu of Options to Address an Income or Earnings Threshold. Although much is made of the debate over “full refundability” for the CTC, this debate often conflates refundability with work/earnings requirements. The latter are controversial; the former, less so.

Congressional Democrats and Republicans are, in theory, not far off on CTC refundability at the moment. Republicans essentially enacted an 80-percent refundable CTC ($1,600 of the $2,000 credit is refundable in 2023), while Democrats have pressed for a fully (i.e., 100-percent) refundable CTC. That gap should be possible to bridge.

Some stakeholders have also raised the point that while a non-refundable CTC can eliminate income tax liabilities for low-income parents, it does not offset payroll tax liabilities that low-income parents accrue when working. Since payroll taxes are applied at a flat rate, kick in at $1 of income, and stop applying to income above a certain threshold, payroll taxes generally make up a higher proportion of low-income taxpayers’ gross income than they do for middle-income taxpayers or high-income taxpayers. A fully refundable CTC could help offset regressive payroll tax liabilities for low-income parents. The NTUF CTC plan achieves full refundability over a long period of time, rather than immediately, by indexing the refundable amount of the CTC to inflation but not indexing the base amount to inflation – essentially a continuation of TCJA policy.

The more politically difficult question is whether or not to have an earnings/income threshold for receiving any CTC benefits. The pre-TCJA threshold was $3,000 in earnings, and TCJA lowered the threshold to $2,500 in earnings. President Biden, Congressional Democrats, and some policy experts want to eliminate the earnings/income threshold, so that parents/guardians with less than $2,500 in earnings (or no earnings at all) can still receive the CTC.

The income threshold applies to earned income, excluding Social Security benefits, pensions, child support, and other non-earnings sources. As noted above, many parents and guardians who report no earnings are either retired, college students, or have a disability that may prevent them from working (or working full-time). Policymakers should explore how to ensure these parents and guardians receive consideration in the tax system for their children, who should not be punished because their guardian is a grandparent or a student or has a disability.

That said, there is bipartisan support for maintaining earnings/income requirements for CTC eligibility. This matter should not completely obstruct broader CTC reforms and expansion. Therefore, we offer a menu of options to policymakers for whom an earnings or income threshold is a non-negotiable requirement for any CTC expansion or extension:

- Policymakers could opt to retain the status quo, TCJA-era $2,500 earned income threshold. This option, in isolation, would increase deficits the least relative to current law, but would also deny CTC dollars to some of the poorest families – many of whom report $0 in income for sensible reasons, such as being a retired caretaker of children, being disabled, or being a student (see above).

- Policymakers could retain the $2,500 income threshold while exempting parents of children ages 0-5. Niskanen’s Sam Hammond (now at the Foundation for American Innovation) and Robert Orr offered similar versions of this proposal in an April 2022 commentary. This option would recognize the disproportionate burden parents face caring for infants and toddlers, but the proposal would add complexity to the CTC benefit.[24] A related concern is how much of the CTC benefit to deliver to parents with less than $2,500 in income. The simplest benefit design would be to deliver the entire, fully refundable benefit to parents of children ages 0-5, essentially eliminating the phase-in for those parents (which affects parents above $2,500 in income as well). The alternative would involve pairing the full (or a partial) delivery of the CTC benefit to parents of children ages 0-5 under the $2,500 threshold, with a retained phase-in for parents above $2,500 in income. However, this would significantly punish parents making $2,501 in income (and those making $3,000, $4,000, $5,000, etc.), lead to some high effective marginal tax rates, and could actually disincentivize work at the margins. This option is fraught with administrative complexity, and policymakers should proceed carefully with benefit design if going down this road.

- Policymakers could retain the $2,500 income threshold while exempting elderly parents/guardians, those with a disability, or parents/guardians who are students. This option would allow those parents and guardians who are least able to work the ability to access the full CTC benefit despite having no or little earnings. However, it may be even more administratively complex than the children ages 0-5 exemption discussed above (for example, the IRS would need to assess disability exemptions), and comes with the same central question above of how much CTC to deliver to exempted parents.

- Policymakers could lower the earnings threshold to $1, so that parents making between $1 and $2,499 can still obtain some portion of the CTC benefit; this helps parents in poverty, including those making more than $2,500 who could benefit from a faster phase-in of the CTC benefit. However, it does not help the millions of parents and guardians who report $0 in income, and are discussed at length above.

- Policymakers could guarantee a portion of the CTC benefit per child regardless of income. Just as 80 percent of the current CTC benefit ($1,600 out of $2,000) is fully refundable, lawmakers could allow a portion of the CTC to be available to parents regardless of income, with the remainder of the benefit phasing in after a $2,500 earnings threshold. The main decision for Congress would be what portion of the CTC benefit should be available regardless of earnings. A $500 amount ($600 for parents of children ages 0-5) would represent a quarter of the NTUF-proposed benefit and matches the $500 non-refundable non-qualifying dependent credit amount Republicans created in TCJA. An $1,000 amount ($1,200 for parents of children ages 0-5) would represent half the NTUF-proposed benefit. A $1,500 ($1,800 for parents of children ages 0-5) would represent 75 percent of the NTUF-proposed benefit, matching the current proportion of the benefit available as fully refundable. The Bipartisan Policy Center has proposed making $1,200 of a $2,200 per-child benefit fully available regardless of earnings.

- Policymakers could convert the $500 TCJA non-refundable non-qualifying dependent credit into a refundable credit with no earnings threshold, and allow parents to choose between the $500 credit or the CTC. This would effectively allow parents a minimum $500 per child benefit regardless of their income. In practice, though, this option could also confuse low-income taxpayers, especially those who would be at the margins for deciding which option would deliver them a greater benefit.

Policymakers could also choose to combine some options; for example, they could convert the non-refundable, non-qualifying dependent credit into a refundable credit with no earnings threshold while lowering the earnings threshold on the CTC to $1.

Some of the above options contribute to further complexity in the CTC. Taxpayer confusion could be mitigated with tax software or ensuring accountants, tax preparers, Volunteer Income Tax Assistance personnel, and Low-Income Taxpayer Clinics (LITCs) are trained to handle CTC questions. Congress could reallocate portions of the Inflation Reduction Act’s $80 billion in appropriations to the IRS for purposes of administering new rules on the CTC and assisting eligible low-income taxpayers in claiming the CTC.

Lawmakers should also recognize that not all parents reporting no or little income are easily capable of working (for a variety of reasons cited above), and should be creative in providing flexibility to parents if retaining some earnings or income threshold becomes a sticking point in negotiations.

CTC: A Quarterly Payment Option, Administered by the IRS. Many of the costs for raising a child occur on a regular and not an annual basis. President Biden, Democratic lawmakers, and some Republican lawmakers (including Sen. Romney) have consequently supported monthly payments of the CTC. Other Republican lawmakers who have been supportive of the CTC, including Sens. Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Mike Lee (R-UT), have critiqued this, arguing that it “destroys the child-support enforcement system, and abandons requirements for work.”

While work requirements for the CTC are a separate matter (discussed above), it is clear that there are some significant concerns with monthly payments of the CTC. There are also practical, logistical complications for a monthly benefit as well, as discovered during the six months the CTC was a monthly benefit under ARPA. These issues include mid-year changes in household size, tax filing status, or income; recapture and reconciliation rules for overpayments; a lag (sometimes multiple years long) in the household and income information for a particular parent/family available to the IRS; and administration of a monthly benefit by an agency (the IRS) that is not very experienced with administering monthly benefits (as opposed to the Social Security Administration).

An option for parents to receive the CTC benefit quarterly would better balance administrative challenges and conservative policy concerns with the reality that parents spend on their children throughout the calendar year and could benefit from a more regular CTC payment.

Under the NTUF proposal, the default option would be for parents to continue to receive the CTC as a lump-sum benefit when they file their taxes, once per year. However, parents could opt in to a quarterly advance payment, at $500 per child for children ages 6-16 and $600 per child for children ages 0-5. For those parents opting in, the IRS would be responsible for four payments, rather than 12 monthly payments under ARPA. Parents choosing the monthly option, likewise, would receive four payments throughout the year, rather than a lump-sum payment at tax filing time under current law. Having a quarterly payment and requiring an opt-in, compared to monthly payments, could also reduce the chances for improper payments of the benefit. For example, if the IRS stands up a successful online CTC portal they could require parents opting in to the quarterly payment to confirm or reconfirm their number of qualifying children, household size, tax filing status, and/or income. Requiring regular updates for parents who opt in to the quarterly benefit should also reduce or eliminate the need for a safe harbor from recapture of CTC overpayments.

Some stakeholders have raised concerns with the IRS’ ability to administer any CTC payments issued more than once per year in a timely and efficient manner, and have suggested that the Social Security Administration (SSA) might be better equipped to handle regular CTC payments to millions of American families. We would suggest a study from the GAO, and potentially a multi-year pilot program where a small sample of CTC beneficiaries receive their payments from SSA. Congress could then assess the results of such a study (and/or pilot program) and determine if SSA is better equipped to manage an expanded CTC in the long term. A reconstituted and revitalized IRS Oversight Board could assist GAO in such a study – at least so far as it pertains to the suitability of the IRS to continue administering a reformed CTC – should Congress decide to engage in such a revitalization effort as NTUF has recommended.

Congress could ensure the IRS budget includes an adequate amount dedicated to ensuring proper and effective administration of mid-year changes that could affect taxpayers receiving advance payments of the CTC, and could consider reallocating some funding from the IRA’s $80 billion in appropriations to the IRS. ARPA did appropriate nearly $400 million to the IRS for administering the advance CTC for 18 months (through September 30, 2022) but this included one-time start-up costs for the IRS to build the online portal for parents reporting mid-year changes to the agency. Lawmakers should ensure any enhanced IRS funding here is limited to administration of the CTC only.

Congress could also direct the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to report annually on IRS administration of an extended, expanded, and advanceable CTC benefit.

CTC: Maintain the SSN Requirement for Claiming the CTC. After the passage of TCJA in 2017, taxpayers claiming the CTC are now required to file a Social Security number (SSN) for the qualifying child. This requirement excludes children who may be unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S. and, as a result, do not have SSNs.

In 2011, TIGTA reported that “[i]ndividuals who are not authorized to work in the United States received [$4.2 billion] from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) [in 2010] in a refundable tax credit based on earned income called the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC).” At the time, TIGTA recommended “the IRS work with the Department of the Treasury to seek clarification on whether or not refundable tax credits may be paid to individuals who are not authorized to work in the United States.” Similarly, in 2012 the National Taxpayer Advocate recommended that Congress “consolidate and modify the EITC with the refundable portion of the CTC into a Worker Credit,” and require an SSN to claim that credit.

For purposes of this paper and for modeling the impacts of our CTC proposals, NTUF assumes that Congress retains the SSN requirement to claim the CTC.

EITC: Consider Adjusting Credit Size and Reducing Overlap. The most straightforward way to reduce complexity and overlap between the CTC and EITC would be to make the former a family-based credit and the latter a work-incentive program. This would reduce some of the complexity of the programs and reduce duplicative benefits, providing relief to taxpayers most in need and modestly reducing the overlap of the programs.

Lawmakers should evaluate the fiscal feasibility of an EITC increase for childless workers. ARPA raised the maximum credit size for childless workers from $538 to $1,502. While nearly tripling the size of this credit without offsets is not a fiscally responsible approach, lawmakers should evaluate a reasonable increase in the childless worker credit size, along with a change to the phase-in and phase-out rates. Childless workers in 2018 received a total of three percent of EITC dollars but accounted for 26 percent of EITC recipients. The average credit size in this same period was $302, while the average size of the credit for a worker with one qualifying child was $2,396.

Additionally, lawmakers should also look at adjusting the size of the credit for married couples to address the marriage penalty. The maximum credit size for married and unmarried filers is $538, meaning two childless workers who marry may incur greater tax liability by filing together. Congress should look to address this issue to ensure taxpayers who choose to marry are not penalized through the tax code.

Another reform Congress can consider to reduce overlap with the CTC and to simplify the EITC is to remove the three or more qualifying children category from the credit. With a more generous CTC outlined above, taxpayers should not be left worse off. While the filers with three or more qualifying children make up the smallest number of filers (3.3 million in 2018), it accounts for the largest average credit amount at $4,311.

As currently structured, a filer receives different levels of benefits depending on the number of qualifying children. The difference between the maximum childless benefit and one qualifying child is $3,046 while the additional benefit in credit size between two qualifying children and three qualifying children is $740. If the size of the credit is intended to represent the cost of raising a child for a worker, the increased amount for additional children should be more uniform to reflect additional costs. Instead, there is a large gap in credit size between childless workers and workers with one qualifying child, and a substantially smaller gap between filers with two children and those with three or more.

Lawmakers could restructure the credit so the categories for a filer are: no qualifying child(ren), one qualifying child, and two or more qualifying children. This would reduce some complexity and hopefully create a more fiscally sustainable tax credit. Again, reforming the CTC to be a family-based tax credit and the EITC to be a work-based tax credit would be the better alternative, similar to Senator Mitt Romney’s (R-UT) Family Security Act. Given such a major change will require careful thought and analysis though, the smaller reforms outlined above could bring some positive fiscal changes to the EITC and still take a meaningful step to reduce program overlap and complexity.

EITC: Expanded Education on How to Claim the Earned Income Tax Credit. A CRS report cites a 2014 study that found that unenrolled tax preparers are both the most common preparers of EITC returns and among the most prone to erroneous claims of the credit. Grassroots education efforts on how tax filers can choose an adequate tax preparer could be beneficial. This would empower tax filers with more knowledge on which type of preparer is best suited for their needs and budget. Tax filers should be better-informed, but still free to choose the best tax preparation option for themselves and their families. Rather than look to impose burdensome licensing requirements on filers, a better alternative would be to expand access to volunteer programs like VITA which appear to have some success in helping address the issue of overclaims on returns.