(pdf)

Introduction

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published a new explainer about its cost estimates, breaking out the information included in the various sections following a standardized format.[1]This laudable effort by the agency will help readers understand what the budgetary information means and why it is included in the estimates. This explainer is the latest step in CBO’s efforts to improve the transparency and accessibility of its work.

Last year, CBO revised the format it uses to publish cost estimates. The new revised standard layout does a better job of emphasizing areas of uncertainty in the cost estimates, pointing out the factors that could lead to budgetary outcomes that are different than CBO projected. The format could be further improved through consistent inclusion of current spending information, when applicable, so that the numbers featured in the budget tables have some context.

The Basics of Cost Estimates

As CBO’s new explainer notes, the primary purpose of CBO’s cost estimates is to provide information regarding the budgetary impact of legislation, including a breakdown of changes in discretionary spending, mandatory spending, and revenues. In general, CBO’s cost estimates show a ten-year window for mandatory spending and revenues. These figures are used by Congress for implementing rules and budget enforcement procedures. Discretionary spending is generally reported over a five-year period, as specified in the Congressional Budget Act of 1974. CBO’s reports may also indicate whether the proposal will have long-term budgetary consequences, and CBO is also required to report whether or not the legislation would impose an unfunded mandate on state governments, local governments, tribal governments, or private-sector entities.

Cost estimates also include a summary of the bill’s major provisions, a discussion of the estimated cost to the federal government, a review of the basis of the estimate including data sources and significant sources of uncertainty, pay-as-you-go information (where applicable), and, if necessary, a section comparing the current estimate with related previous versions during the same Congress. When there is not sufficient time to produce a detailed analysis before a pending hearing or vote, a cost estimate may only include the budgetary tables without the written analysis.

CBO reports that it takes two weeks on average to produce an estimate. The actual time per report depends on the complexity of the legislation, so there can be a wide range. Relatively simple estimates for legislation to reauthorize a program, for example, can be turned around on the same day that they were requested. More complex proposals can take several weeks, in cases where CBO needs to consult with stakeholders and experts, design a model, and acquire the needed data from either federal agencies or private-sector sources.

Boosting the Emphasis on Uncertainty

The explainer, and the new layout, show that CBO has improved its emphasis on the uncertainty involved in cost estimates. For complex scoring models where there are several interacting variables, CBO projects a range of possible outcomes. For enforcement purposes, CBO is required to produce a point estimate specifying yearly dollar amounts, so cost estimates reflect the middle of the distribution. There are also assumptions that CBO has to make during the process. Discussions of these matters have typically been tucked several pages deep in the cost estimate reports. The new layout includes a bullet point overview of the areas of significant uncertainty on the first page.

The big takeaway for most people when reviewing and discussing the potential costs of proposals is the dollar figure ultimately reported by CBO. But it is very important—especially for lawmakers drafting reforms or weighing the pros and cons of legislation—to consider alternate outcomes that could lead to significantly higher burdens on taxpayers.

The Best Way to Improve CBO’s Cost Estimates

As indicated in the explainer, CBO is required to report changes in spending and revenues are compared against a baseline. Unfortunately, this baseline can often be inaccurate due to constraints placed on the agency by Congress. Direct spending and revenues are reported relative to CBO’s 10-year baseline which generally reflects current law. However, many programs and tax breaks that are set to expire over some point during the 10-year window are typically extended. This happens frequently, for example, with many health care programs and the recurring tax extenders that are regularly reauthorized.[2]The current-law baseline also includes an expiration of many of the reductions and reforms included in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Similar tax cuts in the past were also extended.

This is also true for discretionary spending. The explainer notes, “The benchmark is based on current authorization law (under which many programs are not authorized beyond the current year) and thus differs from CBO’s 10-year baseline.” However, many of these programs continue to receive appropriations even though their authorizations have expired. CBO even produces an annual report of all the programs whose authorizations have already expired and also those whose authorization will soon expire. In theFebruary 2020 report, CBO identified “1,046 authorizations of appropriations that expired before the beginning of fiscal year 2020 that had not been overtaken by subsequent legislation. CBO estimates that $332 billion in appropriations for 2020 can be associated with 407 of those expired authorizations.”[3]

Because of this, the baseline tends to count on tax revenues that never materialize and it under-reports levels of spending given the record of policies that Congress tends to enact. While CBO is currently required by Congress to report a current law baseline, it can improve an understanding of the budget picture, and a more realistic portrait of deficits, by adding information on significant legislation indicating alternative fiscal scenarios. This would require new directives from Congress, and also potentially more staff and resources to perform additional projection work.

CBO’s cost estimates can also be improved by consistently including the current levels of spending for programs that are being extended, as well as the net level of spending projected to occur. This will make it far easier to determine the directional impact of legislation proposals. Whether a given bill increases or decreases spending relative to the previous fiscal year can be difficult to determine when reports only show spending relative to current law over the budget window.

The “basis of estimate” section will sometimes include a sentence indicating the current level of spending. For example, a bill from 2019, H.R. 1620, would reauthorize a grant program for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay program.[4]The table at the top of CBO’s estimate indicates that it will increase spending by $405 million from 2020 through 2024.[5]However, the text below the table clarifies that Congress provided $73 million, and a more detailed table below shows that annual spending on the program would rise to $93 million in 2024.

The estimates do not always include this valuable clarifying information. The cost estimate for H.R. 1585, the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act, reports that the proposal would increase discretionary spending by $4.1 billion through 2025, but does not indicate the current funding levels for the programs that are extended.[6]Advocates of the proposal have indicated that it would increase federal efforts against domestic violence, but the relative amount of that increase cannot be readily determined from the cost estimate.

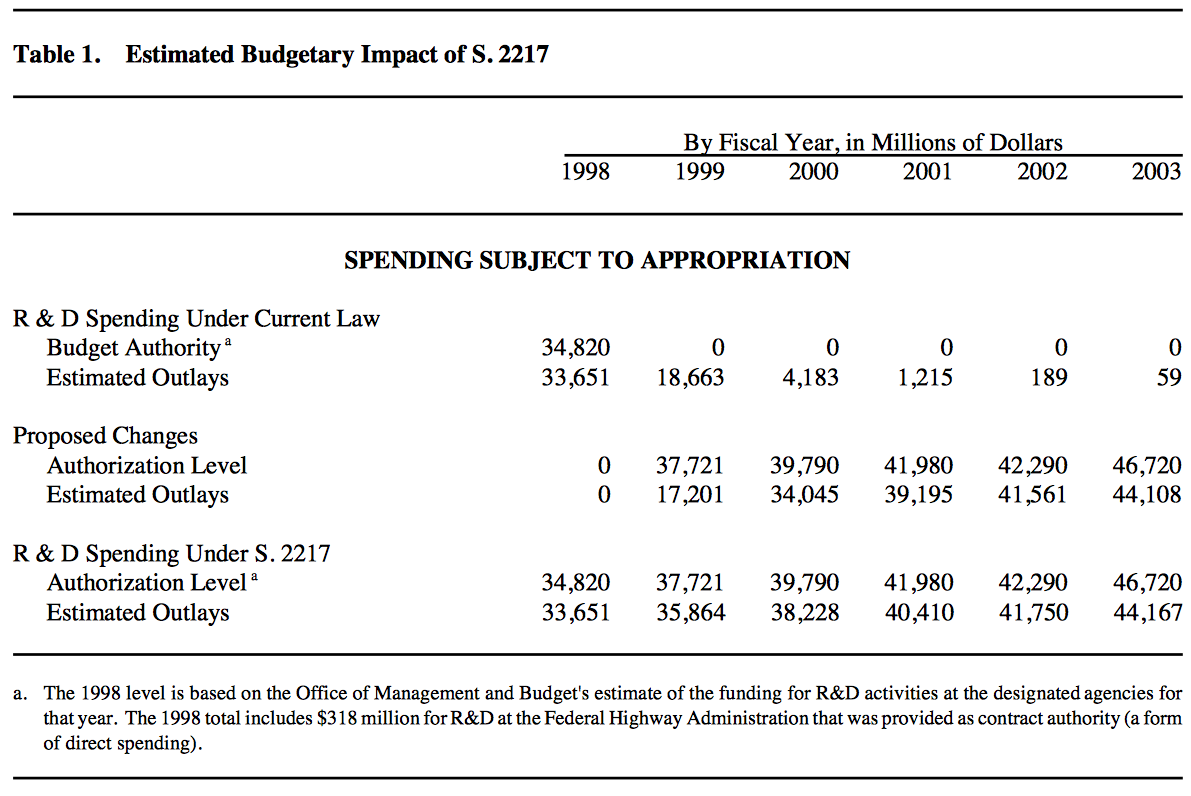

In fact, CBO’s reports previously included more of this information. For example, the following table is from a 1998 cost estimate for a bill to reauthorize federal research and development programs.[7]

It features an additional column showing the previous year’s spending level, an extra row at the top showing the spending under current law over the budget window, and an extra row at the bottom showing the net impact under the law. Relative to current law, the bill is boosting spending by $176 billion over five years, but when compared against current policy, it increases outlays by $2.1 billion annually.

Without this clarifying information, legislation that would reauthorize programs but at reduced levels would still look like net spending bills. Additional budgetary context would help clarify the net impact of proposals for lawmakers and taxpayers.

Conclusion

CBO’s cost estimates play an important role in the legislative process. The agency is to be applauded for the progress it has made in improving transparency and general understanding about not just its work products, but how it goes about producing cost estimates. By highlighting areas of uncertainty in the budget outlook, lawmakers can be forewarned about potential legislative impacts that could lead to deficits that are far worse than projected. Lawmakers, and taxpayers, could also be better informed about the budgetary impact of legislation by appending additional information about a current policy baseline.

[1]Congressional Budget Office, “CBO’s Cost Estimates Explained,” February 2020.

[2]McDermott+Consulting, “Healthcare Extenders: What’s on the Table for 2019,” October 11, 2019. Brady, Demian and Plott, Jacob, “How ‘Legislating to the Score; Makes Tax Policy Worse,” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, August 22, 2019.

[3]Congressional Budget Office, “Expired and Expiring Authorizations of Appropriations: Fiscal Year 2020,” February 5, 2020.

[4]H.R.1620 - Chesapeake Bay Program Reauthorization Act, September 19, 2019.

[5]Congressional Budget Office, “Cost Estimate: H.R. 1620, Chesapeake Bay Program Reauthorization Act,” October 2, 2019.

[6]Congressional Budget Office, “Cost Estimate: H.R. 1585, Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019,” June 21, 2019.

[7]Congressional Budget Office, “Cost Estimate: S. 2217, Federal Research Investment Act,” September 10, 1998.