(pdf)

Under the leadership of Robert Lighthizer, President Trump’s Trade Representative, U.S. tariffs doubled, reducing economic benefits from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and weakening the economy heading into the 2020 elections.1 Now he’s back, calling for massive hikes in import taxes of up to $701 billion a year.2

In 1776, economist Adam Smith explained: “In every country it always is and must be the interest of the great body of the people to buy whatever they want of those who sell it cheapest. The proposition is so very manifest that it seems ridiculous to take any pains to prove it.” But here I go again:

Mercantilism is not “new thinking”

According to Amb. Lighthizer: “Policymakers, business leaders, economists — and the public, most of all — need to abandon the dogma of trade from 18th-century philosophers of the political economy, and embrace new thinking for novel circumstances.”

The new thinking he calls for is nothing more than a return to mercantilism — the idea that exports are good and imports are bad, a theory that dates back to the 1500s. He views trade deficits as a drain on the economy and proposes to eliminate them by imposing big tariff increases to reduce imports.

His belief that trade deficits are bad was completely discredited in the 1700s by economists like Adam Smith: “Nothing, however, can be more absurd than this whole doctrine of the balance of trade, upon which, not only these restraints, but almost all the other regulations of commerce are founded.” Today, most economists would agree with this conclusion from a Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas analysis: “Trade deficits and surpluses are part of the efficient allocation of economic resources and international risk-sharing that is critical to the long-run health of the world economy. Neither one, by itself, is a better indicator of long-run economic growth than the other.”[4]

The Initiative on Global Markets asked a panel of economic experts to respond to this proposition: “A typical country can increase its citizens’ welfare by enacting policies that would increase its trade surplus (or decrease its trade deficit).”[5] Just 5 percent agreed. Chicago Booth economist Anil Kashyap added: “To see the fallacy in this, note that banning imports would crush welfare.”

Amb. Lighthizer calls for a new 10 percent across-the-board tariff to reduce the trade deficit, increasing to as much as 30 percent if the deficit fails to fall. A tax increase of this size would cost taxpayers between $234 billion and $701 billion a year based on 2020 imports of $2.3 trillion. It would make tariffs the third-largest source of federal tax revenue, behind payroll and income taxes. Increasing tariffs is certainly not “novel thinking.” It is more of a throwback to the 1800s, when the federal government relied on tariffs as its main source of revenue.

The last tariff increase of this magnitude was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which increased tariffs by 22.7 percent. Economists and historians generally agree that the Smoot-Hawley tariff exacerbated the Great Depression.

The danger is not that Amb. Lighthizer’s tariff plan won’t reduce the trade deficit. The danger is that it will.

Tariffs typically don’t have much of an impact on trade deficits. A 2019 International Monetary Fund study of 151 countries over 51 years concluded: “We find that tariff increases lead, in the medium term, to economically and statistically significant declines in domestic output and productivity. Tariff increases also result in more unemployment, higher inequality, and real exchange rate appreciation, but only small effects on the trade balance.” (emphasis added)

The danger is that in this case, massive new tariffs would reduce the trade deficit by igniting a trade war and tanking the U.S. economy. There is historical precedent for this outcome. During the Great Recession, imports plunged, and the trade deficit shrank by 45 percent.

The worst-case scenario would be for Lighthizer’s tariffs to trigger an economic depression leading to a decrease in the trade deficit or even the creation of a trade surplus. The United States ran a merchandise trade surplus for most of the Great Depression, for example. U.S. trade policy ever since then has sought to prevent history from repeating.

A trade deficit does not necessarily represent debt to foreigners

According to Amb. Lighthizer: “One country has become a great, persistent trade debtor…. The country has literally handed over trillions of dollars of its wealth to other countries, with China getting the lion’s share.”

But a trade deficit is not a bill that Americans owe other countries. This concept can be confusing because the use of “deficit” in trade policy differs from the way most people use the word.

Suppose you pay $25,000 cash for a new car. Using international trade jargon, you would have a $25,000 deficit with the car dealer. But how much do you owe the car dealer? Nothing. You already paid for the car.

The same goes for international transactions. If you bought your $25,000 car from Germany, the U.S. trade deficit increased by $25,000. This does not in any way mean you (or “America”) owe Germany $25,000.

Here is the only thing that really matters: You are better off because you valued the car more than you valued your $25,000, and the German carmaker is better off because they valued your $25,000 more than the car. Your purchase increases the trade deficit by $25,000, but it is not a $25,000 loss for the United States. It is a win-win transaction.

And if someone accuses you of handing over American wealth to Germany, they are ignoring the fact that Germany can use those dollars to buy U.S. exports or to invest in our economy.

Foreign investment is a benefit, not a cost

Amb. Lighthizer sees foreign investment as a cost of trade, at one point even referring to “negative net foreign investment that resulted from trade deficits.” This is backwards — the United States has a trade deficit because we are one of the best places in the world to invest and because foreign investment fills the gap left by low U.S. savings rates. This results in a trade deficit.

Economist Anne Krueger summed things up: “Of all the topics about trade that appear in the news, there is virtually complete consensus among economists about trade deficits. Trade deficits are not the result of other countries’ tariffs. They are the outcome of a country’s domestic macroeconomic monetary and fiscal policies.”[6]

Moreover, Amb. Lighthizer’s distinction between foreign purchases of U.S. exports (good) and foreign investment in the United States (bad) is arbitrary and meaningless. Consider U.S. economic transactions in 2020, for example.

Americans imported $2.8 trillion in goods and services.[7] Foreigners used most of the dollars they earned to buy U.S. exports, but they also spent $858 billion on U.S. corporate stocks and bonds. These dollars enabled these businesses to make productive investments, the key to economic growth and higher pay for American workers, while boosting the value of Americans’ 401(k) funds.[8]

Foreigners also spent $211 billion in direct investment in U.S. facilities. The 8.7 million Americans who owe their jobs to foreign direct investment would be likely to disagree with Amb. Lighthizer about “negative net foreign investment.”

After all, throughout our early history, the United States consistently ran trade deficits. The resulting capital inflows financed America’s railroads and boosted American manufacturing. A Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis report concluded: “The U.S. ran persistent trade deficits for long periods of its history, just as it does today. Yet, trade deficits did not inhibit U.S. development and may have even facilitated industrialization as the country imported capital goods to improve its own manufacturing during this first phase of industrialization.”[9]

President Reagan understood that point:

During the first 100 years of our nation's history, while we were developing from an agricultural colony to the industrial leader of the world, the United States ran a trade deficit. And now, as we're leading a global movement from the industrial age to the information age, we continue to attract investment from around the world.

Now, some people call this debt. By that way of thinking, every time a company sold stock it would be a sign of weakness, and it would be much better to be a company nobody wanted to invest in rather than one everybody wanted to invest in.[10]

In addition, foreigners spent $311 billion on short-term federal treasury bills. Without that investment, the federal government would have had to increase taxes by up to $311 billion or borrow more from domestic investors at higher interest rates.

Sen. John Kennedy (R-LA) stressed this point in a 2018 exchange with Amb. Lighthizer:

Kennedy: “If we buy a bunch of stuff from Japan, those dollars are going to come back, right? Sometimes through foreign direct investment?”

Lighthizer: “Sometimes it's buying our debt.”

Kennedy: “Good thing they do, huh?”

Amb. Lighthizer seems to want to have it both ways: to him, it’s bad when Americans invest in other countries because it costs jobs, and it’s bad when foreigners invest in the United States because it means we are handing over our wealth.[11] Both things can’t be true.

If the problem is government debt, the solution is to reduce borrowing

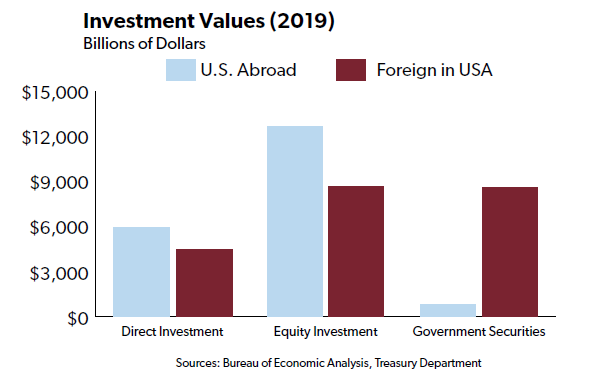

With respect to direct investment like factories and equity investment like shares of stocks, American ownership of foreign assets exceeded foreign ownership of U.S. assets by $2.3 trillion as of 2019.[12] In contrast, foreign ownership of U.S. government securities exceeded American ownership of foreign government securities by $7 trillion.

Figure 1: U.S. and Foreign Investment Values

If someone is legitimately concerned about debt, including China owning $1.1 trillion in treasury securities, the obvious solution is to reduce government borrowing — not to start slapping tariffs on everything.[13]

Investment dollars have the same impact regardless of where they come from from

Amb. Lighthizer cites Warren Buffett, who in 2003 expressed concern about trade deficits and foreign purchases of U.S. assets.[14]

Interestingly, in 2015, Mr. Buffett told global participants in the annual SelectUSA Investment Summit, the highest-profile event dedicated to promoting foreign direct investment in the United States:

“Berkshire-Hathaway’s going to do well in the years ahead but I think we’ll have a lot of people coming from around the world that are going to do very well too…. you’re going to want to come here.”[15]

More recently, he said: “If we actually have a trade war it will be bad for the whole world.”[16]

It makes no difference to a U.S. company seeking funds to build a new hospital whether the money comes from New York City, Omaha, London, Tokyo, or somewhere else. It makes no difference to a U.S. autoworker whether their checks carry the logo of Ford or Toyota. Americans benefit when the United States maintains an economic environment that is favorable to both domestic and foreign investors.

Imports are a sign of a strong American economy

According to Amb. Lighthizer: “The problem is that America is also by far the largest importer in the world.”

America is the largest importer in the world because we are the richest country in the world. That is a blessing, not a problem.

History demonstrates that the surest way to reduce imports would be to make Americans poorer. In tough economic times, Americans have fewer dollars to spend on imports, so the trade deficit tends to decrease and vice-versa. This relationship has been repeatedly confirmed.[17]

International trade and foreign investment are good for workers

Amb. Lighthizer adds: “America’s trade situation has contributed to a hollowing out of manufacturing capabilities, loss of millions of jobs, wealth inequality in the country and damage to the cities and towns that have relied on these jobs.”

Freeing American workers and entrepreneurs to specialize in economic activities in which we have a relative advantage while also allowing Americans to freely import goods from other countries leads to new jobs, higher wages, and a more affordable cost of living.

From 1990 to 2018, encompassing the creation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the WTO, and China’s accession to the WTO, imports increased from 10.6 percent of GDP to 15.3 percent of GDP and the United States ran a trade deficit every single year.[18] At the same time, real U.S. manufacturing output increased by 72 percent, the economy added 36.8 million new jobs, and the lowest quintile of U.S. households saw their average real income increase by 72.1 percent.[19]

Figure 2

While trade deficits don’t matter, government trade policy does. For example, The Heritage Foundation’s annual Index of Economic Freedom compares the trade policies of countries around the world and consistently finds that lower tariff and non-tariff barriers are correlated with increased prosperity.[20]

Friedrich Hayek rejected protectionism

According to Amb. Lighthizer, “Even Friedrich Hayek, Keynes’ adversary in debates over the role of the state in the economy, assumed that trade imbalances would be temporary, not perpetual.”

Talk about missing the point. Here’s what Hayek wrote: “There is perhaps no single factor contributing so much to people’s frequent reluctance to let the market work as their inability to conceive how some necessary balance, between demand and supply, between exports and imports, or the like, will be brought about without deliberate control.”[21]

Hayek was clearly trying to explain that broadly speaking, markets tend to balance over time without government intervention. As economist and CafeHayek proprietor Donald Boudreaux explained: “Hayek was bemoaning the widespread misconception — borne of a failure to grasp basic economics — that an optimal amount of exporting and importing can be achieved only if trade is controlled by government.”[22] The balance between U.S. trade and investment flows illustrates Hayek’s broader point.

Hayek left no doubt about his position on trade policy: “If you have any comprehension of my philosophy at all, you must know that one thing I stand for above all else is free trade throughout the world.”[23]

New tariffs would weaken the United States with regard to China

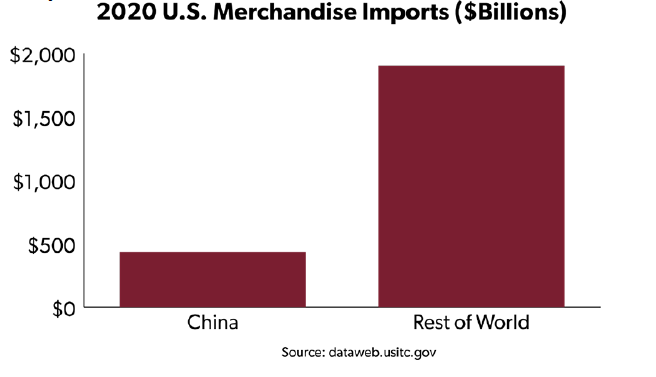

Amb. Lighthizer rightly criticizes communist China’s leadership. However, his proposed across-the-board tariff increase would not primarily apply to imports from China. In fact, it would largely hit U.S. friends and allies, since 81 percent of U.S. merchandise imports come from countries other than China.

Figure 3

During the Cold War, the United States led efforts to reduce trade barriers between friendly nations to counter the USSR.[24] It would be more effective for the United States to follow this strategy instead of indiscriminately increasing tariffs and driving countries into the arms of U.S. rivals. As one example, reinvigorating discussions about joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership (now called the “Comprehensive and Progressive” TPP) would be a step in the right direction as a way to build multilateral trade relationships that strengthen other countries in the region.

Tariffs reduce U.S. leverage and increase the likelihood of conflict

Amb. Lighthizer has said that tariffs provide “leverage” for the United States against our trading partners, a view that U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai has echoed.[25]

In reality, tariffs reduce our leverage with other countries. To name two obvious examples, we have free trade agreements with South Korea and Mexico and maintain trade sanctions against North Korea and Cuba. One would be hard-pressed to find anyone who thinks we have more leverage with North Korea and Cuba than we do with South Korea and Mexico. While those are extreme cases, it’s generally the case that the stronger our commercial ties with other countries, the more influence the United States has.

Tariffs rarely work as a tool to force other countries to accede to U.S. demands. Consider what happened after Amb. Lighthizer and the Trump administration tripled tariffs on imports from China: the country systematically dismantled liberty in Hong Kong, expanded its repression of Uyghurs, increased threats against Taiwan, and ramped up state intervention in the economy.[26] Clearly, tariffs did little to make China more amenable to a friendly relationship with the United States.

Policymakers should be mindful of the historical relationship between trade conflicts and military conflicts, an understanding that has guided U.S. trade policy since the end of World War II. As Cordell Hull, Secretary of State for Franklin Roosevelt, said: “I saw that wars were often caused by economic rivalry. I thereupon came to believe that if we could increase commercial exchanges among nations over lowered trade and tariff barriers and remove international obstacles to trade, we would go a long way toward eliminating war itself."[27]

The country’s leading trade historian, Doug Irwin, observed: “Economists and political scientists have found empirical support for the proposition that trade promotes more democratic political systems, which in turn tend to be more peaceful than other regimes.”[28]

Conclusion

According to Nobel laureate Paul Krugman: “[A]ll of the things that have been painfully learned through a couple of centuries of hard thinking about and careful study of the international economy -- that tradition that reaches back to David Hume’s essay, ‘On the balance of trade’ -- have been swept out of public discourse. Their place has been taken by a glib rhetoric that appeals to those who want to sound sophisticated without engaging in hard thinking.”[29]

Amb. Lighthizer’s views fall into this category, yet they continue to resonate as the Biden administration stumbles down the path he charted as U.S. Trade Representative under President Trump.[30] Unfortunately, Americans will soon be losing three legislators who have the deepest understanding of international trade: Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX), Rep. Ron Kind (D-WI), and Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA). The country will need new advocates in both parties to emerge who will push back against the kinds of destructive policies recommended by Amb. Lighthizer.

RECOMMENDED READING ON TRADE DEFICITS:

Alan S. Blinder, A Brief Introduction to Trade Economics: Why deficits are normal, especially for a country like the U.S.

Daniel Griswold, Plumbing America's Balance of Trade

Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Zhiyao (Lucy) Lu, Macroeconomic Forces Underlying Trade Deficits

Dan Ikenson, The U.S. Trade Deficit Is Not A Debt To Repay

Douglas A. Irwin, Trade Truths Will Outlast Trump: The president’s failed experiments with tariffs and bilateral deals helped validate old best practices.

Daniel B. Klein and Donald J. Boudreaux, The "Trade Deficit": Defective Language, Deficient Thinking

Robert Z. Lawrence, Five Reasons Why the Focus on Trade Deficits Is Misleading

N. Gregory Mankiw, Want to Rev Up the Economy? Don’t Worry About the Trade Deficit

Scott Miller, Don’t use the trade deficit to keep score

Mark J. Perry, Worried about trade deficits? Don’t, they’re ‘job-generating foreign investment surpluses for a better America’

[1] Gleckman, Howard, “For Many Households, Trump’s Tariffs Could Wipe Out The Benefits of the TCJA.” Tax Policy Center, May 14, 2019, and Anderson, Stuart, “Trump’s Tariffs Were Much More Damaging Than Thought,” Forbes, May 20, 2021.

[2] Lighthizer, Robert, “Robert Lighthizer on the need for tariffs to reduce America’s trade deficit.” The Economist, October 5, 2021.

[3] Smith, Adam, “Of the extraordinary Restraints upon the Importation of Goods of almost all Kinds, from those Countries with which the Balance is supposed to be Disadvantageous.” An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776.

[4] Gould, David M., and Roy J. Ruffin, “Trade Deficits: Causes and Consequences.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Economic Review, Fourth Quarter 1996.

[5] Mordfin, Robin I., “Reduce trade deficits, increase welfare?” Chicago Booth Review, December 11, 2014.

[6] Krueger, Anne O., “Do Trade Deficits Matter?” International Trade: What Everyone Needs to Know, October 5, 2020.

[7] U.S.Bureau of Economic Analysis, “International Transactions, International Services, and International Investment Position Tables, Table 1.1: U.S. International Transactions.”

[8] Wilford, Andrew, “What Do Stock Buybacks Mean for the Economy?” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, April 5, 2018.

[9] Reinbold, Brian, and Yi Wen, “How Industrialization Shaped America's Trade Balance.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Regional Economist, February 6, 2020.

[10] Reagan, Ronald, “Remarks and a Question-and-Answer Session With Members of the City Club of Cleveland, Ohio.” The American Presidency Project, January 11, 1988.

[11] Lighthizer, Robert, “The Era of Offshoring U.S. Jobs Is Over.” The New York Times, May 11, 2020.

[12] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Direct Investment by Country and Industry, 2020,” and U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Foreign Residents' Portfolio Holdings of U.S. Securities.”

[13] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities.”

[14] Buffett, Warren E., and Carol J. Loomis, “America's Growing Trade Deficit Is Selling The Nation Out From Under Us. Here's A Way To Fix The Problem--And We Need To Do It Now.” Fortune Magazine, November 10, 2003.

[15] “Warren Buffett explains why foreign investors should consider doing business and operating in the United States.” SelectUSA Investment Summit, March 23, 2015.

[16] Stempel, Jonathan, and Jennifer Ablan, “Warren Buffett says U.S.-China trade war would be 'bad for the whole world.'” Reuters, May 6, 2019.

[17] Griswold, Daniel, “America’s Misunderstood Trade Deficit.” The Cato Institute, July 22, 1998; Scissors, Derek, “The US-China trade deficit, revisited.” American Enterprise Institute, February 8, 2021; Ikenson, Daniel J., “The U.S. Trade Deficit Is Not a Debt to Repay.” The Cato Institute, March 22, 2016; and Riley, Bryan, “2017: Bigger Trade Deficit and an Even Bigger Economy.” National Taxpayers Union, April 19, 2018.

[18] Federal Reserve Bank, “Shares of gross domestic product: Imports of goods and services.”

[19] Author’s calculations from Federal Reserve Bank, “Industrial Production: Manufacturing,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey,” and Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2018, Supplemental Data: Average Household Income, by Income Source and Income Group, 1979 to 2018.”

[20] Smith, Tori K, “2021 Index of Economic Freedom: After Three Years of Worsening Trade Freedom, Countries Should Recommit to Lowering Barriers.” The Heritage Foundation, November 12, 2020.

[21] Hayek, F.A., “Why I am Not a Conservative.” The Constitution of Liberty: The Definitive Edition, April 2011.

[22] Boudreaux, Donald J., “Unlike Oren Cass, F.A. Hayek Knew the Economics of Trade.” American Institute for Economic Research, February 20, 2020.

[23] Caldwell, Bruce, “The Publication History of The Road to Serfdom.” University of Chicago Press, 2007.

[24] Santana, Roy, “GATT 1947: How Stalin and the Marshall Plan helped to conclude the negotiations.” The World Trade Organization, 2017.

[25] Lighthizer, Robert, “Senate Committee on Finance Hearing on the President’s 2020 Trade Policy Agenda.” June 17, 2020, and Davis, Bob and Yuka Hayashi, “New Trade Representative Says U.S. Isn’t Ready to Lift China Tariffs.” The Wall Street Journal, March 28, 2021.

[26] “The Takeover of Hong Kong.” Reuters Special Report, 2020-2021; Jardine, Bradley, Edward Lemon, and Natalie Hall,“No Space Left to Run: China’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs.” Uyghur Human Rights Project and Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, 2021; and Ignatius, David, “Xi Jinping’s disturbing Maoist turn.” The Washington Post, September 21, 2021.

[27] Hull, Cordell. The Memoirs of Cordell Hull, Volume 1, 1948.

[28] Irwin, Douglas A., “Trade Liberalization: Cordell Hull and the Case for Optimism.” Council on Foreign Relations Working Paper, July 31, 2008.

[29] Krugman, Paul. Pop Internationalism, The MIT Press, February 1997, page ix.

[30] Riley, Bryan, “It’s Official: They’re Biden’s Tariffs Now.” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, October 5, 2021.